It is easy to underestimate how much fear can obstruct a society’s recovery from horrific violence or repression, or both; and fear now dominates Iraq as its leaders try to make a new start after decades of a ruthless tyranny, its violent removal, and the chaotic aftermath. One principal fear among Iraqis is that there could be a resurgence of the Baath Party and a return to dictatorship. Another is that Iran will dominate Iraq through its influence on Shiites.

Although I found these fears common among politicians when I was in Baghdad in late May, I was caught off-guard when my driver, with disarming earnestness and in the expectation of a simple response, asked me: “Are you sure Saddam is dead? They say they buried wax copies of him and his sons, and that they are living in southern France.”

In Iraq today, conspiracy theories based on what “they say” are so prevalent as to defy straightforward refutation, pointing to a deeper pathology that perhaps only time and genuine reconciliation can cure. For now, such fearful fantasies shape and distort both politics and policies, as the leading Iraqi political parties seek to fashion a coalition government out of the contested results of last March’s parliamentary elections. Every bomb attack, every visit by a political leader to a neighboring capital, every killing of a politician provokes a profound dread that the horrors of the pre-2003 past survive in a diminished but still potent form—whether they derive from the mayhem of the murderous Baathist regime or from Iranian attacks during a senseless war fought more than twenty years ago. Will these ghosts return to leave their bloody mark on the country’s future?

Exhibit A for those terrified by the specter of the Baath’s return was the meeting, set up in April by the Damascus-based branch of the Iraqi Baath Party, of groups opposed to the current order in Iraq. It was the first such gathering that the Syrian regime permitted to take place in public, and the Iraqi prime minister, Nouri al-Maliki, and his Shiite supporters saw it as an undisguised signal that Syria and the remaining Iraqi Baathists were supporting Maliki’s main rival, the former prime minister Iyad Allawi, in his quest to lead the next Iraqi government. Similarly, Allawi, a secular Shiite whose followers are mostly Sunni, cites the post-election spectacle of leading Shiite and Kurdish politicians flocking to Tehran, ostensibly to celebrate Nowruz, the Persian New Year, in late March as convincing proof that the Iranian regime is steering the course of Iraqi politics at their expense.

More than four months since the elections, a new government has yet to take shape. The leaders of the four lists that emerged with the most seats all appear to recognize that the only workable way forward is through a broad-based coalition government. Fearing each other, they all seem to realize that it would be better to be in close proximity, around the table, talking, than in separate corners, out of sight, plotting revenge. In this, they are encouraged by Iraq’s neighbors, as well as the United States, all of whom worry about what might happen if, at this sensitive stage in the country’s development, one party is left out and turns again to insurgency, setting off a new round of civil war with unpredictable consequences for the region.

What is holding things up, however, is the fear among many Iraqis that whatever party wins the right to form the government and appoint the prime minister will proceed to concentrate power around itself, using gaps and ambiguities in Iraq’s new constitution to its advantage. Maliki’s detractors point to his record during the past four years—he has done little by way of concrete governance, but instead has spent much effort to carve out a power base, including setting up security agencies that have no basis in the constitution. In addition to Iyad Allawi and his mainly Sunni constituency, Maliki’s critics and competitors include the Kurds and his Shiite rivals in the Iraqi National Alliance (INA). This last is a loose grouping that includes the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq, the Sadrist movement, and a variety of smaller parties and independents, among them the US’s erstwhile friend and current nemesis, Ahmed Chalabi. Moreover, Allawi asserts that since his list won the most seats—ninety-one, compared to Maliki’s eighty-nine—he has the right to take the first stab at forming a government.

Maliki has questioned the election results, hinting in not so unambiguous terms that a “foreign power”—understood to be the United States—has defrauded him by manipulating the vote, the count, and the recount in Baghdad. Even now, while resigning himself to the decision by the federal Supreme Court to certify the original results in early June, he continues to challenge Allawi’s bid to form the government. His main tactic has been to pursue an alliance with his Shiite rivals in the INA, in order to become the largest bloc in parliament, gain the right to form a government, and thus deprive Allawi of his presumptive right to become prime minister.

