The early-nineteenth-century Danish artist Christen Købke wasn’t the first or the last painter to record the subtlest effects of light. But at his current traveling retrospective, which I saw at the National Gallery in London—it is the first extensive show of his work ever held outside his homeland—a viewer could believe that few other artists have shown the way light can settle on the thinnest edges of forms, or glow from within a face, or suffuse atmosphere itself, with quite the same delicacy and firmness. And what makes this Danish painter’s presentation of light particularly distinctive is that it doesn’t feel virtuosic or calculating. He makes it seem, rather, as if there existed a source of light within his pictures and he were gently bringing it to the surface—and as if in the next moment the light we see could lose its intensity.

Købke, who was born in 1810 and died in 1848, was largely forgotten after his death, but he has now long been considered Denmark’s finest painter. At his peak in the 1830s when he was in his twenties, he was something of a perennial student, ever testing himself on how best to structure a given composition or how finely to balance the tones of his colors. In the course of testing himself he made a good many jewel-like and psychologically astute portraits and a number of both sparkling and muted, and in either case tautly composed, views of locations in and around his native Copenhagen.

He painted scenes of people in rooms or outdoors and gave his attention to sites as august as Frederiksborg Castle, an imposing Renaissance palace outside the city, and as lowly as a local seaside lime kiln. He went from subject to subject in seemingly the most unprogrammatic, even serendipitous, way, and his body of work is not large. Yet taken together, his pictures, graced by sudden appearances of enchantingly unexpected colors—whitened pink lake waters, purple skies enveloping red bridges—give a sense that we have encountered a complete little world.

Købke is a figure whose precise importance keeps shifting as he is thought about. On the one hand, he is almost a model of the modest artist. His pictures are often small in size and generally include areas that are so finely detailed that we need and want to get very close. His art certainly has little of the sweep or sense of life being reimagined before our eyes that we encounter in the work of artists whose careers overlapped his in time, whether Ingres, Delacroix, Caspar David Friedrich, Turner, or Constable.

Købke’s paintings, which form, essentially, a record of family and friends and of places he lived in or near or (so it feels) explored on this or that afternoon, convey no sense of myth, dreams, or foreboding, or of any forces beyond our control. The artist, whose letters present someone who struggled with his Christian belief and sweated out the making of his pictures (and suffered continual digestive disorders), probably would not have understood the sense of heroism his grander contemporaries saw in their roles as artists or attached to the very endeavor of painting.

Yet his best pictures present a pressing, unremitting need to do justice to the presence, or character, of the person whose portrait he was making—or to the conditions of light and depth in the scene before him—and it makes him come across as a fairly fierce and commanding creator. And while he wasn’t an idea-driven person, his work touches on some of the leading intellectual and artistic currents of the time. In his predilection for a careful realism and for making an art about the people and the life he knew intimately, he could be said to epitomize the Biedermeier spirit. Yet unlike most artists linked with this style (which reflected a conservative reaction to political and social unrest), Købke was something of a painting engineer.

There is an overall spare, uncluttered, even flinty look to his pictures, making him far more of a Neoclassicist than a painter of bourgeois comfiness. His feeling for formal order certainly leaves no room for the piety and good cheer that coat a lot of Biedermeier art. Classically structured as many of his paintings are, however, Købke was on some level also a Romantic. The Romantic’s vaunted feeling for the artist as a person who sees more deeply than the rest of us is unmistakable in a powerful self-portrait from 1833, where he looks out in a spirit both troubled and resolved.

The very outline of Købke’s life, moreover, has a touch of the fevered energy we associate with Romanticism. A mature artist by age twenty, he found himself run aground—locked in a fruitless struggle with uncongenial material—even before he was thirty. This condition lasted for the rest of his short life. All the work of his that matters to us was done by the time he was twenty-eight. And while his art doesn’t revolve around childhood in itself—a precinct of naturalness and wisdom for many artists and writers connected with Romanticism—it does spring from a sense of well-being derived from his family milieu.

