1.

The two Koreas are entering a dangerous new phase in their tortuous relationship. In a speech on May 24, South Korean President Lee Myung Bak suspended trade relations with Pyongyang, barred Northern vessels from passing through South Korean waters, and promised immediate retaliation for any North Korean incursions into the South’s territory by land, sea, or air. The North Koreans responded by denouncing Lee as a “traitor” and a “bastard” and announced that they would answer any Southern military moves with “all-out war.” A North Korean battlefield commander vowed to open fire on South Korean loudspeakers if the government in Seoul attempted to resume long-dormant propaganda broadcasts across the Demilitarized Zone. Since President Lee’s speech the North’s all-powerful leader, Kim Jong Il, has vanished from public view—as he has been wont to do in the past whenever he had reason to fear becoming the target of laser-guided munitions used by the South’s army and its US allies.

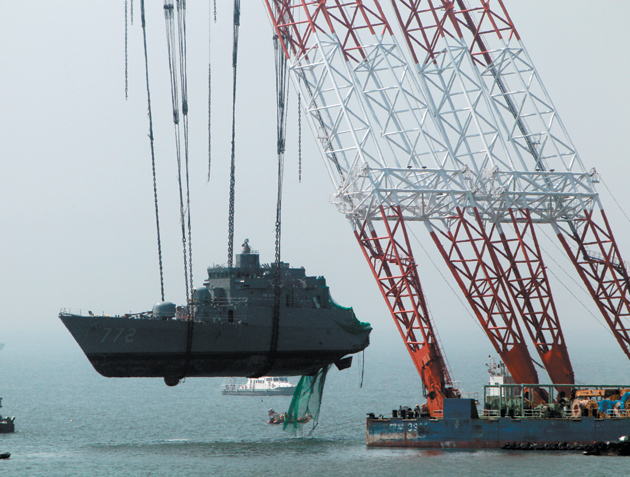

The proximate cause of this spike of mutual antagonism dates to the last week of March, when a mysterious explosion struck a South Korean naval vessel called the Cheonan. The ship was on patrol near the Northern Limit Line, a maritime border that was unilaterally declared by the South in the wake of the Korean War in 1953 but has never been recognized by Pyongyang. The blast ripped the ship in two, sending both halves to the bottom of the sea and taking the lives of forty-six sailors. Under the circumstances, Lee acted with remarkable restraint. He appointed a multinational commission to examine the incident and gave it all the time and resources it needed to get the job done properly.

Finally, some seven weeks after the explosion, the panel presented its conclusions. The evidence the investigators presented included fragments of a torpedo that had been dredged from the sea floor near the spot where pieces of the Cheonan had also been raised. The torpedo was consistent with a type known to have been sold by Pyongyang to other countries and bore a Korean marking. The investigators also noted that a North Korean naval task force, including several small submarines of a type that could have attacked the ship, had set out from port a few days before the attack and returned a few days later.1

Though based on circumstantial evidence, this is about as powerful a case as one might expect to see marshaled in a court of law. The investigators’ careful forensic work has made it clear that the sinking can be attributed only to hostile action; and North Korea is the only state in the region to have both the means and the motive to carry out such an action. One of the details of Pyongyang’s response was particularly revealing. Buried amid the torrent of invective was an overture: the North declared itself prepared to send its own group of investigators to Seoul to review the evidence. That offer, as of this writing, has not been accepted.

2.

The one question that remains unanswered, of course, is precisely why the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) would have dared to commit an act described by several observers as the most serious military provocation since the end of the Korean War. How the government in Seoul—as well as its US ally—chooses to answer this question will have a great deal to do with the subsequent development of events. Some analysts have speculated that the attack on the Cheonan was retaliation for a firefight that took place in the fall of 2009, when South Korean naval forces, after the usual warnings, opened fire on a North Korean ship that entered Southern waters. The North Koreans were repulsed, perhaps with some casualties. But such minor skirmishes have taken place again and again over the years. Why should the North Koreans have chosen such a disproportionate response this time around?

It is true that the sinking of the Cheonan is merely the latest installment in a long history of North Korean surprise attacks and terrorist operations. Over the decades Pyongyang has repeatedly infiltrated commandos into the South by land and sea. In 1968, a team of North Korean special forces, on an apparent mission to assassinate then president Park Chung Hee, managed to get within a few hundred yards of the Blue House in Seoul, the seat of the South’s government, before they were stopped.2 The North has also killed members of the South Korean Cabinet in a bomb attack, blown a South Korean airliner out of the sky, kidnapped South Korean citizens, and conducted assassinations on the South’s territory.

