“I admit that I saw in America more than America,” Tocqueville wrote: “J’avoue que dans l’Amérique j’ai vu plus que l’Amérique.” He saw less than America too, in certain ways. He saw the image of a survivable democracy and a lesson for the rumbling, leveling future of Europe. But he also thought that democracy and America were different things, and objected to those who “confuse what is democratic with what is only American.” The cultural darkness of 1830s America as he viewed it (“the Americans have not yet, properly speaking, got any literature,” he wrote, and he didn’t think things looked good for the sciences or the fine arts either) was part of a particular history, not a measure of possibility; a fact about a democracy, not about democracy. There is a discreet touch of Anglophobia here since Tocqueville regards “the people of the United States” as “that portion of the English people whose fate it is to explore the forests of the New World…. I do not think the intervening ocean really separates America from Europe.” Certainly not as much as the Channel, otherwise known as La Manche, separates England from France.

Tocqueville gives a graphic account, in a letter, of all the things he believes America hasn’t got:

They have neither wars, nor plagues, nor literature, nor eloquence, nor revolutions, nor fine arts, nor many great crimes—nothing of what excites attention in Europe.1

This sounds like a mixed bag of things to do without, and we hear the flickering irony in the list’s discrepancies. Indeed, we almost hear an anticipation of Henry James’s ironic tabulation of American lacks in his 1879 book on Hawthorne:

No State, in the European sense of the word, and indeed barely a specific national name. No sovereign, no court, no personal loyalty, no aristocracy, no church, no clergy, no army, no diplomatic service, no country gentlemen, no palaces, no castles, nor manors, nor old country-houses, nor parsonages, nor thatched cottages, nor ivied ruins; no cathedrals, nor abbeys, nor little Norman churches; no great Universities nor public schools—no Oxford, nor Eton, nor Harrow; no literature, no novels, no museums, no pictures, no political society, no sporting class—no Epsom nor Ascot!

James is writing of “American life…forty years ago”—this would take us back to 1839, some eight years after Tocqueville’s journey, and four years after the publication of the first part of Democracy in America. We spot the mischief in James’s parade—with a tiny handful of exceptions, every absence begins to look either desirable (no sovereign) or trivial (no thatch)—and this picture of desolation might be taken as a backhanded compliment. This is just where James is going, in the slyest possible way. “The natural remark,” he continues,

in the almost lurid light of such an indictment, would be that if these things are left out, everything is left out. The American knows that a good deal remains; what it is that remains—that is his secret, his joke, as one may say.

What remains is everything that is missed by people who think they know what everything is.

Peter Carey’s inventive, zigzagging novel Parrot and Olivier in America is chiefly set in just this America, a place of great physical beauty, eccentrically ambitious people, and social institutions that are both stolid and skimpy. The book “began,” Carey says, when he read Tocqueville, and he invites us to find Tocqueville’s own words “squirreled away among the thatch of sentences”—no relation at all to the thatch there isn’t in America. He also describes his own work as “very fanciful,” and the notion of fancy is important here, especially in an old and continuing sense the Oxford English Dictionary gives us: “We know matters of fact by the help of…impressions made upon phansy.” We could take this as a way of thinking about the American’s joke or secret.

Carey’s leading character Olivier de Garmont lives a good chunk of Alexis de Tocqueville’s life, but he is not Tocqueville for several excellent reasons, quite apart from his being fictional. He travels to America not with an aristocratic French friend but with an English servant called Parrot; he almost marries the daughter of a Connecticut grandee; he composes pieces of his book in the new world, which Tocqueville did not; and above all, the person we get to know under the name of Olivier could not have written Democracy in America—he has the wit and the energy and the nerves but he doesn’t have the logic or the gift for the grand abstraction. The fact that Tocqueville himself couldn’t write his book until he had spent four years back in France becoming the Tocqueville we know complicates this distinction but doesn’t erase it.

Advertisement

Olivier is a jumpy, snobbish, sickly fellow whom his servant calls Lord Migraine, and his angle on the world makes up only half of Carey’s novel. Well, to be precise, although this precision is not confirmed for us until the very last page, his angle on the world is not the angle it seems. It turns out that Olivier’s English servant, John Larrit alias Parrot, has not only written his own half of the text, like Esther Summerson in Dickens’s Bleak House, but has conjured up Olivier as well. His farewell to us and his master, which he calls his “Dedication,” is a tour de force of suggestion and complication.

