1.

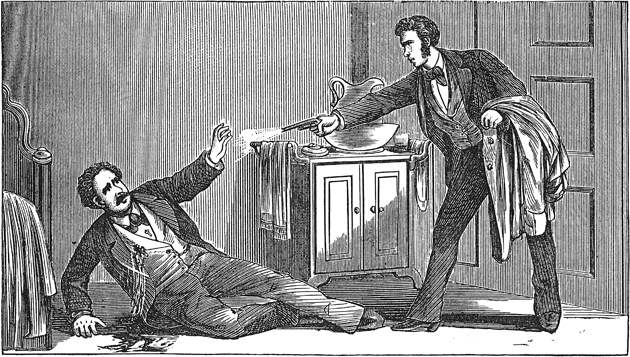

Geoffrey O’Brien’s delicious and deceptively intricate The Fall of the House of Walworth, a true-crime “tale of madness and murder,” offers a new twist on the Gothic strain in American life and literature. Edgar Allan Poe, who wrote “The Fall of the House of Usher,” might have admired it. On June 3, 1873, Mansfield Tracy Walworth of Saratoga Springs, author of the sensationalist novels Warwick and Delaplaine—books so atrocious, so full of “lost wills, men in black masks, treasure hunts in the Amazon jungle, mystical Hebrew inscriptions,” that even their publisher refused to read them—was gunned down in a Manhattan hotel room. The polite young murderer made no attempt to flee, insisting instead on punctiliously informing the police and the hotel staff of his deed. It was his “coolness,” reminiscent of one of Poe’s calculating criminals, that the reporters who flocked to the scene insisted upon. “This was,” in O’Brien’s summary of the newspaper accounts, “a disturbingly modern crime, in a modern hotel, committed by a modern kind of youth—refined, stylish, in some accounts irresistibly attractive.”

The crime was rendered more piquant by the identity of the killer, for nineteen-year-old Frank Walworth happened to be the slain novelist’s eldest son. His parents, moreover, were stepbrother and sister, lending a hint of incest to the unsavory proceedings. If there was a motive to the parricide, it seemed to center on certain threatening letters, remarkable for their deranged cruelty, written by Mansfield Walworth to his estranged wife, Ellen Hardin Walworth. “A sustained howl fusing obscene insult and self-pitying melodramatic soliloquy,” these letters, as O’Brien notes, seemed lifted from one his own novels. “I am a hungry demon,” he wrote in one of them, “and I am longing to lap my tongue in salt blood.” The letters were sometimes accompanied by bullets and packets of gunpowder.

Stumbling across this correspondence, much of which was read aloud in the aghast courtroom, a loyal son might reasonably feel called upon to protect his endangered mother, a touch calculated to appeal to an audience (and perhaps a jury) of readers of the sentimental fiction of the time. “Mother love,” O’Brien observes, “was the central shrine of American sentimentality” during the nineteenth century. The accused murderer’s own peculiar behavior preceding the murder, reportedly including epileptic fits and catatonic trances, provided the basis for an alternative defense of insanity.

As the trial ebbed and flowed between these conflicting narratives, some of the most skillful lawyers of the time laid out their own high-flown versions of what might have led to the murder in the hotel room. On the question of whether Mansfield Walworth’s many misdeeds should be taken into account in the verdict, a key component of the defense, the prosecutor asked, rhetorically, whether the crier of the court should call Mansfield to the witness stand:

Oh, gentlemen, he may call, and call again, but from that shattered jaw, that pierced heart no answer shall ever come from this side of the grave, and he shall never tell that story until he tells it before that awful bar where no secrets are hid and where no judgment can annul.

The trial occurred, O’Brien observes, during a particularly volatile period in American history, after the national trauma of the Civil War had swept aside so many antebellum institutions and assumptions, inaugurating what Mark Twain sardonically called a boom-and-bust “Gilded Age” rather than a golden one. Attorneys at the Walworth trial had to wrestle with a new definition of first-degree murder (perpetrated with “deliberate and premeditated design”), lingering questions about the efficacy of the death penalty, and “expert” opinion regarding the causes and nature of mental illness. Fine points of jurisprudence tended to get lost, however, in feverish newspaper accounts of the highly publicized trial. As it turned out, Frank was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison. He did time at Sing Sing and at the prison and asylum in Auburn and, four years after the trial, following constant pleas by his mother, was pardoned by the newly elected governor of New York.