Advertisement

Just this past spring the government in Seoul announced that it had uncovered a plot by Pyongyang’s agents to kill a high-ranking defector who has been on Kim’s hit list for years. While such incidents have certainly deepened North Korea’s status as a pariah nation, neither Pyongyang nor Seoul is particularly eager to resort to open warfare; the South knows that its own economy would suffer incalculable devastation, and the North knows that the highly trained and well-equipped South Korean military, backed by the imposing arsenal of the US, would win any prolonged conflict. For many years the overriding pressures against war have coexisted uneasily with the North’s habit of periodically ratcheting up tensions as a way of blackmailing other powers into offering it aid or diplomatic concessions.3

But it would be wrong to see the latest tensions merely as the prolongation of a nerve-racking but essentially stable status quo. Something fundamental has changed. Today North Korea is approaching a decisive moment in its history as a state—one that greatly magnifies the risks for governments that hope to cope with the consequences. North Korea watchers are speaking of a “tipping point,” fraught with vast ramifications for the entire region.4

To some extent, of course, we have heard this before. After the collapse of the Communist system in Eastern Europe in 1989–1991 many onlookers predicted the end of the DPRK—which, in the event, proved astoundingly durable. Yet this time around there are two clear reasons why the Kim Family Regime (as many Korea watchers in the US military tend to refer to it) finds itself confronting a situation of exceptional volatility. The first has to do with Kim Jong Il himself. The continuity of any despotic system depends disproportionately on the well-being of the person at its center, and North Korea has concentrated power in its leader to a degree unparalleled in the contemporary world. In 2008 the outside world learned that the Dear Leader had suffered a debilitating stroke. During a visit to China this spring, the once-pudgy sixty-nine-year-old Kim looked ravaged and gaunt; lately there have also been rumors of his having kidney disease.

Kim has compounded the sense of uncertainty by long holding off on appointing a successor. Only recently, it would seem, has he ordered the state apparatus to begin enshrining his third son, a twenty-something by the name of Kim Jong Un, as his likely heir. But that is no simple matter. Though little is known about the future Kim the Third, his relative youth means that he is drastically inexperienced in matters of state. Even if he ascends to the throne as planned, it is likely that he would prove little more than a figurehead, opening up the possibility of factional rivalry and instability. On June 7, Kim named his brother-in-law Jang Song Taek—who had been purged just a few years ago for reasons that remain unclear—to the number two position in the regime, a move that most experts saw as part of Kim’s effort to manage the transition.

This crisis within the leadership overlaps with a second, broader trend within the country at large. Over the past decade and a half North Korea has undergone a revolutionary transformation. At the beginning of this process it was still a nation largely closed to the rest of the world, its people subject to an intricate web of social controls organized around a bizarre official mythology. The DPRK of 2010 is a place where many people have achieved a small but crucial measure of power over their own lives and have learned enough about the outside world to understand the fundamentally flawed nature of their own system.

The best account of this evolution available so far is Barbara Demick’s Nothing to Envy, a minutely reported collective portrait of six North Korean lives based on extensive interviews with defectors from the same industrial city of Chongjin. Through her subjects we relive the economic turmoil set off by the disappearance of the Soviet empire in the early 1990s, followed, in the middle of that decade, by a largely man-made famine that took the lives of anywhere from 2 to 10 percent of the population. This slow-motion economic collapse brought down the state’s food rationing and distribution systems and made survival dependent on a radically new set of skills. Rank-and-file North Koreans responded by creating a parallel private economy, offering everything from homemade noodles to bicycle repair services.

Demick, a reporter with the Los Angeles Times, doesn’t just tell us about this process; instead, in a tour de force of meticulous reporting, we experience it up close, in all its scruffy particulars. Through her witnesses she carefully documents an entire country’s shift backward to a preindustrial past:

In Chongjin, the hulking factories along the waterfront looked like a wall of rust, their smokestacks lined up like the bars of a prison. The smokestacks were the most reliable indicators. On most days, only a few spat out smoke from their furnaces. You could count the distinct puffs of smoke—one, two, at most three—and see that the heartbeat of the city was fading. The main gates of the factories were now coiled shut with chains and padlocks—that is, if the locks hadn’t been spirited away by the thieves who had already dismantled and removed the machinery….

In summer, hollyhocks crept up the sides of concrete walls. Even the garbage was gone.

