The recent passage of health care reform was certainly historic—it is the largest piece of progressive domestic legislation to become law in forty-five years (since Medicare). After many desultory and dispiriting months, President Obama can now plausibly say that “that hopey-changey thing,” as Sarah Palin mockingly referred to his grand campaign theme in a February 2010 speech, is well underway.

But to what degree will the victory change political dynamics in the capital? Here, the potential impact of the victory probably can’t match the historical importance of the accomplishment. Just as liberal despair in recent months was shortsighted and overwrought, the liberal euphoria that came with the bill’s passage is similarly worth examining, for three reasons.

First, the passage of the bill into law marks a beginning rather than an end. The law’s most conspicuous elements—the creation of health insurance exchanges, the subsidies for coverage, the full range of new regulations governing insurance companies—won’t take effect until 2014. Even then, myriad complex questions of implementation will need sorting out.

The most important of these will surround the structure of and rules governing the new exchanges the bill will set up so that small businesses and individuals can purchase coverage at competitive prices. Whether the exchanges really work will depend, for example, on the success of “risk adjustment” policies, so that the plans offered in the exchanges won’t vary too greatly in what they charge and offer consumers. This is why many liberals would have preferred one national exchange rather than state or regional exchanges—the users of one national exchange, with its much larger risk pool, would have far more power to negotiate costs with insurers.

There will be dozens of such questions to be answered by future bureaucrats, and inevitably, there will be misjudgments and unforeseen difficulties. Ferocious political opposition will continue. Not much mentioned during the debates over the bill—although clearly a source of opposition to it—was the fact that it will add to the Medicaid rolls an estimated 16 million relatively poor people, many of them black or Latino. This is a change that will be criticized by some state governments, which administer Medicaid jointly with the federal government. But there will also be future disagreements over implementation within the group of people who want to make the law work. The passage of this bill merely starts a policy debate that will continue for years.

Second, there is the matter of the political consequences of this bill—and the way it was passed—for other Democratic initiatives. It is natural to think that a crucial legislative victory will embolden the winners to push ever onward, aiming their mighty sword at fresh targets. Progressives will certainly hope that this will be the case—with regard to, say, financial reform, or climate change legislation, or immigration reform.

But in this instance there are probably more reasons to think the opposite will be the case. This battle was so fierce that legislators, an extremely cautious class by nature, will be loath to step into another fight like it. Their vocal right-wing constituents, their many thousands of dollars in contributions from powerful lobbies, and the constant Democratic fear of being seen as too liberal will likely combine to persuade most legislators that climate change legislation, for example, can wait a while.

There is one possible exception to this, and it’s an important one. Congress seems poised to tackle financial reform this year. The House passed its version of a reform bill last December, and another version is now moving through the Senate, with an outcome expected in perhaps two months’ time. This is one case in which the health care victory does seem to have reverberated to the Democrats’ benefit, at least for the time being. The day after the House of Representatives passed the health bill, the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs passed chairman Christopher Dodd’s financial reform package.

The bill passed the committee on a straight party-line vote of 13–10, but in the following days, a couple of crucial Republicans indicated that they wanted to cooperate with Dodd on passing a bill. Part of this has to do with reassessments by some Republicans about their obstinacy over health care (especially since they lost). And part of it reflects a belief that while health care reform was not popular, new financial regulations are. Senator Bob Corker of Tennessee said, “I don’t think people realize that this is an issue that almost every American wants to see passed. There’ll be a lot of pressure on every senator and every House member to pass financial regulation.”1

Advertisement

Of course, Republican participation will water down the bill. And liberal critics already disparage it as very weak tea—most importantly, because the new consumer financial protection agency would be lodged within the Federal Reserve rather than created as an independent entity. Nevertheless, a victory including a couple of Republican votes would have its own importance and would signal the emergence of a hole or two in the Republican unified front.

That front remains a third reason for circumspection. Even if the administration peels off a Republican or two on the finance issue, there seems little doubt that the partisan pyrotechnics will continue unabated on most matters. The actions of Republicans and their supporters during the House health care debate and right after passage were astonishing; more astonishing still was the attempt by the Virginia Republican Representative Eric Cantor to blame Democrats for “fanning the flames of violence” because they confirmed to the press reports of violence against them. (Cantor also referred to a bullet that came through a window in his district office, but the Richmond police categorized that as a “random” act—probably a bullet fired into the air from some distance, with no political overtones.)

The GOP was determined to make health care Obama’s “Waterloo,” as Republican Senator Jim DeMint put it last year. That failed; but such reflections as those of Bob Corker are rare. Here is what Mitt Romney—who as governor of Massachusetts signed into a law a health care bill that is quite similar in spirit and letter to the one Obama has signed, and that, despite budget problems, is working out rather well so far—had to say about the House’s March 21 vote:

America has just witnessed an unconscionable abuse of power. President Obama has betrayed his oath to the nation—rather than bringing us together, ushering in a new kind of politics, and rising above raw partisanship, he has succumbed to the lowest denominator of incumbent power: justifying the means by extolling the ends. He promised better; we deserved better.

He calls his accomplishment “historic”—in this he is correct, although not for the reason he intends. Rather, it is an historic usurpation of the legislative process—he unleashed the nuclear option, enlisted not a single Republican vote in either chamber, bribed reluctant members of his own party, paid-off his union backers, scapegoated insurers, and justified his act with patently fraudulent accounting. What Barack Obama has ushered into the American political landscape is not good for our country; in the words of an ancient maxim, “what starts twisted, ends twisted.”

His health-care bill is unhealthy for America. It raises taxes, slashes the more private side of Medicare, installs price controls, and puts a new federal bureaucracy in charge of health care. It will create a new entitlement even as the ones we already have are bankrupt. For these reasons and more, the act should be repealed. That campaign begins today.

By the end of that week, Palin, campaigning for John McCain, affirmed that the Republicans were not merely the party of no: “We’re the party of hell no!”

Beyond the rhetoric, we have the lawsuit filed by thirteen attorneys general (twelve Republicans plus a Democrat from Louisiana) arguing that health care reform is unconstitutional because mandating the purchase of insurance by individuals violates the Constitution’s commerce clause. Most legal scholars think this is far-fetched.2 With the Roberts court, one can never be completely sure, but it seems safe to say that for at least some of these attorneys general, the lawsuit is inspired by state politics—Florida Attorney General Bill McCollum, for example, is running for governor.

The health care victory is very much worth savoring. But it will not by itself change the toxic culture in Washington. That won’t happen unless the voters punish the Republicans in another election or two, and that prospect at this point is far from clear.

—April 1, 2010

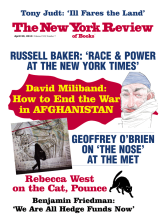

This Issue

April 29, 2010

-

1

See Victoria McGrane and Lisa Lerer, “Republican Senators: Regulatory Reform Will Pass,” Politico, March 25, 2010.

↩ -

2

See an especially perceptive paper by Simon Lazarus, “Mandatory Health Insurance: Is It Constitutional?,” December 2009, written for the American Constitution Society, which is the liberal counterpart to the Federalist Society. Lazarus reviews the relevant precedents going back to 1944 that support congressional regulatory authority under the commerce clause.

↩