Near the end of his new book, Hitch-22, which is neither strictly a memoir nor quite a political essay but something in between, Christopher Hitchens informs the reader that he has, at long last, learned how to “think for oneself,” implying that he had failed to do so before reaching the riper side of middle age. This may not be the most dramatic way to conclude a life story. Still, thinking for oneself is always a good thing. And, he writes,

the ways in which the conclusion is arrived at may be interesting…just as it is always how people think that counts for much more than what they think.

Like many people who count “Hitch” among their friends, I have watched with a certain degree of dismay how this lifelong champion of left-wing, anti-imperialist causes, this scourge of armed American hubris, this erstwhile booster of Vietcong and Sandinistas, this ex-Trot who delighted in calling his friends and allies “comrades,” ended up as a loud drummer boy for President George W. Bush’s war in Iraq, a tub-thumper for neoconservatism, and a strident American patriot. Paul Wolfowitz, one of the prime movers behind the Iraq war, became his new comrade. Michael Chertoff, head of the Homeland Security Department under Bush, presided over his citizenship ceremony at the Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D.C.

Ah, some will say, with a tolerant chuckle, how typical of Hitch the maverick, Hitch the contrarian: another day, another prank. It is indeed not always easy to take this consummate entertainer entirely seriously, but in this case I think one should. In fact, Hitch’s turn is not the move of a maverick. If eccentricity were all there was to it, his book would still have offered some of the amusement for which he is justly celebrated, but it would have no more relevance than that. Far from being a lone contrarian, however, Hitchens is a follower of a contemporary fashion of sorts. Quite a few former leftists, in Europe as well as the US, have joined the neo- and not so neo-conservatives in the belief that we are engaged in a war of civilizations, that September 11, 2001, is comparable to 1939, that “Islamofascism” is the Nazi threat of our time, and that our shared hour of peril will sort out the heroes from the cowards, the resisters from the collaborators.

There was nothing inherently reprehensible about supporting the violent overthrow of Saddam Hussein, who was after all one of the world’s most monstrous dictators. In this respect, Hitchens had some good company: Adam Michnik, Václav Havel, Michael Ignatieff, to name but a few. It is in the denunciation of those who failed to share his enthusiasm for armed force that Hitchens sounds a little unhinged. He believes that the US State Department was guilty of “disloyalty.” For what? For warning about the consequences of not planning for the aftermath of war? He also claims that the US was subject to a “fantastic, gigantic international campaign of defamation and slander.” He mentions the movie director Oliver Stone, the late Reverend Jerry Falwell, and Gore Vidal. International campaign?

Still, as Hitchens says, it is the “how” that should concern us, not only the “what.” And this is where the memoir is indeed of interest. George Orwell once wrote that he was born in the “lower-upper-middle class,” not grand by any means, better off and better educated than tradesmen, to be sure, but without the social cachet of people who might mix with ease in high metropolitan society. This is the class into which Hitchens was born too, but only just. His father, Commander Hitchens, was a disgruntled naval officer who had had “a good war,” but was retired against his will and reduced to making a modest living as an accountant in a rural school for boys. “The Commander” was a quiet drinker, but by no means a bon viveur—quite the contrary, it seems. His conservatism was resentful, about the end of empire, the end of naval glory, the end of any glory. “We won the war—or did we?” was a staple of his conversation with fellow alte Kämpfer in the less fashionable pubs and golf courses of the English home counties.

Hitchens professes to have much admired the Commander and his wartime exploits, such as sinking the German warship Scharnhorst in 1943: “Sending a Nazi convoy raider to the bottom is a better day’s work than any I have ever done….” Perhaps the young Hitch really did think like that. It certainly informs his current enthusiasm for heroic gestures in the Middle East. But his greatest love was not expended on the Commander, but on his mother, Yvonne, who would have wished to have been a bon viveur in metropolitan society, but was stuck instead in small-town gentility with her peevish husband.

Advertisement

She adored her son, and he clearly adored her. The chapter on his mother is, to my mind, by far the best in the book, because his feelings for her are expressed simply, without sentimentality, and above all without the need to make a point or clinch an argument. Watching a production of The Cherry Orchard one night in Oxford, Hitchens

felt a pang of vicarious identification with the women who would never quite make it to the bright lights of the big city, and who couldn’t even count on the survival of their provincial idyll, either. Oh Yvonne, if there was any justice you should have had the opportunity to enjoy at least one of these, if not both.