Advertisement

Until the current exhibition, Christen Købke has been seen outside Denmark principally in shows—including one in 1984 in London and another that visited Los Angeles and New York in 1993 and 1994—of what has been called the Golden Age of Danish painting. This was an era, stretching over a few decades in the first half of the nineteenth century, when the Danes, their economy and political fortunes having taken severe hits in the Napoleonic era (they backed Napoleon), were inching their way toward financial and social stability. Perhaps because Danish society had recently had its foundations shaken and remained incompletely mended, a number of its writers and thinkers became set on defining a national identity, and there was a concomitant flowering of activity in the arts. The country’s best-known writers, Søren Kierkegaard and Hans Christian Andersen, were active at the moment, as was its foremost choreographer, August Bournonville, while theologians and poets of the era such as N.F.S. Grundtvig and Adam Oehlenschläger were then reaching a considerable audience.

At the same time, an influx of very young men wanting to be painters was met, at Copenhagen’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts, by the right man for the job. This was C.W. Eckersberg, a strong if ultimately earthbound painter who instilled not only a feeling for classical poise and balance—he had studied in Paris with Jacques-Louis David—but the concept, novel at the time in the European art academies, that a painter could profitably work outdoors, directly from nature. Even more crucial, Eckersberg imparted the thought, which Købke clearly took to heart, that everything and anything could be a suitable subject for a painter.

Artists with charm and real flair emerged from Eckersberg’s tutelage, capable of delicate nature studies and delicate views of streets and yards. But the lack of an audience prosperous enough to invest meaningfully in artworks helped keep Copenhagen’s renaissance a fledgling one. On top of that, the three most gifted painters of this generation—Købke, Wilhelm Bendz (a live wire whose interior scenes are still engaging), and Johan Thomas Lundbye (an inventive and stylish landscapist)—all died young.

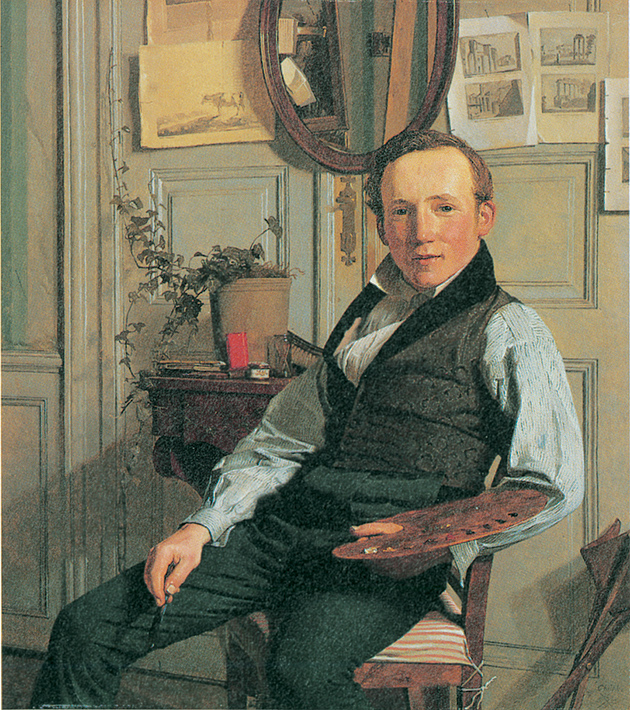

The most immediately beckoning aspect of Købke’s work is probably his portraiture. The picture that drew me to the artist (about whom I wrote an introductory study in 1992) was his portrait of a landscape painter named Frederik Sødring. It is somehow both an adorable and magnificent picture. Measuring some 16 inches high by 14 inches wide, it is hardly grand as an object; and the image, which is that of a smiling, smartly dressed young man (or boy, almost), whom we see slouching easily on a chair, his legs spread open, a palette in one hand and a palette knife in the other, broadcasts the genial opposite of magnificence. Yet the work’s spirit of friendliness and ingenuousness is rarely seen so nakedly and convincingly in a painting. What makes the portrait momentous (and probably the artist’s most reproduced work) is the way that, looking at it, we are given the uncanny sensation of having walked into the culture of the time.