Advertisement

Whatever their opinion of Maliki and his autocratic tendencies, Shiite politicians fear most of all losing the position of prime minister, and they are convinced that although Allawi would have a hard time collecting by himself the necessary number of seats (a simple majority of 163 in Iraq’s 325-member legislature), a hidden hand—again, the United States—will somehow assist him and through trickery and deceit cheat the Shiites out of the dominant position they have acquired since 2003, after what they see as the long years of Sunni oppression.

What is striking about the Obama administration’s current approach to Iraqi politics, however, is not its presumed preference for one party, Allawi’s, but its unexplained lack of will to push for a solution, something much noted by politicians of all parties. The US tries to exercise strong influence only sporadically, invariably in the form of a visit by Vice President Joe Biden, the administration’s de facto special envoy for Iraq. He arrived in Baghdad on the eve of Independence Day on July 3 and met with both Maliki and Allawi, as well as other leading figures. The US appears to want the two leaders to establish a broadly inclusive government based on power-sharing, and to do so quickly—well before the Obama administration fulfills its promises to reduce the number of US troops by 50,000 by the end of August.

In public comments, Biden also cautioned his audience against allowing outside forces to set Iraq’s agenda. “You should not, and I’m sure you will not, let any state, from the United States to any state in the region, dictate what will become of you all,” he declared. US commentators pointed at Iran as the intended target, but they could just as easily have mentioned Syria or Turkey, both of which have actively sought to affect the outcome of the current political battle, while Arab states have also tried to exert influence, for example, by warning of the possibility of civil war should Allawi not become prime minister. This should come as no surprise: all of Iraq’s neighbors have a vital interest in the shape it will take. They agree on the need to preserve Iraq’s territorial unity, but disagree on just about every other issue.

This matters all the more since the United States is a fading power in Iraq whose forces are departing and whose diplomacy appears rudderless because its attention is directed elsewhere. In its waning days, the Bush administration signed a Strategic Framework Agreement (the SFA, along with a Status of Forces Agreement, or SOFA) with the Maliki government that was intended to cement Iraq within the pro-US regional orbit. One of the most frequent and most exasperated complaints one hears from Baghdad politicians is that the Obama administration has taken few steps to implement the SFA.

The SFA’s success will depend on two factors: the smooth transfer of some of the Pentagon’s noncombat functions in Iraq to the State Department (such as funding for police training and other civilian reconstruction projects the administration envisions) and the conclusion of a follow-on agreement to the SOFA that will allow the US to maintain control over Iraqi airspace after 2011 while continuing to build up Iraq’s security forces. The US hopes to do this through continued training and other forms of aid, as well as the sale of equipment such as F-16 fighter planes, which are used by other Arab countries cooperating with the US.

Uncertain of what will happen next and what the future US role in Iraq will be, its neighbors are each intent on contriving an outcome favorable to their own interests, and predictably they are working at cross-purposes. Most Iraqis deeply resent the influence these states exert. Depending on where they stand politically, Iraqis tend to cast one of the external forces as the villain while playing down the influence of others. Their perception of interference is magnified by their fear that such foreign meddling will decisively put the party they support out of the game. In Iraq, those who find themselves on the losing side realize that they stand to lose more than their formal positions and their perks and privileges. In the absence of strong institutions, such as an independent judiciary, that would encourage and sustain a peaceful transfer of power, their lives may be at risk as well.

