In a June 21 survey of the public’s response to the health care reform bill passed by Congress in March of this year, the Kaiser Family Foundation found that while 48 percent of those polled were favorable to the bill, 42 percent were confused about it and 41 percent were opposed—a number that has been even higher in other polls.

No wonder. Republicans have sought to make health care reform Barack Obama’s “Waterloo,” as South Carolina Senator Jim DeMint put it in July 2009, by scaring the public. Ominous and utterly false warnings about “death panels,” a government “takeover” of American medicine, and “pulling the plug on grandma” followed. With Republicans hoping to use their opposition to the bill to gain seats in this fall’s midterm elections, there is little sign that such attacks will stop.

The irony is that for all the apocalyptic rhetoric, the new health reform law is anything but radical. In fact, it closely resembles the 2006 reform in Massachusetts supported by then- governor Republican Mitt Romney.1 And most strikingly, it does not replace the current mix of US health insurance schemes with a single public health insurance program like Medicare. Instead, the 2010 reform legislation introduces a complex system of subsidies, mandates, regulations, and programs that build on our present patchwork arrangements and will affect Americans in different ways and at different times, depending on income, age, employment, and other considerations.2

1.

The bill, known as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, begins to take effect this year but many of its provisions will be carried out during the coming decade. As of now, a majority of working-age adults and their children—some 157 million people—obtain private health insurance through their employers, while virtually all Americans over age sixty-five, as well as younger adults with permanent disabilities, are covered by Medicare. Low-income Americans who fit certain demographic categories, such as pregnant women and children, have access to Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). (These two government insurance programs cover nearly one third of all US children.) Still others depend on a loose health care safety net, including community health centers that provide subsidized care, as well as on hospital emergency rooms that must by law see all patients, which of course doesn’t mean they will get timely or adequate care.3

There are sizable gaps in US health insurance coverage. Some 46 million persons—over 16 percent of the population—have no health insurance. Millions of others are underinsured, with policies that do not provide adequate coverage for costly care. A high percentage of workers in small businesses are not covered by their employers and find purchasing their own insurance prohibitively expensive. Those with preexisting conditions like diabetes or asthma face particularly serious obstacles since insurers vary premium rates by health status and regularly deny coverage to those they regard as expensive risks.

Medicare’s benefit package and financial protection is limited. Patients must pay for the first $1,100 of hospitalization costs as a deductible, as well as 20 percent of the costs of physician services, and there is no limit on the total costs they can incur.4 Low-income adults without dependent children are generally not eligible for Medicaid, leaving many of the nation’s poor uninsured. Most of the nation’s seven million uninsured children are eligible for the Children’s Health Insurance Program or Medicaid, but are not enrolled in them. That itself is a testament to the confusion created by our complex insurance arrangements.

The measures of US health—including life expectancy, infant mortality, and deaths preventable by medical care—remain mediocre compared to other rich nations. At the same time, American medical care is notoriously the most expensive in the world. Premiums for family coverage under employer-sponsored insurance now average over $13,000 a year. Expenditures on health care in the United States amount to more than $2.5 trillion, or about 17 percent of national income, while Western European democracies average about 10 percent.

2.

Despite such deep flaws in the US health care system, the central assumption of both the Obama administration and the Democratic leadership in Congress was that only legislation that did not seek to radically change it had a chance of success.5 That political calculation, in turn, was based on the view that the Clinton administration’s health reform effort failed during 1993–1994 because it tried to change too much and provoked too much opposition from insurance companies and other powerful interests.

This time around, reformers hoped to reassure the large number of insured Americans who say they are satisfied with their current coverage that they had nothing to fear from change. Democrats also wanted to work with rather than fight against the health care industry. They hoped to gain support from the insurance, hospital, and pharmaceutical industries, which stood to gain financially from expanded insurance coverage and had the financial resources and political influence to undercut reforms they opposed. As a consequence, the creation of a Canadian-style health program, in which universal insurance—Medicare for all—is provided by the government, was never seriously considered. Such a reform would have caused, in the administration’s view, too much disruption of prevailing arrangements and led to an inflammatory and unwinnable debate over “socialized medicine.”

Advertisement

In building on the existing system, the 2010 reform law largely emulates the 2006 Massachusetts health reform, which expanded coverage by broadening eligibility for Medicaid, grouping the uninsured into a newly created purchasing pool, and providing them, according to their incomes, with subsidies to purchase insurance. Massachusetts residents are required to obtain health insurance or pay a fine. The 2010 law also followed Massachusetts in mostly deferring the harder question of how to reduce the rate of inflation of medical costs in favor of expanding coverage.

