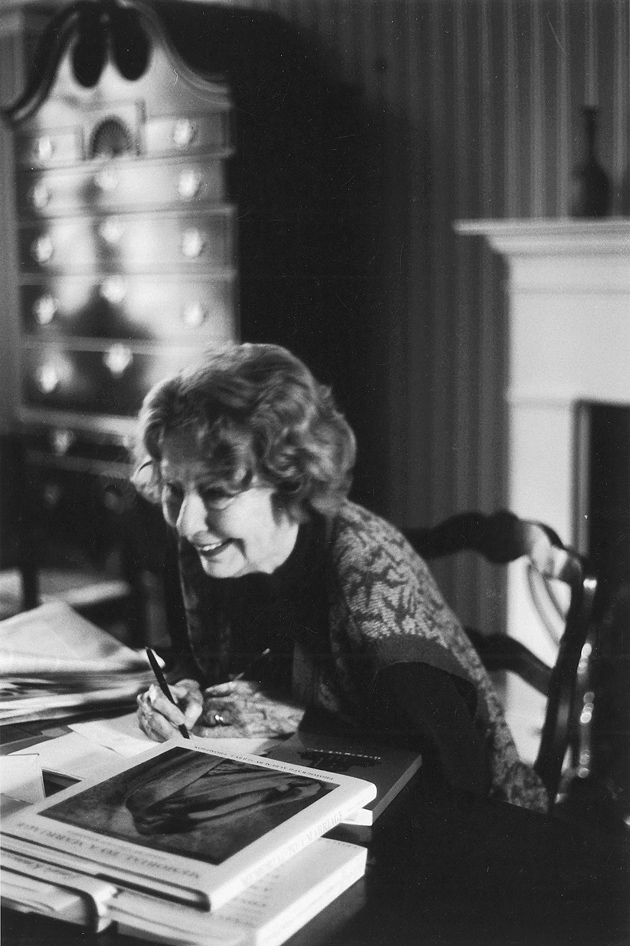

Elizabeth Hardwick, born in Lexington, Kentucky, in 1916, said that if she had to come from the South, she didn’t mind it being the Upper South, because even though a lot of nonsense about the Confederacy could be found in Kentucky as readily as anywhere else, for some reason when she was growing up, coming from a border state made her feel less complicit as a white person in the racial order all around her. She said she was probably as terrified as a black Northerner when in the Deep South, afraid that other white people might read her mind and discover her scorn for the exculpatory stories they in cotton country told themselves. She said that as distressing to her as the urban unrest and her fear of black militants in the Sixties had been, that was preferable to the way things used to be, having to pretend that black people did not exist, looking through them on the street.1

And yet she herself could seem so Southern, in the captivating cadences of her speech, the brilliant charm of her manner. Her whole body was engaged when she got into the rhythm of her conversation. She touched her hair; she touched the arm of the person she was talking to; her hands conducted the music of the point she was making. When being ironic, mischievous, she rocked her shoulders like Louis Armstrong. She swayed with laughter—she had a most beautiful smile. She agreed that her dance was intended to disarm, a disguise she could hide behind so that she could get away with letting someone have it, really giving that person the once-over for the shortcomings of his or her argument. For Hardwick, the segregated South of her upbringing made for a weak argument, and she was at her most pleasantly cutting when holding forth, as she liked to describe it, about the white Southerner’s pretensions, particularly those associated with the old family silver and what she called the region’s “false Cavalierism.”

Elizabeth, the narrator of Hardwick’s acclaimed autobiographical novel, Sleepless Nights, published in 1979, reflects that her mother

had in many ways the nature of an exile, although her wanderings and displacements had been only in North Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, and Kentucky. I never knew anyone so little interested in memory, in ancestors, in records, in sweetened back-glancing sceneries, little adornments of pride. Sometimes she would mention with a puzzled frown The Annals of Tennessee, by her grandfather with the same name, but she had never read it.

In Hardwick’s New York home, a copy of The Annals of Tennessee to the End of the Eighteenth Century, by J.G.M. Ramsey, published in 1853, was stored on a closet shelf, left to hold its own against several volumes on the same shelf that had to do with the history of Robert Lowell’s family and the writing of Life Studies, including old Mrs. Lowell’s Jung. Fiction, yes, but also in real life to have come from a poor family was a little less shaming if that family’s roots went back to respectable Scottish Presbyterian stock.

