On February 13, 1898, the French newspaper Le Figaro carried a cartoon by the caricaturist Caran d’Ache. In the first frame the bearded man presiding at a family dinner as a manservant brings on the soup says, “Above all, we must not talk about the Dreyfus Affair.” In the second, above the caption “They did talk about it,” pandemonium has broken out. Chairs are upturned, crockery is flying, and the diners—both men and women—are attacking each other with forks, cruets, bottles, and their bare hands.

This cartoon has come to symbolize the passion and divisiveness of the Dreyfus Affair, which for several years on either side of 1900 churned up the French political scene. In a bizarre and fascinating way the case of one man convicted of treason—rightly according to some, wrongly according to others—and imprisoned for four years on a remote island divided a nation. The noise reached from the law courts and halls of parliament into public meetings and onto the streets, and at the same time into salons, dining rooms, and even bedrooms. It mobilized politicians and intellectuals, army officers and clergymen, Catholics, Protestants, and Jews, anti-Semites and nationalists. The issues that it raised looked back to the French Revolution and forward to the Holocaust.

Three recent studies of the Dreyfus Affair show three different ways of writing about it: as a detective story, as a war of ideas, and as a human and social drama. Why the Dreyfus Affair Matters by Louis Begley, lawyer and author of Wartime Lies, among other books, puts in the foreground the detective story, with its elements of anti-Semitism, although his writing is particularly powerful in drawing lessons for American society after September 11. For the Soul of France: Culture Wars in the Age of Dreyfus by Frederick Brown, who has written biographies of Flaubert and Zola, sets the affair in the context of ongoing conflicts in France since the Revolution. Dreyfus: Politics, Emotion, and the Scandal of the Century by Oxford historian Ruth Harris, who has unearthed a mass of new documentation, is an extraordinary study of the affair as a tragic drama that swept up a man, his family and friends, and more widely French society and the French state.

Accounts of the Dreyfus Affair as a detective case begin in September 1894, when a cleaning woman who was also a spy in the pay of the Statistics Section, or counterespionage arm, of the French army found a document—the so-called bordereau—in the wastepaper basket of the German military attaché in Paris and forwarded it to her masters. It contained a number of military secrets, including information about a 120-millimeter cannon that the French were developing. The French army had not yet recovered from its defeat by the German army in 1870, which toppled France from its European preeminence and resulted in a united and powerful German Reich. It was a matter of urgency to catch whoever had passed the document to the Germans.

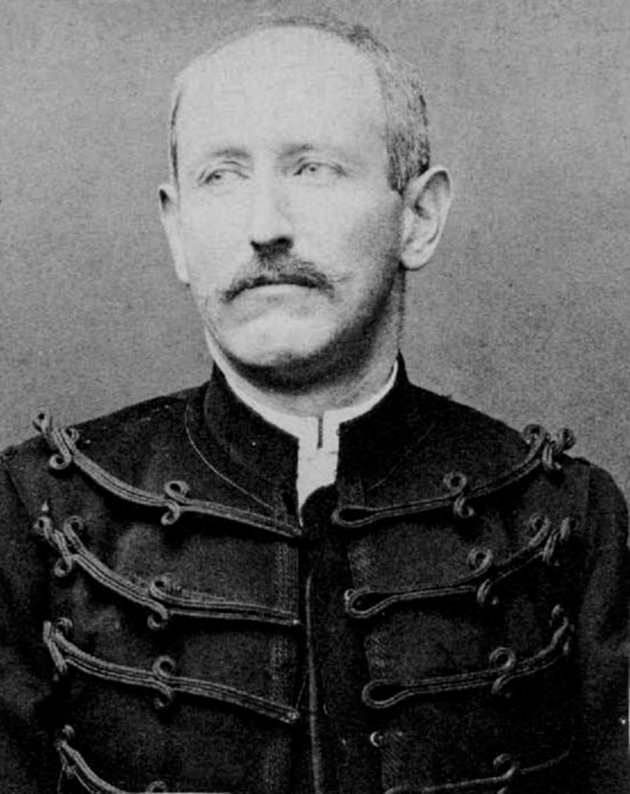

Suspicion fell on a staff officer, Alfred Dreyfus, aged thirty-five and of Jewish origin. Most European armies at the time did not have Jewish army officers, but in France a controversial exception was made for an elite of assimilated Jews who were promoted by meritocratic means into the General Staff. A wealthy and happily married family man, Dreyfus had no motive to sell military secrets, but handwriting experts were brought in by high- ranking officers and Dreyfus was arrested. In reality the guilty man was Major Ferdinand Walsin-Esterhazy, whose character and motives were all too clear. Begley explains that he was

a descendant of the illegitimate French branch of the ancient and illustrious Austro-Hungarian family, which had never acknowledged the French offshoot. An amoral sociopath, Esterhazy lied, intrigued, and swindled obsessively. He was chronically in debt; his wife, a French aristocrat who had married him despite the vehement objections of her family, had found it necessary to take legal measures to protect her small personal fortune from his depredations.