If Hitch had one mission in life it was not to be like one of those women.

Yvonne’s end owed more to Strindberg than Chekhov. She broke away from the Commander and took up with an ex-vicar of the Church of England, who had renounced his faith and replaced it with devotion, shared by Yvonne, to the Maharishi Yogi. Together they left for Greece, without saying goodbye to anyone, and were found dead sometime later in a seedy hotel in Athens. Perhaps because they felt that life had failed them, they had decided to die together. Hitchens was devastated. The account of his trip to Athens, at the grisly height of the military junta, is simple, poignant, personal, and sounds right.

This, however, is not the end of Yvonne’s story. Years later, in 1987, Hitchens’s grandmother revealed that her daughter had harbored a secret. She, grandmother Hickman, also known as “Dodo,” was Jewish. Perhaps Yvonne was afraid that this information might not have gone down well at the Commander’s golf clubs. Her son, however, was rather pleased by the news. Hitchens’s great friend Martin Amis declared: “Hitch, I find that I am a little envious of you.” Quite why having a Jewish grandmother should provoke envy is not made entirely clear. But Hitchens, following strict rabbinical rules, feels that he qualifies as “a member of the tribe.” He then revives the old-fashioned notion that Jews have special “characteristics,” which interestingly coincide with ones he accords to himself: cosmopolitanism, of the rootless kind, sensitivity to the suffering of others, devotion to secularism, even a penchant for Marxism. I’m not sure who is being flattered more: Hitch or the Jews.

Long before he was aware of having inherited Jewish characteristics, politics entered his life. Hitchens was educated at a respectable private institution, named the Leys School, in Cambridge. Politics at this establishment for the lower-upper and upper-middle classes were suitably Tory. Hitchens quite enjoyed his schooldays and gives an amusing, even appreciative account of them. It was then, however, in the mid-1960s, that the “exotic name” of Vietnam began to dominate the evening news. He was shocked by what he heard about this war, and when the British government refused to withhold support for “the amazingly coarse and thuggish-looking president who was prosecuting it,” he, Christopher Hitchens, began “to experience a furious disillusionment with ‘conventional’ politics.” He continues: “A bit young to be so cynical and so superior, you may think. My reply is that you should fucking well have been there, and felt it for yourself.”

To which one might well reply: Been where? Cambridge? And why the sudden hectoring tone? Clearly, even then, doubt would never get a look in once a cause was adopted. With his brother, Peter, who is now a rather ferocious conservative journalist of some note in England, Hitchens went off to demonstrate against the war in Trafalgar Square, donning “the universal symbol of peace” in his lapel with “its broken cross or imploring-outstretched-arm logo.” Here, too, a pattern was set. I did not know Hitchens in those days, but ever since I met him in London in the 1980s, I’ve never seen him without a badge in his lapel for one cause or another.

Protesting against the Vietnam War was not a bad thing to do, of course. But still sticking to the business of how rather than what Hitchens thinks, the peculiar tone of self-righteousness, combined with a parochial point of view, even when the causes concern faraway, even exotic countries, is distinctive. After leaving the Leys School, Hitchens enrolled as an undergraduate at Balliol College, Oxford. Introduced to the ideas of Leon Trotsky by his brother Peter, he joined a tiny group of revolutionaries named the International Socialists, or IS. Peter, by all accounts, was the hard man, the enforcer of the right ideological line. Hitchens was too much of a hedonist to be a truly convincing hard man. He was prone to flirtation with, among other gentlemen, a college warden with an eye for pretty boys, who would invite him to the more exclusive Oxford high tables.1

Advertisement

IS had about one hundred members, but, Hitchens writes, had “an influence well beyond our size.” The reason for this, it seems, was that “we were the only ones to see 1968 coming: I mean really coming.” Again the self-referential choice of words is remarkable. Not the students in Prague, Paris, Mexico City, or Tokyo, not even the Red Guards in Beijing—no, it was the members of the International Socialists at Oxford who really read the times.

A more charming (though for some readers perhaps rather cloying) byproduct of this concentration on small bands of loyal comrades is Hitchens’s near adulation of his friends, all famous in their own right. Martin Amis, James Fenton, and Salman Rushdie merit chapters of their own. So does Edward Said, but he fell out of favor after September 11, as did Gore Vidal, whose gushing blurb on the back cover of the book has been crossed out. I’m not sure whether the fondly recalled examples of Amis’s linguistic brilliance do his best friend any favors. Calling the men at a grand black-tie ball “Tuxed fucks” is mildly amusing, but a sign of “genius at this sort of thing” it surely is not. In any case, these tributes are clearly heartfelt.