Sødring is in his studio, and Købke’s rendering of the textures of his sitter’s skin and clothes and the many aspects of the small bit of the room behind him are so optically accurate and sensuously appealing as to affect us hypnotically. The work’s subtly dynamic composition, with its circular and angled, and centered and off-centered, elements, comes to a climax in the way the painting, whose colors are made up of the sitter’s flesh tones and many pleasingly related shades of mostly grays and blues, has near its center a little red box.

To spend any time before this sunny work is to fall in love a little with Sødring himself and to wish that Købke had made more portraits where he shows us a bit of his sitter’s milieu. As it happened, he generally put his sitters before monochrome backgrounds, or at most a suggestion of a room. Yet his grasp of the individual temperaments of the people who sat for him was so sharp that, as we encounter some of Købke’s other portraits, Frederik Sødring soon becomes merely one of a string of people whom we think we know intimately and generally feel drawn to.

Advertisement

Not that Købke’s cast of characters is reliably friendly. There are glum and testy sitters; and while the naval officer D. Christen Schifter Feilberg, who is seen in uniform, putting on a glove, doesn’t stand before us with an exactly imperious expression, he does make us want to keep our distance. Købke here appears to have caught the moment before a sneer (or a withering smile?) sets in. The part of the painting where Feilberg tightens the fit of his glove with his free hand wittily echoes the subtly admonitory expression on his face.

As a work of art, though, we can hardly keep any distance from Feilberg’s portrait. The way the artist has set little zones of bright, distinct red, yellow gold, and white against a soft, receding gray and different blues, and the way Feilberg’s face and the silhouette shape of his uniform play against these spots of color, make for a picture whose parts keep moving as we look at it. The painting shows a person of some apparent hauteur. Yet Købke, with his split-second capturing of an expression in the making, also suggests that we see someone who might be uncertain about his feelings, and this results in a psychological complexity that Ingres didn’t have. It is Ingres, of course, who lodges in our minds when we look at this and other Købke portraits. We are left wondering just what the great French portraitist would have felt about a twentysomething from practically nowhere who, though not making literally grand, imposing paintings, was in some ways his match.

Happily, both the Sødring and Feilberg portraits are part of Købke’s retrospective. Organized by David Jackson, who also wrote its sensitive and perceptive catalog, the show contains the essence of the artist, though people who have seen and loved his art in Denmark, where the majority of his pictures are in public collections, may feel the lack of a number of strong works. (I did.) The cramped and awkwardly disjointed space the exhibition occupied in the London National Gallery, which necessitated that a number of the artist’s smaller pictures be hung one above the other, didn’t help, either. Double hanging is particularly unfortunate in Købke’s case because some of his highly compressed pictures are in truth considerable works. The museum’s putting, for instance, the tiny portrait of Ida Thiele, which is roughly 9 inches high by 8 inches wide, beneath another work practically forfeited the presence of one of Købke’s remarkable paintings.

Here is an image of an eighteen-month-old child that has about it little of the obvious sweetness the subject might be expected to produce. Nor is it weighed down by the otherworldly oddness that the German Romantic painter Philipp Otto Runge, another of Købke’s near contemporaries and a specialist in children, would have found in it. Besides not condescending to this very young person, Købke has made a work where his almost mechanistic ability to define forms with razor-sharp contours was hardly ever bettered. His feeling for color was rarely more audacious, either. Showing us a blonde-haired little girl in a raspberry-red dress before a uniform lavender background, Ida Thiele is arguably as memorable an image of a child as any school of art has produced.

That none of Købke’s drawings (which are in pencil) are part of the exhibition is unfortunate as well. These often masterful works take the form of densely detailed portraits and airier, more purely linear drawings of courtyards, say, or pathways, and their presence is badly missed. This is particularly the case with the portraits. They can make anyone who responds to the many different soft gray tones a lead pencil is capable of become dizzy with pleasure.

