Can we make any sense of Israel’s policy toward Gaza? I think we can—a rather sinister sense—but only if we look beyond the mass of sometimes conflicting details that have emerged since the attack on the “Gaza Freedom Flotilla” on May 31. On the face of it, it’s hard to understand how any government could have decided to do anything so obviously self-defeating. At the very least Israel has handed Hamas a major propaganda victory, one that should easily have been foreseen. On the other hand, there is surely something about the whole foolish, deadly episode that is emblematic of Israeli’s current approach. Listen, first, to the public statements.

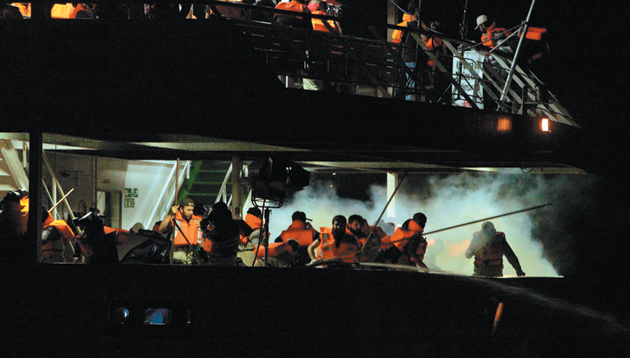

“Everything would have worked fine, but the passengers reacted inappropriately.” Thus, a headline describing the reaction of the captain who led the Israeli naval commando team onto the Mavi Marmara—the Turkish ship that was attempting to bring humanitarian aid to Gaza as part of the flotilla—and who was wounded in the ensuing struggle. (He was said to be speaking from his hospital bed.) He is certainly not alone in taking this view of the incident. In his first public statement after the debacle, Defense Minister Ehud Barak also blamed the activists on board the Turkish ship for what happened; he later added, in a striking non sequitur, that in the Middle East you cannot afford to show weakness, though that is precisely what the Israeli attack had demonstrated. Spokesmen for both the army and the government repeatedly said that the soldiers were in danger of being lynched—as if they were innocent victims of an ambush rather than, in effect, state-sponsored pirates attacking a convoy carrying humanitarian aid in international waters. The Israeli genius for “designer victimhood,” to borrow a phrase from the Indian political philosopher Jyotirmaya Sharma, is capable of surprising flashes of ingenuity.

Within a week, the activists on the Mavi Marmara who resisted the attack had been upgraded in Israeli public discourse to terrorists—an amazingly capacious category that sometimes seems to include anyone who refuses to toe the government line. Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman had applied the term to the flotilla activists indiscriminately, even before the boats set sail. But it’s important to emphasize that the violence by some of the activists on the Turkish boat against the Israeli commandos contradicts the basic tenets that the Israeli peace movement has embraced for many years. Those of us who work in the occupied Palestinian territories have been attacked many times, sometimes savagely, by Israeli settlers, and sometimes by soldiers and police; we do not meet violence with violence.

Such was not the case on the Mavi Marmara. Perhaps there were, indeed, hostile Islamic fundamentalists aboard the ship, as the government claims. But this is hardly the point. These boats were carrying medicines, wheelchairs, cement, and other badly needed items, not weapons. Despite the contorted rationalizations put forward by government spokesmen, including Israel’s ambassador to the United States, Michael Oren, the decision to mount a military attack on the flotilla is, to put it simply, indefensible on moral grounds. Moreover, aside from the moral considerations, which—contrary to popular opinion in Israel—are crucial to any meaningful reckoning, the long-term damage to Israel’s interests, especially its strategic ties to Turkey, is apparent for all to see.

It’s also worth noting that at the critical meeting of Cabinet ministers who made the decision, the Cabinet secretary, Zwi Hauser, advocated that the boats simply be allowed through—as indeed has happened several times before, notably with the first Free Gaza sea convoy in August 2008, with the well-known Israeli peace activist Jeff Halper aboard.1 Hauser’s voice went unheeded; the ministers unanimously voted for the mission.2 The unanimity is impressive; it suggests to me that Israel is governed by people who are not merely incompetent but who are only tenuously in touch with the real world. Even more frightening is the thought that large parts of the electorate have by now been affected by this delusional state.

