Code word “Cromwell”—the warning that German invasion was imminent—was communicated to British army units on September 5, 1940. The 130th Infantry Brigade of the 43rd (Wessex) Division, in which I was serving, was rushed to the southeast coast to take up positions in and around Dover, the British port nearest to occupied France. Our division was said, after the losses at Dunkirk, to be the only fully equipped division in England, but most of us had no experience of war, and in training we had fired only our World War I rifles; there was no ammunition for practice with mortars or antitank weapons. A likely beach for a German landing, St. Margaret’s Bay, a crescent of sand to the east of Dover, was defended by some two hundred Dorset soldiers of my old battalion. (I had just become the brigade intelligence officer because I was fluent in French and German.) I visited them often and found them enthusiastic and full of confidence. “Jerry going to get a nasty shock if he tries to land here,” they said.

At the end of the war I read the German invasion plan, Operation Seelöwe (Sea Lion). St. Margaret’s Bay was one of the main landing beaches all right—heavy air and sea bombardment, parachute troops behind the beach, amphibious and armored units from the sea, followed by infantry divisions would descend on our two hundred faithful defenders with their ancient rifles. Even in 1940 we might have foreseen at least some of this nightmare for ourselves and quailed at the grotesque imbalance of forces, but fortunately Winston Churchill had captured our imaginations. That growling, indomitable voice on the radio had told us that this was our finest hour. In the absence of adequate numbers, armament, experience, or training, his words were our best, perhaps our only, defense. Luckily we did not, in the end, have to put it to the test of resisting a German invasion. Although it was impossible at that time to imagine how we might win the war, it was inconceivable to us that we should lose it. That too was part of the Churchill effect.

1.

Of Winston Churchill at this time Max Hastings writes:

His supreme achievement in 1940 was to mobilise Britain’s warriors, to shame into silence its doubters, and to stir the passions of the nation, so that for a season the British people faced the world united and exalted. The “Dunkirk spirit” was not spontaneous. It was created by the rhetoric and bearing of one man, displaying powers that will define political leadership for the rest of time.

Hastings’s Winston’s War: Churchill, 1940–1945 is a magnificent achievement. After the vast number of works on Churchill that have appeared in the last sixty-five years, one could be forgiven for thinking that everything significant must already have been said, but Winston’s War is something fresh and different. Churchill’s inspired leadership and the unique strength of his will saved Britain from defeat and occupation and did much to make the ultimately victorious alliance possible. Hastings’s wealth of research, quotation, anecdote, and comment builds up a living picture of the genius, as well as of the heroic flaws, of this immensely gifted and fascinating human being.

Hastings’s other books on World War II are remarkable for their stimulating interplay of military strategy, tactics, battles, personalities, and cogent analysis, lit up by firsthand descriptions from soldiers and from the civilians in their path. Winston’s War is one of those rare books that create in the reader a palpable feeling of the excitement, fear, frustration, grief, dread, all-too-occasional elation, and numbing fatigue of those critical days, as well as a lucid understanding of what happened and why. Churchill’s own oratorical, literary, and conversational style and wit provide a vivid, and sometimes hilarious, counterpoint to Hastings’s own succinct and shrewd judgments.

2.

Few leaders can have assumed power in such dire circumstances. Churchill entered 10 Downing Street on May 10, 1940, the first day of the German blitzkrieg on Western Europe. A peace movement, led by the foreign secretary, Lord Halifax, was gaining strength. (Even seventy years later, the thought of making “peace” with a victorious Hitler from a hopelessly weak position, and its inevitable consequences, is terrifying.) Churchill’s first great achievement was to snuff out this catastrophic idea, an effort complicated by the fact that he could not realistically hold out any prospect of an early British military recovery. Only a month later it seemed likely that the whole British Expeditionary Force in France would be taken prisoner. At least the “miracle of Dunkirk” avoided that disaster—when 300,000 troops were rescued and brought back across the Channel, many of them in small private boats—but then France surrendered, and Britain was left to fight Hitler alone.

Advertisement

Churchill’s political position was initially weak. His own Conservative Party for the most part disliked and distrusted him as a maverick and aisle-crosser. In the country at large he was regarded as a mercurial aristocrat and adventurer who was particularly remembered as the begetter of one of World War I’s most spectacular disasters, the Dardanelles operation.

Churchill’s claim to wartime leadership, in Hastings’s words, rested “upon his personal character and his record as a foe of appeasement. He was a warrior to the roots of his soul….” Among British politicians there was no one else with such qualities, but if he was to get the nation behind him to continue the military struggle, he had to gain the confidence of the British people, while at the same time dealing with the greatest threat that Britain had faced in all her history. He won the people’s confidence during the critical summer of 1940 by a display of courage, defiance, and leadership that has never been surpassed.