Yet enough of Købke’s work is in the show to give a sense of his accomplishment. If not all his pictures (particularly the larger ones) hold us the way the small portraits do, it is probably because they lack a needed quotient of minuscule detail, or a sense that light has been made part of the scene in a whisper-soft yet energizing way. When there isn’t any of this almost literal fine tuning, the pictures don’t feel like Købkes at all. They seem dormant or anonymous.

For American eyes, Købke’s best early pictures are like previews of the work Winslow Homer and Thomas Eakins would be doing some decades later, in their own early (and perhaps best) work. Købke, too, is naturalistically showing a kind of classless, backyard, pastoral-suburban world—and one that misses being humdrum because the artist handles his material with a formalist’s exactitude. Taking in his images of an entrance to a little bridge, with some boys hanging around it, or of a girl walking on a ramp up to a storehouse, or simply of leafy walkways through grass, with sailing ships in the distance, we are engaged because, as with Eakins’s pictures of boatsmen and bird hunters, these pictures are less about local color than the quest of an artist who obsessively wants to achieve the proper spatial alignment of everything within his image.

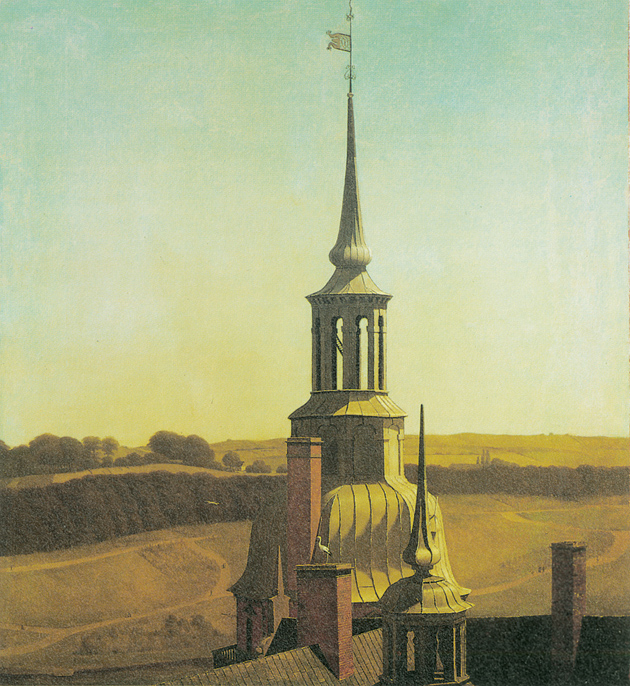

In Købke’s later views of Frederiksborg Castle, which he caught from different vantage points, his spirit became more expansive. His subject was one of the largest palaces in northern Europe. And he shows it so informally—as when tourists are seen wandering about or, in their top hats, rowing in little boats in the surrounding water—that the building becomes alive to us in a way that historical edifices in paintings rarely do. By the time he was at work on them, the artist and his family had moved to a large house on Lake Sortedam, then considered part of the new suburbs just outside Copenhagen. For the dining room there, Købke created a suite of paintings that included two large pictures of the roof at Frederiksborg, and in these works (one of which made it to the London show) he surpassed himself.

Nearly six feet on a side and spookily almost devoid of any dramatic interest, these paintings of rooftops, seen against cloudless, strikingly empty skies, may not have any real counterparts in all of European art at the time. Some artists in those years (particularly the not widely known but often engaging German painter Eduard Gaertner) were making vaguely similar rooftop scenes for the panoramas that were then popular. But paintings for panoramas were generally smaller in size than these Købkes, and they existed to give presumably enticing information about the site being surveyed. Købke, instead, gives an unusual sense of sheer Romantic aloneness. We are with someone who has gotten up to a roof at a quiet moment on a summer’s day and there witnessed an unimportant yet, for a visual person, thrilling event: sunlight landing on the thin edges of the metal sheathing of a steeple. It would be sixty or seventy years before other artists conceived of making such large works about such stilled moments. Even now the rooftop pictures feel like extraordinary anomalies.

