It wasn’t even a blip on the evening news but early this summer, in a display of fancy footwork on the diplomatic high wire, Barack Obama came close to mentioning in public a subject on which every president since Lyndon Johnson has been strictly mum: the fact, unacknowledged for more than four decades now, that the United States knows Israel has nuclear warheads. On the basis of a secret “understanding” struck by Richard Nixon and Golda Meir in 1969, the established practice has been to abide by Israel’s policy of maximum coyness and ambiguity on the subject even when—or especially when—it conflicts with Washington’s long-flaunted goal of pressing aspiring nuclear powers that long ago signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, like Iran, for example (under the Shah), or Iraq (before Saddam Hussein), to abide by it and allow international inspection of their nuclear facilities.1

Israel is a nonsignatory and not the only one that Washington finds it inexpedient to press, just the only one on which it has maintained a vow of silence. India, thanks to the last Republican administration, now gets the sort of American help building reactors from which it was supposed to be forever barred as a result of its decision to go nuclear. Pakistan—arguably the worst proliferator on record, having boosted the nuclear programs of Libya, North Korea, and Iran—is one of the largest recipients of US military assistance because its cooperation is deemed indispensable so long as we’re fighting next door in Afghanistan. It’s a hard world out there and policy contradictions are not easily avoided; sometimes influence has to be bought. So goes the thinking of so-called “realists” in foreign policy circles.

New to office, Obama determined to put life and muscle into the flagging nonproliferation drive, in part to justify the effort to squeeze Iran and keep it from going the way of North Korea, and, in the much longer run, to work toward regional agreements that might eventually include the Middle East. So, when after four weeks of discussion, a UN conference of 189 nations reviewed the nonproliferation regime and reached a twenty-eight-page agreement on new steps to be taken toward halting the spread of weapons and promoting peaceful uses of nuclear energy, the Obama administration hailed it as “forward-looking and balanced.”

There was, however, a catch, making fancy footwork by the President unavoidable. The agreement his administration had hailed in May didn’t mention Iran, which had attended the conference, its delegation headed briefly by President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. But it did mention Israel, which had not, calling on it to sign the nonproliferation treaty and take part in a conference in 2012 on turning the Middle East into a nuclear-free zone. Lurking between the lines seemed to be a wispy hope that Iran might be persuaded to forswear nuclear weapons if Israel could be drawn into discussion of the circumstances under which it might consider giving up the two hundred or so nuclear warheads it has long been rumored to possess. Who then was being squeezed and how could the United States, which had yet to acknowledge Israel’s nuclear status, dance around that tangle at a time when it was simultaneously trying to mend fences with the right-wing government of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and persuade it to get serious about peace talks with the Palestinians?

Netanyahu was standing next to the President at the White House on July 7 when, speaking elliptically, carefully avoiding words like “nuclear” or “weapons,” Obama came closer to an on-the-record acknowledgment of the Israeli deterrent—and, by any reasonable reading, putting an American stamp of approval on it—than the previous eight presidents. (A quickly corrected verbal slip left a lingering impression that the President privately understood that Israeli weapons might also serve American interests.) Here is his actual language:

We strongly believe that given its size, its history, the region that it’s in and the threats that are leveled against us—against it, that Israel has unique security requirements. It’s got to be able to respond to threats or any combination of threats in the region. And that’s why we remain unswerving in our commitment to Israel’s security. And the United States will never ask Israel to take any steps that would undermine their security interests.

Dan Meridor, a deputy prime minister to Netanyhu, instantly interpreted this as an endorsement of Israel’s policies and, therefore, an assurance that Washington would not press Israel to sign the nonproliferation treaty it has refused to sign for forty years. “I think this entire presentation,” Meridor told Reuters, “gives a clear picture of the understanding between Israel and the United States.”

Advertisement

In other words, gotcha. The United States might now be on record as favoring the transformation of the region into a nuclear-free zone but it was simultaneously on record as saying this could happen only after the dawning of a peace so profound that its one existing nuclear power felt secure enough to surrender its arms. Which was what everyone who has thought about the matter for more than three minutes had assumed before the conference Obama had championed. If American non-proliferation policy was not exactly contradictory, when translated into plain language, its logic was strained and its practical application obscure.