2.

If Gothic fiction, with its habitual blurring of the living and the dead, tends to thrive in locales of rapid change, where one form of life has only partially supplanted another, nineteenth-century Saratoga seemed particularly ripe for ghosts. The sleepy village with its “foul-smelling waters” was reinvented by midcentury as an upscale resort. Horse racing and gambling were introduced during the Civil War, inaugurating “a new and rowdier era.” Saratoga rapidly became “a place of national importance,” O’Brien notes, “in a nation short on gathering places for people from different regions.” The spa was particularly alluring for Southerners, “a perfect spot for cementing the business relationships that encouraged a wide tolerance for slavery among New York merchants and industrialists.” Several generations of Walworth men married Kentucky women; much of the dynamism of The Fall of the House of Walworth comes from this North–South interplay.

Advertisement

The “quaint and equivocal appellation” of the House of Usher denominated, according to Poe, “both the family and the family mansion.” Similarly, the House of Walworth, in O’Brien’s own neo-Gothic narrative, refers both to a particular mansion on Broadway, the main thoroughfare, then and now, in Saratoga, and to the Walworth family. When the story opens, in 1952, the Walworth mansion, known as Pine Grove, has become a haunted house “thick with ghosts,” shorn of its protective pines, and filled with the wreckage of its lost grandeur.

Its lone inhabitant is a woman of sixty-five named Clara Grant Walworth, the last of the Walworths. Daughter of a murderer and granddaughter of his victim, she lives out her Miss Havisham–like existence:

Her role, all her life, had been to preserve and remember. A votary in an abandoned temple, she had been born to go through every scrap of paper, rummage in every drawer, make lists of relics left behind. The house was her museum; her mausoleum, finally. She had been buried here, together with all she loved, for as long as she could remember.

Of course, Geoffrey O’Brien himself is something of a votary in this mausoleum-museum. A poet, astute cultural historian, penetrating music critic, and editor in chief of the authoritative Library of America editions of American literature, O’Brien has written incisively on the 1960s, another period of wrenching social change, in his superb book Dream Time. If his considerable erudition is held in check in The Fall of the House of Walworth, the reason is not because he wants the book to “pass” as a piece of popular true-crime entertainment, like The Devil in the White City (another tale of “murder” and “madness”) or Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil. I think his primary aim in this new book is analytic, to explore, in the way that his own self-effacing masters, Poe and Flaubert, might have done, the emotional and rhetorical excesses of a particularly interesting time in American history. By the end of the book, the reader may well wonder whether the “madness” of his subtitle is inherent in the Walworth genes or whether it is somehow latent in American society itself.

For O’Brien, three generations of Walworths represent, on the face of it, a steady decline like Thomas Mann’s Buddenbrooks, ending in murder and mayhem. The great man of the family, the rich and well-connected Reuben Hyde Walworth, is “an institution in himself”; he presides over the idiosyncratic Court of Chancery, concerned with wills and property rights, “a judicial domain in which he enjoyed something like absolute rule,” in the parlor of Pine Grove. On closer scrutiny, however, the “fall” of the Walworths seems to begin with the Chancellor himself. Seemingly the embodiment of dignified authority, he has a tendency to get lost in details and digressions in ways that sound, according to O’Brien, like “the symptoms of a neurological disorder.”

O’Brien’s portrait of the great man at work has a comedic verve reminiscent of Dickens or Melville:

He had always exhibited a capacity to feed on material that to others was the very essence of tediousness. An acquaintance said he had “little susceptibility to poetry,” but to him poetry may have resided precisely in the fine print of deeds, wills, and contracts. At any rate nothing deterred him from proceeding tirelessly with the work before him. Yet it did seem that, for all his labor, the pile of unfinished business never got any smaller. In fact the more he worked, the bigger the pile got: there were six hundred causes in arrears while his decision remained pending. The word got around that his courtroom was a place not to resolve business but to be kept forever waiting for the resolution that never came.

Perhaps wisely, the state abolished the Court of Chancery in 1848.