During the 2008 presidential campaign and 2009–2010 health reform debate, Democrats added an important proposal to the Massachusetts model. They suggested that uninsured Americans should have access to a newly created public insurance plan modeled on Medicare. It was designed to be a means to control health care spending by using the substantial purchasing power and lower administrative costs of the US government. This proposal was opposed by conservative Democrats, Republicans, and the insurance industry. Although a weakened public plan passed in the House, Democratic leaders could not get it included in the final bill.

3.

How will the new law work? First, all Americans who earn less than 133 percent of the federal poverty level—in 2009 it was $10,830 for an individual—will become eligible for Medicaid. For the first time, Medicaid will offer coverage solely on the basis of income and regardless of family circumstance—including the single adults without children who are now excluded.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that, as a result, about 16 million Americans will gain insurance coverage through Medicaid. The federal government would initially pay all of the costs for this expansion, which begins in 2014; after 2020 Washington would finance 90 percent of the costs, with states funding the remainder. In contrast to the attention given to the failure of the public option to pass Congress, this major change in government coverage for the poor has been given little notice.

As for Medicare, the law actually improves its benefits. The infamous “donut hole” in Medicare’s prescription drug coverage—beneficiaries have to pay all medication costs after exceeding a predetermined threshold and before reaching a second, much higher threshold—will be phased out by 2020. Medicare beneficiaries will also have better preventive care, including payment for an annual wellness visit.6 Some primary care physicians treating Medicare patients will be paid more—a bonus of 10 percent in areas short of doctors—and those treating Medicaid patients will also be paid at a higher rate.7 On the other hand, persons enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans—offered by private insurers that contract with the federal government—could lose extra benefits beyond what the standard Medicare program offers. These private plans have long been overpaid by the government relative to what it costs them to take care of Medicare patients.

Most Americans under age sixty-five will continue to receive employer-sponsored coverage. As a new feature, children can stay on their parents’ insurance plans until age twenty-six. New regulations banning insurers from imposing caps on both annual and lifetime payments will also benefit policyholders. Larger employers will have to offer health coverage to their workers or pay a penalty ($2,000 per worker) to the federal government.8 Smaller employers with fewer than fifty workers will be exempt from this requirement, and, depending on their average wage, businesses with twenty-five or fewer workers are eligible for tax credits to help them buy health insurance for their workers.

The law also expands coverage by offering subsidies to uninsured Americans to purchase insurance in newly formed health benefit exchanges. Each state is expected to set up and administer these exchanges as a regulated market for health insurance. If a state chooses not to do so, its residents can join a federally sponsored exchange. In either case, people will choose from a variety of private insurance plans within each exchange, with federal subsidies available on a sliding scale to help them pay their premiums. Those with incomes up to 400 percent of the federal poverty level (i.e., now up to about $43,000) will be eligible for subsidies.

In all, 29 million Americans are expected to obtain insurance through the exchanges by 2019. This pooling of the uninsured, the reform assumes, will increase the purchasing power of the group, reduce administrative costs, and thereby produce lower-priced plans than would otherwise be available to persons without employer-based coverage.

The insurance exchanges will be regulated extensively. Starting in 2014, insurers will not be able to deny coverage to would-be policyholders or charge them higher premiums because of their health status (though insurers can vary premiums by age). Insurers will also be prohibited from retroactively canceling coverage for sick policyholders. Most Americans will be required to obtain health insurance or pay a federal tax penalty—starting in 2014 at $95 per person or 1 percent of taxable income, whichever is greater, and then increasing to $695 or 2.5 percent of taxable income by 2016.

Advertisement

4.

The CBO estimates that 32 million Americans will gain coverage through the expansion of Medicaid, subsidies, and insurance exchanges. This will make an enormous difference to the financial circumstances of many Americans with modest means and large medical expenses. Contrary to what conservative critics have claimed, the reform will undoubtedly mean less, not more, rationing of medical care as tens of millions of uninsured persons gain access to health insurance.

By broadening health insurance coverage, the law moves the United States closer to the principle that no one should go without access to medical care. In regulating the health insurance industry, with provisions to end discrimination on the basis of preexisting conditions, it brings about a long-overdue expansion of federal authority. In these ways and more, the Affordable Care Act is a substantial achievement.

