For literature, perhaps the most precious dividend from the collapse of the Soviet system has been the discovery of previously censored or unknown manuscripts by the great writer Andrey Platonov. Joseph Brodsky put him on a par with Joyce, Musil, and Kafka. Yet in his own lifetime in Russia he was published only intermittently, and then usually subjected to the fiercest criticism by the literary authorities, including Stalin, while many of his most important works, such as his long novel Chevengur (1929) and his masterpiece The Foundation Pit (1930), remained unpublished until the relaxation of censorship in the glasnost period of the late 1980s.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, there has been a steady flow of new Platonov texts: the unfinished novel Happy Moscow came out in 1991; a complete version of The Foundation Pit appeared in 1994 (earlier editions had been cut and bowdlerized); the complete text of the long story “Dzhan” (“Soul”), which had been published in a censored form in the 1960s, appeared only in 1999.1 Letters, notebooks, unfinished stories, and texts that were written by Platonov “for the drawer” continue to appear in literary journals in Russia.

It is from these Russian publications that Robert Chandler and his wife Elizabeth have produced their many translations, including these two latest publications by New York Review Books, in which they have brilliantly dealt with the challenges of rendering into readable English the extraordinary quality of Platonov’s prose. As Brodsky wrote, it is precisely Platonov’s use of language that makes him such a revolutionary writer, and one so dangerous to the Soviet regime, “because he attacks the very carrier of millenarian sensibility in Russian society: the language itself.”2

1.

To get readers immediately acquainted with Platonov’s unique style, this is how he sounds in the opening lines of The Foundation Pit in the Chandlers’ translation:

On the day of the thirtieth anniversary of his private life, Voshchev was made redundant from the small machine factory where he obtained the means for his own existence. His dismissal notice stated that he was being removed from production on account of weakening strength in him and thoughtfulness amid the general tempo of labor.

The Foundation Pit is a dystopian work—a distorted mirror image of the Soviet “production novel” of the 1920s and 1930s—but it would be wrong to see Platonov as an anti-Soviet writer or a satirist. Born in 1899, he came of age with the revolution of October 1917, and remained a true believer in the Soviet system, despite his many doubts about Stalin’s murderous policies.