Hardwick said she couldn’t write about herself, because she wasn’t that interested in herself in that way. She said she also for some reason could not write about those she had cared for the most, except obliquely. Hardwick, the ninth of eleven children, loved her uncomplaining mother and her father with the sweet singing voice who preferred to fish rather than work as a laborer. In Sleepless Nights she did not give her narrator the story of a brother, a professional gambler, whose winnings at the track paid for her graduate school tuition. He died young.

In Sleepless Nights, Hardwick’s themes derive from her unlikely beginnings and her lucky escape, and the guilt that when young she noticed the difference between herself and her family, and had judged them for it. But her narrator is primarily an observer of others. Hardwick said that she could not account for herself as a character, or maybe she could explain herself all too easily, already a Communist as an undergraduate at the University of Kentucky, the radical politics having been encouraged by her father’s sympathies as a sensitive working man. Hardwick said with some relief that she had been on the anti-Stalinist left, but even before the Moscow trials of 1938 the Communist Party line that the Black Belt in the South constituted a separate nation showed her that the Comintern had no grasp of political reality in the United States.

Hardwick liked to say that her ambition when she graduated from college in 1939 was to become a New York Jewish intellectual, one of the champions of literary Modernism. She took the Greyhound bus north to the Taft Hotel at Times Square and got her American edition of Finnegans Wake, hot off the press. It amused her to remember how fashionable as a field of study T.S. Eliot had made John Donne and the seventeenth century when she entered the Ph.D. program at Columbia University in 1940, a memory she put into a late short story, “The Bookseller.” Unlike the narrator of “Evenings at Home” who has been away from home for a while, Hardwick made the train journey south every summer to endure weeks of restlessness, until in 1944 she went home to tell her parents that she was quitting school to become a writer. Her mother asked if that meant she wasn’t going to be a teacher after all.

Advertisement

That same year Hardwick published her first short story in The New Mexico Quarterly Review. Two more stories soon followed in Harper’s Bazaar. These were enough. The work provided her with what she called the validation of seeing her name in print. It was also enough to get her a contract that took her, if not back to Manhattan, then at least to her sister’s on Staten Island, where she finished her first novel in one sweltering summer. The Ghostly Lover (1945) brought her to the attention of Philip Rahv, who, along with William Phillips, edited Partisan Review. To be associated with the leading journal of radical politics and intellectual culture in the 1940s gave her an identity. Rahv was drawn to Hardwick’s skepticism, her slashing questions, and she found a freedom of voice in the essay form that she did not at the time feel in fiction.

Through Partisan Review, Hardwick met Mary McCarthy. The two writers became close very quickly, and soon their intellectual challenges and their bright red lipsticks were the terror of Greenwich Village cocktail parties. They were younger and prettier than most of the white radical women on the scene back then. While Hardwick didn’t worry that in a review she might repeat what others thought, when it came to the writing of fiction, she felt so much in the shadow of the older and already famous McCarthy that her biggest problem some days, she said, was in just trying to stake out territory in the contemporary woman’s experience that her friend hadn’t already covered in short stories of dazzling confidence.

Hardwick’s subject in “Evenings at Home” and in another effort for Partisan Review, written around the same time, “Yes and No,” is escape, the exile, that migration from the small town to the big city, and not just any big city. New York City at its most intriguing was to Hardwick a gathering of refugees, such as the distinguished theologian who had fled Nazi Germany in her first story to appear in Partisan Review, “The Temptations of Dr. Hoffmann.” She was fascinated by a city populated by seekers, everyone with a story, a reason he or she had to get away, if only from Brooklyn.

To see her first serious love for the ordinary brute he is gives Hardwick’s young woman in “Evenings at Home” a lively sense of shame. The narrator of “Yes and No” is fluent with apologies to the image of the loyal but dull man she never considered good enough to marry. The graduate student befriended by the tense exile family in “The Temptations of Dr. Hoffmann” has been introduced to them by a divinity student from home whom she despises. Remembrance of the inappropriate man—territory in fiction where Hardwick could perhaps stake a modest claim. The difference between her and McCarthy is that the potential for degradation in such a situation is not an occasion for comedy.