It’s hardly a secret that the blockade of Gaza is ineffective. The lively trade through tunnels dug between Gaza and Sinai supplies whatever people can pay for, including missiles and other weapons for the Hamas government and the other militant groups. But not everyone can pay. The impoverished population of Gaza (approximately 1.5 million people crammed together in one of the densest concentrations on earth) suffers from severe shortages of some items—in particular, basic building materials such as glass and cement3:—and, of course, from the results of the vast destruction the Israeli army left behind after Operation Cast Lead in December 2008–January 2009.4 The blockade is meant to isolate and punish—and, in the most optimistic Israeli scenario, to bring down—the Hamas government, and possibly to “persuade” Hamas to release the kidnapped soldier Gilad Shalit; its main effect, however, has been to isolate and punish the blockaders.

Advertisement

Why, then, maintain the siege? And why turn a harmless convoy of activists into an existential threat, as the prime minister and other government spokesmen have repeatedly done? No doubt there are considerations of prestige and “honor,” in the common Middle Eastern sense of wounded, hence fanatical and ultimately self-destructive, pride. But I think the blindness goes much deeper than this. We are observing unmistakable signs of “multiple systems failure,” the direct result, in my view, of four decades of occupation. The very nature and future of Israel’s society and political system are at stake, and the danger of collapse into a repressive regime run by the secret security forces is very great. Many of us would say that the line was crossed long ago.

It is important to understand the depth of the change that Israel has undergone since the present government came to power in the spring of 2009. Netanyahu heads a government composed largely of settlers and their hard-core supporters on the right. Their policy toward Palestine and Palestinians rests upon two foundations: first, the prolongation, indeed, further entrenchment, of the occupation, with the primary aim of absorbing more and more Palestinian land into Israel—a process we see advancing literally hour by hour and day by day in the West Bank. Second, there is the attempt to control the Palestinian civilian population by forcing them into fenced-off and discontinuous enclaves. Gaza is the biggest and most volatile of the latter, and it is the only one, so far, to have put a Hamas government in power; but if the political situation in the West Bank continues to worsen, or if the deadlock continues, it is likely that Gaza will not be the last such place.

Maintaining the occupation is, of course, incompatible with making peace, and indeed it should be clear by now to all that the present Israeli leadership has no interest in resolving the conflict. Quite the contrary: the ongoing proximity talks with the Palestinian Authority are no more than a diversion. I know of no one in Israel who takes them seriously, least of all the Netanyahu government. Gaza itself provides another helpful distraction. The very idea of peace based on mutuality, compromise, and at least minimal respect for the dignity of the other side is anathema to the men and women in the Cabinet who are making the decisions.

There is another critical facet to the shift that has taken place. Under conditions of escalating nationalist hysteria, Israeli dissent is harshly dealt with. Ezra Nawi, one of the heroes of Israeli nonviolent resistance to the occupation, is now in jail. (He was convicted of assaulting a policeman while protesting the demolition of houses in South Hebron, although there is excellent evidence, including video footage, showing Ezra acting in the classic mode of Gandhian-style nonviolent resistance on that day.) The determined protestors against the evictions of Palestinians from their homes in Sheikh Jarrah, in East Jerusalem, are constantly being arrested and rearrested (meanwhile, another two large Palestinian families there have received eviction notices); leaders of the Israeli Arab community, such as Knesset member Ahmad Tibi, have received death threats and are routinely harassed by the security forces.

The villages of Bil’in and Na’alin, where nonviolent protest against the route of the security fence was pioneered and has continued without interruption for over four years, are now a closed military zone, off limits to Israeli peace activists. More important still is the attempt to break the back of nonviolent grassroots protest in Palestine by arresting and sometimes prosecuting, on trumped-up charges, the leading activists in the villages to the south and west of Jerusalem; someone has clearly identified this mode of resistance as a serious threat to the occupation. At least some of the items on this list may be explained by the fact that internal security is now in the hands of the ultra-right party Yisrael Beitenu, which has given us Foreign Minister Lieberman (he also, of course, voted to attack the flotilla).

What happened on the open seas on May 31 was thus no technical mishap or simple operational failure, as many Israelis would like to believe; nor was it only a function of the obvious inability on the part of the decision-makers to distinguish illusory or trivial goals from genuine Israeli interests (turning back a convoy carrying wheelchairs was never one of the latter). Rather, it expresses in a profound way the narrow, mean-hearted vision of an atavistic nationalism coupled with a delight in the fantasy of unrestricted coercion.