For students of such issues, there is nothing new in the idea that the line between diplomacy and hypocrisy can be a fine one; that nations can have conflicting goals, especially nations playing for high stakes by holding or seeking nuclear weapons. Israel itself is not exactly pure in this arena, as we are reminded by The Unspoken Alliance, a survey somewhat undersold by its subtitle: “Israel’s Secret Relationship with Apartheid South Africa.” What makes the book, written by a young editor at Foreign Affairs, more than a little tantalizing isn’t its account of Israel’s readiness—sometimes even eagerness—to soften its stand on the apartheid regime’s race policies and, overlooking a United Nations embargo on arms sales to South Africa, find a rich market for its own growing arms industry. It’s the flashes of new insight it provides on the extent of nuclear dealings between embattled Israel and a pariah state whose circumstances increasingly could be said to parallel its own.

Sasha Polakow-Suransky took advantage of an enlightened freedom of information act passed in the liberal atmosphere that existed in South Africa in the first flush of majority-rule government. Despite formal representation by Israel that the release of the classified documents he sought might compromise its national security, he procured more than seven thousand pages from the defense and foreign affairs ministries in Pretoria, now under the control of an African National Congress with few reasons to fret about the sensitivities of the apartheid government’s silent partner. He doesn’t tell us how many of these pages really sizzle but he provides a list of aging officials he interviewed from the old days of white rule who once knew the details of their country’s effort to go nuclear; he met them over coffee in suburban malls, on their farms, or in assisted living quarters. These included a long-time defense minister, General Magnus Malan. The son of South African Jews, Polakow-Suransky made similar efforts in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv but, not surprisingly, got no documents and, especially when it came to nuclear issues, more guarded responses there.

The documents—the presumably small portion of the seven thousand pages dealing directly with nuclear issues—don’t convict Israel of nuclear proliferation to South Africa (notwithstanding a sensational report in the Guardian on May 24 asserting that “Israel offered to sell nuclear warheads to the apartheid regime,” based on this material). But they can hardly be said to fully exonerate Israel on the proliferation charge, as South Africa’s last white president, F.W. de Klerk, dutifully tried to do in March 1993 in the usual elliptical language, a year before the handover of power and two years after South Africa, under American prodding, finally signed the nonproliferation pact.

Acknowledging for the first time that South Africa had developed nuclear weapons, de Klerk said that they had now all been dismantled under international inspection. “At no time did South Africa acquire nuclear weapons technology or materials from another country, nor has it provided any to any other country, or co-operated with another country in this regard,” he said without once mentioning Israel, the only possible supplier that there could have been reason to suspect.

It’s the last clause of that sentence that appears to be undermined by the incomplete evidence Polakow-Suransky has managed to unearth. Citing an interview with the manager of the plant where the South African warheads were manufactured, he tells us that it wasn’t only the weapons that were destroyed but “all proliferation-sensitive records associated with the program.” De Klerk’s assurances, he says, “artfully sidestepped the truth” and used “clever semantics” to obscure the cooperation that did occur. (The suggestion, attributed in a footnote to the plant manager, was that Israel was careful to cover its tracks by providing what were arguably “dual-use” technologies with peaceful applications, though it was fully aware, on the basis of extensive military and scientific exchanges, of the real nature of South Africa’s interest.)

This was nothing so crude as an offer to sell warheads but Israel was deep into a shadowy area where the exact location of the line between proliferating and not proliferating could be hard to draw. Like a driver going ten or fifteen miles over the speed limit, Israel’s main concern, it seems, wasn’t to abide by the law but not to get caught—in this case, by its primary ally, the United States.

