The ideas of France’s philosophers, the refinement of its language, and the sumptuousness of its fashion defined the eighteenth century. French paintings from the Age of Enlightenment gleam from the walls of great museums from St. Petersburg to New York. What would the Wallace Collection be without Watteau, the Frick without Fragonard? Yet sculpture contributed as much to this era as France’s other arts. Certainly there are well-known examples around the world—Jean- Antoine Houdon’s statue of George Washington in Richmond, for example, or Étienne-Maurice Falconet’s equestrian monument to Peter the Great on the Neva. But the full richness of eighteenth-century French sculpture—as spirited as it was virtuoso—has been little noted outside its homeland.

All the more reason to celebrate the decision of the Liebieghaus in Frankfurt, in collaboration with the Musée Fabre in Montpellier, to gather together a glittering selection of French sculpture from the days of Voltaire to the First Empire. The show includes both statues and smaller works—among them, above all, a remarkable ensemble of portrait busts. The Liebieghaus galleries are not large and do not always offer enough space for the works to achieve the full effect of their magic and wit. Nevertheless, what an experience! It feels like entering a Paris salon in the days of Madame du Deffand and eavesdropping on the philosophes in brilliant conversation.

The high point of this exhibition of about forty works is the work of Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741–1828), the last and probably greatest French sculptor of the eighteenth century. In his work, we can witness a full liberation from the panegyric rhetoric of the baroque. Between 1764 (the year Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s History of Ancient Art gave educated Europe a new perspective on the legacy of classical antiquity) and 1768, the young Houdon studied at the French Academy in Rome. The flounces and wigs of the rococo were fast disappearing. There is no other artist to whom Diderot’s famous remark applies so well: “To learn to see nature we must study antiquity.”

The long line of French artists who were shaped by a theorizing approach to their craft—a line that begins with Poussin and to which a sculptor like Falconet still belonged—ends with Houdon. His was a natural genius, combining an empirical intelligence with a sixth sense for materials and physiognomies. While often brilliant, his works possess an unadorned naturalism that avoids both fashionable flourishes and the lachrymose sentimentality of contemporaries like Jean-Baptiste Greuze and Samuel Richardson. One is tempted to call him the physiocrat among the sculptors.

For the library of a wealthy royal counselor’s town house in the fashionable Faubourg Saint-Honoré, Houdon created two statues personifying Summer and Winter. The seasons were still a popular motif for eighteenth-century painters, sculptors, writers, and composers—one that gained erotic charge in France during the time of the Marquise de Pompadour. Yet here that motif was as good as reinvented by Houdon.

In his enchanting depiction of Summer, the Ceres of antiquity is transformed into a lovely gardener. A wreath of flowers and wheat adorns her hair. In her right hand she carries a sickle, a sheaf of grain, and poppies; in her left a prosaic watering can. Instead of neoclassical personification, Houdon gives us a slice of nature. The charming face of the young woman resembles the artist’s new bride, Marie-Ange Cécile Langlois.