For Hardwick, a woman’s escape from the small town includes nearly having settled down with the wrong guy and therefore lived someone else’s life. The intellectual life her young women narrators believe they were meant for is clear in their tone, but Hardwick makes them careful to mock their own aspirations. Her shrewdness of style is already apparent in these early stories, but she abandoned the strong personality of her first-person voice in fiction for three decades.

Hardwick met Robert Lowell in 1948, when she was summoned by a group of literary wives to a midtown hotel to be questioned as to whether she was having an affair with Allen Tate. (Many years later when Tate’s biographer informed her that Tate had claimed that they had had an affair, she said that Tate could have an affair with her for his biography if it meant that much to him.) She was given martinis at her interrogation, needed help when some of Tate’s friends, Lowell among them, broke up the meeting, and as Lowell handed her into a taxi, she turned and threw up at his feet. She once hid in a doorway along Second Avenue when she saw him coming, so great was her attraction to him.

Advertisement

They met again, at Yaddo, toward the end of 1948. He was just arriving; she was leaving. Lowell asked Hardwick to come back and she did. Elizabeth Bishop warned him against her; McCarthy considered Hardwick to be getting above herself. Lowell’s doctor advised her not to marry a man so tormented in mind, but in 1949 she did. She said she was only grateful for the life he opened up for her and one of the reasons she resisted entreaties to write about their time together was that it had been so extraordinary. She said to do justice to the poets and thinkers they’d known she would need the gifts of Dostoevsky. Thirty years after his death in a taxi at her door in 1977 she said she still wept for Lowell’s genius.

In her fiction, Hardwick would write about women for whom the men they married were their significant experience. She didn’t consider herself one of them, because Elizabeth Lowell never wrote anything, she said. Yet Hardwick more than anyone was aware of what a liberation it was for her to produce the essays on women and literature that went into Seduction and Betrayal after Lowell left her for Caroline Blackwood in 1970. (He and Hardwick divorced in 1972. Before Hardwick, Lowell had been married to Jean Stafford. “Robert Lowell never married a bad writer,” Hardwick said.) Similarly, when she wrote Sleepless Nights, she recognized that she hadn’t published fiction in the first person in thirty years, and that maybe Lowell’s death had moved—or freed—her to do so.

In the 1950s, Americans were traveling abroad again, not having been able to go to Europe since the 1930s. Lowell and Hardwick lived in Holland and Italy for a time, excited by the art, the churches, the opera, meeting artists and writers. Lowell had come to a sort of impasse with his third book, The Mills of the Kavanaughs (1951). But after the death of his mother in 1954, they returned to the US. New York’s cultural life had been quickened in the previous years by the intellectuals driven out of Europe by fascism. Moreover, a new generation of American writers was emerging in the city. However, Lowell and Hardwick ended up in Boston, Lowell’s home, his inheritance. Their years in Boston saw Lowell accomplish a revolution in his work through the “confessional” poetry of Life Studies (1959). But for Hardwick, wrinkled, spindly-legged, depleted, provincial, self-esteeming Boston was a deprivation:

In Boston there is an utter absence of that wild electric beauty of New York, of the marvellous excited rush of people in taxicabs at twilight, of the great Avenues and Streets, the restaurants, theatres, bars, hotels, delicatessens, shops. In Boston the night comes down with an incredibly heavy, small-town finality. The cows come home; the chickens go to roost; the meadow is dark.2

Hardwick toiled at her fiction, and her ambivalence about the short stories she published in the 1950s, her Boston years, stemmed from her thinking them entirely too conventional in structure and intent, in her handling of character, in her just trying to have plot. But Hardwick was altogether too hard on herself in her evaluation of this work. The stories of this period are case studies, strenuous explorations of motive and temperament, a reflection maybe of the influence of psychoanalysis in the culture at the time. Hardwick once laughed that Freud had uncovered the last great plots in fiction.

In “A Season’s Romance” (1956), a bored art historian is joined by her mother in the exploitation of a generous but unsuitable man. In “The Oak and the Axe” (1956), a career woman mistakenly believes her love can redeem an indolent dreamer. Instead, his bachelor habits destroy her carefully built-up life. A professor’s sense of rivalry with a younger colleague in “The Classless Society” (1957) leads to his realization that he is trapped in his life. In “The Purchase” (1959), a successful portrait painter can’t stop himself from embarking on a possibly destructive affair with the tough wife of a rising young Abstract Expressionist. For Hardwick, the individual is also a type, doomed to struggle against his or her general outlines in the psychological drama of everyday experience.

