Muriel Spark published twenty-two novels in her lifetime, in spite of beginning relatively late at the age of thirty-nine, and at least half of them are classics by the only criterion that really matters—they invite and reward repeated reading. She was the most original and innovative British novelist writing in the second half of the twentieth century, extending the possibilities of fiction for other writers as well as herself. She had no obvious precursors, except perhaps Ivy Compton-Burnett, and it is interesting to learn from Martin Stannard that Spark was in her formative years an enthusiastic reader of Compton-Burnett—whose work however has a much narrower range of themes and effects than her own.

A truly original writer is a very rare bird, whose appearance is apt to disconcert other birds and bird-watchers at first. I was beginning my own career as a novelist and critic when Muriel Spark began publishing her fiction: in the former capacity I was under the influence of the neorealism of the British “Angry Young Men” era, and as a critic I revered the great moderns like Henry James, Conrad, and Joyce. I was also interested in something called the Catholic Novel, and had written a thesis on the subject. Muriel Spark didn’t fit any of these categories: she was a postmodernist before the term was known to literary criticism, and although she was a convert to the Catholic faith, her take on it was very different from Graham Greene’s or Evelyn Waugh’s. Reviewing The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie in 1961 I declared myself “beguiled…but not really stirred or involved or enlightened.” It was some time before I realized that the disappointment was entirely my own fault and that the novel was a masterpiece.1

There were of course quite enough readers contentedly beguiled by the wit, sharp observation, and refreshing novelty of Spark’s narrative style to make her into a literary star quite soon, especially in America. The New Yorker dedicated almost a whole issue of the magazine to a slightly shortened version of The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, only the second time it had conferred such an honor. Nevertheless (a key word in Spark’s own vocabulary), there was nearly always a significant mutter of dissent and dissatisfaction audible in the general buzz of approbation that greeted each new work, and it grew in volume as she became more and more uncompromisingly experimental in form and content. Reviewing The Only Problem in 1984, Frank Kermode described her as “our best novelist” but added:

Although she is much admired and giggled at, I doubt if this estimate is widely shared. This may be because virtuosos, especially cold ones, aren’t thought serious enough. Another reason is that…Mrs Spark’s kind of religion seems bafflingly idiosyncratic. In fact she is a theological rather than a religious writer.

Martin Stannard quotes this characteristically shrewd observation and his excellent biography helps handsomely to fill out and understand its implications.

The history of this work is itself of some interest. In 1992 Muriel Spark wrote an approving review of the second volume of Stannard’s biography of Evelyn Waugh, and when he thanked her for it she expressed a hope that she would be fortunate enough to find as sympathetic a biographer one day. Stannard tentatively offered his own services, and she invited him to visit her in Tuscany to discuss this “interesting idea.” Soon he was invited to write an authorized biography. No professional (or professorial) biographer could have resisted the opportunity, and he seized it, while wondering why a writer notorious for fiercely guarding her privacy should allow a total stranger to investigate her life without conditions. He was guaranteed independence, allowed to examine freely a huge archive of her papers, and exhorted to “treat me as though I were dead.” Spark had just finished writing Curriculum Vitae, a memoir of her early life up to the publication of her first novel, and Stannard surmised that she had resented the expenditure of time and energy required by this task, and decided to let someone else continue it while she got on with her creative work.

Writing a biography of a living person is always a tricky undertaking, and Muriel Spark was no exception. She had been prompted to write Curriculum Vitae to correct what she regarded as misrepresentations of herself in a book by Derek Stanford, her lover and literary collaborator in the years before she became famous; and, as Stannard would soon discover, she was notorious for making imperious demands of her publishers and frequently threatening to sue others for publishing false reports about her. The pile of documents made available to him proved to contain nothing that was personally revealing, and indeed seemed more like a wall designed to conceal her private life. It was unlikely that such a strong-willed and controlling personality would maintain the promised hands-off stance toward her biography, and so it proved.

Advertisement

Although Stannard has maintained a discreet silence on the subject, it is well known that when Spark read his finished manuscript she declared that it was “unfair” to her and obstructed publication, an obstruction that was not removed until after her death in 2006 by her literary executor. How the dispute was resolved we do not know, but this long-delayed book displays no trace of the frustration its author endured. Its account of Muriel Spark impresses one as both sympathetic and accurate, and it is hard to imagine that it could be improved upon.

Muriel Spark was born in Edinburgh in February 1918. Her father, Bernard “Barney” Camberg, was a Jew; her mother Sarah (“Cissy”) was according to her daughter half-Jewish, with a Christian mother, though the ambiguity of this lineage was to prove a source of much trouble in Muriel’s later years. There is however no reason to doubt her assertion that family life was not noticeably Jewish in matters of diet and ritual observance, that they rarely attended their local synagogue, and that its general ethos was liberal and secular. Socially they were at the top end of the working class, Barney being a skilled factory worker and Cissy the offspring of small shopkeepers in Watford in the south of England. She seems to have been an amiable but rather lazy woman who, Stannard startlingly reveals, consumed a bottle of Madeira every day.