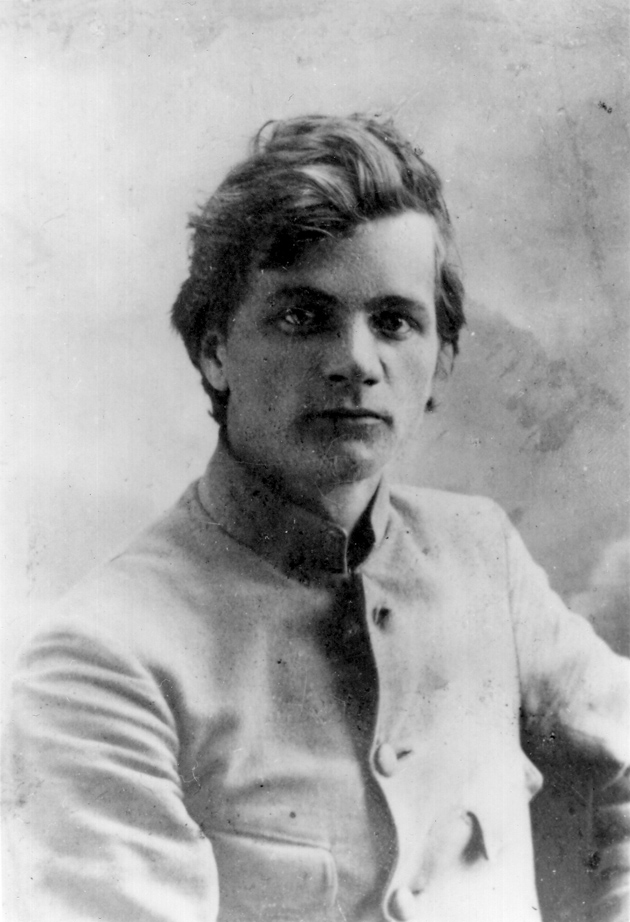

Platonov was the pen name of Andrey Platonovich Klimentov. His father was a metal worker for the railway in an industrial suburb of Voronezh, a place between the city and the open countryside some two hundred miles south of Moscow, and the tension between the old world of the peasant village and the new world of Soviet industry features prominently in Platonov’s work. He loved machines, was able to describe them in great technical detail, and, like all Marxists, he believed in them as the “locomotives of history.” Platonov associated communism with movement. The train passing through a rural wilderness—the sound of a radio in the engine room or the image of its newspaper-reading passengers offering a glimpse of the future to some lonely peasant by the railway track—is a recurring symbol in his prose.

During the Civil War (between 1918 and 1921) Platonov worked on the railways, helping to supply the Red Army. He then served as a rifleman in a special detachment that was probably engaged in the forced requisitioning of grain from the peasantry. As a result of that requisitioning, over a million peasants in Voronezh and the Volga provinces died from starvation and its attendant diseases when drought destroyed the harvest of 1921. Platonov was already writing by this stage—he was an active member of the Union of Proletarian Writers—but he gave it up to work as an engineer, planning and constructing hydroelectric and peat-fired power stations to help the peasants irrigate their drought-stricken land. In his autobiographical story “The Motherland of Electricity” (1939), included in Soul, he recounts one such episode. The story reflects Platonov’s confidence in the transforming power of technology but also his awareness of the fragility of the people whose lives it transforms.

For the next three years, Platonov worked as a land reclamation engineer in Voronezh province. He supervised the digging of 763 ponds and 331 wells, as well as the draining of 2,400 acres of swampland. After a brief spell in Tambov, in a neighboring province, he gave up land reclamation work and returned to Moscow to become a full-time writer, winning the approval of Maxim Gorky for his first collection of stories, The Epifan Locks (1927). In these, and even more in Chevengur, we feel Platonov’s growing doubts about the ability of the great utopian projects of the Soviet system to transform nature (including human nature) without first destroying it—doubts that would lead to his intellectual break with the Stalinist regime in The Foundation Pit.

Advertisement

In The Epifan Locks, a timely allegory on Peter the Great’s grandiose scheme to link the Don and Oka rivers with a waterway, thousands of peasant laborers are killed in building a canal that cannot be used because the supply of water in the surrounding steppes is too meager. (The White Sea Canal, Stalin’s great construction project of the early 1930s using Gulag labor, turned out to be similarly disastrous, with tens of thousands killed to dig a waterway whose economic use was limited because it was too shallow for all but small barges and passenger vessels.)

In Chevengur, Sasha Dvanov, an orphan from a town struck by the famine, goes in search of “true socialism.” On his way he teams up with the quixotic revolutionary Kopenkin, knight-errant of Rosa Luxemburg, who rides a horse called “Proletarian Strength.” The two men end up in a remote town called Chevengur, where they have been told that communism has arrived. The town is in the hands of a group of Bolsheviks who have set up their soviet in a former church. No one knows what “communism” is: the collected works of Marx cannot tell them; propaganda posters cannot picture it; yet everyone believes in it with the fervor of a new religion.

The Soviet leaders have a naive faith in the magical power of the word itself to change the world. One thinks the planet will become brighter and more visible from the moon once communism has arrived. In the belief that it is only necessary to destroy the old society for the utopia to appear, the Bolsheviks of Chevengur proceed to kill the bourgeoisie, and then to wipe out the petite bourgeoisie to make sure the job is done, though all this killing makes them no more certain of the meaning of their goal. Believing they have reached their utopia, they declare the end of history, abolish labor, and wait for communism to provide for them. But it does not. A hungry winter approaches, and the town is invaded by the Cossacks. Kopenkin is killed in the battle, and Dvanov rides off to commit suicide.

2.