At the same time, large gaps remain between the problems of American medicine and the remedies that Congress has adopted.9 Even if the Affordable Care Act were fully implemented, an estimated 23 million people would still lack insurance in 2019. We cannot know precisely who will be without coverage a decade from now. But analysts expect that the uninsured will be made up of three groups: undocumented immigrants who are ineligible for federal subsidies or Medicaid; Americans who still find coverage, even with subsidies, too expensive to purchase on their own but aren’t poor enough to qualify for Medicaid; and healthy people who can afford to buy coverage but will instead choose the cheaper option of paying the penalty for not having insurance. In any case, the United States, alone among industrialized democracies, will likely continue to have a large uninsured population for years to come.

Nor does the legislation provide Americans with adequate safeguards against rising medical costs. Many Americans with health insurance will still face substantial and growing medical bills. Compared to the health insurance programs of other industrialized democratic nations, the law has large gaps in coverage and limited benefits.

In fact, the expansion of insurance coverage and regulation described in the law is hardly straightforward. New insurance plans will be regulated differently than existing policies. Health plans that were in place by March 23, 2010, and do not, for example, significantly reduce their current benefits—“grandfathered plans”—will be exempt from some new rules, such as a requirement to cover preventive services without obliging patients to share the costs. A new federal high-risk pool for people who can’t find affordable coverage because of their health status will temporarily coexist with state high-risk pools, with each pool having varying premiums and eligibility criteria. And as an early controversy over requirements to cover children with preexisting conditions showed, insurers whose profits are at stake can be expected to seek loopholes to evade the new regulations. According to the law, the secretary of health and human services must write the thousands of pages of regulations necessary to implement it, and these will be subject to congressional scrutiny and intense lobbying by the health care industry.

In addition, the government will have to increase its efforts to make eligible people aware of the expansion of Medicaid and of the availability of health insurance subsidies. It is far from clear how successful states will be in establishing and operating health insurance exchanges for the uninsured (or even how many states will do this on their own). One consequence, then, of building on the existing system is that the new law will require coordination of a great many disparate policies if coverage goals are to be met and if the health insurance marketplace is to be transformed.

Perhaps the largest shortcoming of the reform, though, is the absence of reliable, system-wide controls on medical costs. The law takes steps to slow down the rate of increase in Medicare spending, such as cutting projected payments to hospitals and private insurance plans that contract with Medicare (private insurers will also face new limits on the amount of overhead costs they can take out of premiums). In addition, an Independent Payment Advisory Board will be established, with authority to recommend reforms designed to slow Medicare spending that Congress must consider under special legislative rules.10 The law aims to save over $400 billion in projected Medicare spending during the next decade. But even medical care industries—such as hospitals—that agree to those savings may resist these measures as their effect on revenues grows in coming years, though Medicare’s record in sticking with adopted policies that contain costs is generally strong.11

Outside of Medicare, the measures to slow health care spending are far less impressive.12 Many health policy analysts believe that the law contains a serious instrument to restrain spending, namely the so-called “Cadillac tax” on expensive insurance plans. By taxing high-cost private insurance plans, insurers and employers will trim overly “generous” benefits and Americans will—so it is hoped—use fewer medical services of low value. Yet this controversial policy is not slated to begin until 2018 and there is no guarantee that a future Congress and president will implement it then.

Taxing health care benefits—even if restricted to the most generous plans—is hardly popular and is fiercely resisted by labor unions. Furthermore, even if the Cadillac tax does go into effect and saves significant money, it could end up reducing benefits and raising costs for people who do not have comprehensive coverage. After all, the variation in the price of insurance policies reflects differences in age and health status, not simply the scope of benefits. In other words, this feature of the health reform could increase the portion of the population who are underinsured.

The law’s strategy to contain costs additionally rests on a series of reforms aimed at improving medical care delivery and health outcomes: paying hospitals on the basis of quality; bundling payments together for inpatient and outpatient care; funding research that compares the clinical effectiveness of medical treatment options; and providing greater coverage of preventive services. It also encourages the formation of so-called accountable care organizations that create networks of primary care doctors, specialists, and hospitals to care (and receive payments) for a defined set of patients. Many of these reforms will be implemented initially in Medicare—a newly established Medicare innovations center is charged with testing payment reform—with the hope that successful policies will then spread through the private sector.

Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius says that “every cost-cutting idea that every health economist has brought to the table is in this bill.” That is probably true—but it also shows that American health policy researchers pay scant attention to international experience.13 No other country relies primarily on the use of electronic medical records or paying medical providers on the basis of relative “quality” in order to control spending. The new law seems based on the hope that if a large variety of reforms are tested, at least some will succeed; but nobody knows how many will work in practice or whether they will save money at all.

