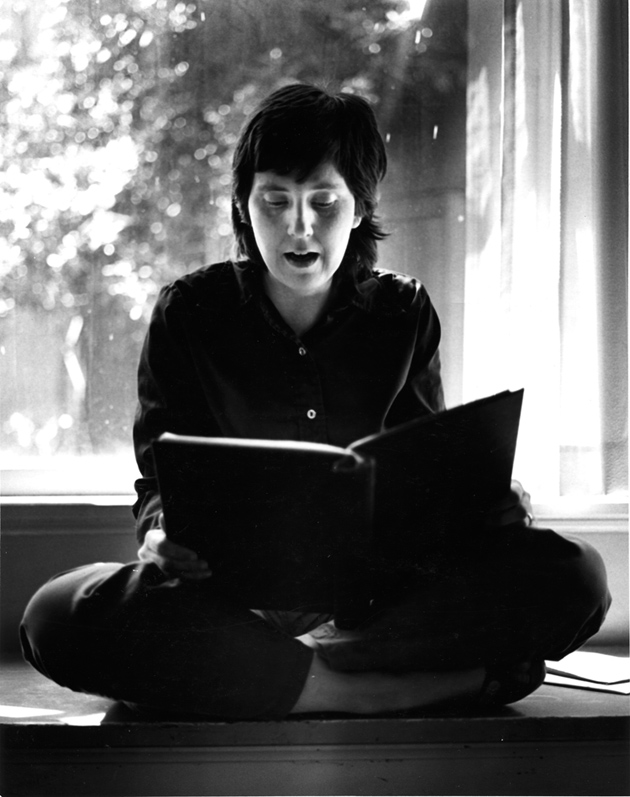

Joel Meyerowitz/Cincinnati Art Museum

Joel Meyerowitz: Dairy Land, Provincetown, 1976; chromogenic print from Starburst: Color Photography in America 1970–1980, with essays by Kevin Moore, James Crump, and Leo Rubinfien, just published by Hatje Cantz. The exhibition was organized by the Cincinnati Art Museum and will be on view at the Princeton University Art Museum, July 10–September 26, 2010.

1.

John Koethe was born in San Diego, California, in 1945. He is not only a fine poet, but also a professor of philosophy and the author of a book on Wittgenstein’s thought and another called Scepticism, Knowledge, and Forms of Reasoning. The best introduction to his work is North Point North: New and Selected Poems, published in 2002. Reviewers inevitably compare him to Wallace Stevens because both are supposedly fond of philosophizing abstractly. There’s no question that he occasionally sounds like the older poet, as we can readily see in these lines from a poem called “Songs of the Valley”:

And the face of winter gazes on the August day

That spans the gap between the unseen and the seen.

The academies of delight seem colder now,

The chancellors of a single thought

Distracted by inchoate swarms of feelings

Streaming like collegians through the hollow colonnades.

The difference is that Koethe examines ideas in a far more autobiographical way. He tells us about his life and his feelings with a directness that Stevens would never have allowed himself. In a recent essay, “Poetry and Truth,” Koethe says that he considers poetry basically an elevated form of talking to oneself. “And now it seems like years and years ago,” he writes in a poem called “The Narrow Way,” “I started, out of a perverse curiosity/This imaginary conversation on the border between my self/And the unimaginable pith or emptiness within.” For him, what poems do is attempt to convey the experience of an individual consciousness as it tries to make sense of its own existence. Thinking is an important part of it, but the poems he writes are not dry and abstract. They are in the long tradition of the Romantic lyric in which typically some experience or mood summons back an older memory upon which the poem then quietly deliberates.

“Something marvelous is gone,” he writes in a poem. Almost every one of his lengthy, elegiac, and introspective poems has an air of regret and disappointment as they search for a way to recover some moment of complete contentment, “uncontaminated by reflection,” as he says. Koethe compares what he does to poking through the trash for something you threw out by mistake. There are no secrets revealed in his poems. It’s the mystery of small, never-before-remembered events that he is after. Whatever drama or suspense is present in his work comes from the struggle of a mind trying to reach back to a moment lost in time out of which, so the speaker thinks, his true identity was formed:

FROM THE PORCH

…a life traced back to its imaginary source

In an adolescent reverie, a forgotten book—

As though one’s childhood were a small midwestern town

Some forty years ago, before the elm trees died.