The Chancellor’s second marriage, with the widow Sarah Hardin, in 1851, seems to have satisfied both of their needs—autumnal companionship for him and a public stage for her. (She was out riding with her friend and cousin by marriage Mary Todd Lincoln when they heard the news of the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter.) The marriage of their respective children, Mansfield Walworth and Ellen Hardin, attended by Washington Irving and William Seward, was founded, at least for Mansfield, on fantasies of Southern romance and Catholic ardor. It was a predictable disaster from the start. As his paranoid possessiveness escalated—“Manse is so sensitive of me being seen, especially by young men”—Ellen spent more time in Kentucky raising their many children. Mansfield rented rooms in New York and pursued his literary career. One of their sporadic attempts at reconciliation ended when he dragged her into the “bedroom, smashing her repeatedly against the furniture, finally ripping her clothes off.” At one point, in a rage over their unsettled living arrangements, he bit her finger to the bone.

Advertisement

At the center of Mansfield’s novels, there was always a man of great physical beauty whose supreme gifts the world refused to appreciate. Around these wishful self-portraits, Mansfield created tangles of intrigue, betraying, according to O’Brien, “a staggering slovenliness about pulling together the details of his fictional world.” The plots of these serpentine novels beggar belief, as with O’Brien’s summary of the opening of his last novel, Married in Mask:

Abandoned children inhabited a labyrinthine hideout constructed within a manure heap not far from where the docks went up in flames. A detective spent twelve years searching for an abducted girl who would finally be impersonated by an actress when the time came for her testimony at the murder trial of an Italian foundling who had, somehow, become the son-in-law of New York’s most famous and most reclusive financial genius. The girl had by this point in the novel been abducted not once but twice, leaving behind two quite different sets of inconsolable parents, while in the meantime crucial evidence had been destroyed in two quite separate dock fires. The missing link between a sordid waterfront knifing and the apparition by the millionaire’s bedside at midnight of a masked burglar not more than twelve years old would turn out to be the abortive struggle of Venetian patriots against Austrian oppressors.

One could almost predict that Mansfield, with his Kentucky in-laws and his romantic flair, would run amok during the Civil War. Through his father’s influence he was granted a sinecure dealing with military communications in Washington. “He seems,” as O’Brien dryly puts it, “to have had difficulty keeping such information to himself.” With his “characteristically elusive” loyalties, Mansfield apparently offered his services as a spy to both sides, outfitted himself with a Confederate uniform, and embarked on an affair with a Confederate agent named Augusta Morris, in whose bed he was arrested by Allan Pinkerton’s secret service agents. From his prison cell, he wrote to his wife, with the “grandiloquence of his fictional heroes,” of his own cruel fate: “I have struggled hard but it seems in vain.”

During the war, the Kentucky-based Hardins, women and men, comported themselves far more impressively than the slightly ridiculous Walworths. Kentucky was a fiercely contested border state, and its citizens were faced with a difficult choice of allegiance. Hardins had fought and died in the Mexican War, and Ellen’s brothers fought, with distinction, on both sides of the Civil War. General Martin Hardin led a Northern regiment at Gettysburg and lost his left arm to Confederate raiders in Virginia. His brother Lem harassed Union forces in Kentucky and Indiana, received a bad leg injury late in the war, and escaped to Canada dressed, with Ellen’s help, in women’s clothes.

Meanwhile, the civil war among the Walworths intensified after the Chancellor’s death in 1867. Mansfield’s older brother, Clarence, having betrayed no emotion more wayward than a fashionable susceptibility to Cardinal Newman’s return to the pomp and ritual of Rome, was made executor, and in charge of disbursing funds to Mansfield as he saw fit. The night of the great man’s funeral, O’Brien reports, Mansfield was so indignant at the humiliating terms of the will that he “got drunk and tried to break into the sleeping quarters of the local female seminary.” Feeling persecuted by his family, especially Clarence and Ellen, whom he believed were in a conspiracy to destroy him, Mansfield began sending his threatening letters, often two or three a day—letters that prompted his eldest son, the young and unstable Frank Walworth, to take matters into his own hands.

3.

O’Brien’s Gilded Age is a cacophony of competing rhetorical registers, each of which seems designed to drown out any recognizable human reality. The high-flown verbiage of the courtroom, of the church (in both its respectable denominations and its more exotic varieties, particularly rampant in upstate New York), of the political world, of the sensationalist press and the even more sensation- alist fictional realm—how could one keep one’s balance in such a furor? Rather surprisingly, Frank, of all the Walworths, seems to have made perhaps the smoothest adjustment to a new age.

