Twenty-five years ago, when I was twenty-eight and trying to write a novel, I sent this fan letter to John Updike. I lived in Brookline, Massachusetts, back then, and my girlfriend, now my wife, lived in Boston. I printed the letter out all on one page, with narrow margins, using my new Kaypro computer and Juki daisywheel printer. Updike didn’t answer—he couldn’t, because I didn’t put a return address on the envelope.

3/10/85 12:06pm

Dear Mr. Updike:

I read three quarters of your “Constellation of Events” just now on a nice, sunny Sunday morning subway ride on the D line, having borrowed that New Yorker from my girlfriend, and, having to stop in the middle of your story and get out and walk home, I had a thought, being still under the oddly peaceful emotional umbrella of your story: I had it, in fact, just walking under the awning of a tuxedo shop: I thought what an amazing thing that Mr. Updike has been writing all the years that I have been growing up, and how I have come to depend on the idea that he is writing away as a soothing idea, and then I was reminded of Trollope, and how nice it must have been for writers back then to go about their lives knowing that Mr. Trollope was going to have a new book coming out soon, that it would be good; and they might not read all of the things he wrote, but they would read some, and they would know that what they didn’t read they were missing, but were comforted also that they knew what kind of man he was because they had already read a lot of what he wrote; and the idea they had of the man who gradually had written all these books was a powerful, happy thing in their lives.

I thought this because I had just read a charitable review by you of a book I probably will never read by Andre Dubus, and this had made me go through the pile of magazines to find your story, which my girlfriend had mentioned: there was something wonderful about having this story of yours waiting there, in a wicker basket of magazines, indifferent to whether I read it or not, yet written by a writer whose personality and changes of mood I felt I had some idea of in a way you can only have of a writer who has written a great deal, lots of which you have forgotten, only retaining a feeling of long-term fondness which is perhaps the most important residual emotion of the experience of literature. And I thought all this in a second, pleased with myself, and then, as I passed out from under the brief shade of the tuxedo shop awning and diagonally crossed Route 9, I thought that you probably had written all this in some other book review or essay that I hadn’t read, or had read and forgotten; and this pleased me too, because after all it is a simple thought, mostly compounded of gratefulness and the pleasure that Sunday mornings have, and the good thing about Mr. Updike is that he is a true writer, and writes out the contents of his mind, and that idea occurred to him once, no doubt, suggested by some book he was reviewing, and he wrote it down; and that was what being a man of letters was all about. This subsiding feeling took me to my doorstep, where I remembered a passage from John Jay Chapman, which I will now look up and quote:

Your complete literary man writes all the time. It wakes him in the morning to write, it exercises him to write, it rests him to write. Writing is to him a visit from a friend, a cup of tea, a game of cards, a walk in the country, a warm bath, an after-dinner nap, a hot Scotch before bed, and the sleep that follows it. Your complete literary chap is a writing animal; and when he dies he leaves a cocoon as large as a haystack, in which every breath he has drawn is recorded in writing.

“Balzac,” quoted in Richard B. Hovey, John Jay Chapman

Now that I have quoted it, I’m not sure how it applies, but it does seem to nest with the rest a little.

So, thank you for inspiring this chain of pleasurable emotions on a Sunday. Now I’ll go finish your story.

Very truly yours,

Nicholson Baker

12:48pm (interruptions)

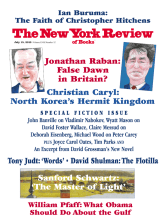

This Issue

July 15, 2010

What Obama Should Have Said to BP