September was a modern classroom and the latest cars,

That made a sort of futuristic dream, circa 1955.

The earth was still uncircled. You could set your course

On the day after tomorrow. And children fell asleep

To the lullaby of people murmuring softly in the kitchen,

While a breeze rustled the pages of Life magazine,

And the wicker chairs stood empty on the screened-in porch.

An idealized picture of 1950s America? Of course it is, and yet isn’t this how memory usually works? Koethe is aware of his proclivity to lose himself in sentimental reveries. His poems, as he admits, are more or less convoluted variations on a single emotion and idea: true understanding lay in childhood. That makes them all sound as if they were parts of a long poem, a contemporary American version of Wordsworth’s The Prelude, whose subject once again is the growth of the poet’s mind. Despite that overworked notion, there are a number of eloquent and moving poems in Koethe’s books. I would single out in North Point North “Gil’s Café,” “The Little Boy,” “Pictures of Little Letters,” “The Narrow Way,” “In the Park,” and “The Substitute for Time,” and in his new book “The Lath House,” “Belmont Park,” “Persistent Feelings,” “The Menomonee Valley,” “Creation Myths,” and this one:

CHESTER

Another day, which is usually how they come:

A cat at the foot of the bed, noncommittal

In its blankness of mind, with the morning light

Slowly filling the room, and fragmentary

Memories of last night’s video and phone calls.

It is a feeling of sufficiency, one menaced

By the fear of some vague lack, of a simplicity

Of self, a self without a soul, the nagging fear

Of being someone to whom nothing ever happens.

Thus the fantasy of the narrative behind the story,

Of the half-concealed life that lies beneath

The ordinary one, made up of ordinary mornings

More alike in how they feel than what they say.

They seem like luxuries of consciousness,

Like second thoughts that complicate the time

One simply wastes. And why not? Mere being

Is supposed to be enough, without the intricate

Evasions of a mystery or offstage tragedy.

Evenings follow on the afternoons, lingering in

The living room and listening to the stereo

While Peggy Lee sings “Is That All There is?”

Amid the morning papers and the usual

Ghosts keeping you company, but just for a while.

The true soul is the one that flickers in the eyes

Of an animal, like a cat that lifts its head and yawns

And looks at you, and then goes back to sleep.

This is a poem of disarming directness. It trusts the language we use daily to convey the complex state of mind of someone getting up in the morning, vaguely troubled by the events of the night before and by the feeling that something is missing in his life. “Is that all there is?” he asks himself. Mere being is supposed to be enough, or so the wise men of the East tell us. The answer lies—if there is an answer—in that flicker in the eyes of the cat. We are left hanging, unsure what the cat has conveyed to the speaker, but that’s precisely what makes the poem so rich and worth rereading.

Advertisement

Koethe is not always so subtle. His longer poems tend to overexplain and to go on too long. His almost exclusive reliance on first-person narrative and thus on the same point of view makes that problem even more acute. One tires after a while of a voice that varies too little and one longs for some shift in narrative strategy or for some unexpected image or metaphor to come along and turn the world of the speaker upside down. When he says in an older poem, “The Chinese Room,” “Night is waiting/Like a doctor’s office with its magazines of dreams,” it’s like a bolt from the blue. I wish there was more of that kind of imagination in his poems to complement his fine mind and to give them a bit more range.

2.

Rae Armantrout was born in Vallejo, California, in 1947, but grew up in San Diego and still continues to live there. She spent her twenties in the Bay Area, attending the University of California at Berkeley and befriending a group of poets—later known as “Language poets”—who rejected what they called mainstream poetry. For them, such poetry was dominated by a poetics of individuality and lyrical expressions of the individual self that, like many other forms of culture, were products of an ideological system rather than of the alleged author.