Churchill’s triumph was that Britain, for more than one year, outlasted the threat of invasion and remained in the fight against Hitler, thus providing a rallying point and base for later allies in the much larger conflict to come. For all the vast risks involved, this was the simplest and most satisfying period of Churchill’s leadership. He alone was in charge.

In June 1941, the Soviet Union, Hitler’s erstwhile accomplice, was invaded in its turn and became an ally in the anti-Nazi struggle. Five and a half months later Pearl Harbor pushed the Americans into war with Japan, and a few days later Hitler, inexplicably, declared war on the United States. On his reaction to the United States’ entry into the war Churchill wrote, “I went to sleep and slept the sleep of the saved and thankful. One hopes that eternal sleep will be like that.”

By December 1941 there were, at last, substantial reasons to believe that the war could, and would, be won, although years of bitter struggle still lay ahead. Ironically, this was also the beginning of the end of Churchill’s predominance as a war leader. The vast resources of the United States and the sheer manpower and size of the Soviet Union would, from then on, steadily reduce the role and influence of Britain and its extraordinary prime minister. Churchill’s already legendary standing in the world certainly mitigated this process, but his influence at summit meetings declined from the triumphal first wartime visit to Washington in December 1941 to the frustrations of Tehran and Yalta (which Churchill called “the Riviera of Hades”)1 and the final humiliation in 1945, when he was voted out of office in the middle of the post–European–war summit at Potsdam.

3.

Although in public Churchill maintained a consistently positive and enthusiastic attitude about his two gigantic allies, his relations with them became a constant and unequal struggle. His late-nineteenth-century, imperial outlook—he had wanted to keep Gandhi in jail during the 1930s—and his sometimes wrongheaded ideas of strategy and operations annoyed FDR, and increasingly irritated the most important American soldier, General George Marshall. Churchill was bitterly aware of Britain’s military failures, the limitations of his generals, and their diminishing role in actually fighting the enemy.

Hastings’s analysis of Anglo-American relations and the relationship between Churchill and FDR is a major theme throughout his book. Britain desperately needed assistance from the United States, but in 1940 the United States was by no means wholly sympathetic to British war requirements, and a large majority of the people and in Congress was determined to stay out of another European war. This greatly limited what President Roosevelt could do to help.

Of the disastrous year 1941, Hastings writes:

American assistance fell far short of British hopes, and Churchill not infrequently vented his bitterness at the ruthlessness of the financial terms extracted by Washington for supplies. “As far as I can make out,” he wrote to Chancellor [of the Exchequer] Kingsley Wood, “we are not only to be skinned, but flayed to the bone.”

Supply purchases were strictly on a cash basis until the end of 1941. To meet these bills, British businesses in the US were sold off at fire-sale prices, and a US cruiser collected Britain’s last £50 million in gold bullion from Cape Town. About the first round of Lend-Lease, Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden wrote, “Our desperate straits alone could justify its terms.”

Personal relations between Americans and British in Washington started, and badly, at the top with Lord Halifax, who had been sent as ambassador to get him out of London after the failure of the movement to negotiate with Hitler. Halifax, who had told Stanley Baldwin, “I have never liked Americans, except odd ones,” hated being in Washington and reported that trying to pin down US officials was “like a disorderly day’s rabbit-shooting.”

Advertisement

At the top level of the US army there were many who had no enthusiasm for another European expedition to fight for the British cause, and some who were openly anti-British. Suspicions of imperial motives also reduced what enthusiasm there was for assisting Britain. There were notable exceptions—Harry Hopkins, Averell Harriman, John Winant, and Edward R. Murrow, for instance—who were indefatigable throughout the war in preserving cooperation and mutual respect between the two countries.2

The personal relationship of Roosevelt and Churchill was, for official purposes at least, an important symbol of warmth and solidarity. Both men were accomplished actors, but at the personal level there seems to have been little real friendship or mutual sympathy. FDR, Hastings writes, had “a capacity for forging a semblance of intimacy,” but the two were very different in character. “Churchill was what he seemed,” Hastings comments. “Roosevelt was not.”

Their first wartime meeting was on a battleship at Placentia Bay, Newfoundland, in August 1941. “It would be an exaggeration to say that Roosevelt and Churchill became chums at this conference or at any subsequent time,” Robert Sherwood wrote. “They established an easy intimacy, a joking informality and a moratorium on pomposity and cant—and also a degree of frankness in intercourse which, if not complete, was remarkably close to it.” At the time, both men believed that the Soviet Union would collapse before the Nazi onslaught. Apart from producing the Atlantic Charter, a document that was never signed, the talks were desultory. To Churchill’s disappointment FDR never mentioned the possibility of US belligerence.