We do know that other rich democracies that spend much less than the US on medical care do so largely by adopting budgetary targets for health expenditures and by tightly regulating what the governments and insurers pay hospitals, doctors, and other medical care providers. Outside of Medicare, the current reform contains no such measures.

The Obama administration, confronting enormous opposition over proposals to expand coverage, chose mostly to defer addressing the political problems of cost control. But the experience of Massachusetts shows that the issue cannot be avoided for long. Since passing its 2006 law, the state has found that costs continue to rise. The expansion of coverage and the requirement that individuals purchase insurance, alongside rising premium costs, have generated political controversy in Massachusetts, and the same is likely to happen as the similarly designed national health reform is carried out. As a result of the new law, pressure will increase on the federal government to moderate the growth in health care costs—especially in view of sizable budget deficits. Yet while Massachusetts officials are discussing cost control options, they have not adopted any serious spending limits to date, a reminder of how difficult the next stage of health reform remains.

5.

Republicans are mounting a campaign to “reform and repeal” the law. Twenty-one states—twenty of which have Republican attorneys general—are suing the federal government to overturn the law. They contend that the provision requiring Americans to purchase insurance or pay a tax penalty is unconstitutional. As Simon Lazarus and Alan Morrison persuasively argue, and many legal scholars will agree, there are ample precedents for the federal powers required and the lawsuits are best viewed as part of an ongoing Republican “general campaign to discredit health care reform.”14 Still, the Supreme Court will ultimately determine the constitutionality of the individual mandate to buy insurance and we can’t be sure how the Court will rule.

The political challenge to health reform is more serious. Not only does the law lack support from a majority of Americans—as the Kaiser survey showed—but the upcoming midterm elections are likely to produce a Congress more hostile to it. For the moment, any repeal legislation passed by a Republican Congress would be vetoed by Obama, and Republicans are almost certain not to have the two-thirds majority necessary to override a presidential veto. But if a Republican wins the presidency in 2012 and takes office with Republican majorities in Congress, then reform could be in serious difficulty.

That is one reason why Democrats frontloaded the law with some popular, low-cost programs. In 2010 alone, provisions that will go into effect include a prescription drug rebate for Medicare beneficiaries; health insurance tax credits for small businesses; the prohibition on insurance companies denying coverage to children with preexisting conditions; and the requirement that insurers allow parents to keep children on their plans until age twenty-six. It will be very difficult for Republicans to overturn these and other policies regulating health insurers that are likely to attract public support.

But the major insurance provisions in the health reform law—including expanded Medicaid and federal subsidies to help the uninsured purchase insurance—are not set to begin until 2014. Democrats devised this delay in large part to fit the ten-year cost of the bill within a self-imposed $1 trillion dollar limit on new federal spending for health reform. Those fiscal gymnastics helped Democrats both to obtain a good CBO score for the reform and to hold onto the congressional majority for health care legislation.

The delayed implementation also produced a major risk. If Obama does not win reelection, a Republican administration and Congress could overturn or replace the core policies designed to expand coverage; they might well target the less popular measures such as the individual and employer mandates or even the cuts in Medicare spending growth that are crucial to financing the expansion of insurance coverage.

6.

In the short term, if the reformers are to win a defensive struggle against repeal, they will need to clarify the benefits of reform for the public, no easy task given the extraordinary amount of misinformation that has been spread over the past two years.15 The bill has provisions—such as insurance regulation and the expansion of Medicare benefits—that have been popular in some polls. But public awareness of many of those features is limited. While pro–health reform advocacy organizations such as Health Care for America Now spent considerable resources during the 2009–2010 debate, it is unclear that they will be able to exert similar influence over how the reform is carried out in coming years. The heavily financed insurance companies and other groups representing the health care industry will face no such constraint.

Over the longer term, progressives can try to tighten regulation of premium increases by private insurers, impose stronger controls on spending for medical care, and increase insurance subsidies for lower- and middle-income Americans. They may even press states to introduce their own public plans to compete with private insurers in the insurance exchanges. Because costs are sure to rise in coming years, insurance companies will likely remain a political target. Meanwhile, the immediate challenge facing Democrats is how health care reform will play into the elections—two congressional and one presidential—that will take place between now and the time when the law’s major coverage provisions are scheduled to take force in 2014. As a result, there is enormous uncertainty about how well and how long the patchwork of health reforms adopted in 2010 will hold together.

—July 21, 2010

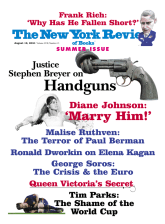

This Issue

August 19, 2010

The Crisis & the Euro

-

1

Romney supported the approach to expanding health insurance coverage in Massachusetts though he opposed and ultimately vetoed provisions in the law requiring employers to pay for their workers’ insurance or pay a penalty. The Massachusetts legislature overturned his veto.