Advertisement

While Iran stands accused of crude interference in Iraq—sending weapons across the border, training Shiite insurgents, funding political activities—its official diplomatic position on forming a government is not only benign but fully in line with that of the other neighbors and, in fact, the United States. Iran’s ambassador, Hassan Kazemi Qomi, declared in April that in his view no single list could form a government on its own and that a coalition agreement among the main four winning lists would be needed. When I met him at the Baghdad embassy, he said that Iran wants Iraq to be unified and stable, free of foreign influence, and flourishing. Without a hint of irony (in view of Iran’s domestic situation), he praised the March elections as a “fair competition with good participation,” and derided the notion that Iran was meddling in Iraqi affairs. Ignoring such Iran-backed Shiite factions as the Kataeb Hezbollah and Asaeb Ahl al-Haq, he claimed that terrorism in Iraq originated entirely with groups, such as al-Qaeda and the former Baath Party, that operate with the support of “Arab states that are friends of the United States.”

Iraqi politicians commonly assert that Iran is pushing for Shiite unity more than for any specific Shiite candidate for prime minister, and Qomi implicitly endorsed this reading when he noted as proof of Tehran’s limited influence in Iraq that it had been unable to achieve the unification of the two Shiite lists, Maliki’s State of Law and the INA. This was an interesting remark, because Iran has been pushing the two groups to join forces for months, starting well before the elections. It has made no progress whatever in the face of Maliki’s insistence that he would have to be the new alliance’s leader, and thus its candidate for prime minister, an outcome that the other Shiite group refused to endorse. For all the talk of Iranian meddling, and despite its strenuous efforts, Tehran has failed so far to accomplish a principal policy goal in Iraq—securing a unified political coalition that could ensure Shiite dominance in Iraqi politics.

Both Iran and other outsiders, including the United States, have had similar failures in the past. In 2008, Iran tried to prevent the US–Iraq security agreements from being signed, and failed, despite its many summonses of Iraqi leaders to Tehran. Worse for Iranian leaders, some of their actions in Iraq have provoked a nationalist backlash from both Sunnis and Shiites. In November 2009, Iran’s speaker of parliament, Ali Larijani, came to Iraq on a visit that many Iraqis perceived as preelection meddling. Among various topics, Larijani raised the issue of dust storms that plague Iran, which he contended originate in Iraq and Saudi Arabia. Instead of expressing sympathy, Iraqi politicians pointedly reminded him of the harmful impact of Iran’s management of rivers that flow into Iraq. Like Turkey, Iran has built dams that sharply curb the amount of water Iraq receives, a pressing concern in the southern marshes, which are drying up as a result. The combination of drought and desertification has given rise to dust storms that make life miserable throughout the region, not only in Iraq. The Iraqis spoke out after months of escalating anger in Basra against Iran’s water policies. These may have wasted much of the goodwill Iran has built up by encouraging cross-border trade and supplying power to cities such as Basra.

If water matters to Iraqis as the source of their civilization and well-being, so does oil, their primary source of revenue. In December 2009, Iranian soldiers occupied a well in the Fakkeh oil field, which is located on the Iranian border in the southern Iraqi province of Meysan; they raised the Iranian flag and claimed the well was on Iranian territory. Outraged, Iraqi politicians asserted that the well had been Iraqi since it was dug in the 1970s. While acknowledging that there is a problem with border demarcation, leaders of the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq, which is often accused of being an Iranian proxy, were particularly angry at the hoisting of the flag, in their view an unacceptable violation of Iraqi sovereignty.

In another example of Iran’s growing influence raising nationalist hackles, inhabitants of the Shiite holy city of Karbala demonstrated in April 2009 against the awarding of a contract to an Iranian company to renovate the historic city center. Karbala is home to two of the most important shrines in Shiite Islam, and the notion that Iran would be in charge of renovation projects was objectionable to many Iraqi Shiites, who view the matter within the context of an age-old competition over supremacy in Shiite affairs between Qom in Iran and Karbala and Najaf in Iraq. The divide between Arabs and Persians continues to interfere with the cross-border solidarity of Shiites.