At their next meeting, in Washington four months later, the US was at war with both Japan and Germany. Churchill stayed in the White House for nearly three weeks (too long for FDR) and addressed, with huge success, a joint session of Congress. It was agreed, at Churchill’s urging, that the war against Germany would be the top military priority. Although Hastings does not mention it, the two leaders also presided at a ceremony at the White House on New Year’s Day 1942, at which representatives of the twenty-six nations, including China and the Soviet Union, then at war with Germany, Italy, or Japan, signed a Declaration of United Nations (the first time that phrase was used) that committed the signatories not to make a separate peace and to support the principles of the Atlantic Charter.3

This may well have been the apogee of the famous relationship. Although he never failed in public to put a good face on it and made a consistent effort to maintain the best possible relations with Roosevelt, for Churchill the growing ascendancy of the US and the Soviet Union as leaders of the alliance must often have been irksome and even painful.

Churchill’s ideas about war differed fundamentally from the strategic principles that guided George Marshall and his fellow generals. Hastings explains that while the basic American doctrine was the concentration of forces, Churchill tended to favor more romantic forms of warfare that scattered Allied forces to exotic and unexpected places. Churchill disliked the huge gamble of the invasion of Europe across the Channel and repeatedly urged operations in the Mediterranean as the alternative starting point for the second front. The disastrous Italian campaign was a part of this preference, as were such ideas as landing an invasion force on the Istrian peninsula in the northern Adriatic to advance into Austria and the Balkans, the capture of Sumatra as the base for an Allied landing in the Bay of Bengal, and various smaller operations like the futile and expensive raids to secure Rhodes and the Dodecanese Islands and distract German forces from the Russian front. Churchill’s enthusiasm for “setting Europe ablaze” by sending arms and representatives to resistance movements also proved unrealistic, except as a postwar source of national self-respect. Only in Yugoslavia and in Russia did resistance movements significantly influence German deployment.

Churchill’s insistence on sending a British force to Greece in 1941 to fight the German invaders did nothing for the Greeks and, as Hastings points out, weakened the British forces in North Africa at the moment when Erwin Rommel and his Afrika Korps were about to arrive in the desert. The prime minister’s later ideas for splitting up the Allied forces to fight on different fronts not only maddened American planners but sorely tried the already severely strained patience of the Chief of the Imperial General Staff and Churchill’s military keeper, General Alan Brooke.

Churchill’s relationship with his generals was often unhappy. He was furious when perhaps the ablest of them, Archibald Wavell, the commander in the Middle East, refused his directive to send a large part of his already undermanned army back to England in 1940. Churchill formed a false and insulting (“wavering Wavell”) opinion of the general, which Anthony Eden and others tried unsuccessfully to dispel. In his recent book, Warlord, Carlo d’Este describes Churchill’s hostile and overbearing treatment of Wavell when he summoned him to London.4 General Claude Auchinleck, whom Churchill put in Wavell’s place, was also removed after Churchill found him inadequate. Bernard Montgomery, who succeeded Auchinleck and achieved Britain’s first World War II victory at El Alamein, irritated Churchill by his cockiness and arrogance. Churchill’s favorite, General Harold Alexander, whom he made commander in chief in the Mediterranean, was generally considered a mediocre and indecisive commander. All in all, both the British army and its generals were a disappointment to Churchill.

Contrary to what some claimed at the time, Stalin never shared Churchill’s and FDR’s view of the war as a common struggle for freedom and decency against the forces of evil and tyranny. His two priorities in relations with his new allies were to get weapons, tanks, aircraft, and other military supplies for the Red Army, and to persuade the Americans and British to launch a second front in Europe as soon as possible to draw off German army units from the Russian front. On most other matters the Russians were rude, peremptory, uncooperative, suspicious, and supremely ungrateful for the large amounts of aid that both the US and Britain, initially at a terrible cost in lives and ships, delivered to them for the rest of the war.5

A nineteenth-century aristocratic imperialist who had championed the counterrevolutionary army in Russia after the 1917 revolution, Churchill was an unlikely friend for Stalin, even supposing that the concept of friendship existed in the Kremlin. Both FDR and Churchill referred to Stalin as “Uncle Joe,” but for Churchill in particular this friendly appellation became increasingly hollow as the war went on. As the Soviet army, taking huge casualties, steadily destroyed Hitler’s divisions, Churchill maintained in public his official admiration for a heroic ally. The British public, and especially the workers, were enthusiastic about the Soviet war effort and organized demonstrations for an early second front. They tended to like the Russians, of whom they had no direct experience, better than the Americans whom they considered rich, patronizing latecomers—thus the regrettable saying, “overpaid, oversexed, and over here.”