Esterhazy, however, was Catholic and aristocratic and well connected with the military caste who controlled the French army. It was Dreyfus who was court-martialed and, in a ceremony that took place in the wide courtyard of the École Militaire, he was stripped of his badges of military honor and had his sword broken in two. The army played into the hands of the watching crowd, for whom it was obvious that a Jew could not be a French patriot. Ruth Harris quotes the eyewitness account of the nationalist writer Maurice Barrès:

Judas! Traitor! It was a veritable storm…. The poor wretch releases in all hearts floods of intense dislike. His face that marks him as a foreigner, his impassive stiffness, create an aura that even the coolest spectator finds revolting…he was not born to live in any society. Only the branch of a tree grown infamous in an infamous wood offers itself to him—so that he could hang himself from it.

Dreyfus was not executed, and did not commit suicide. He was convicted and sentenced to deportation and imprisonment for life on the malaria-infested Devil’s Island off the coast of French Guinea, where he was kept in a small cabin surrounded by a high palisade to shut out views of the sea and manacled by night to an iron bedstead. The shackles suggest to Begley an association:

Advertisement

Shackles—the “three-piece suit” consisting of leg irons, handcuffs, a chain worn around the waist as a belt, and two chains that connect the leg irons and handcuffs to the chain belt—are constants at Guantánamo whenever prisoners leave their cells, especially when they are on their way to and from an “interrogation booth.”

Dreyfus was supposed to die in prison but he stubbornly protested his innocence and was sustained by letters from his wife Lucie, which were censored and transcribed to eliminate the possibility that they were sending coded messages. Thousands of miles away in France his older brother Mathieu, the Jewish anarchist Bernard Lazare, and the Jewish journalist and politician Joseph Reinach began a campaign to have his case reopened. They needed to move carefully as the anti-Semitic press was quick to denounce the machinations of a Jewish “syndicate.” However, they had an ally in the army, Major Georges Picquart, who was appointed head of the Statistics Section in 1895 and came to suspect that the true culprit was Esterhazy. Begley cites the description of Picquart by a young diplomat, Maurice Paléologue:

Paléologue recalled Picquart as “tall, slim, elegant, with a fine mind, both judicious and caustic, usually concealed behind an air of distant and stuffy reserve.” It was this model officer, incarnating all the traditions of the army and the army General Staff—including a dose of conventional anti-Semitism—who became Dreyfus’s champion and savior.

Picquart reported his findings to General Charles-Arthur Gonse, deputy head of the General Staff, but Gonse was not going to let such details get in the way of the conviction the military stood by. “What do you care if that Jew rots on Devil’s Island?” he asked Picquart. Picquart was relieved of his responsibilities and sent on a dangerous mission to Tunisia.

Picquart, like Dreyfus, came from Alsace, which had been annexed by Germany from France as a war trophy in 1871. Most Alsatians stayed put and came under German rule, but 164,000 who wished to remain French citizens abandoned their homes and property to come to France. Alsatians who made this decision were intensely French, but because many more stayed in German-controlled Alsace they were open to accusations of treachery.

Ruth Harris shrewdly unpicks “the Alsatian connection” behind the campaign to reopen the Dreyfus case. Here a key figure was Auguste Scheurer-Kestner, a senator from an industrial family in Alsace who had been sent to prison for his republican beliefs and had walked out of the National Assembly in 1871 when it abandoned Alsace to Germany. A respected statesman, he spoke to the president of the Republic about Esterhazy’s guilt but in December 1897 the prime minister flatly told the Chamber of Deputies that there was “no Dreyfus Affair.”