The same bleak disillusionment gives structure to The Foundation Pit. The novel starts with another wanderer, the thirty-year-old Voshchev, who has been laid off by his factory because he thinks too much. Voshchev (like Platonov) is a truth-seeker who lives on the margins of society because he is unable to find a place in it or a meaning for his existence. “Stay here,” he tells a fallen leaf, “and I’ll find out what you lived and perished for. Since no one needs you and you lie about amidst the whole world, then I shall store and remember you.” As Robert Chandler and Olga Meerson point out in their afterword, Voshchev, in effect, is giving an address that Platonov makes to his own characters, “all of whom seem equally superfluous in the world.”

Voshchev wanders to the edge of town and settles down in “a warm pit for the night,” only to be woken by a mower, who tells him it’s a building site, the foundation pit for a vast communal home in which all the workers of the town will live. Voshchev joins the team of workers, and they dig, but no building is ever built. For Prushevsky, the director of works, what they are building is the socialist dream:

After ten or twenty years, another engineer would construct a tower in the middle of the world, and the laborers of the entire terrestrial globe would be settled there for a happy eternity.

For Safronov, a Bolshevik ideologue who speaks in Soviet bureaucratese, the real building site is the human soul:

And this is why we must throw everyone into the brine of socialism, so that the hide of capitalism will peel away and the heart will attend to the heat of life around the blazing bonfire of the class struggle and enthusiasm will originate!

For Zhachev, a legless veteran of the Civil War, all that really matters is the “class struggle” involved in the digging of the pit—a hole in which to bury all the “parasites” of the old society.

One day, a peasant arrives at the site looking for coffins that had been stored there to be given back to his village. Voshchev follows the peasant and his train of coffins and finds a village that is being turned into a collective farm—a nationwide process of forced collectivization that involved what Stalin termed the “liquidation of the kulaks as a class” and the expropriation of all their property in a murderous campaign, a social holocaust, in which ten million “kulaks” (the so-called “rich” or “capitalist peasants”) and their families were, between 1929 and 1932, expelled from their homes and sent to labor camps or remote Siberian penal settlements, where many of them died. The rest of The Foundation Pit takes place in this cauldron of class hatred and violence unleashed by the Bolsheviks against the peasantry.

Advertisement

Unlike other writers, who were shown model collective farms on trips arranged by Stalin’s political police, Platonov knew what was being done in the name of collectivization. He was sent by the Commissariat of Agriculture to report on the new collective farms. His notebooks leave no doubt that what he saw shook him to the core. This is what he wrote on a journey to the Volga and northern Caucasus in August 1931:

State Farm no. 22 “The Swineherd.” Building work—25 percent of the plan has been carried out. There are no nails, iron, timber…milkmaids have been running away, men have been sent after them on horseback and the women have been forced to work. This has led to cases of suicide…. Loss of livestock—89–90 percent.

The peasants slaughtered their own livestock to prevent them from being confiscated by the Soviet authorities for the collective farms.

These journeys served as the inspiration for a whole series of works by Platonov devoted to the themes of collectivization and the terror-famine of 1932–1933. None was published in Platonov’s lifetime except “For Future Use” (1931)—a story heavily criticized by Stalin as a “kulak chronicle.” Like The Foundation Pit, all these stories have an unreal air, though according to Chandler and Meerson, referring to the unpublished work of the Russian literary scholar Natalya Duzhina, they “contain barely an incident or passage of dialogue that does not directly relate to some real event or publication from these years.”