Turkey doesn’t seem to be faring much better. Turkish leaders are apprehensive of Iran’s growing power in the region, whether by means of its nuclear program or its assertiveness in Iraq. In response, Turkish policymakers have sought to position Turkey as a mediator in the dispute over Iran’s nuclear program, while trying to roll back Iranian influence in Iraq. They make no public declarations to this effect, because they want to protect their otherwise friendly relationship with leaders in Tehran. But they have opened consulates in Mosul, Erbil, and most notably Basra; established a high-level strategic cooperation council jointly with the Iraqi government; and signed a military cooperation accord with Baghdad as well as deals on energy cooperation and water sharing. They are thus giving clear signals that they intend to protect Iraq’s territorial unity by keeping Iraqi Kurds tied to Baghdad, curb Iran’s influence, and gain access to oil and gas, which Turkey needs desperately.

On the political front, Turkish officials privately say that they helped form Allawi’s al-Iraqiya alliance. Whether this is true or not, Turkey clearly believes that al-Iraqiya represents its best hope in Iraq. It is a mostly Sunni list led by Allawi, a secular Shiite whose political views are close to those of the Turkish government and most of the Arab states, all of which are predominantly Sunni and deeply suspicious about the loyalties of Iraq’s Shiite parties, including Maliki’s.

On at least two occasions this spring, Iraq’s Foreign Ministry summoned Turkey’s energetic ambassador in Baghdad, Murat Èzçelik, to tell the Turkish government to stop meddling in Iraqi affairs. Despite Turkey’s active diplomacy and its barely disguised preference for Allawi, however, it seems highly unlikely that he will be able to fulfill his ambition to become Iraq’s first elected, truly secular prime minister. (He served as a US-appointed prime minister in 2004–2005.) And while Turkey has grandiose plans for obtaining energy supplies from Iraq, it frets that Baghdad has failed to move on issues indispensable for Ankara’s prospects, such as a federal oil law.

If neighboring countries have traction in Iraq, it is because the weakness and divisiveness of the frail Iraqi state invite intervention. Yet nearby countries that try to interfere routinely encounter serious obstacles within Iraq, partly caused by what remains of Iraq’s pre-2003 identity, elites, and institutions. Moreover, the same fearful attitude that sees a hidden foreign hand behind every political move also serves to convince a good many politicians that consensus-based politics will help them survive.

Somewhat paradoxically perhaps, the most senior proponent of inclusiveness and national independence is an Iranian-born cleric, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, who has lived in Najaf for most of his adult life. A political quietist by inclination, Sistani has limited himself to laying down basic principles (open elections: good; sectarian revenge: bad), but in doing so has played an important part since the 2003 US invasion in an Iraq ridden with sectarian violence, poor governance, and dysfunctional politics, although his influence now appears to be declining. Revered by the Shiite public, Sistani has also earned the respect of many Sunnis, and politicians have made the trek to his modest dwelling in Najaf to extract a piece of advice, delivered as by Delphic oracle, and often just as ambiguous.

A Sunni politician who visited Sistani along with Allawi and other leading al-Iraqiya figures in May told me that he had come away highly impressed. Sistani had addressed Allawi’s principal fear by indicating that he had no preference for prime minister, as long as the new government would serve the people by improving security, delivering basic services such as electricity, and creating jobs.

Among Iraqis I have talked to, a certain vision survives of Iraq as a cultural middle ground, not a battleground, between Shiite Persia and the Sunni Arab world, a region with lively and diverse ethnic and religious communities tied together historically by the confluence of two major river systems, the Tigris and the Euphrates. You can find many Iraqis who express this sentiment, but somehow I was surprised that one of its most vociferous advocates is a politician of the Sadrist movement, Qusay al-Suheil, a forty-five-year-old parliamentarian from Basra who holds a Ph.D. in geology.