Esterhazy was court-martialed in January 1897 simply to clear the air, and immediately acquitted. The army was nevertheless concerned that the evidence against Dreyfus was flimsy in the extreme. Major Joseph Henry of the Statistical Section, who was of peasant stock, red-faced, and not very bright in contrast to the elegance, alertness, and intelligence of Picquart, was the man to dig his superiors out of a hole. Begley explains:

What was needed was a new dossier…. Its centerpiece would have to be a document in which Dreyfus was named and clearly revealed as a traitor…. Since there was no such document, it would have to be created. The task did not daunt Henry. He would fabricate an unrebuttable piece of evidence—it came to be referred to as la massue (the club)—that from then on would be used to smash anyone who raised doubts about Dreyfus’s guilt.

The Henry forgery brings to a climax the story of the Dreyfus Affair as a detective story, or rather the Dreyfus case, which unraveled in a half-light of conspiracy, fabrication, and lies.

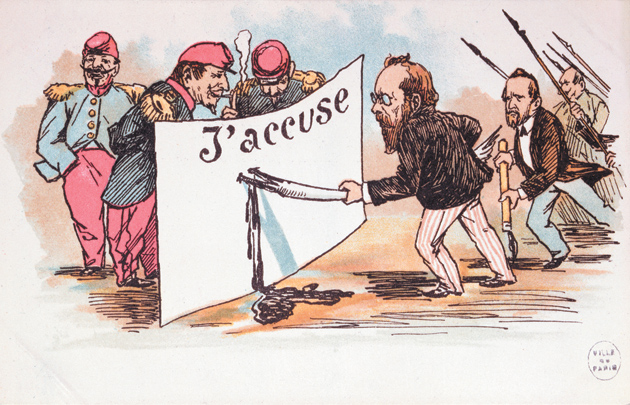

The affair, however, can equally be narrated in a second way, as a war of ideas. For this the starting point is the involvement of the best-selling novelist Émile Zola, who was seduced by the affair almost as if it was the plot of one of his novels. This time, however, he was going to be a leading character. Incensed by the acquittal of Esterhazy, he wrote an open letter to the president of the Republic, entitled J’accuse!, and published in 300,000 copies. It was designed to expose the framing of Dreyfus and endless cover-ups by the top military leaders. Zola wrote:

Advertisement

Certainly we have nothing but love and respect for the army that marches out at the first sign of danger, which would defend the French soil, which is the whole people. But we are talking about another sort of army…. That army is the sabre, the dictator who may be forced upon us tomorrow. And God knows I will not piously kiss the hilt of a sabre…. My act today is nothing but a revolutionary means of hastening the explosion of truth and justice.

For Frederick Brown, this relaunched the battle “for the soul of France,” which since the French Revolution had set the apologists of the Enlightenment against the supporters of the monarchy and Catholic Church:

For everyone 1789 was the inevitable reference point.

There were those on the one hand who held that France would betray the best of herself if she did not remain loyal to the eighteenth-century figures who had fathered the Republic. On the other hand, “intransigeants” committed to the ideal of a Catholic monarchy anathematized the Enlightenment. In their view, divine grace was needed, and France could receive it only as a penitent mindful of the sins she had accumulated over the course of eighty years.

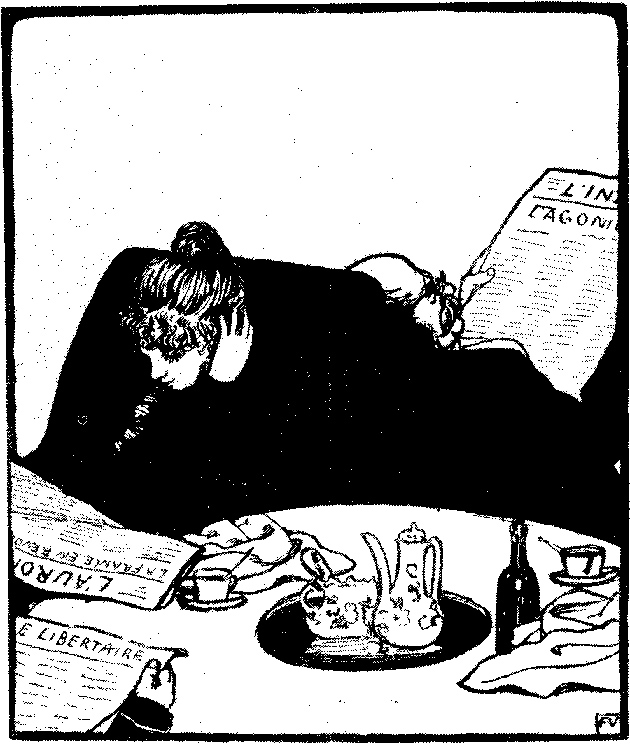

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris

‘En Famille’ (At Home), showing a family reading about Zola’s trial. The husband reads the nationalist L’Intransigeant, the wife the opposing L’Aurore, while a third person reads the anarchist Le Libertaire. Woodcut by Félix Vallotton from Le Cri de Paris, February 13, 1898.