Workers leave the motionless factories to forage in the countryside. Lights flicker, then go off. Salaries dwindle and gradually disappear. Just as the infrastructure seizes up, so too does the accustomed social order. In the old days, the defectors tell Demick, “people knew what the rules were and which lines not to cross. Now the rules were in play—and life became disorderly and frightening.”

Advertisement

The gap between the regime’s histrionic propaganda and the ever-deepening brutalization of everyday life widens until it becomes impossible to ignore. Disillusionment comes to each of Demick’s subjects in different ways. For Jun-Sang, a privileged young intellectual, it is access to restricted foreign literature—including a book on Russian economic reform, of all things—that sows his initial doubts. He begins to tune in furtively to South Korean television broadcasts. One day, amid the horrors of the famine, he hears a starving urchin singing a paean to the glories of the leadership—and something snaps:

[Jun-sang] would later credit the boy with pushing him over the edge. He now knew for sure that he didn’t believe. It was an enormous moment of self-revelation, like deciding one was an atheist.

Demick’s choice of religious terminology here is no accident; for many Northerners, the official worldview has long served as a kind of ersatz religion. Now, with a jolt, they find themselves sliding into apostasy.

For a young schoolteacher, the awakening comes as she watches the children in her class sicken from malnutrition and gradually die. For an apolitical, middle-aged woman who has just watched her husband and son expire from hunger, it comes with the simple act of firing up a homemade stove to bake cookies for illegal sale in the local private market—a decision that requires “unlearning a lifetime of propaganda.”

For Dr. Kim, a self-described “patriot,” the moment of final disenchantment turns on the accidental discovery that her socially undesirable background has made her a figure of suspicion to the Party she has believed in all her life. A secret policeman—from the National Security Agency (or Bowibu), one of several overlapping organizations of its kind in the North—warns her not to commit treason by crossing the relatively open border to China: “The more she thought about it, the more that the Bowibu man’s [implied] reasoning made sense. He had planted the idea and she found she couldn’t shake it.” Once in China she happens upon a plate of food lying in a farmer’s courtyard. At first she can’t figure out why anyone would leave such bounty unguarded:

Up until that moment, a part of her had hoped that China would be just as poor as North Korea. She still wanted to believe that her country was the best place in the world. The beliefs that she had cherished for a lifetime would be vindicated. But now she couldn’t deny what was staring her plainly in the face: dogs in China ate better than doctors in North Korea.

China is not only a destination for those seeking a better life. It is also the source of a flood of new goods to North Korea:

Writing paper, pens and pencils, fragrant shampoos, hairbrushes, nail clippers, razor blades, batteries, cigarette lighters, umbrellas, toy cars, socks. It had been so long since North Korea could manufacture anything that the ordinary had become extraordinary.

Some of those goods transform consciousness more overtly. Soon there is a booming black market in contraband movies and music—much of it shipped secretly from South Korea. North Koreans’ favorite films soon included Titanic, Con Air, and Witness; they also marvel at South Korean soap operas, which frequently impart startling details about everyday life in the “village down there” (as Northerners refer to the South). One man recalls catching a radio broadcast of a South Korean sit-com that involved two women feuding over a parking space: “He couldn’t grasp the concept of a place with so many cars that there was no room to park them.”

Not even the Communist Party remains unaffected. As Kongdan Oh and Ralph Hassig note in their informative book, The Hidden People of North Korea, the apparatchiks are soon holding lectures warning that North Korea could go the way of the Warsaw Pact if Party functionaries can’t stem the corrosive effects of entertainment from the outside world. Not even the functionaries themselves are immune: “Even bureaucrats in the Central Party organizations are said to be ‘infected with capitalist germs.'”

The lecturers exhort the security forces to redouble their efforts to crack down on illicit video-viewing. (North Korean law provides for a four-year sentence to labor camp for those who are found guilty of this offense.) But no one should neglect the most important countermeasure of all: North Koreans, according to the regime’s spokesmen, must “firmly equip [themselves] with the respected and beloved general’s revolutionary ideology.” As the authors note, this seems particularly ironic in light of the fact that Kim Jong Il himself is known to be an avid consumer of foreign movies and luxury foodstuffs imported from abroad. In an earlier day such demoralizing contradictions would have never made their way outside of the tiny privileged circle around the Great General. Increasingly, though, this too can no longer be taken as a given.

3.