↩ -

2

See the Kaiser Family Foundation, “Summary of New Health Reform Law,” March 26, 2010.

↩ -

3

Uninsured adults are “25 percent more likely to die prematurely than insured adults overall, and with serious conditions such as heart disease, diabetes or cancer, their risk of premature death can be 40 to 50 percent higher.” Statement of John Z. Ayanian, Presented to the Committee on Ways and Means, United States House of Representatives, March 11, 2009.

↩ -

4

Medicare patients currently pay $1,100 as a deductible for each benefit period. A benefit period begins the day a patient starts their hospital stay and ends when they haven’t received inpatient hospital services for sixty days. Consequently, Medicare beneficiaries can have multiple benefit periods in a given year and if so, they would have to pay the required deductible for each new benefit period. See Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Medicare & You: 2010. [www.medicare.gov/publications/pubs/pdf/10050.pdf](http://www.medicare.gov/publications/pubs/pdf/10050.pdf).

↩ -

5

See Theodore Marmor and Jonathan Oberlander, [“Health Reform: The Fateful Moment,”](/articles/archives/2009/aug/13/health-reform-the-fateful-moment/) The New York Review, August 13, 2009.

↩ -

6

Beginning in 2011, Medicare will offer coverage, with no patient cost-sharing, for preventive services recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force.

↩ -

7

Under the new law, primary care doctors seeing Medicare patients in defined health professional shortage areas will receive a 10 percent bonus for their Medicare patients from 2011–2015. Primary care doctors seeing Medicaid patients will have their fees raised to 100 percent of Medicare levels during 2013–2014 (currently, Medicaid payment rates for physicians average 72 percent of Medicare rates). See Kaiser Family Foundation, “Summary of New Health Reform Law,” and Stephen Zuckerman et al., “Trends in Medicaid Physician Fees, 2003–2008,” Health Affairs, April 28, 2009.

↩ -

8

Employers with over fifty workers who do not offer coverage and have employees who received premium credits in the insurance exchange will pay $2,000 per full-time employee, excluding their first thirty employees. Employers with over fifty workers who do offer coverage but have employees who qualify for premium subsidies in the exchange will pay “the lesser of $3,000 for each employee receiving a premium credit or $2,000 for each full-time employee, excluding the first thirty employees from the assessment.” See Kaiser Family Foundation, “Summary of New Health Reform Law.”

↩ -

9

See Jonathan Oberlander, “Long Time Coming: Why Health Reform Finally Passed,” Health Affairs, June 2010, Vol. 29, pp. 1112–1116.

↩ -

10

The board also will make recommendations on how to slow national health expenditures. For more on the IPAB and the rules that Congress must consider its Medicare proposals under, see Timothy S. Jost, “The Independent Payment Advisory Board,” New England Journal of Medicine, May 26, 2010. [content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/NEJMp1005402v1](http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/NEJMp1005402v1)

↩ -

11

On Medicare’s record in sustaining cost saving reforms, see the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities report by James R. Horney and Paul N. Van de Water, “House-Passed and Senate Health Bills Reduce Deficit, Slow Health Care Costs, and Include Realistic Medicare Savings,” December 4, 2009. [www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3021](http://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3021)

↩ -

12

See Richard Foster, “Estimated Financial Effects of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, As Amended,” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, April 22, 2010. Foster, the federal government’s chief actuary for Medicare, estimates that over the next ten years, national health expenditures will increase by $311 billion over current projections as a result of the new law’s coverage expansion and limited cost controls.

↩ -

13

In the days leading up to the enactment of health reform, a “who’s who” of American health economists released a letter touting the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act’s cost containment provisions, including making “greater use of comparative effective research” and “move[ing] Medicare to value-based payment.” See [www.americanprogressaction.org/pressroom/2010/03/av/hcletter.pdf](http://www.americanprogressaction.org/pressroom/2010/03/av/hcletter.pdf).

↩ -

14

See Simon Lazarus and Alan Morrison, “Lawsuit Abuse, GOP Style,” Slate, May 5, 2010.

↩ -

15

The Obama administration, Democrats, and pro-reform groups clearly recognize this challenge and are now organizing a campaign to sell the health care law, which underscores the shortcomings of efforts to build public support for health reform during the 2009–2010 debate. See Sheryl Gay Stolberg, “White House and Allies Set to Build Up Health Law,” The New York Times, June 6, 2010.

↩