Brown traces this struggle through France’s revolutions in 1789, 1830, 1848, and the Paris Commune of 1871, and its succession of restorations. He contrasts the publication of Ernest Renan’s Life of Jesus, which presented Jesus as a historical figure, with the building of Sacré Coeur on the hill of Montmartre to apologize to God for the atrocities of the Commune. After 1870, of course, France was a republic that set about removing the influence of the Church in education. As a restoration of the monarchy looked increasingly unlikely, defenders of the old order put their faith in the Catholic Church and in the army, whose officers defended the same values of order, hierarchy, and tradition.

The Dreyfus Affair gave an unexpected opportunity to Catholics and militarists to attack the Republic. They argued that it was run by a band of Jews and Freemasons who were betraying the French nation. Far from being acclaimed as a visionary, Zola was himself put on trial for political libel. Outside the Palais de Justice anti-Semitic bands bayed for blood and anti-Semitic riots broke out across France and Algeria. Army generals lined up as witnesses to take their revenge. Chief of Staff General Charles Le Mouton de Boisdeffre put the army’s case robustly:

You are the jury, you are the nation. If the nation does not have confidence in the leaders of the army, in those who bear the responsibility for national defense, they are ready to surrender that onerous task to others. You have only to speak. I will not say another word.

There was no explosion of truth and justice. Zola was sentenced to a year in prison. He appealed, lost, and fled to England. His cause was supported by intellectuals who signed petitions and campaigned in the press. One of them, Léon Blum, future prime minister of the Popular Front government in the 1930s, recalled: “Writers, scholars, artists, professors!… This penetration of ‘intelligence’ filled us with joy.”*

A Ligue des Droits de l’Homme was formed to defend France as the country of the rights of man. Against it, however, was ranged the Ligue de la Patrie Française, to which Maurice Barrès declared that nationalism was best cultivated by a love of one’s ancestors and of the provinces where most people grew up, far from dissolute, oppressive Paris. The affair even gave a new lease of life to a new breed of monarchists such as Charles Maurras, who denounced the Jews, Freemasons, Protestants, and foreigners who ran the Republic and argued that France would not be great again until, like Britain, Germany, and Russia, it restored the monarchy.

This is the Dreyfus Affair as an ideological or culture war. Its black-and-whiteness is satisfying, but it is a black-and-whiteness developed by French historians who see themselves as high priests of the Republic. The argument of Ruth Harris is a good deal more subtle. In her view, French society was far too complex and multilayered to be reduced to a struggle between light and darkness, which was in any case a construction of the combatants. When writers and academics gathered signatures in 1898, Léon Blum fully expected Maurice Barrès, as a well-known writer and dandy, to join up. He did not and by way of attack on the Dreyfusards coined the term “manifesto of the intellectuals.” Writers and academics, says Harris, were separated less by fundamental opposition than by what Freud called “the narcissism of marginal difference.” She demonstrates that the Dreyfusards were not all apostles of the Enlightenment; neither were all anti-Dreyfusards benighted traditionalists.

Mathieu Dreyfus, Harris writes, had as a confidante a Norman peasant woman, Léonie Leboulanger, who he thought had the power to see through the obfuscations and lies of the military. Barrès, on the other side, claimed a scientific basis for his blood-and-soil theory of nationalism. From Jules Soury, whose lectures on brain dissection he attended, he derived the idea that the unconscious could be tapped for vital energy and powerful memories from which a rejuvenated nation could be forged.