These sound like the kind of ideas influenced by the French cultural and literary theory one heard in American universities at the time. They were characteristic of the only avant-garde literary movement in history that relied on the academy to sanction its practice. The emphasis was to be placed on the language of the poem as a separate closed system, creating a new way for the reader to interact with the work. Believing that there is no such thing as an autonomous self or that the words we use are not actually capable of conveying reality, Language poets try to unmask the verbal fictions that surround such misconceptions. Of course, a theory of poetry that has no interest in the experience of individual human beings is bound to run into intellectual and practical difficulties in a world in which people still fret about the meaning of their lives. If you were stuck in prison, what would you rather have under your pillow: a volume by Emily Dickinson or one by Gertrude Stein?

Although Armantrout has been associated over the years with Ron Silliman, Lynn Hejinian, Charles Bernstein, and other prominent members of this group, her own views regarding language and what it can do are more conventional. The work she likes best, she tells us in an essay called “Why Don’t Women Do Language-Oriented Writing?,” “sees itself and sees the world”:

To believe non-referentiality is possible is to believe language can be divorced from thought, words from their histories. If the idea of non-reference is discarded, what does language-oriented mean? Does it simply designate writing which is language-conscious (self-aware)? If so, the term could be applied to a very large number of writers….

I’m suspicious of it, finally, because it seems to imply division between language and experience, thought and feeling, inner and outer….

Nonetheless, she admits elsewhere in her Collected Prose that she often writes about writing and thinks about thinking. Writing a poem is for her like working on a problem. She is interested in the ways we are estranged from ourselves and the world, and in the ways in which we deceive ourselves as we try to make sense of what we see and think. The poems in her nine collections are usually short and further subdivided by sections. They tend to be roundabout rather than linear. That is to say, they lack an obvious beginning, middle, and end, but are composed of multiple perspectives coming from different voices, some overheard, some her own, and bits of language appropriated from such unlikely sources as commercials, store catalogs, TV cartoons, computer pop-ups, and other similar material. The first poem in her new book, Versed, begins:

Advertisement

Click here to vote

on who’s ripe

for a makeoveror takeover

in this series pilot.

Votes are registered

at the server

and sent backas results.

The relation between sections in her poems and even between stanzas is usually unclear. The effect is of a collection of isolated remarks and notations that deliberately suppress the overall context, and in which the disjunction between individual parts seems to matter more to the poet than their relationship. Even her most admiring critic, Stephen Burt, admits in an essay on her work that her poetry is almost never unambiguous. “The sounds and tones of its stanzas are memorably crafted,” he writes, “but its large-scale arrangements can seem opaque: it can be hard to know why four segments, say, of a thirty-two-line poem require the order they have and not another.” As maddening as that can be for the reader, the parts are often interesting in themselves, so one is usually willing to put off for a while the question of how they link up. Here is an example of what I mean from her book Next Life (2007):

RESERVED

A small dark room

behind each lid,

unoccupied. Reserved?*

“The waiting room was different

this time,” I said, warily,as if someone might have tricked us

into believing

there was just one roomor that there were other times.

*

I’m waiting on a transfer

of poisonamong strung leaves

through the Americasby dictator, no,

dictation.Or I’m going ahead.

Narrative prepares me

to see

whatever I see next.*

Not getting lost

but looping

then extending myselfafresh,

starburst,reversing myself

as if turning

to face a partner.

The opening three lines are suggestive. It’s as if someone has closed her eyes to something unpleasant about to happen and has become aware of the dark, unoccupied room behind her eyelids where she may want to hide. The “waiting room” in part two reinforces that feeling. We seem to be in a doctor’s office, or rather the speaker is telling herself or someone else about the visit in a voice no longer sure when this happened or where she was. The poison she’s waiting for sounds like one of those drugs that will either kill you or cure you. It’s been ordered by a “dictator”—no, she corrects herself, by “dictation.” She is going ahead, because the “narrative”—and every life can be called a narrative—makes us anticipate what its next turn may be. The hope is that one will not get lost, but reverse and double upon oneself as if turning to face a partner afresh. I can’t be absolutely sure that this is precisely what she intended, though I suspect it may be one of the ways to read this dark, troubling poem.