That fact shows they were not poor, but their accommodation was limited: when Cissy’s widowed mother came to live with them Muriel had to give up her bedroom and slept for six years on a sofa in the kitchen. It is hard to imagine a modern teenager putting up with this for six days, but Spark claimed that she suffered no sense of deprivation. She found her grandmother an object of intense interest and helped uncomplainingly to care for her after she suffered a stroke and became bedridden and demented—experience that later bore fruit in Memento Mori.

Neither of Muriel’s parents, Stannard observes, “had the faintest interest in literature,” nor did her elder brother, Philip, who became an engineer. Her own interest was stimulated and fed primarily through education at the James Gillespie School, which she attended from the age of five to seventeen. It was there that she fell into the hands of a teacher called Miss Kay, or as she later wrote, “it might be said that she fell into my hands,” for Miss Kay was the model for Miss Brodie, whose “dazzling non-sequiturs” she would later adapt as a compositional device. She also developed a fruitful friendship with a fellow pupil, Frances Niven, with whom she shared a passionate interest in reading and writing poetry, and made her debut in print at the age of twelve with five poems in an anthology called The Door of Youth. A year later she won first prize in a competition open to all Edinburgh schools with a poem on Sir Walter Scott.

It wasn’t just her family’s limited means that prevented this obviously gifted girl from proceeding to university, for there were scholarships that might have been found for this purpose. Muriel herself had no great urge to do so. She sensed, probably correctly, that the academic study of literature would prevent her from exploring literature in her own individual way, and was anxious to make herself employable in the economically depressed Thirties. So she enrolled in business-oriented college courses in shorthand, typing, and précis-writing, skills that qualified her for a variety of jobs over the next two decades that were not always rewarding in themselves but provided invaluable material for fiction, and probably helped to form her lucid, economical prose style. A few more years of formal education might have saved her from a disastrous marriage, but even that brought her experience she was able to turn to positive account in fiction. As the narrator of Loitering with Intent (1981), Fleur Talbot, declares, “everything happens to an artist; time is always redeemed, nothing is lost and wonders never cease.”

The sexual liaisons and intrigues among the teachers and pupils in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie were, as Spark implies in Curriculum Vitae, a fictional addition to the reality of her schooldays. Edinburgh in the Thirties was an intensely puritanical society, and premarital sex was simply not an option for a respectable young woman. “I never slept with anyone before I got married because no one anyway ever asked me,” she told Stannard. “You didn’t. There wouldn’t have been anywhere to go. I wasn’t in that way of life.”

Advertisement

But she had boyfriends, and to the surprise of her friends and the dismay of her father she accepted at the age of nineteen a proposal of marriage from one of them, Sydney Oswald Spark, who was thirteen years older than herself and whom none of them liked or trusted. He had an MA in mathematics from Edinburgh University, which may have impressed her, and she evidently enjoyed being the object of his infatuation, but if sex was a motive it was probably driven more by curiosity than desire on her part. (She told an interviewer in 1974 that she had rushed into marriage because it was then “the only way to get sex.”)

That “Ossie” as she called him (or later, disparagingly, “S.O.S.”) was a nonpracticing Jew perhaps made him seem a compatible spouse, given her own tenuous sense of Jewish identity; and he offered her an opportunity to see something of the great world, for he intended to go to Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) on a three-year teaching contract. He did not tell her, however, that he had been unable to hold down a teaching job in Scotland and had been seeing a psychiatrist.

Ossie preceded Muriel to Africa, and they were married there in September 1937. The wedding night was inauspicious—“An awful mess. Awful. Such a botch-up,” she commented years later—but she was soon pregnant, and soon aware too of her husband’s unstable character. She responded to the beauty of the landscape and the friendliness of the native inhabitants, but the arrogance and philistinism of white colonial society appalled her, and the increasingly threatening behavior of her husband precipitated a depression after her son Robin was born.

Before long the Sparks were effectively separated. (Coincidentally another future novelist of distinction, Doris Lessing, was going through a similar experience a few hundred miles away, but they were unknown to each other.) By the time World War II broke out Muriel was determined to return to the UK where she hoped to arrange for a divorce with custody of her child, and, after moving to South Africa, leaving Robin in the care of a Catholic convent school, she eventually returned to a war-worn London in March 1944 and joyfully embraced its dangers and austerities (see The Girls of Slender Means). Her familiarity with the novels of Ivy Compton-Burnett sufficiently impressed an interviewer at the Department of Employment to land her a fascinating job with Sefton Delmer’s “Black Propaganda” team inside the Foreign Office, confusing the German population with radio broadcasts that cunningly mixed truth with invention (see The Hothouse by the East River).