This is not to deny the importance of cultural wars. Harris, whose previous book was Lourdes: Body and Spirit in the Secular Age, lays bare the decisive influence of the Catholic Church in the Dreyfus Affair and the passion it generated. The Jesuit Father Du Lac sent from his École Sainte-Geneviève to the military school of Saint-Cyr many of the officers who later conspired against Dreyfus. He was also the spiritual guide of Edouard Drumont, author of La France juive and anti-Semitic publicist, who coined the slogan “France for the French,” which is still used today by Jean-Marie Le Pen. Through its best-selling newspaper La Croix, the Assumptionist order, founded by Emmanel d’Alzon, who saw himself as a latter-day crusader against Protestants, orchestrated a powerful campaign against Jews, who were accused of killing Christ. The Dreyfus Affair, says Harris, was nothing less than a war of religion. Protestants, who, like the Jews, were attacked as “cosmopolitans” who had no loyalty to France, feared that the murderous hatred of Catholics might lead to a repetition of the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre of 1572.

Above and beyond conflict, however, Harris shows that both sides used the language of Christian sacrifice and martyrdom for those who suffered for their cause. Lucie Dreyfus, who vowed to wear black until her husband’s return from Devil’s Island, received hundreds of letters of support, mainly from women. Harris remarks that though herself Jewish,

Lucie was cast in Christian terms that associated her with the sufferings of the Virgin…. One Catholic widow from Lorraine and a military family told how she and her mother followed “with a painful and deep sympathy the last stages of your calvary.” …One woman asked Lucie to send a photograph of her husband so that she could give it a “place of honour next to our Christ!” on her mantelpiece.

Major Henry was exposed as a forger in August 1898, arrested, and imprisoned. He committed suicide by slitting his throat and was immediately hailed by nationalists as a Christ-like martyr. Maurras wrote:

You should know that there is not a drop of this precious blood, the first French blood spilt during the Dreyfus Affair, that is not still warm wherever the heart of the nation is beating. This blood is still warm and will cry out until its shedding has been atoned for.

The strength of Ruth Harris’s book is to present the Dreyfus Affair as a human and social drama. Whereas many accounts concentrate on the conspiratorial and public dimensions of the debate, Harris—who has read thousands of the private letters of those involved—moves easily between the public and the private, the intellectual and the emotional. Between the Dreyfusards, she says, “the overwhelming impression is one of friendship, even of love.” The defense lawyer Ferdinand Labori offered to act for Lucie pro bono, despite the threats to him and his family, even including an attempt to assassinate him.

Harris enters the world of the great salon hostesses, who had no vote in the Republic but wielded political influence behind the scenes, in their drawing rooms. Jewish-born Madame Arman de Caillavet was the lover and patron of the novelist Anatole France, who was the centerpiece of her Dreyfusard salon, while Marie-Anne de Loynes, a former courtesan, placed the playwright and critic Jules Lemaître at the center of her anti-Dreyfusard salon and promoted him as head of the Ligue de la Patrie Française. We are led into the deeper, darker side of many characters: the obsession with hereditary madness of Edouard Drumont, and the obsession with his dead mother of Maurice Barrès, whose nationalism of the unconscious may partly be explained by this mourning.

The Dreyfus Affair entered a new phase when the Cour de cassation, or appeals court, annulled Dreyfus’s conviction on June 3, 1899. He returned to France for a retrial that August, but this was held far from Paris in the Breton capital of Rennes, where the Church and military held sway, and the trial was yet another court- martial. The odds were stacked against an acquittal, not least because after long years on Devil’s Island, Dreyfus scarcely struck a heroic figure. In the courtroom Barrès reported that

a miserable human rag was being thrown into a glaring light. A ball of living flesh disputed by two camps of players, and who in six years has not had a moment’s rest, has arrived…to roll in the midst of our battle.

The eyes of the world were on Rennes, but the military judges held fast and again condemned Dreyfus, bizarrely with “extenuating circumstances,” and sentenced him to another ten years. The deadlock was broken by a political fix, as Harris explains, but at the price of the unity of the Dreyfusard coalition. While the political Dreyfusards wanted to carry on the legal fight from the moral high ground, Joseph Reinach and Mathieu wanted only to restore Alfred to his family and petitioned the president of the Republic for a pardon, which was granted.

To prevent the army from organizing a coup against the Republic, the government passed an amnesty law that protected from prosecution anyone involved in the affair. There would be no trial of the military conspirators. Instead, the government punished the “occult forces” represented by the Catholic Church, expelling the Assumptionists from France and completing the secularization of French education.