Perhaps this surreal atmosphere was necessary to write about events so terrible “as to be beyond the comprehension of anyone except a madman,” as Robert Chandler has eloquently commented elsewhere.3 As Boris Pasternak recalls of his own visits to the new collective farms to collect material for a book:

Words do not have the power to express what I saw. It was such an inhuman, unimaginable calamity, such a terrible disaster that it became—if one can say such a thing—abstract and beyond rational apprehension.4

But Platonov’s surrealism is also integral to his attack on the “millenarian sensibility” at the core of this violence. By infusing his prose and the discourse of his characters with the linguistic deformations and abstractions of official Sovietspeak, Platonov creates a fantastic world where words are alienated from reality, where abstract slogans like “the liquidation of the kulaks as a class” have a terrifying power to summon all those Safronovs and Zhachevs who have taught themselves to think and speak in these official terms to a war against “kulaks.” The destructive power of these slogans lies precisely in the fact that they are abstract: they do not talk of “kulaks” as “people” and thus they relieve their executioners of the debilitating moral burden of thinking of their victims as individual human beings. In the Soviet Union there were millions of Safronovs and Zhachevs in real life.

Because of this complex interplay with the changing Russian language of the early Soviet years, The Foundation Pit is a minefield for the translator. In his introduction to The Portable Platonov, a compilation of extracts from his works, Robert Chandler writes:

The ideal translator of Platonov would be perfectly bilingual and have an encylopaedic knowledge of Stalin’s Russia. He would be able to detect deeply buried allusions not only to the classics of Russian and European literature, but also to speeches by Stalin, to articles by such varied figures as Bertrand Russell and Lunacharsky (the first Bolshevik commissar for Education), to copies of Pravda from the thirties and to long-forgotten minor works of Socialist Realism. He would be a gifted and subtle punster. Most important of all, his ear for English speech-patterns would be so perfect that he could maintain the illusion of a speaking voice, or voices, even while the narrator or the individual characters are using extraordinary language or expressing extraordinary thoughts.

The Chandlers do not pass all these tests (no one could) and there are places in their translations where the subtle intonations and rhythms of the Russian are inevitably lost, but the complex allusions and borrowings are explained in the scholarly footnotes, and overall it is hard to see how we could get a better English version of Platonov’s prose—nor one more likely to win him the readers he deserves. Here is what his prose sounds like in one of the most poetic and haunting moments of The Foundation Pit, when the legless Zhachev, having witnessed the expulsion of the “kulaks,” watches as they sail downriver in a raft toward the open sea:

Liquidating the kulaks into the distance brought Zhachev no calm; he even felt worse, though it was not clear why. For a long time he observed how the raft floated systematically down the snowy flowing river and the evening wind ruffled the dark dead water pouring, amid chilled farmlands, into its own remote abyss—and in his heart it was getting melancholy and boring. Socialism, after all, had no need for a stratum of sad freaks, and he too would soon be liquidated into the distant silence.

The kulak class on the raft was all looking in one direction—at Zhachev; these people wanted to take note of their birthplace forever, together with the last happy man there.

By then the kulak river transport had begun to disappear around a bend, behind the bushes on the bank, and Zhachev was losing the appearance of the class enemy.

“Fa-are we-ell, parasites!” Zhachev shouted down the river.

“Far-are we-ell!” responded the kulaks sailing off to the sea.

3.

From the middle of the 1930s there was a change in Platonov’s prose. There were no more great, experimental works in the mold of Chevengur or The Foundation Pit. Under pressure from the literary authorities, Platonov began to write in a more conventional style, securing for himself a place on the fringes of the Socialist Realist mainstream, where he might get his work published. Many of his stories in this period, beginning with “Soul” in 1935, have a lyrical and sometimes even sentimental quality. There are beautiful descriptions of nature, landscapes, plants, and animals, and stories based on family and romantic relationships.

It would be misleading to represent this return to the classical tradition as an artistic compromise, though no doubt Platonov wanted sincerely to become accepted as a “Soviet writer” and even wrote to Gorky in 1933 to ask how he could overcome the ban on the publication of his work after Stalin’s criticisms of “For Future Use.” Platonov’s change of theme, his decision to write more simply, in more human terms and with more hope, was rather his attempt to find a way out of the abyss of The Foundation Pit. The recurring theme in all these later stories is the capacity of human beings to save themselves through love and comradeship.