Larrit insists that Olivier was wrong to fear the tyranny of the majority in America, as he and Tocqueville so anxiously did. “Your fears are phantoms,” Larrit firmly says.

Look, it is daylight. There are no sansculottes, nor will there ever be again. There is no tyranny in America, nor ever could be…. The great ignoramus will not be elected. The illiterate will never rule. Your bleak certainty that there can be no art in a democracy is unsupported by the truth.

“You are wrong, dear sir,” Larrit continues, “and the proof that you are wrong is here, in my jumbled life, for I was your servant and became your friend.”

I was your employee and am now truly your progenitor, by which I mean that you were honestly MADE IN NEW YORK by a footman and a rogue. I mean that all these words, these blemishes and tears, this darkness, this unreliable history…was cobbled together by me, jumped-up John Larrit, at Harlem Heights, and given to our compositor on May 10, 1837.

The beauty of this passage is that Carey and we know that Larrit could easily be wrong about Olivier’s phantoms, and may already in part have been wrong; that although all of Olivier’s words turn out to belong to Larrit, we are nevertheless invited to believe in the independent existence of the muted Olivier; and that the conversion of servant and master into a pair of friends is indeed a proof of one of democracy’s most attractive possibilities, and a major theme of this novel so full of intriguing themes. Sainte-Beuve suggested that Tocqueville “got married to America with deep reservations.” Olivier merely wants to marry an American (but can’t bring himself to take her back to France); and as he will finally begin to realize, a rogue Englishman has become his America.

We’ve had some hints of Larrit’s authorship, even if we didn’t know what to make of them. The novel opens in Olivier’s fussy, more than slightly pampered voice (speaking of his mother, he says, “I relished those occasions, by no means infrequent, when she feared that I would die”), which continues for about thirty-five pages recounting events of his childhood and aspects of French history up to the first restoration of Louis XVIII in 1814 (the second took place a year later, after the return and defeat of Napoleon).

We turn the page and a new voice, under the heading “Parrot,” talks to us directly. “You might think, who is this, and I might say, this is God.” He might say he is Peter Carey, but that would be a bit indiscreet; and in any case he is not going to say he is God. He is going to say his nickname is Parrot, and that he is the son of an English journeyman printer, and that he is twenty-four years older than Olivier. He seems a little worried about this and has plainly been reading the previous pages: “To belabor the point, sir, I was and am distinctly senior to that unborn child.” Not a man to think women might be reading him either. Here Carey is interested not so much in the textuality of the text (in his earlier novel True History of the Kelly Gang he lets us know the form and state of preservation of each notebook or set of pages that is supposedly transcribed for each chapter) as in the human and historical location of the storyteller, the spot in time and place where the narrative begins its life. A story told by no one is like the philosophical view from nowhere, and that is part of Larrit’s joke about saying or not saying that he is God.

In this novel Carey provides quiet but consistent reminders that this story is being told by someone, and that we are reading it (or imagining we are listening to it). “So wait a minute. Sit down, find a chair and pour yourself a tot of rum and think what I am telling you.” “Sir, it was not there”—referring to the house in New York that Larrit was looking for. And with his “sir, madam,” Larrit considers at least once that he may have a mixed audience. Even on rereading we tend (rightly) to forget that Larrit is impersonating Olivier, but that only means there is a sudden, delicious pleasure in remembering that the object of a sentence like the following is also its author: “In short, John Larrit was the sort of narrow-eyed and haughty character on whose account one might wisely cross the road.” And there is a greater pleasure still in realigning the following picture, in which Olivier watches a steamboat arrive at Philadelphia:

Advertisement

On the starboard side, as it drifted silently toward the dock, stood what might have been the emblem of America: frock-coated, very tall and straight, with a high stovepipe hat tilted back from his high forehead. I thought this is the worst vision of democracy—illiterate, hard as wood, overdressed, uncultured, with that physiognomy I had earlier observed in the portrait of the awful Andrew Jackson—a face divided proudly in three equal parts: hairline to eyebrows, eyebrows to nose, lips to chin. In other words, the face of one who will never give any weight to the wisdom of his betters…. The specter raised a hand in salute and I realized it was my own servant.

How well Larrit knows Olivier’s mind. But of course Olivier does in time begin to understand the wisdom of not attending to the wisdom of one’s betters—another form of the American joke or secret, perhaps.