When the war ended she sent for Robin, but to her surprise and dismay he arrived accompanied by Ossie, who was uncooperative about a divorce. He had resumed Jewish orthodoxy and Robin, who had reason to feel that his mother had deserted him in infancy, followed his father’s example. Her solution to this imbroglio was to leave Robin in Edinburgh in the care of her parents and go to London to start a literary career. It was, judged by normal maternal standards, a selfish decision, but it was selfishness for art’s sake. Throughout her life she allowed nothing to stand in the way of her vocation as a writer.

For a long time she mistakenly pursued it as a poet, supporting herself in a variety of low-paid jobs associated with publishing and editing, and by producing literary biographies and anthologies, mostly in collaboration with Derek Stanford, whom she met through the Poetry Society. This was a haven for old-fashioned and mediocre versifiers with some of whom she had flirtations and affairs, and with others feuds, when she became the society’s secretary and the editor of its magazine. She was in danger of languishing indefinitely at this genteel end of Grub Street as a minor belletrist, until in December 1951 she won a competition for a short story on a Christmas theme sponsored by the Observer newspaper, which attracted nearly seven thousand entries.

Her story, “The Seraph and the Zambesi,” described an angel gatecrashing a rather tawdry nativity play in Rhodesia in a manner both vivid and matter-of-fact, which Stannard plausibly suggests was the first example of magic realism in British writing. It seems to have been also the first piece of prose fiction Spark wrote for publication, and yet it instantly demonstrated that this—not verse—was the medium in which she could fulfil her artistic ambitions. “The whole tone of the narrative,” Stannard justly observes, “is suddenly lighter than that of the poetry, rippling with crisp, implicit mockery.” She never was, and never would be, a great poet in verse, but her novels and novellas are essentially poetic in style and structure.

This success made her famous overnight, but she did not consolidate it rapidly or easily, for reasons to do with her troubled state of body and soul at the time. Stannard is particularly illuminating on this phase of her life, when she was moving toward Christian faith, first in the Anglican and finally in the Roman Catholic Church, conducting an on-off sexual relationship with the much less gifted Stanford, and trying to write her first novel, while keeping solvent, and her name in the public eye, with literary journalism. She wrote a review of T.S. Eliot’s play The Confidential Clerk that astonished the author with its insight, and Eliot’s praise encouraged her to begin a critical study of his work, but she was overdosing on Dexadrine in order to suppress appetite and work longer hours, which had the effect of making her temporarily deranged, convinced that Eliot’s writing was full of coded threatening messages to her. All these experiences entered into her first novel, including the struggle to write it. The Comforters is about a young woman recently converted to Catholicism who is having a nervous breakdown that takes the form of hearing an authorial voice tapping out on a phantom typewriter a prejudicial description of her thoughts in the novelistic third person. We would learn to call this “metafiction.”

The Comforters was greatly admired when it was published in 1957, especially by Evelyn Waugh, who was struck by its similarities to The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold, which he was currently writing. Graham Greene, who had already been impressed by some unpublished stories he had been shown by Stanford and was generously giving Spark financial help, added his praise. These were the two most distinguished living English novelists at the time, and both Catholic converts. Muriel Spark “completed a grand triumvirate of Catholic-convert novelists,” Stannard declares at the outset of his book; but the Catholicism expressed in her fiction is very different from Waugh’s unquestioning orthodoxy or Greene’s obsession with sin and salvation—it is much more playful, speculative, and unsympathetic to typical Catholic piety. The dogmatic certainties on which the Catholic Novel was based were, however, soon to be called into question by the Second Vatican Council and the emergence of a much more pluralistic Church than the one she originally joined, so her increasingly idiosyncratic Catholicism caused less of a stir than it might otherwise have done. She openly criticized the papacy, for instance, did not attend mass regularly, and always avoided the sermon when she did.

Her attraction to the faith was basically metaphysical: she liked the idea of a transcendental order of truth against which to measure human vanity and folly, and was fascinated by the similarities and differences between the omniscience of God, the fictive omniscience of novelists, and the dangerous pretensions to omniscience of human beings like Miss Brodie. Sub specie aeternitatis human life was not tragic or pathetic, but comic or absurd. “I think it’s bad manners to inflict a lot of emotional involvement on the reader—much nicer to make them laugh and to keep it short,” she told an interviewer in her deceptively insouciant style.