In his dealings with FDR and Churchill, Stalin had one unique advantage. There were Communist sympathizers at the highest levels of government in London (John Cairncross in the War Cabinet and later at the Bletchley Park code-cracking center, Anthony Blunt in MI5, Guy Burgess and Kim Philby in the Secret Intelligence Service, and Donald Maclean in the Foreign Office) and in Washington (Harry Dexter White at the Treasury, Nathan Silvermaster at the Board of Economic Warfare, and Alger Hiss at the State Department). These comrades and others sent vast quantities of papers and information, not to mention decrypted Axis messages, to Moscow through their Soviet controllers. As a result, Hastings writes:

Before every Allied summit the Russians were vastly better informed about Anglo-American military intentions than vice versa. So much material reached Stalin from London that he rejected some of it as disinformation, plants by cunning agents of Churchill.

This material included minutes of Anglo-American arguments over many questions, including the timing and location of the second front. Stalin could thus often play FDR off against Churchill on sensitive matters.

4.

Before 1940, the phrase “great man” was seldom if ever used about Churchill. After 1940 even those who disliked him did not fail to use it. It was as if all his great gifts had fallen into place in that year and revealed someone genuinely extraordinary. Of his physical courage there had been no doubt since he had ridden as a Hussar in the British army’s last cavalry charge in the battle against the Mahdi’s dervishes at Omdurman in Sudan in 1899. He seems to have felt genuinely at home on the battlefield, and as prime minister he longed for “the music of gunfire,” as Hastings calls it. Air raids on London often found him with his binoculars on the roof of the building in Whitehall that housed his far-from-secure dungeon headquarters, a crowded, improvised, busy place, where the War Cabinet spent most of its working hours.6 He liked to visit Dover, the only place in England under direct German long-range artillery fire. It took King George VI’s authority to stop him from observing the D-Day landing from a cruiser off the invasion beaches. (“A man who has to play an effective part, with the highest responsibility, in taking grave and terrible decisions of war may need the refreshment of adventure,” Churchill wrote aggrievedly of this episode.) He finally got to Normandy on D plus 6, and came home to find the first V-1s dropping on London. Churchill never hesitated to take long and hazardous journeys, usually in the icy and noisy discomfort of a Liberator bomber.

Churchill’s strength of mind and will and his capacity for virtually endless work made him the most powerful and authoritative prime minister in British history, a position tempered by his reverence for the monarchy and the House of Commons. Even in 1942–1943, when he was subjected to severe and in some cases plausible criticism both in Parliament and in the country at large—over the conduct of the war and because he insisted on being minister of defense as well as prime minister—his ability to rally the House and the country to his side remained unchallenged.

His speeches often contain passages of lasting beauty, like the one that Hastings has chosen as an epigraph for his book. It comes from Churchill’s eulogy in the House of Commons for his predecessor Neville Chamberlain, a man whom he had despised until his last courageous struggle with cancer.

History with its flickering lamp stumbles along the trail of the past, trying to reconstruct its scenes, to revive its echoes, and kindle with pale gleams the passion of former days.

Churchill’s 1940 speeches are famous, but many others should last as monuments to the charm and variety of parliamentary oratory. In late 1944 Churchill was being fiercely attacked in Britain, the United States, and the Commons for his supposedly reactionary policy in Greece. Admiration for the Soviet Union seemed, Hastings explains, to have blinded his attackers to the probability that if Britain did nothing, the Communists would seize Greece as ruthlessly as they were taking over Eastern Europe and the Balkans. On Christmas Eve 1944, over the tearful protests of his long-suffering and admirable wife, Clementine, Churchill left for Athens with Eden to try to extinguish a brutal civil war between the Communist resistance movement, ELAS, and the provisional government. After Churchill’s visit, 90,000 British troops were stationed in Greece to secure the country.

On his triumphal return to London, Churchill addressed the Commons:

The House must not suppose that, in these foreign lands, matters are settled as they would be here in England…. If I had driven the Deputy Prime Minister out to die in the snow, if the Minister of Labour had kept the Foreign Secretary in exile for a great many years, if the Chancellor of the Exchequer had shot at, and wounded, the Secretary of State for War…if we, who sit here together, had back-bitten and double-crossed each other while pretending to work together…and had all set ideologies, slogans or labels in front of comprehension, comradeship and duty, we should certainly, to put it at the mildest, have come to a General Election much sooner than is now likely.