When North Korea’s leaders say something, they like to be sure that their people are listening; outsiders are not invited to participate. Every public building, every home, every place where North Koreans live and work has its own set of loudspeakers connected by cable to a central transmitter. Unlike conventional television and radio, this closed network—known as the “third broadcasting system”—has the advantage that it is very hard to monitor from outside of the country. Hence the Pyongyang regime often uses this medium to communicate its most important decisions to the populace.

On the morning of Monday, November 30, 2009, the speakers crackled into life. In a special announcement, the government informed its citizens that, in the days to come, they would be expected to exchange their old banknotes for new ones. Taking into account years of inflation, all denominations in the new currency would be reduced by a factor of one hundred, and all prices would be adjusted correspondingly. So far, so good. Other countries have performed simple redenomination of their currencies before and, handled properly, such measures can make life easier for people in countries where inflation has left businesses and consumers juggling long strings of zeroes.

As soon became apparent, however, what the authorities meant by this new “currency reform” was something rather different. Not only did the government impose this fiat on its people with virtually no warning at all, but it also set a ceiling on the amount of old currency that could be exchanged for the new. This was not simply a redenomination; it was a confiscation.

The aim was clear. The DPRK’s leadership had tolerated the proliferation of private markets, and of an ever-widening sphere of economic activity outside of the state’s power, long enough. Now it was intervening to take away the savings built up by North Korea’s army of small entrepreneurs.

What happened next amounts to a striking departure from sixty years of DPRK history. As always, it is hard to verify the details, given the near impossibility of independent reporting inside the country. It is clear, nonetheless, that ordinary North Koreans immediately expressed their anger at the government’s move—in some cases publicly.5 A man burned his personal hoard of old banknotes in an open protest. Stall owners at a private market—one of many that have sprung up around North Korea in the wake of the famine-induced economic collapse in the mid-1990s—closed for the day in an impromptu demonstration. Security forces are said to have staged a number of public executions to quell building unrest. (None of this will come as a complete surprise to readers of Demick’s book. Before publishing she managed to include accounts of similar protests predating the currency reform—including a particularly vocal one against the local authorities’ attempt to shut down the especially large market in Chongjin itself.)

Perhaps even more astoundingly, the North Korean government subsequently felt compelled to address the discontent. A few weeks after the initial announcement came the news that the state had decided to raise the cap on the amount that people could exchange. Not long after that, the regime’s number two man sent out a circular to regional Communist Party officials in which he apologized for the policy’s ineffective implementation. (To be sure, he didn’t apologize for the measure itself, and the North Korean people at large have yet to hear any expressions of remorse from their leaders.) Then, in March, South Korea’s Yonhap news agency reported that the bureaucrat in charge of the “currency reform” had been shot.

Still, the basic measure has been allowed to stand, and the entirely predictable effects have become manifest. Goods are being hoarded, prices have shot up, and anyone with the opportunity has rushed to exchange their won into Chinese renminbi or other foreign currencies. Video footage smuggled out of the North shows once-bustling markets that now stand deserted.6

If you believe that the North Korean leadership views China’s example of authoritarian market reform as a perfectly reasonable model of development, you would have a hard time explaining why the government in Pyongyang would resort to such patently self-destructive measures. In The Cleanest Race, B.R. Myers offers a possible answer: North Korea’s leaders actually take their ideology seriously—and this, he insists, is one reason why the regime has managed to hang on for so much longer than its Eastern European counterparts.

In his brilliant and provocative book Myers manages to do away with several generations’ worth of inherited misperceptions about the North Korean regime. As he shows, for all its claims to adherence to Marxism-Leninism, North Korea has actually followed a rather distinct brand of exclusionary racialism modeled closely on the mystical nationalism of Hirohito’s imperial Japan. (Myers isn’t just speculating here; he shows that several of the key architects of North Korean ideology actually worked in the Japanese propaganda apparatus in the period from 1910 to 1945, when Korea was a Japanese colony.) East German diplomats stationed in Pyongyang in the 1950s and 1960s sent cables to Berlin in which they overtly compared the reigning ideology in North Korea with Nazism.

As Myers sees it, this brand of radical identity politics has enormous staying power. Much of Marxism-Leninism’s appeal derived from its claims to greater economic efficiency, so the East Bloc’s obvious failure to keep pace with the supposedly inferior capitalist West did much to undermine the legitimacy of the Soviet-style Communist model. By contrast, North Korean officials are relatively relaxed about admitting that South Koreans are richer.7 Those Southerners may be wealthy, goes the argument, but they are spiritually impoverished, leading lives of deracinated decadence under the brutal rule of the Yankee imperialists and their crass, alien culture. As a result, all Southerners long for the day when they can once again be unified under the inspired leadership of Kim Jong Il, that embodiment of unsullied Korean virtues.