The omniscient narrator that Hardwick employs in each story of the 1950s projects something of the gritty dynamism of the city, that feeling that one could turn a corner and one’s life could change. At the same time, her voice is somewhat remote, however forceful and fast her observations. One can almost feel Hardwick working to restrain herself as the teller, to contain her narrative energy, to stay behind the camera, or offstage. Then, too, these New York stories appeared in The New Yorker and in an odd way that is what Hardwick most had against them when she was asked years later to consider collecting them. She could not forgive herself for having spent so much time trying to be accepted by The New Yorker, trying to fit herself to what in her mind was a sort of formula in fiction. It was not that she found this work insincere. If anything, it was too earnest for her, too constrictive.

As intelligent as Hardwick’s fiction of the 1950s was thought to be, her reputation, like James Baldwin’s, came more from her accomplishments in the essay. Hardwick had kept up her connection as a book reviewer for Partisan Review throughout the 1950s and the essays she wrote for Harper’s during this time were striking in their candor, literary and cultural range, and grace of expression. Her work for Harper’s was largely due to the admiration of a young editor, Robert Silvers. Hardwick and Lowell had resettled with their daughter in New York City by the time The New York Review of Books was founded in 1963, with Silvers and Barbara Epstein as its coeditors. Hardwick said more than once that her association with The New York Review saved her as a writer. She was given the freedom to be utterly herself, to contemplate works and events as she chose. She said that Robert Silvers never failed to make her feel that it was important for her to write on a given subject, that her views were needed. He had a way of coaxing the work out of her. He represented the ideal reader for her, because he was entirely of her view that the essay was as much imaginative prose as fiction.

The peculiar demands of Hardwick’s home life as Lowell’s fame increased, her constant vigils of his seasonal agitation, could accommodate the essay; she could find blocks of time in which to concentrate long enough for a certain number of pages, but not longer. In addition, the political upheavals of the time formed a tumultuous background for work, leaving little chance for the reflection she believed she needed for fiction. What was happening in the larger world did not speak to her as fiction. It was more engaging for her as a writer to be a witness, to go to the funeral of Martin Luther King, for example.

Hardwick published no fiction in those years when first back in New York—apart from wicked little parodies in The New York Review under the name Xavier Prynne, such as her lampoon of McCarthy’s best seller of 1963, The Group.3 Where the frankness of the sexual scenes in McCarthy’s early fiction had been for Hardwick episodes in McCarthy’s career of dissent, The Group struck her as rather conformist and a cliché, and she noted in it also a loss of irony. But Hardwick was out of step with the sexual revolution and out of sympathy with attempts to be explicit about sex on the page. She had never taken Anaïs Nin or Henry Miller seriously; she admired John Updike, but not the male point of view in his descriptions of what went on in the back of the car. She shrank from a kind of women’s or gay fiction that was too intent on recording the sexual act. She admitted to a degree of prudery, but she was adamant nevertheless that nothing dated fiction as quickly as sex scenes. It was not what Humbert Humbert said, it was how Nabokov made him say it, “a rhapsodic call to literature itself.”

Hardwick sometimes gave the impression in the 1970s that the influence, the success, of feminism had taken her by surprise. She wished she could retract what she had written in 1952 about “the briskly Utopian” and “donkey-load undertaking” of The Second Sex. What had not been possible for women then was a different matter twenty years later. Yet she wasn’t interested in what young theorists called the critique of patriarchal society, she just couldn’t bring herself to talk that way, or to endorse hostility to men as men, or to denounce Lowell publicly for the intrusive poems of The Dolphin (1973). That all seemed a fad to her anyway. She did not need literary politics to be interested in women writers. Much as she sympathized with the effort Peter Taylor put into his work, or as fascinated as she was by Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, Hardwick never wanted to be a Southern writer. But she was greatly invested in her identity as a woman writer. She cared about Hawthorne’s injustice to Margaret Fuller.