5.

Churchill remained focused on winning the war to the exclusion of all other concerns, and as the European war drew to its close, this became a severe problem. As Hastings puts it, “His flagging health, rambling monologues and refusal to address business that did not stimulate his interest posed great difficulties.” He had no interest whatever in postwar reconstruction, and public awareness of this fact was certainly one of the elements that told against him in the 1945 election. Britain was still a class-ridden country, and even during the war there had been serious strikes and work stoppages. The working people and the soldiers who had hailed “Winnie” in 1940 concluded in 1945 that he did not understand their concerns for the future or the enormous changes, both external and internal, that nearly six years of war had brought to England.

Winston Churchill has remained a uniquely interesting personality. He lived to the full a long and adventurous life during which he supported himself by writing a prodigious number of books. He was a better than average amateur painter. He was a good soldier, a great orator, and a dedicated parliamentarian. His wit and brilliant repartee survive in hundreds of anecdotes and memoirs. He was a bon vivant whose consumption of wines and spirits was legendary.7 He was a devoted family man, although he also observed of his only son, “I love Randolph, but I don’t like him.”

Churchill had a grand vision of the sweep of history and his own place in it. Even in his last term as prime minister in the 1950s, when his powers were sadly diminished, he felt it his duty to try to stem the potentially suicidal drift toward a full-scale nuclear arms race. In 1952 he proposed to Eisenhower, who had just become president of the United States, that they go together to Moscow to persuade Stalin that the potential for nuclear disaster overrode in ultimate importance all other considerations and differences. Washington was not interested in this approach.

During the war Churchill lived especially by two precepts: In Defeat Defiance and In Victory Magnanimity. (The British violated the second when they allowed Cossacks and other anti-Communist prisoners to be forcibly returned to the Soviet Union, where they faced death or imprisonment.) Even with the Nazis, Churchill longed for the day when Germany could take its rightful place again in the family of nations. At the Tehran Summit in 1943, when Stalin jested about shooting 50,000 German officers once the war was won, and Roosevelt and his son Elliott, who was accompanying him, cordially agreed, Churchill stormed out of the room in disgust. At the grim summit at Yalta in 1945 he said to his daughter Sarah, “I do not suppose that at any moment in history has the agony of the world been so great or widespread. To-night the sun goes down on more suffering than ever before in the World.” His fears of Soviet postwar intentions, especially in Poland, and the apparent indifference of FDR to them, overshadowed his last year in office and even the triumph of victory in Europe.

People who worked closely with Churchill often tried to sum up this splendidly complicated man. One of his secretaries, Marion Holmes, wrote:

In all his moods—totally absorbed in the serious matter of the moment, agonized over some piece of wartime bad news, suffused with compassion, sentimental and in tears, truculent, bitingly sarcastic, mischievous or hilariously funny—he was splendidly entertaining, humane and lovable.

General Alan Brooke, who had been Churchill’s chief military adviser during four years of war and felt that he had not been properly appreciated, wrote, “Without him England was lost for a certainty, with him England has been on the verge of disaster again and again.” Hastings, at the end of his excellent book, does not exaggerate when he concludes that Churchill “was one of the greatest actors on the stage of affairs whom the world has ever known.”

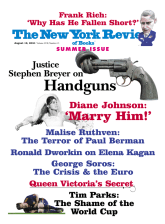

This Issue

August 19, 2010

The Crisis & the Euro

-

1

Of the Quebec conference with FDR in September 1944, Churchill commented sourly on the way home on the Queen Mary, “What is this conference? Two talks with the Chiefs of Staff; the rest was waiting to put in a word with the President.”

↩ -

2

In a new book, Citizens of London (Random House, 2010), Lynne Olsen gives a lively and intimate account of this group at a critical place and time.

↩ -

3

In a forthcoming book, America, Hitler and the UN (I.B. Tauris, 2010), Dan Plesch traces the history of the United Nations Declaration from this event to the end of World War II.

↩ -

4

Carlo d’Este, Warlord: A Life of Winston Churchill at War, 1874–1945 (Harper, 2008), p. 487.

↩ -

5

British supply convoy PQ 16 to Murmansk lost eleven out of thirty-five ships, and PQ 17 twenty-six out of thirty-seven.

↩ -

6

The recently published Churchill’s Bunker by Richard Holmes (Yale University Press, 2010) gives a fascinating history of this institution and much more.

↩ -

7

In Churchill (Viking, 2009), a brief and delightful recent account of Churchill’s life, Paul Johnson estimates that he may have consumed twenty thousand bottles of champagne.

↩