As the followers of Moqtada al-Sadr—a young populist Shiite cleric who comes from a prominent Najaf family that has produced some of the most senior Shiite clerics—the Sadrists are much reviled in the United States for having opposed and fought the American presence in Iraq by one means or another. In anticipation of the US troop departure, they have opportunistically kept one foot in insurgency, the other in politics. Despite the reputation of their militia, the Mahdi Army, as brutish thugs during the bloody street war with Sunnis between 2005 and 2007, the Sadrists emerged in the March elections with forty seats, helped by their clever electioneering and large constituency among Iraq’s urban slum population. Their electoral success has given them a tangible presence in the wheeling and dealing that has defined the past four months. Most importantly, they have been able to keep Maliki off-balance by consistently opposing his bid to remain prime minister. (On July 19, for example, Moqtada al-Sadr met with Allawi in Damascus and remarked on the “readiness” of Allawi’s party “to make concessions.”) If the Sadrists have a political ideology, it is Iraqi nationalism, tinged with the strong conviction that a history of suffering at Sunni hands entitles the Shiites to rule.

Moqtada al-Sadr himself has been pursuing religious studies in Qom, and, in any case, does not seek a formal position of power. In his place, al-Suhail has been mentioned as a possible Sadrist candidate for prime minister (he came in third in an informal Sadrist straw poll a few months ago, ahead of Maliki), although he strikes me as a person better suited to the rough and tumble of parliamentary politics than to managing a country. He has proved thoughtful, though, especially in his insistence that Iraq ought to carve out a space between its two main neighboring powers, Iran and Saudi Arabia. “We seek to provide an equilibrium between them,” he said.

Saudi Arabia and Jordan view Shiites as a homogeneous bloc and as a threat. This is an exaggeration. Iraq has many different ethnic and religious groups, as well as an array of political currents. We have good relations with Iran based on our shared religion—and only based on this. Our Arab bond is stronger than our religious one. We need to go to Arab countries to pierce through these misperceptions.

Others have called for greater economic integration with Iran as a way of keeping the Khamenei regime at bay through entwined interests. Iran is among Iraq’s largest trading partners, and its exports to Iraq already amount to $7 billion per year and are expected to top $10 billion soon. Some two million tourists from both countries—overwhelmingly Shiite—visit each other’s holy sites annually. Compared to Turkey’s three consulates in Iraq, Iran has opened five, most recently in Najaf. Iran also supplies Iraq with electricity, claiming to cover 40 percent of its needs. In return, Iraq provides Iran with some refined petroleum products such as diesel fuel and (smuggled from Kurdistan) fuel oil, as well as crude iron. If Iran’s economic weight surpasses Iraq’s for now, however, this may eventually change in Iraq’s favor; Iraq’s recent signing of a series of contracts with international oil companies to develop the country’s huge oil wealth was the first significant step in that direction.

What is often underappreciated is that, as US forces head for the exit, Iran’s position with respect to Iraq could undergo an important shift. The Iranian preoccupation with convincing the US to withdraw by driving up the cost of an extended stay could be replaced by an effort to fill whatever vacuum the US will leave behind when it does. This will require a constructive—one hesitates to say a “nation-building”—approach on Iran’s part. The question is: Will Washington recognize this and work out a diplomatic and economic modus vivendi with Iran? Apart from Tehran’s intense desire to see the American soldiers leave, Iran and the United States have had a certain commonality of interest in Iraq, from the removal of Saddam’s regime to fair elections that brought Shiite parties to power. But Washington seems as traumatized by past attacks on its troops in Iraq as it is spooked by the Iranian nuclear program and dismayed by Iran’s implacable repression of political dissent.

When I asked Iraqi politicians about Iran’s current approach toward the US, all a parliamentarian from Allawi’s al-Iraqiya alliance could come up with was:

What Iran wants is that no government be formed before August 31, so that it can show to the world that the United States cannot fix Iraq. It is interfering in the political process because it does not want to give the US any opportunity to claim success as it completes the drawdown.

What we now have is a battle of one-upmanship, in which Tehran is trying to give Washington one final poke in the eye as US troops go home, causing, among other things, further delays in forming a new government. Some Iraqis dream of the day they will be in a position to do the poking—in the eye of whichever foreign power has become too meddlesome.

—July 21, 2010

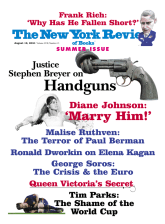

This Issue

August 19, 2010

The Crisis & the Euro