She thought about women writers and measured herself against them. She watched Joyce Carol Oates at committee meetings and concluded that she must write all the time, as if under a spell. Only Elizabeth Bishop’s stories deserved to be talked about as “Kafkaesque.” She treasured George Eliot and Joan Didion for the way they could handle information, for what she called their masculine knowledge of systems, how things work, what the world is made of. She did not subscribe to Beauvoir’s view that in essence there was no difference between men and women. (Sometime in the early 1960s in Paris at a dinner for Alice B. Toklas, by then a tiny, shriveled-up figure with a mustache, Hardwick felt someone jab her in the ribs. It was Katherine Anne Porter, who whispered, “Honey, if I looked like that I’d kill myself.”) Hardwick believed that society still had such different rules for women that they continued to experience life on another level from men—even if medical science and changed social attitudes had lifted the threat of pregnancy and the fear of disgrace, so that biology was no longer destiny only for women.

Unlike Susan Sontag, Hardwick as a woman writer did not resist the category of women’s literature and she took for granted that its natural tendency was, like black literature, toward the subversive. But it was not enough that a woman writer merely give the woman’s side of things; Hardwick was disappointed when a work of fiction by a woman did not challenge the novel as a form. It was almost a cultural obligation, given the intense experimentation in fiction that was taking place in America in the 1970s. Hardwick would assert in two provocative essays on the state of fiction that social change, life itself, had removed the traditional motives for fiction and how it was constructed.

Yet experimentation could go too far, drain the text of its pleasure—Nathalie Sarrault was not a writer to curl up with at night. By challenge, Hardwick meant something more about what the novel was looking at, how its narrative developed, because of who was doing the looking, more than she did taking hammer and chisel to the novel as an edifice. What transfixed Hardwick about Renata Adler’s Speedboat (1976) was her narrator’s indifference to anything other than her own perceptions. Involvement with a critical self suited the life of the single woman. To be a woman alone in the city in the 1970s was nothing like what it had been when Hardwick first came to New York, when to enter a bar or a restaurant unescorted was the first of many nervous calculations of an evening. Hardwick felt guilty that her first thought was of the independence she’d be giving up when in 1976 at Harvard, Lowell, exhausted by his stormy life with Blackwood, whom he still loved—she represented Aphrodite and ruin, he said—asked Hardwick if she’d consider taking him back.

It wasn’t so much that Hardwick found her voice after Lowell’s death and the publication of Sleepless Nights. She resumed use of the first person in fiction. It was a restoration of her narrative freedom, the reconciliation with the past. But the first person had been there all along at the core of her essays, so distinct was her prose style. She’d irritated Mary McCarthy in an appreciation of her friend’s work when she wondered if The Company She Keeps (1942) and Memories of a Catholic Girlhood (1957) weren’t richer, more aesthetically satisfying than A Charmed Life (1955) or The Groves of Academe (1952) because they have an element of the dramatic tension of autobiography—self-exposure and self- justification. In Sleepless Nights, Hardwick relaxed this autobiographical element in her own writing. The work to which it perhaps can be most usefully compared is Colette’s The Pure and the Impure. Hardwick also managed to dispense with the apparatus of the novel, the frame of storytelling that she’d always found so tiresome. She reasoned that for a woman writer, sensibility is structure.

In her late short stories, Hardwick is interested in distillations of experience, moments in which a narrator and her subject, the object of her city dweller’s curiosity, meet and achieve parity, are equally aware of each other. Or her first-person narrator simply ceases to be in the picture, behaves in the grand manner of an internal narrator, and no one notices. Everything flows so naturally that readers are comfortable in their relationship with her as everybody’s narrator. It’s a tour of a mood or the inside of someone’s head and at every place where she turns aside, moves forward, backward, takes up position again, or talks to herself, she remembers her readers and appeals to their experience, like nineteenth-century novelists. She parts the shades to show another scene, before walking back on stage, into place.

If Hardwick’s work in the short story shares a theme throughout her writing life, it would be her attention to urban characters, city possibilities, neglected histories. She wrote about men who did not quite add up, but not lawyers or businessmen. Her characters are people afflicted one way or another with the romance of print, the thunder of the intellectual life. Those women who have some culture in Hardwick’s stories can be consoled. As women left to fend for themselves in the city, they are softer, less bitter than those in Josephine Herbst, a writer Hardwick admired in her radical youth.