Like Tocqueville, Olivier came to America to study the prison system—although unlike Tocqueville he was shipped off by his anxious mother to keep him out of trouble during the July Monarchy. Larrit is the servant she has, through Larrit’s own mildly demonic protector, attached to Olivier, and the relation doesn’t start out well. Olivier thinks of Larrit as “the awful footman,” and Larrit doesn’t like either his job or Olivier, and doesn’t want to go to America. Still, they get along, managing their mutual scorn with skill and only occasional bad lapses.

Olivier is the aristocrat we may think we know and the now aging Larrit is the hero of his own picaresque novel, unfolded for us gradually as the pages progress. His father became associated with a group of printers in England who were forging banknotes, were caught in the act, and most of them, including Larrit Senior, executed. The boy, on the run, is swept up by a French aristocrat and spy who almost incidentally has him transported to the Antipodes. As Tocqueville himself remarks in a moment Carey must have particularly liked, “in our day the English courts of justice are busy peopling Australia.” Larrit marries there and has a child, but is carried away once again by the aristocrat and by the promise of fame in France—Larrit’s real love is engraving and printing. Now he has a mistress, Mathilde, who is a painter, and he is nicely settled in Paris, where even Mathilde’s ancient mother is an appealing part of the picture. Fortunately Mathilde, after an initial fit of rage, is ready to seek her fortune in America.

And so the members of the odd couple (or quartet) begin their American journey. They see a lot, they miss a lot, they quarrel. Olivier begins to understand American finance, and Mathilde, to Larrit’s dismay, more than understands the art of insurance fraud. Olivier himself says that a servant is a “foreign land” to him but he doesn’t yet know that the Anglo-Australian Larrit is at least one sort of model of America. He has some clues, though. America is the place where a Frenchman who started out as a draper’s son can have a magnificent library. Olivier thinks of this fact as “one of those dazzling visions of America, sufficient to make one abandon one’s necessary fears”—there is a nice if slightly desperate touch of loyalty to prejudice in the word “necessary.”

America is full of “drunken wildness” but also contains a witty and beautiful young woman who speaks French and wants to read Molière. This is the woman Olivier falls in love with and seeks to marry. It’s true he has some difficulty distinguishing between the woman and the country—“if I had fallen in love with America generally, then I was both engaged and disturbed by the daring and beauty of Amelia Godefroy,” “was I in love with America or Amelia?”—but he finally sorts things out:

I loved her so.

I did not love her country. It excited and repulsed me, but I would live there. I would die there. I would see only what was good. I would do good. I would make my name in America. I would make myself into America. I would write the first great book describing the great experiment.

He has reached this clarity, however, only because the affair is over. He can’t bring himself to take Amelia back to France to meet his parents and live his French life, and she won’t marry him if he won’t. The promised book is a love song to what didn’t happen.