In some sense, Myers shows, this claim to represent the pure, the “authentic” Korea—along with its clutch of nuclear weapons—is really all the North has left to offer. It is correspondingly hard to imagine why Pyongyang would ever want to give that up: “As if the poorer Korea could trade a heroic nationalist mission for mere economic growth without its subjects opting for immediate absorption by the rival state!”

Myers does overreach at times. He notes that the overwhelming majority of the hundreds of thousands of North Koreans who have crossed the border into China ultimately return to their homeland, and he attributes this to the enormous persuasive force of the regime’s worldview. An even better explanation might be plain old unglamorous fear—fear of the unstinting violence with which the regime treats the extended families of those known to have defected to the South. (The East German state that allowed millions of its own citizens to flee to the West was incomparably softer on the relatives who stayed behind.)

Yet Myers is certainly right to say that what he calls “the erosion of the information cordon” strikes a potentially fatal blow to the coherence of “the Text,” his shorthand for the official belief system. As the Northerners learn more, it is increasingly seeping through that Southerners are happy with their own republic, that they could not care less about Kim Jong Il and regard most Northerners as backward primitives, and that most are not terribly keen on the idea of reunification, which is likely to be enormously messy and expensive. “There is just no way for the Text to make sense of this highly subversive truth,” he concludes.

So how does a North Korea shorn of its justifying myth go on? One way might be by rallying society around the threat of an external enemy—which is why we should not be entirely surprised to see other Cheonan-style provocations in the months ahead. Aside from that, though, it increasingly appears as if the only glue left to hold the Kim Family Regime together is brute force. Yet the recent public disturbances over the revaluation of the currency suggest that some North Koreans appear to be gradually overcoming their fear of the state. Can Kim Jong Il and his family maintain their hold for a few more years? Perhaps. But it is clear by now that something fundamental has changed, and that there can be no going back to business as usual.

Despite its wrathful posturings, North Korea is not a state in control of its own destiny. Much will depend in the weeks to come on the position of the DPRK’s prime protector, China. So far Beijing has shown little inclination to risk its alliance with Kim Jong Il by condemning him for the attack on the Cheonan. Meanwhile the government in Seoul faces the difficult job of devising a policy that will satisfactorily straddle the conflicting demands of its own electorate, for both protection against the North and recognition of ethnic brotherhood with it. One can only hope that the people of the North, so long the victims of machinations beyond their control, will manage to evade the next catastrophe-in-waiting.

—June 16, 2010

This Issue

July 15, 2010

What Obama Should Have Said to BP

-

1

American intelligence agencies have leaked some additional incriminating details. According to them, shortly after the Cheonan sinking Kim Jong Il visited the unit responsible for carrying out special operations. Kim commended the unit for recent actions on behalf of the nation and gave its commander a promotion.

↩ -

2

The memory of this particular attack remains vivid there, as I recently saw during my own visit to the president’s residence this spring. Here and there, on the immaculate grounds, one comes across military vehicles with mounted machine guns.

↩ -

3

See, for example, Joshua Keating, [“Was the North Korean Crisis All Talk?”](http://blog.foreignpolicy.com/jkeating) Passport Foreign Policy‘s blog, June 2, 2010.

↩ -

4

Marcus Noland, “Pyongyang Tipping Point,” The Wall Street Journal, April 12, 2010.

↩ -

5

See, in particular, Stephen Haggard and Marcus Noland, [“The Winter of Their Discontent: Pyongyang Attacks the Market,”](http://www.iie.com/publications/pb/pb10-01.pdf) Peterson Institute for International Economics . See also Blaine Harden, “In North Korea, a Strong Movement Recoils at Kim Jong Il’s Attempt to Limit Wealth,” The Washington Post, December 27, 2009.

↩ -

6

For a copy of the video (with English subtitles), see [“Rare Footage Shows Impact of Botched N. Korean Reform,”](http://english.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2010/04/22/2010042200391.html) The Chosun Ilbo, June 9, 2010. A link to the video can be found at the bottom of the page.

↩ -

7

I can vouch for him on this one. My own North Korean minders freely admitted the same on one of my own visits to the North in 2007. The explained their country’s relative poverty with the “economic blockade” imposed on them by the West (and, above all, the United States). They then hastened to add that North Koreans were unquestionably superior to their Southern cousins in spiritual terms, thanks to the “the splendid leadership of the great general Kim Jong Il.”

↩