A writer’s work has a life separate from that of the writer, Hardwick maintained, but she liked to read the work in view of the life, because the act of composition was for her above all a human drama. Maybe that was why she preferred the mournfulness of Donald Barthelme to the demanding, cloaking abstractions of Thomas Pynchon. But Hardwick didn’t want anyone to say that the time in which she could have written fiction got used up taking care of husband and child. (A child is a sacred duty.) She knew that her own diffidence had as much if not more to do with how little fiction she wrote in a career that spanned six decades. She couldn’t just sit down and see what happened. That was not how she approached fiction.

She said she couldn’t start with “The sun was shining.” She had to have an idea; and always there was the problem of the idea that was not good enough. Sometimes, when at work on her late stories, a kernel of memory would stand for the idea she was trying to express, or she would find an image so haunting she would have to investigate the atmosphere around it, and the story’s details would accrue from there, as a series of illuminations. Hence, “Back Issues” (1981) is a vessel for the emotion that overcame her when she remembered the young, somberly dressed John Berryman lecturing on A Winter’s Tale. The same temperament is at work in her few late stories as in the early ones from her Partisan Review days, and sometimes in the type of narrator, the smart girl ambivalent about her small-town roots. Her voice, like Baldwin’s, never aged.

But Hardwick’s diffidence frustrated her, because she knew that it was an expression of her perfectionism. She would tell her students that genius and perfectionism only looked alike, but they were not at all the same thing. Perfectionism had an inhibiting effect. She admired fluency, expansiveness in other writers, and cursed her own inability to spin anything out. She remembered how, as a student, she would finish writing in her blue exam book, and look in amazement at the rest of the class, still scribbling away. She got poor grades, because she could not bear to repeat to teachers information she knew they had already. The waste of time was morally offensive to her young self. Better to say too little than too much, Chekhov said, and there was never anything Hardwick could do as a writer about her economy of form, her compression of language.

Hardwick’s diffidence, her perfectionism, had everything to do with her greatest passion: reading. She loved to read; she read faster than anyone in the room and she never skipped a word. When in her old age she said she’d spent the morning reading War and Peace again, she really had. She was a writer because of her love of reading. To read was such an intense experience for her, so transporting, that to write was about the only means by which she could find relief for the emotions that built up.

Virginia Woolf read poetry before she wrote, and Hardwick was touched by the echo of the Elizabethans from Leslie Stephen’s library in the dialogue of The Waves. Nadezhda Mandelstam had to commit her husband’s work to memory and Hardwick thought that Mrs. Mandelstam’s immense two- volume laying out of her husband’s and her country’s fate was that body of work releasing itself in her, uncoiling at long last. However, instead of saying that Hardwick wrote a poetic prose, one should say that she composed prose line by line, as though it were poetry. She couldn’t go on to the next sentence if the one before it wasn’t right. One line determined the color and purpose of the line immediately to follow and the one after that. Everything came back to language, or through language. Just before “Back Issues” was printed, she rushed with changes to The New York Review’s offices. “I thought, ‘What are these prancing banalities?’ You think it has the freedom of the sketch, but once these constructions are framed, they seem too tight.” She had a special affection for the small, seemingly random lyric work—Rilke, Baudelaire.

Hardwick liked to say that there were really only two reasons to write: desperation or revenge. Yet she wrote to honor the literature she cared about, which was why in fiction she was so easily discouraged. She could always think of someone whose work she liked better than what she proposed to do on the same subject. She loved the glamour of midtown, but never doubted that her true subjects were back in those bohemian rooming houses, with the socially marginal who somehow inspired her to capture the cultural drift, the movement of a life, in an arresting phrase. In her short stories, the qualities that make her prose an art that cannot be imitated, its rhythmic, pure sound, its control and texture, its daring intellectual pitch—all of these shine on and on and on.

-

1

This essay is drawn from the introduction to The New York Stories of Elizabeth Hardwick, to be published by NYRB Classics in June.

↩ -

2

”Boston,” from Harper’s, collected in A View of My Own: Essays in Literature and Society (Farrar, Straus, 1962).

↩ -

3

”[The Gang](/articles/archives/1963/sep/26/the-gang/),” The New York Review, September 26, 1963. The two friends knew how to get at one another. McCarthy was absolutely sure that Randall Jarrell in his satire of academic life, Pictures from an Institution (1954), based the character of Gertrude on Hardwick, when Hardwick said that it was so clearly McCarthy.

↩