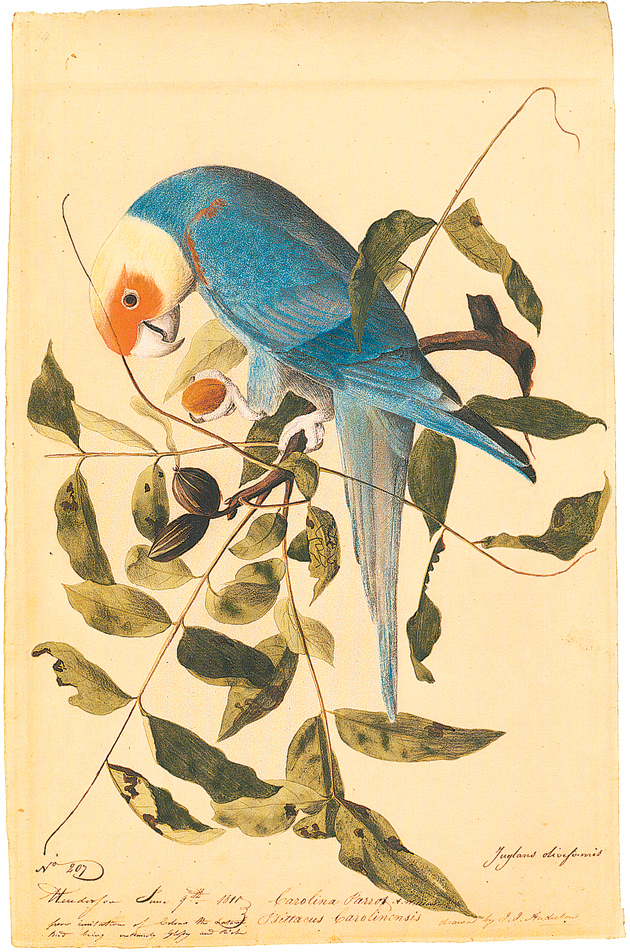

Larrit, meanwhile, has a different desire. For all his wit and energy, he has suffered from his travails and doesn’t really know who or what he is. He feels that he shouldn’t have left Australia, shouldn’t have played the role of the servant for so long, should have tried his hand harder at the art he thought he cared about. The very survival of some of his friends is a rebuke to him. Escaped from the fire at the printer’s in England long ago, an engraver named Watkins is now living in New York and creating a magnificent book with images of all the birds of America, an Audubon before Audubon.

At one point the American Frenchman with the library asks Larrit what he wants, and he responds with the perfect, un-American dream: “To be still.” And then: “Not the road…. Not the sea.” It is part of the generosity of Carey’s thinking that Larrit in the end has his wish, a handsome, quiet house and marriage to Mathilde. This America, if not Tocqueville’s and many of the versions of America we know, has room for un-American hopes, including absence of motion.

It’s true that when Olivier comes to call on the couple he assumes he is still the master and takes the best bedroom as his natural right, leaving Larrit fuming about how to get him out of it. Still, that’s equality of conditions, in Tocqueville’s famous phrase, even if it’s temporarily upside down and looks like the old regime. Olivier has said that “the once detestable Parrot could have no other name than Friend,” Larrit has confessed that he misses his ex-master when he is not there (“I never thought I would think such a thing in all my life”), and even as he’s trying to think of ways of turfing Olivier out of their bed he sees in Mathilde’s eyes the recognition of one kind of democracy in America: “I knew she was moved by this most impossible of friendships, perhaps the only example of its type the world had ever seen.”

The background to all this closing calm and amity, as indeed it is to Tocqueville’s vision of a pacific democracy, is violence and upheaval: the aftermath to the French Revolutions of 1789 and 1830 and the broader fear, represented in Larrit’s endangered and world-crossing life, of an unbreakable cycle of punishment and cruelty. Carey has a particular take on this scene, not an answer or even a question but an image. We hear directly about the French executions of 1793, but young Olivier’s “first lesson in the Terror” concerns not his family’s immediate fear but the slaughter of his grandfather’s pigeons. “The peasants put the birds on trial for stealing seeds,” Olivier is told. “They found them guilty and then they wrung their necks.” A little later, now grown up, Olivier is shocked to see the wisteria on an aristocrat’s dwelling treated as if it were “a living thing, abused, attacked, wounded, hacked, pulled away from the house,” and he makes the connection (and another connection) for us:

I felt sick to see how it had been punished, as the pigeons had been punished, as it was said the printers of rue Saint-Séverin had held a trial and hanged their masters’ cats.

There is a related moment in True History of the Kelly Gang, where the outlaw’s mother tells of a group of men in nineteenth-century Ireland who disemboweled a horse because they couldn’t get at the horse’s master:

She heard grown men blame the horse for taking their common land they said the proof were having Ireland on his head [the horse has a blaze on its forehead that is said to be “exactly in the shape of the map of Ireland”] and they demanded of the poor beast why they should not take Ireland back from him.

Two trials and a lynching. Of birds and cats and a horse. The horror, I take it, stems not only from the innocence of the victims but also from the solemn impersonation of justice and the undiluted devotion to symbolism. It is because these creatures are so different from us that they can be conscripted for these rites, and it is because distorted ideals lie behind the rites that they can seem acceptable—to some. But what about differences among humans, and the symbolisms of rank and class and race? How different is the idea of Europe from the idea of America, and if you weren’t an impossible friend would you have to be a possible or even probable enemy? I don’t know what to make of a fact Carey is far too subtle to mention, namely that one of the historical Tocqueville’s pleasures in the new world was shooting parrots. “We killed a flock of pretty birds,” he writes, “that are unknown in France…. It was thus that I killed red, blue, and yellow birds, not forgetting the most brilliant parrots I’ve ever seen.” At least he spared them the mock trial or mock justification; and readers of Peter Carey know an even more brilliant Parrot.

This Issue

July 15, 2010

What Obama Should Have Said to BP

-

*

Quoted in Leo Damrosch, Tocqueville’s Discovery of America (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010), p. 36.

↩