“Soul” (“Dzhan”) has its origins in a trip Platonov made with a brigade of writers to Central Asia in 1934. The visit was arranged by Gorky with the aim of publishing a collective work to celebrate ten years of Soviet Turkmenistan. Platonov had applied to join the notorious Writers’ Brigade established by Gorky and to be sent by the political police to report on the building of the White Sea Canal in 1933, but his application was turned down, so his inclusion on this trip was a turning point for him.

The plot of “Soul” fits into the mold of the Socialist Realist literature of the Stalinist era: an economist called Nazar Chagataev is sent from Moscow to his birthplace in the Amu-Darya basin to save his people—a lost nomadic tribe in the desert. But the real subject of the story is the fragility of this people’s ancient way of life—a culture that was destined to be left behind by the “locomotive of history.” Toward the end of the story, when the tribe has broken up to work in Russian towns and “wherever there was money to be earned,” Chagataev leaves for Moscow with a little girl, whom he plans to educate. On their way, they stop in the foothills of the Ust-Yurt mountains, where he asks an old Turkmen which tribe he is from:

“We’re Dzhan,” replied the old man, and it emerged from his words that every little tribe, every family and chance group of gradually dying people living in the empty places of the desert, the Amu-Darya and the Ust-Yurt, called themselves by the same name: Dzhan. It was their shared name, given to them long ago by the rich beys, because dzhan means soul and these poor, dying men had nothing they could call their own but their souls, that is, the ability to feel and suffer.

Platonov’s stories speak for the forgotten poor, railway workers, peasants, uprooted soldiers, nearly all of them weak or broken people with nothing but their soul and perhaps a family to call their own, and all living on the edge of Stalinist society.

In 1938, Platonov’s fifteen-year-old son was arrested on trumped-up charges of belonging to a student terrorist organization and sent to the Gulag. He returned in 1942, already dying from the tuberculosis that killed him in January 1943. Platonov’s grief is felt on every page of these stories, nowhere more so than in “The Cow” (1938 or 1939), where the dumb animal stands for every grieving mother in the Soviet Union, a country where people did not speak about the missing and the dead:

The cow was not eating anything now; she was breathing slowly and silently, and a heavy, difficult grief languished inside her, one that could have no end and could only grow because, unlike a human being, she was unable to allay this grief inside her with words, consciousness, a friend or any other distraction…. She only needed one thing—her son, the calf—and nothing could replace him: neither a human being, nor grass, nor the sun.

In one of his last and finest stories, “The Return” (1946), Platonov leaves us with a moving reminder that the love of children can heal anything. A soldier called Ivanov returns from the war to find that life has moved on without him. He feels excluded from his own family, betrayed by his wife, and supplanted by his boy, who has taken on the responsibility for running the household and caring for his small sister. The soldier leaves, intending to find a girl he had met and flirted with on his way home. But as his train pulls away from the station, he sees two children running after it, and recognizes that they are his own:

Ivanov threw his kit bag out of the carriage onto the ground, and then climbed down to the bottom of the step and got off the train, onto the sandy path along which the children were running after him.

“The Return” was fiercely criticized. It lacked the optimistic tone that was obligatory in all art forms following the Soviet victory of 1945. Platonov was unable to publish any more work during his lifetime. He spent his final years in poverty, living with his wife and five dependents in a two-room flat belonging to the Writers’ Union in Moscow, allowed only occasional ghost-written work, such as editing fairy tales for children. The tuberculosis he had contracted from his son would not let him work much in any case. He died from it in 1951.

This Issue

April 29, 2010

-

1

Andrei Platonov, Proza (Moscow: Slovo, 1999).

↩ -

2

Joseph Brodsky, “Catastrophes in the Air,” in Less Than One: Selected Essays (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1986), p. 283.

↩ -

3

See Robert Chandler’s introduction to Andrey Platonov, The Foundation Pit, translated by Robert Chandler and Geoffrey Smith (London: Harvill, 1996), p. xi.

↩ -

4

Cited in Chandler’s introduction to the 1996 edition of The Foundation Pit, p. xi.

↩