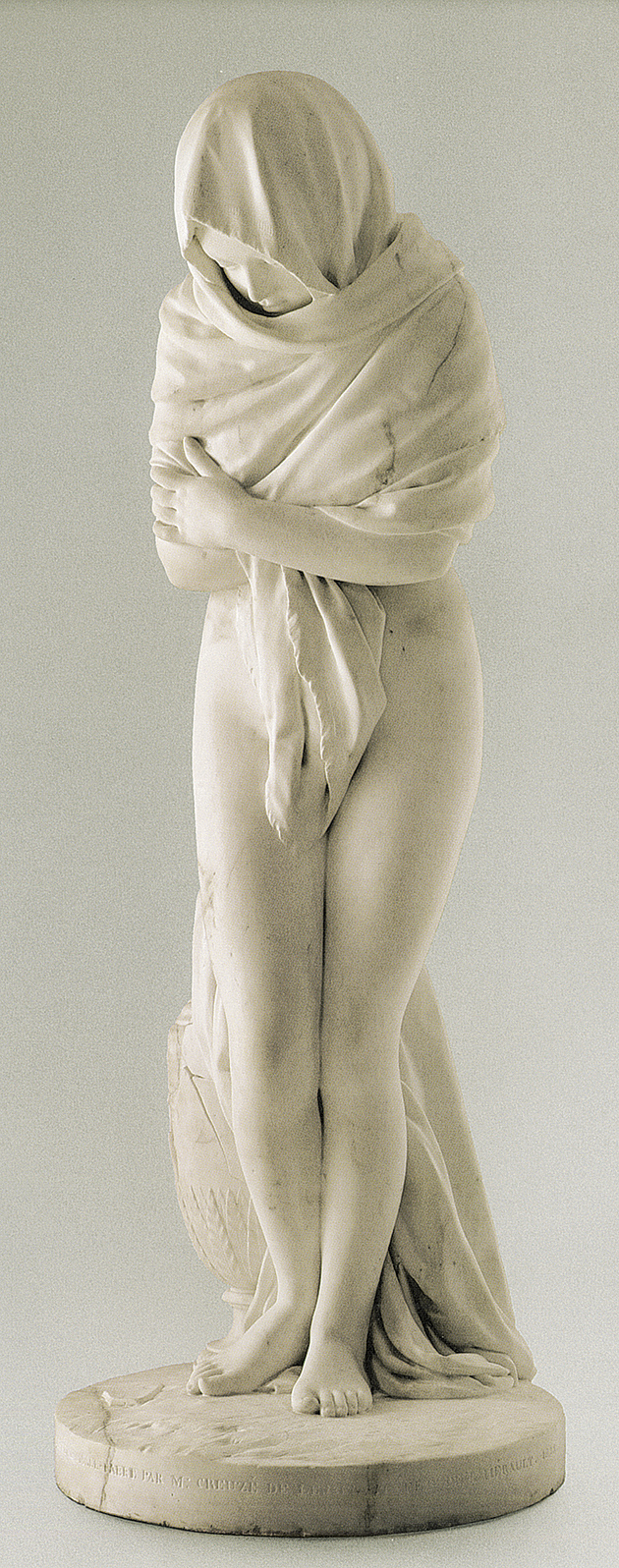

Houdon did not portray all four seasons, just Summer and Winter; his challenge was to contrast warmth and cold, flowers and frost. Ceres transformed into a gardener is followed by Venus shivering in the winter cold. Her lovely young body—is it Marie-Ange Cécile once again?—is unclothed except for the wrap thrown over her head and shoulders. On the ground at her feet is a cracked vase whose exterior is covered with spilled water, turned to ice. Perhaps the exhibition catalog is overly learned in its discussion of this bewitching statue. Shivering figures are included in images of winter since antiquity, and Houdon’s statue evokes a phrase that goes back to Terence: “Venus freezes without Ceres and Bacchus.” Mademoiselle Winter is not mourning her lost innocence, she’s just cold! (See illustration on page 60.)

Houdon’s statue of Diana, goddess of the moon and the hunt, is even more celebrated. Completely nude, she holds a bow and arrow in her lowered hands and turns her head to look at something as she hurries on her way. The naked huntress Diana had long been a popular subject in France—one recalls the portrait of Henri II’s mistress Diane de Poitiers in the Château d’Anet—and Houdon adheres to Winckelmann’s description of the antique Diana. The accuracy of his rendering of this flawless body extends even to the precise modeling of the vulva. The guardians of morality were outraged, but they were missing the witty point of this singular statue: Diana, whose charms are portrayed in such detail here, is the chaste goddess. With the purity of this work, Houdon wrested the sublime beauty of the female body from the erotic voyeurism of Boucher or Fragonard.

Advertisement

Yet it is with the portrait busts that the show attains its distinctive character. Houdon’s works are surrounded by an array of them by other sculptors—Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne (who belonged to the preceding generation), Augustin Pajou, Jean-Jacques Caffieri, and above all Jean-Baptiste Pigalle. Although there are impressive portraits among them, only Pigalle’s bust of the aging yet still vigorous Diderot (1777) can hold its ground with the busts by Houdon, who surpasses all his predecessors and contemporaries in his technical mastery, as well as in his genius for character. Houdon was the first sculptor to grant each sitter the right of man to his own physiognomy.

The early bust of a peasant girl from Frascati, fashioned while he was still in Italy, already possesses a purity that completely eschews the pomp of upper-class portraiture. It combines Winckelmann’s feel for antiquity with an unspoiled naturalness reminiscent of Rousseau. Still, only after he returned to France did Houdon begin creating the portraits that make him the incomparable iconographer of the Enlightenment.

His bust of Christoph Willibald Gluck is physiognomic thunder and lightning, unsparingly displaying the choleric, pockmarked face of the composer who had taken Paris by storm. No one had ever seen such a work. It casts aside all etiquette to show the new face of genius, an echo of the article on génie in Diderot’s Encyclopédie.

In his bust of the great naturalist Comte de Buffon, an intellectual flame shines through the aristocratic pose, bestowing upon the sitter the radiance of a free human being. Just as individualized is the bust of the mathematician Condorcet, another aristocrat, whom Houdon portrays as withdrawn and almost shy. French literature has a rich tradition of character description from Montaigne through the moralistes to Saint-Simon. Houdon translates the high intelligence of this art of characterization into marble, bronze, terracotta, and plaster.

Sometimes one gets the impression that the sculptor almost forced himself onto famous contemporaries in order to benefit (both artistically and financially) from their renown. When the eighty-four-year-old Voltaire returned to Paris in 1778 after many decades of exile in Switzerland, Houdon immediately chiseled his bust and then made many copies of the work. It is also there in the exhibition: a marble likeness without a wig. All the signs of age—teeth gone, eyes sunken in their sockets—are assiduously displayed; the natural decrepitude of man is not denied. Yet the unflagging agility of Voltaire’s esprit and his fierce irony speak with unbroken vitality from the ruined face. He smiles and his eyes seem to sparkle with an inner fire—an effect of which Houdon was a master.

After Voltaire’s death, Houdon sculpted a large marble statue of him. It shows the famous philosopher seated in a chair and wrapped in something that could be a dressing gown or some sort of imaginary costume from classical antiquity. Voltaire sits in state, but not on a royal throne. Instead, he occupies the philosopher’s armchair, laughing at the foolishness of the world like a new Democritus. The show includes a small terra-cotta version of this statue, which is more congenial and cheerful than the larger work in marble.

Houdon lived well into the nineteenth century, an artistic holdover from the Age of Enlightenment. In 1806 Napoleon, having recently given himself the title of emperor, sat for the aging sculptor. (See illustration on page 58.) In its veracity and grace, the resulting bust outshines all other portraits of Napoleon, yet this unpretentious and humane likeness is said not to have pleased the ruler. The eyes seem to be mirrors of all his dreams. Even in the art of portraiture, truth and power seldom get along with each other.

This Issue

April 8, 2010