Why does the Dreyfus Affair matter? asks Louis Begley. There is no single answer and these three authors all have different views. For Frederick Brown there is a happy ending: the triumph of the rights of man over raison d’état, of reason over obscurantism, of the secular Republic over its Catholic and conservative enemies. He ends with the unveiling in 1903 of a statue of Ernest Renan in his home town of Tréguier, on the Breton coast, by Prime Minister Émile Combes, who was determined to secularize all Catholic schools. Combes declared:

We freethinkers who regard Renan as an example do not take shelter behind dogma from the doubts raised by our intellect. The light of reason is our beacon. But neither—unlike the Catholic priest anathematizing dissent from his bully pulpit—do we impose upon others our rule of conduct and way of thinking. All we ask of religion—because we are entitled to do so—is that it keep within its temples, that it limit its instruction to the faithful, and that it refrain from unwarrantable interference in the civil and political domain.

This is a classic exposition of laïcité, the doctrine that the Republic is a neutral space in terms of religion and that the practice of religion—Catholic or Protestant, Jewish or Muslim—must be confined to the private sphere. It is this doctrine that underpins the banning of the Muslim headscarf in French schools, on the grounds that wearing one would violate the neutrality of the Republic.

Ruth Harris sees in this the authoritarian streak that emerged from the Dreyfus Affair—the crusaders for the rights of man then put in place a system that, for all the smooth talking of Émile Combes, was designed to eliminate religion as a political force in French society. This culminated in the separation of church and state in France in 1905, after which no financial support was forthcoming from the state for the churches. Such an event may come as no shock to American readers, but for a hundred years after Napoleon the French state had financially supported the Catholic—and to a lesser extent Protestant—Church, in compensation for the plundering of Church property by the French revolutionaries.

Many French academics have argued that the victory of the Dreyfusards and their rights of man ideology against the forces of anti-Semitism and reaction somehow inoculated France against the fascism that swept Italy and Germany. There was no fascism in France, declared René Rémond in his classic The Right Wing in France, with the exception of a few lunatic individuals and the Parti Populaire Français, which was founded by a renegade Communist. The reactionary right did not return to power until the Vichy regime took over after the defeat of France in 1940. Since it was a puppet regime of the German occupiers, Vichy’s anti-Semitic legislation and the deportation of 75,000 Jews from France could be blamed on pressure from the Germans.

An alternative view, suggested by Ruth Harris, is that after the Dreyfus Affair French anti-Semites and extreme nationalists were not defeated but remained a powerful threat. Brought up in Philadelphia, she remembers the message from Hebrew school:

Had not Theodor Herzl, the father of modern Zionism, clarified his views after reporting on the Affair for his Viennese newspaper? If France, the home of the Revolution, was susceptible to the basest anti-Semitism, was that not proof of the need for a Jewish homeland?

Dreyfus himself survived an assassination attempt in 1908 at the hands of a right-wing extremist. Lucie Dreyfus, Begley tells us, had to hide in a nunnery under a false name during the German occupation and died in 1945. Her granddaughter, deported for resistance activities rather than as a Jew, died of typhoid in Auschwitz in 1944. Maurras described his conviction for collaboration in 1945 as “the revenge of Dreyfus.” His anti-Semitic, extreme-right nationalism was later taken up by Jean-Marie Le Pen, who reached the second round of the French presidential elections in 2002.

The verdict of Louis Begley is even more trenchant. The Dreyfus Affair, he argues, demonstrates the fragility of reason, of the rights of man, and indeed of civilized values when a nation feels itself under threat from an external or internal enemy. In 1890s France the threat was Germany, and Jewish traitors were seen as the internal enemy. Since September 11, Begley writes, America has felt itself equally under threat and responded by resorting to practices comparable to those used against Dreyfus. Guantánamo Bay is America’s Devil’s Island; the use of military justice rather than regular justice repeats the rigged court-martials of Dreyfus; some of the US army officers who protested have had their careers broken, like Picquart.

As each generation confronts the outrages committed in its name, analogies to past outrages become clear, illuminating the present…. Will there be in that generation men and women ready to defend human rights, and the dignity of every human life, against abuse wrapped in the claims of expediency and reasons of state?

Begley concludes that the journalists, judges, and lawyers who have defended Guantánamo detainees against “torture and kangaroo trials” are worthy heirs of the Dreyfusards. That President Obama has pulled back from his decision to close Guantánamo Bay makes it clear that the battle is not yet over.

This Issue

June 10, 2010

-

*

Léon Blum, Souvenirs sur l’Affaire (Paris: Gallimard, 1935), p. 101.

↩