Perhaps a tendency toward adulation and loathing comes naturally with the weakness for great causes. Politicians and people Hitchens disapproves of are never simply mentioned by name; it is always the “habitual and professional liar Clinton,” “the pious born-again creep Jimmy Carter,” Nixon’s “indescribably loathsome deputy Henry Kissinger,” the “subhuman character” Jorge Videla,2 and so on. What this suggests is that to Hitchens politics is essentially a matter of character. Politicians do bad things, because they are bad men. The idea that good men can do terrible things (even for good reasons), and bad men good things, does not enter into this particular moral universe.

By the same token, people Hitchens admires are “moral titans,” such as the Trinidadian writer C.L.R. James. Not only was James a moral titan, but he was blessed with a “wonderfully sonorous voice.” He also had “legendary success with women (all of it gallant and consensual, unlike that of some other masters of the platform).” This is a dig at President Clinton, whom Hitchens habitually calls a “rapist.” Why he should know how James, or indeed Clinton, behaved in the sack isn’t explained. But bad sexual habits are clearly a sign of bad politics. For many years Gore Vidal was a “comrade,” worshiped by Hitchens as much as Rushdie et al. But now that he has taken the wrong line on Iraq and September 11, we have to be told that Vidal “always liked to boast that he has never knowingly or intentionally gratified any of his partners.” Well, that puts paid to him. Hitchens reassures us four pages later that whatever followed from his own meeting with Martin Amis, it “was the most heterosexual relationship that one young man could conceivably have with another.” Good for Hitchens and Amis.

Another typical word in Hitchens’s lexicon is “intoxication.” This can literally mean drunk. But that is not what Hitchens means. Writing about his early political awakening, when he shared with his fellow International Socialists a “consciousness of rectitude,” he claims:

If you have never yourself had the experience of feeling that you are yoked to the great steam engine of history, then allow me to inform you that the conviction is a very intoxicating one.

This must be true. When Hitchens became a journalist for the New Statesman, after graduating from Oxford, he adopted a pleasing kind of double life, part reporter, part revolutionary activist, imagining how he might help an IRA terrorist hide from the law. He found this double life “more than just figuratively intoxicating.” One can only assume that intoxication again played a part when he took the view that yoking himself to George W. Bush’s war was to hitch a ride on the great steam engine of history.

The trouble with intoxication, figurative or not, is that it stands in the way of reason. It simplifies things too much, as does seeing the world in terms of heroes and villains. Or, indeed, the dogmatic notion that all religion is bad, and secularism always on the right side of history. One of the weaknesses of the chapter on Hitchens’s journalistic exploits in Poland, Portugal, Argentina, and other places is that he never seems to be anywhere for very long or meet anyone who is not either a hero, someone very famous, or a villain. One longs to hear the voice of an ordinary Pole, Argentinian, Kurd, or Iraqi. Instead we get Adam Michnik, Jorge Luis Borges, Ahmad Chalabi, all interesting people, but rather exceptional ones. One misses all areas of gray, all sense and variety of how life is lived by most people.

In some countries, most people are religious. A consequence of the constant sneering about religion, of any kind, is that it obscures political analysis. What should we think, for example, of the persecution of religious parties in Middle Eastern police states? Must we stand with secular dictatorships in Egypt and Syria just because they are opposed by the Muslim Brotherhood? Was a military coup in Algeria justified only because Islamists won democratic elections in 1991? There is no simple answer to any of these questions. But atheistic sloganeering does not help.

Hitchens seems to be perfectly well aware of this. He writes in his concluding chapter:

The usual duty of the “intellectual” is to argue for complexity and to insist that phenomena in the world of ideas should not be sloganized or reduced to easily repeated formulae. But there is another responsibility, to say that some things are simple and ought not to be obfuscated….3

He is right. Standing up to Nazism or Stalinism was the only decent thing to do in the last century. There are turning points in history when there can be no ambiguity: 1939 was such a year, and for Communists perhaps 1956. The question is how Hitchens came to the conviction that 2001 was such a time. The mass murder perpetrated in Lower Manhattan, Virginia, and Pennsylvania by Osama bin Laden and his terrorist gang must be strongly condemned. Nor do I have a quarrel with the claim that Saddam Hussein’s “state machine was modeled on the precedents of both National Socialism and Stalinism, to say nothing of Al Capone.” But the idea that September 11 was anything like 1939, when Hitler’s armies were about to sweep across Europe, is fanciful.