Not long thereafter, Købke’s Danish career, and a crucial part of his inner life, came to an end. In 1838, heeding the call that beckoned so many Scandinavian and German artists in these years, he took off for an extended stay in Italy where, over a period of about two years, he made oil sketches and drawings in Rome, Naples, and Capri. Back in Copenhagen in 1840, he and his wife Sanne, whom he had married before leaving, proceeded to have two children (and, with their own new family, continued living in his parents’ house). And in the last eight years of his life he made a few portraits of family and friends and a number of oil sketches of clouds and of the lakeside house before it had to be sold.

His chief labor, though, went into turning his Italian sketches into finished compositions. But the Italian work, from those first little pictures on, lacked the drive, necessity, and sense of continual experimentation that marked his earlier painting. Even when he crisply shows light falling on a rocky coastline or a classical column, these pictures lack the flavor of a particular artist. Købke himself seems to have been aware of this. He kept postponing the delivery to the Royal Academy of the large Italian picture, a view of a site on Capri, that would give him his diploma and make him an academician. When he turned it in six years after his return from Italy, it was rejected. It was thought by family members—David Jackson writes—that the blow, combined with pneumonia, is what caused his death, a few months short of his thirty-eighth birthday.

Købke’s story has a crushing second half, yet in some way his collapse is understandable. One can almost feel that the Købke who worked at a blue streak in the 1830s was a person who operated with the thought that everything he did was part of an extended preparation for the day when his real career would begin—and in the course of his preparation used up his material. A few aspects of this Købke, in any event, give the impression of someone who was easily as involved in his home life as he was with his position in the art world of the day. In addition to many of his pictures being directly bound to his own experiences, he was reluctant at first to enter works in competitions, and he gave away numbers of his paintings as gifts. The portrait of Sødring was simply a birthday present to the sitter.

If he felt trapped by his Italian material after he returned, the issue may have involved more than his not knowing what to do with his sketches of Capri, or his inability to take up Danish subjects with real intensity again. The issue may have been that, having given so much of himself to an endeavor that clearly was a kind of extension of his family life, he froze when confronted with the prospect of launching out entirely on his own.

David Jackson wants us to believe that all was not lost. He sees a restored Købke in his various later pictures of the family’s house and in a large portrait of a relative named Ryder, done in the months before the painter’s death. For Jackson, this image of a beefy fellow is as strong a portrait as the artist made. But the picture, which is part of the exhibition, is to my eyes a shocking reminder that Købke had lost everything that made him distinctive. The portrait, which could be by any nineteenth-century journeyman painter anywhere, is entirely devoid of the incisive feeling for form, light, and character that gives Købke his urgency.

Jackson’s desire to see Købke intact at the end, though, is very understandable. He is an artist we feel unusually close to personally. Everything about him is transparent and pure. When he lost his step, he lost it entirely. But it does him no service to say that he regained his power, especially since he made his own conclusive statement about the work of his that counts. It is in the form of three modestly sized lakeside paintings from 1838, the year he left Denmark.

In these wonderfully ambiguous pictures, set at different times of the year and of the day, he shows people by water who might be thinking of departures. But the prevailing mood of the scenes is, by a hair, more one of conclusions. Without a touch of pathos (and with none of the symbology of Caspar David Friedrich, whose scenes they vaguely recall), Købke found three separate ways to suggest the ends of things—of an afternoon, of a season, of an outing on a lake. He had never before made pictures of such emotional depth. The best known of the three, View from the Embankment of Lake Sortedam, Looking Toward Nørrebro, showing women on a little dock, watching a distant boat, is the one that has been included in the present show. All three, however, are perfect in their way, and it would be good to see them together one day.

This Issue

July 15, 2010

What Obama Should Have Said to BP