Advertisement

By far the best solution to the problem of Hamas rule in Gaza would be to cut a deal with the moderate, responsible, and by now increasingly effective Palestinian leadership in Ramallah. Such an agreement, built on Israeli withdrawal to the Green Line and the evacuation of the settlements, would put an end to the overtly colonial enterprise on the West Bank, which is incompatible with basic democratic values and human rights. All careful studies show that a large majority of Palestinians in both the West Bank and Gaza would support such an agreement, which would in all probability undermine Hamas’s attempts to retain power in Gaza or to expand its power to the West Bank.5 Instead, the Israeli right prefers to indulge in displays of impotent and self-righteous fury, as happened on the Mavi Marmara.

Israel’s few remaining friends in the world clearly see that the blockade is counterproductive and must end. After his meeting with Mahmoud Abbas on June 9, President Obama suggested that the blockade should be lifted on everything except arms shipments. “The status quo that we have is…inherently unstable,” he said. In one of his first statements as prime minister, David Cameron told the British Parliament, “Friends of Israel…should be saying to the Israelis that the blockade actually strengthens Hamas’s grip on the economy and on Gaza and it’s in their own interests to lift it and to allow these vital supplies to get through.” But the Israeli government is no less clearly committed to continuing, thus compounding, its errors. Indeed, perhaps “errors” is too pale a word for the deep conceptual and spiritual malaise that shapes Israel’s Palestinian policy today.

Time is running out, possibly has already run out, for a solution based on partition. Still, there are occasional flashes of something slightly new. On June 2, Moshe Arens, former minister of defense in three Likud governments and a prominent spokesman for the right (in my view, the extreme right), published a column in Haaretz arguing that an Israeli retreat from the West Bank and the evacuation of settlements are inconceivable; along with various figures on the left, such as Meron Benvenisti, the former deputy mayor of Jerusalem, he thinks that the so-called two-state solution is long dead, a chimera kept alive artificially by the leadership on both sides in order to paste over the disastrous reality on the ground. But Arens’s surprising conclusion is that because the occupation is irreversible, the Palestinian population on the West Bank—some 1.5 million by his count, probably a little low—should be granted Israeli citizenship and integrated into the Israeli state. Note that Arens has intentionally left out the 1.5 million Palestinians languishing in Gaza.

There have also been recent reports of small groups of Israeli settlers in the territories who have come to the conclusion that the current situation cannot endure, and that new modes of coexistence are called for. There are, it appears, points where the far right and the far left of the Israeli spectrum might coincide; perhaps these are the points where change will begin. In the meantime, some ten thousand Israelis have demonstrated in Tel Aviv against the siege of Gaza, and the blockade continues in full force.

—June 16, 2010

This Issue

July 15, 2010

What Obama Should Have Said to BP

-

1

Halper was arrested as soon as he reentered Israel from Gaza.

↩ -

2

There is now some controversy over the exact number of ministers present at the meeting. Initially, it was reported that the core group of seven “security ministers” were all there. But following satirical attacks in the press by commentators such as Yossi Sarid, who spoke of the “seven idiots,” at least one of these ministers has reportedly tried to dissociate himself from the decision by claiming he wasn’t there and is, therefore, ipso facto, no idiot.

↩ -

3

The list of items banned by Israel, which changes from month to month, is a truly astonishing work of bureaucratic creativity. Is there any logic to preventing the import of cilantro and flowers into Gaza? For figures on the working of the blockade, see my [“Gaza and the Israeli Peace Movement: One Year Later,”](http://www.nybooks.com/blogs/nyrblog/2010/jan/04/gaza-the-israeli-peace-movement-one-year-later/) NYR Blog, January 4, 2010.

↩ -

4

The supply of electric power has not recovered from the damage caused by the military campaign, with the result that most families have to face power cuts of from eight to twelve hours a day. Clean drinking water is rarely available. The infrastructure of health services has been devastated. The WHO reports that 10 percent of the population now suffer from chronic malnutrition.

↩ -

5

See, for example, the latest surveys of Palestinian public opinion by the highly respected Khalil Shikaki and Nabil Kukali, of the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research and the Palestinian Center for Public Opinion, respectively.

↩