Armantrout’s new book, which received the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Pulitzer Prize this year, is her most rewarding. There’s a lot of the “quotidian” in her work, as she herself admits in interviews, and that gives her poems a sense of familiarity. She not only listens to how Americans talk, but she also doesn’t fail to notice the poignant and occasionally comic moments in their lives:

Perfect red roses

coaxed

to frame a doorbeyond which

a couple bickers—and why not?

(from “Perfect”)

Many whisper

white lies

to the dead.“The boys are doing really well.”

(from “Djinn”)

It’s the way that she combines these kinds of wry observations with other found material in what she calls “faux-collages” that creates problems for the reader. Her aim in her poems, Armantrout has said, is to bring the underlying structures of language and thought into consciousness. This sounds promising, until we ask ourselves a few questions: Should a poem that starts so beautifully, as the following one does, undermine its opening image by getting so abstract in its second section?

HEAVEN

1.

It’s a book

full of ghost children,safely dead,

where dead means

hidden,or wanting

or not wantingto be known.

2.

Heaven is symmetric

with respect to rotation.It’s beautiful

when one thing changeswhile another thing

remains the same.

If a single point of view and tone is suspect, how is one to sustain an emotion in a poem? I mean, how does one write a love poem or an elegy if one regards any sort of continuity as untrue to the fragmentary way in which we experience language and consciousness? As far as I’m concerned, it’s the individual parts of her poems that are memorable, and rarely the whole poem.1

3.

Tony Hoagland could hardly be more different from Koethe and Armantrout. Both his new book and his three previous ones, Sweet Ruin (1992), Donkey Gospel (1998), and especially What Narcissism Means to Me (2003), are seriously funny, despite their often not-so-funny subject matter. Hoagland makes room in his poems for both the tragic and the comic view of life, as if leaving out one or the other not only distorts our picture of reality but in the most profound sense fails to tell the truth. This quality of his has less to do with the content of his poems than with their tone. In an essay entitled “Sad Anthropologists,” he defines tone as the speaker’s attitude toward his subject, his audience, or even toward the speaker himself. In that same essay, he defines it further while explaining the kind of poetry he admires:

A poem is a heroic act of integration that binds into rough harmony the chorus of forces within and outside the soul. A poem struggles to orchestrate, prioritize, cohere, and coordinate these potentially shattering forces. A strong poem represents identity without oversimplifying it, and the poem’s internal workings are themselves an analogue of that integrative struggle. That is how tone functions in the dialectical poem.

Born in 1953 in Fort Bragg, North Carolina, Hoagland, the son of an army doctor, grew up on various military bases in the South. He attended and dropped out of several colleges and lived in communes before getting degrees from the University of Iowa and the University of Arizona and becoming a college professor. His poems have a lot to do with his unsettled early life and his suspicion that he, like many of us, is either a tragicomic figure or just a plain old sucker. Like Whitman and, more recently, Allen Ginsberg, his subject is America, which he compares in one of his poems to a disaster movie in which a jumbo jet has gone down in the jungle just as the first-class passengers finished the last of their Chicken Kiev. Life goes on, of course. In another poem, “Big Grab,” the malls are emptying; now even the shoppers who have stopped for a drink are on their way home:

Out on Route 28, the lights blaze all night

on a billboard of a beautiful girl

covered with melted cheese—See how she beckons to the river of late-night cars!

See how the tipsy drivers swerve,

under the breathalyzer moon!

Many of our poets give the impression of driving around blindfolded. That does not necessarily condemn them to irrelevance. There are plenty of interesting things to see with the eyes closed. Besides, isn’t this how we do our remembering and our thinking? Reading Hoagland’s poems is like surfing channels on TV. On one channel they are showing a 1950s sit-com; on another, soldiers are running past burning and overturned cars; on still another, diamonds are being sold at a fabulous discount; there’s a baseball game; a preacher is telling his congregation to consult Jesus on how to invest their money; and so on for hundreds of more channels. All this is beyond comprehension. No wonder there are more poems still being written about pine trees and trout fishing than about teenagers with blue hair, tattoos, and tongue studs.