For Hitchens, however, it seems to have brought back the specter of the Commander. He quotes W.H. Auden’s poem “September 1, 1939,” when “Defenseless under the night/Our world in stupor lies….” He recalls Orwell’s essay, entitled “My Country Right or Left,” written in 1940, when Hitler was at his most menacing. And he thunders: “I don’t know so much about ‘defenseless.’ Some of us will vow to defend it, or help the defenders.” He decides that the US is “My country after all” (his italics). He realizes that “a whole new terrain of struggle had just opened up in front of me.” Acquiring US citizenship at the Jefferson Memorial may not be quite on the same order as sinking the Scharnhorst, but it was one way to contribute to the War on Terror, I guess.

In fact, as Hitchens writes, his break with the old left on the question of US military interventions came earlier, in the Balkans. In Bosnia, he writes, “I was brought to the abrupt admission that, if the majority of my former friends got their way about nonintervention, there would be another genocide on European soil.” I, for one, agreed with that sentiment then and still do. Still, Iraq in 2003 was not Bosnia in the early 1990s. Saddam Hussein had certainly been guilty of mass murder in the past, and would have had no scruples to be a killer again, but the Iraq war was not launched to stop genocide. It was sold to the public as a necessary defense against a tyrant’s acquisitions of nuclear weapons, and a strike against the men who, as was quite falsely alleged, helped to bring the Twin Towers down. Liberal hawks and neocons, as well as some hopeful (or desperate) Iraqi liberals, were more sold on the idea of liberation and democracy, but officially that was an afterthought. If a democracy cannot make up its mind precisely why it needs to start a war, it is surely better not to start one in the first place.

Weapons of mass destruction did not clinch the argument for Hitchens. For even if it could have been proved that Saddam had none, he writes, “I would have argued—did in fact argue—that this made it the perfect time to hit him ruthlessly and conclusively.” Since 2001, in the mind of Hitchens, was like 1939, he skates over any distinction between Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden, and talks blithely about “the Saddamist–Al Qaeda alliance.” So keen was he to be among the liberators, and so attracted to the heroic gesture, that both his moral compass and his journalistic instincts began to seriously let him down.

In an earlier phase of his career, Hitchens tells us, “I resolved to try and resist in my own life the jaded reaction that makes one coarsened to the ugly habits of power.” Quite right too. He was also commendably staunch about the use of torture by the British in Northern Ireland. A Labour minister who defended torture as a necessary measure is called “a bullying dwarf.” Hitchens writes: “Everybody knows the creepy excuses that are always involved here: ‘terrorism’ must be stopped, lives are at stake, the ‘ticking bomb’ must be intercepted.” What on earth was this same Hitchens thinking, then, when he adopted Donald Rumsfeld’s deputy, Paul Wolfowitz, as his new good friend?

Hitchens was so smitten with George W. Bush’s Pentagon, despite its connivance at torture, that he appears to have believed everything he was told: “In all my discussions with Wolfowitz and his people at the Pentagon, I never heard anything alarmist on the WMD issue.” To be sure, Wolfowitz has since admitted that oil was a major reason for going to war, and the threat of WMDs was just a convenient “bureaucratic” excuse. But his Pentagon boss certainly was alarmist about the nuclear threat, as were the President and the Vice President. In claiming that there was no alarmism at the Pentagon, Hitchens is either disingenuous or a lousy reporter.

He appears to want it both ways, however. On the one hand, WMDs didn’t matter, and on the other he wants us to believe that they were indeed a threat, and what is more, that he, Hitchens, found proof of this. UN inspectors under Hans Blix looked at five hundred sites in Iraq without coming up with any evidence of WMDs before they were recalled. But Hitchens dismisses these as “very feeble ‘inspections.'” Blix must have been very feeble indeed, for Hitchens, on one trip to Baghdad, in the company of Paul Wolfowitz, was shown components of a gas centrifuge dug up from the back garden of Saddam’s chief physicist. And he was told by the US Defense Department that “some of the ingredients of a chemical weapon” had been found under a mosque.