After his pardon, he shed his traumatic past like an old skin. He took up the newly fashionable sport of archery, not as an idle hobby but to the point of mastery, offering technical advice to aspirants. Success at the difficult sport, he maintained loftily, came not from constant practice but to “him who cares to bring his intelligence to bear upon his pastimes.” In 1881, barely four years after his release, he was awarded first prize at the national archery tournament in Brooklyn. He also became interested in bicycling, another rage of the Gilded Age fitness craze, and contributed articles to Bicycling World and American Wheelman. And then, as though picking up a thread of the family inheritance dropped for a generation, Frank married the daughter of the governor of Kentucky and embarked on a legal career—the Chancellor would have approved.

All of O’Brien’s characters seem, like Don Quixote or Emma Bovary, bewitched by books, trying to enact dramatic plotlines in their lives despite the stubborn recalcitrance of their everyday reality. What O’Brien says of Ellen, that “nothing was quite real until it had been described in a book,” could apply to all of them. There doesn’t seem to have been a Walworth who didn’t write. Mansfield wrote his novels; Frank wrote Byronic poetry as well as his articles for the sporting world; Ellen wrote histories of Saratoga and a failed novel about “the life of a noble woman who makes the best of the vicissitudes that encompass her”—an idealized version of herself; Clarence and the Chancellor wrote histories of the Walworth family. Even Ellen’s precocious teenage daughter Nelly, carted off to Europe with Uncle Clarence to distance her from the publicity of the trial, wrote letters home that, edited by Ellen, became a popular travel book called An Old World Seen Through Young Eyes.

As the turn of the century approached, Ellen Walworth came to regret the passions of her youth; she longed for something more reliable than literary fantasies. One sympathizes with her efforts to identify “a world of clarity and sanity, a rational order.” After her intense efforts to get Frank pardoned, she took an interest in the preservation of battlefields and the homes of great men. Appalled by what she called the “bombast and folly” of Fourth of July celebrations, “all that noise and nonsense,” O’Brien notes, “that had emanated, although she did not say so, from men,” she and two other women founded a new organization devoted to a more sober patriotism, the Daughters of the American Revolution. “The esprit de corps” of the DAR, she insisted, “is to be national, as it is in the army and navy.” During the Spanish-American War, she was named director of the Women’s National War Relief Association. One can see how such bureaucratic activities might have served a therapeutic purpose, to build a psychological moat around the turbulent passions of her own chaotic family.

O’Brien’s mainly sympathetic portrait of Ellen recalls at times Lytton Strachey’s somewhat more ironic account of Florence Nightingale in Eminent Victorians. In the case of both women, there is a conspicuous gap between public-spirited saintliness and carefully hidden inner conflict. O’Brien contrasts Ellen’s widely quoted pronouncements—“Your child will not be a good workman, a good citizen, a good soldier if he is not trained to obey”—with the gloomy desperation of her intimate journal: “I cannot work. I cannot think—there is only the intense desire to get through with what is necessary—and to lie down and die.” At such moments, when even the intrepid survivor yields to morbid disillusionment, the fall of the doomed Walworths seems at last complete.

Henry James once complained that Flaubert’s exquisitely written books were short on appealing characters: “Why did Flaubert choose, as special conduits of the life he proposed to depict, such inferior and…such abject human specimens?” James seems not to have noticed that the lives that Flaubert, the son of a physician, “proposed to depict” were lives infected with romantic illusions, which the novelist sought to cure with his own dry irony. Some readers may wish for someone more alluring than the founder of the DAR or the winner of the national archery tournament in Geoffrey O’Brien’s blighted company of murderers, madmen, and sanc- timonious bureaucrats. Mightn’t the Hardins have been accorded more room in the book? But that would be to mistake the genre he is writing in, and the complicated game he is playing. Just as Madame Bovary is both a romance novel and a lucid critique of one, Geoffrey O’Brien’s vivid and multilayered book, with its many Gothic touches and its remarkable reconstruction of family history, is an immeasurably more sophisticated example of precisely the kind of sensational crime fiction and fantasy he has set out to understand.

This Issue

August 19, 2010

The Crisis & the Euro