Here’s a poem from Hoagland’s new book, Unincorporated Persons in the Late Honda Dynasty, that deals with that ignored reality:

FOOD COURT

If you want to talk about America, why not just mention

Jimmy’s Wok and Roll American-Chinese Gourmet Emporium?—

the cloud of steam rising from the bean sprouts and shredded cabbagewhen the oil is sprayed on from a giant plastic bottle

wielded by Ramon, Jimmy’s main employee,

who hates having to wear the sanitary hair netand who thinks the food smells funny?

And the secretaries from the law firm

drifting in from work at noon

to fill the tables of the food court,

in their cotton skirts and oddly sexy running shoes?Why not mention the little grove of palm trees

maintained by the mall corporation

and the splashing fountain beside itand the faint smell of dope-smoke drifting from the men’s room

where two boys from the suburbs

dropped off by their momswith their baggy ghetto pants and skateboards

are getting ready to pronounce their first sentences

in African-American?Oh yes, everything

All chopped up and stirred together

in the big steel pan

held over a medium-high blue flamewhile Jimmy watches

with his practical black eyes.

The main intention of this kind of poem is to liberate us from poetic conventions and at the same time to remind us of what we have avoided looking at closely. “I used to think I was not part of this,/that I could mind my own business and get along,” he writes in another poem, “but that was just another song/that had been taught to me since birth.” “Food Court” cannot be regarded as satire because the speaker in the poem doesn’t place himself above the funny and sad spectacle he’s witnessing. He has too much sympathy to mock any of these people.

This is not the way Hoagland always wrote. His two early books had their comic moments and some good poems, but they lacked the verbal exuberance and visual richness of the last two. Most surely, the influence of Kenneth Koch, Frank O’Hara, Gerald Stern, and younger poets like Dean Young and David Rivard had a part in loosening up his style. Whatever the case, the kind of poems he now writes tend to seem at first like light entertainment and end up being not only serious but genuinely moving:

MY FATHER’S VOCABULARY

In the history of American speech,

he was born between “Dirty Commies” and “Nice tits.”He worked for Uncle Sam,

and married a dizzy gal from Pittsburgh with a mouth on her.I was conceived in the decade

between “Far out” and “Whatever”;at the precise moment when “going all the way”

turned into “getting it on.”…Our last visit took place in the twilight zone of a clinic,

between “feeling no pain” and “catching a buzz.”For that occasion I had carefully prepared

a suitcase full of small talk.—But he was already packed and going backwards,

with the nice tits and the dirty commies,to the small town of his vocabulary,

somewhere outside of Pittsburgh.

There are other poems in Unincorporated Persons in the Late Honda Dynasty written in the same spirit. My favorites are “Plastic,” “Hostess,” “Address to the Beloved,” “The Loneliest Job in the World,” “Visitation,” “Nature,” “The Story of the Father,” and “Voyage.” Hoagland’s poems rarely disappoint because his imagination makes his similes and metaphors not only exhilarating but memorable. “A bird with a cry like a cell phone says something/to a bird which sounds like a manual typewriter” in a poem called “Description.”

It’s not all fun and games, of course, for Hoagland. The undercurrent of even his funniest poems is grim. “Our nation is a career criminal;/we were raised to be liars and deniers,” he writes. In Hoagland’s poems, the United States is not a place that inspires much confidence or hope. He is a poet aware of the hard lives most Americans lead to a degree rarely encountered in contemporary poetry. This is his subject. And so is his sense that something has gone deeply wrong. If the pressure of reality is the determining factor in the artistic character of an era, as well as the determining factor in the artistic character of a person, as Wallace Stevens claimed, Hoagland fits the description. He laments that it had taken him a long time to get the world into his poems. He doesn’t have to worry anymore. It’s all there.

This Issue

June 24, 2010

-

*

Armantrout’s next collection of poems, Money Shot, will be published by Wesleyan University Press in February 2011.

↩