That is not all. Before the war a band of comrades, including Ahmad Chalabi—a slippery political operator with strong links to Iran—was taken up by Hitchens, this time with the rather grandiose name the Committee for the Liberation of Iraq. It was “the combination of influences” of this group “by which political Washington was eventually persuaded that Iraq should be helped into a post-Saddam era, if necessary by force.” And this group of heroes, according to Hitchens, was subjected to a “near-unbelievable deluge of abusive and calumnious dreck….” This unbelievable deluge was dropped, no doubt, by the kind of “Western liberals” whose “sick relativism…permitted them to regard ‘honor’ killings and genital mutilation as expressions of cultural diversity.”4 Not to mention liberals like “Norman Mailer, John Updike, and even Susan Sontag,” who all “appeared to be petrified of being caught on the same side as a Republican president.”

Again, the narcissism, the narrow scale of characters, and the parochial perspective are startling: “We were the only ones to see 1968 coming.” It is as if the central focus of the Iraq war was about scores to be settled between Hitchens and Noam Chomsky or Edward Said. It is odd that in all his lengthy accounts of the war, the name of Dick Cheney is mentioned only once (because he happened to share the same dentist with Hitchens). What is utterly missing is a sense of perspective, and of the two qualities Hitchens claims to prize above all: skepticism and irony. A skeptic would not answer the question whether he blamed his former leftist friends for criticizing the war with: “Yes, absolutely. I was right, and they were wrong, that’s pretty much it in a nutshell.” Asked about his literary influences, Hitchens mentioned Arthur Koestler. He was right on the mark. Koestler, too, lurched from cause to cause, always with the same unshakable conviction.5

How, then, does Christopher Hitchens think? Several times in the book he expresses his loathing of fanaticism, especially religious fanaticism, which in his account is a tautology. As a typical example he cites the Japanese suicide pilots at the end of World War II. In fact, many were not so much fanatical as in despair about a corrupt society going under in a catastrophic war. But if modern Japanese history must serve as a guide to our own times, Hitchens might have mentioned a different category of misguided figures: the often Marxist or formerly Marxist intellectuals who sincerely believed that Japan was duty-bound to go to war to liberate Asia from wicked Western capitalism and imperialism. They saw 1941 as their finest hour, the moment when men were separated from boys, when principle had to be defended, when those who didn’t share their militancy were disloyal weaklings. These journalists, academics, politicians, and writers were not all emperor-worshipers or Shintoists, but they were believers nonetheless. The man who emerges from this memoir is a bit like them: clearly intelligent, often principled, and often deeply wrongheaded, but above all, a man of faith.

This Issue

July 15, 2010

What Obama Should Have Said to BP

-

1

These flirtations elicit the odd remark that he has a special sympathy for women, because he knows “what it’s like to be the recipient of unwanted or even coercive approaches….” This, I feel, underrates the seductive appeal of the habitual charmer.

↩ -

2

Not that the Argentine junta leader was not guilty of horrendous crimes, but even criminals, alas, are human.

↩ -

3

This dilemma explains the title of the book, Hitch-22.

↩ -

4

If you look for them carefully, especially in universities, you might still find some people who think like that, but I would hesitate to call them liberals.

↩ -

5

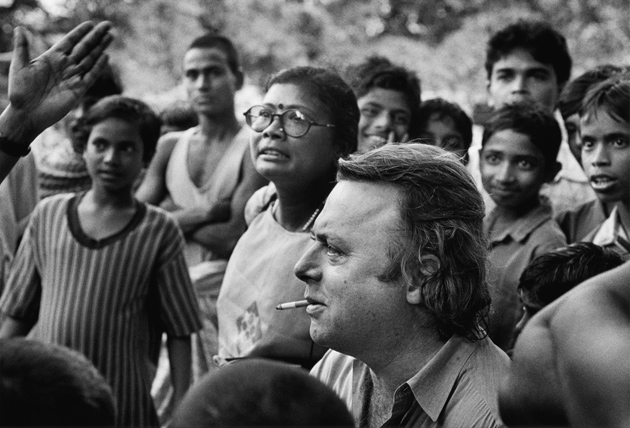

Perhaps “liberating Iraq,” the caption to a photograph of Hitchens smoking a cigarette with delighted Iraqis, is meant to be ironical. Somehow, I doubt it.

↩