This is what Kermode meant by the “cold” quality of her work. In real life it could be disconcerting: he recalls that she could not see why a party he planned to give in New York in her honor should be canceled because President Kennedy had been assassinated the day before, since “he was only dead because God wanted him.” She was not, however, indifferent to the problem of reconciling the evil and suffering in the world with the idea of God—indeed she considered it “the only problem” in theology. But, drawing on her Jewish heritage, she approached it through the Old Testament rather than the New, especially the Book of Job, where God himself in her view becomes an absurd character.

Stannard sums up the relation between Spark’s metaphysics and her fictional innovations perceptively:

There was human time and there was God’s time. She played with these two spheres of reality: using ghost narrators, revealing endings early to destroy conventional suspense, starting at the end or in the middle, fracturing the plausible surfaces of obsessive detail with sudden discontinuities.

This daring deconstruction of the traditional realistic novel was most extreme in a sequence of short, spare novellas she produced in the late Sixties and Seventies, such as The Driver’s Seat (her personal favorite among her fictions) and Not to Disturb. Among other things they helped to make present-tense narration, hitherto rarely used by novelists, ubiquitous in contemporary fiction. The general public and some reviewers found these books baffling, and she had more commercial success later with novels like Loitering with Intent and A Far Cry from Kensington that drew on her early life to the same droll effect as the early novels.

After scraping through the dreaded test of the second novel with Robinson (1958) she produced, at the rate of one a year, a sequence of scintillating novels from Memento Mori to The Girls of Slender Means, while living in the unfashionable London suburb of Camberwell under the protection of a motherly landlady and making occasional, not very enjoyable duty visits to her family in Edinburgh, who she felt exploited her increased prosperity. It was perhaps partly to put them at a distance that in the late Sixties she based herself for long periods in New York, occupying an office of her own at The New Yorker.2 Later she settled in Rome, where she lived for many years in some style, escorted by a series of ornamental but usually gay or bisexual men. Stannard surmises that she “did not discover their sexuality until too late,” but one feels that, although she enjoyed dressing up glamorously and exerting her spell over men, subconsciously she did not want to be possessed by them and chose her male companions accordingly.

From 1968 onward she became more and more dependent on her friendship with Penelope Jardine, an artist resident in Rome, who acquired a derelict priest’s house and adjoining church in Tuscany and converted them into a home where Muriel eventually joined her, with Penelope, who was fifteen years younger, acting as her companion and secretary. Spark calmly denied they were lesbians, but Stannard says it was love that bound them together. Perhaps “a Boston marriage” best describes their relationship. Muriel bought a series of automobiles in which she enjoyed being driven around Europe by Penelope, who had a fear of flying.

Spark’s later life was marred by illness and painful disability partly caused by incompetent medical care, which she endured with remarkable fortitude. She was less tolerant of what she considered harassment by her son, Robin, who accused her of denying her Jewish lineage and impugning his own by claiming that she was only “half-Jewish.” The issue turned on the exact nature of her maternal grandmother’s marriage, and the evidence, according to Stannard, is capable of different interpretations. Sadly this dispute permanently alienated mother and son and brought Muriel some unfavorable publicity in Britain’s scandal-hungry press, which continued after her death in 2006 when it was revealed that she had cut Robin out of her will.

She was, it must be admitted, a difficult as well as fascinating woman to know personally or professionally. She was mercurial in temperament, restless and demanding, quick to take offense, chameleon-like in appearance, capable (as I found myself on the only occasions when I met her, one weekend in Rome) of seeming to be two different women on successive days. Some acquaintances regarded her as a kind of white witch gifted with preternatural insight. Most found her eccentric and unpredictable, and some thought she was a little mad—an insinuation that, if she ever found them out, would cause their excommunication from her friendship. Some of these character traits also pervade her fiction, which is more challenging than ingratiating. But as the heroine of Loitering with Intent, a portrait of the young Muriel Spark as aspiring writer, observes: “I wasn’t writing poetry and prose so that the reader would think me a nice person, but in order that my sets of words should convey ideas of truth and wonder.” That aim the mature Spark triumphantly achieved.

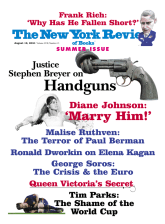

This Issue

August 19, 2010

The Crisis & the Euro

-

1

I tried to make amends in “The Uses and Abuses of Omniscience: Method and Meaning in Muriel Spark’s The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie,” in The Novelist at the Crossroads: And Other Essays on Fiction and Criticism (Cornell University Press, 1971).

↩ -

2

Spark’s special relationship with The New Yorker is usefully tracked by Lisa Harrison in an article, “The Magazine That is Considered the Best in the World,” in Muriel Spark, edited by David Herman (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010), a collection of essays that started life as a special issue of the journal Modern Fiction. The others are mostly interpretative studies in an academic mode, the liveliest and most ambitious being Patricia Waugh’s “Muriel Spark and the Metaphysics of Modernity.”

↩