Advertisement

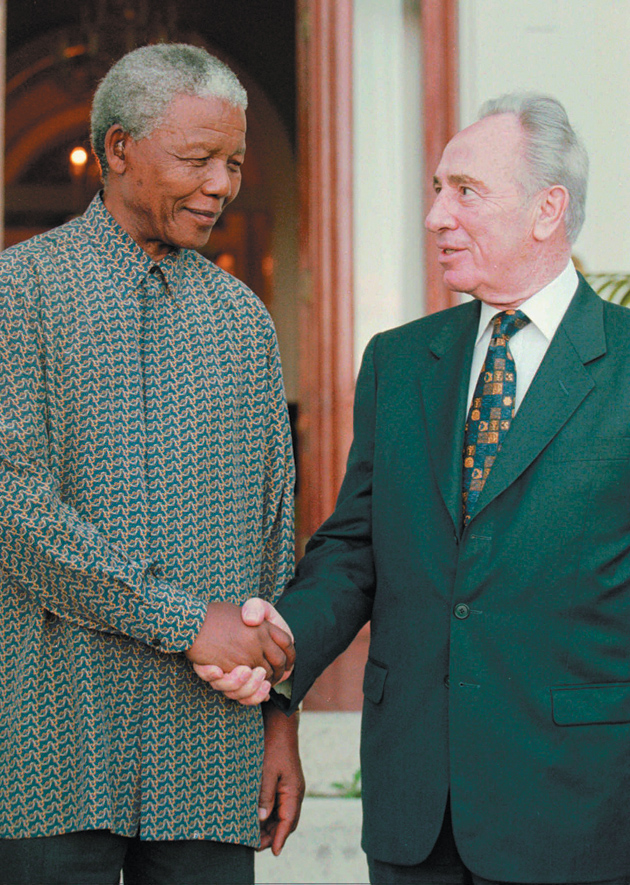

It’s possible but unlikely that American officials got a glimpse of any “proliferation-sensitive records” that may have been destroyed by the old management in Pretoria. From the start of Israel’s serious military engagement with South Africa, secrecy was the name of the game. It was also a fundamental principle of the first formal agreement, a pact signed in April 1975 by P.W. Botha (the future South African president, then defense minister) and his Israeli counterpart, Shimon Peres (a future prime minister and, now, a president himself). As summarized in The Unspoken Alliance, the agreement provided that it would remain in force indefinitely and couldn’t be terminated unilaterally by either country. “It is hereby expressly agreed,” it said, “that the very existence of the Agreement…shall be secret and shall not be disclosed by either party.”

Polakow-Suransky isn’t the first to write about nuclear collaboration between the two countries, let alone their widening arms trade and intelligence cooperation over the next decade and more; or Israel’s readiness to help Pretoria evade the arms embargo by serving as what amounted to a beard; or about consultations between the two governments that eventually reached the subject of domestic security, in which they compared notes on ways of suppressing the insurgencies they faced. (Seymour Hersh, for one, delved into the nuclear side of the expanding relationship in The Samson Option, his 1991 book on Israel’s nuclear program.) But he’s the first to uncover the actual agreement Botha and Peres signed, showing that the UN Special Committee Against Apartheid was more right than it could have known when in 1983 it outraged Israel’s supporters by sponsoring a conference in Vienna on “the alliance between Israel and South Africa.”

The discussion the Guardian seized on dealt with the sale of Israeli-made medium-range missiles, given the biblical name of Jericho, capable of carrying nuclear as well as conventional warheads. From Polakow-Suransky’s account, the two sides seemed to be feeling each other out in an exploratory talk, preliminary to any hard bargaining on the details of their cooperation. Israel—shaken by its huge losses of troops and matériel in the first phase of the 1973 Yom Kippur War and Washington’s initial hesitation in sending an air armada on a resupply mission—had determined that it would have to get into the production of sophisticated arms on a scale well beyond its own means. It was looking for customers with big pockets who might invest in costly programs like the Jericho. South Africa, shaken by the impending Portugese withdrawal from Angola and Mozambique, was steeling itself for confrontation with liberation movements on its own borders. It had an embryonic nuclear program underway but had not yet committed itself, strategically or financially, to the goal of becoming a nuclear power. Still, it was interested. The weapons would have to come with “the correct payload,” Botha told Peres.

Peres responded like a salesman unpacking his samples kit; in the words of minutes of the meeting on file in the South African National Defense Forces Military Intelligence Archive, he said: “The correct payload was available in three sizes.” There is no corroborating Israeli document on public view and, even if there were, there’s no way to measure Peres’s real intentions at this early stage of the discussions. While it’s possible to imagine Pakistan’s supposedly renegade nuclear huckster A.Q. Khan flashing a similar come-on to Muammar Qaddafi in Tripoli, in this case the Israelis’ apparent offer wasn’t put to the test. The South Africans weren’t ready to put up the money. On the basis of the evidence he presents, Polakow-Suransky seems to overstate the case when he refers to it as an “abortive deal.” There was no deal, just a conversation. It’s the difference between conception and a gleam in the eye.

In the context of present-day discussions of proliferation, it’s not exactly irrelevant to mention that a market-hungry Israel then carried its proposal for missile cofinancing to the Shah’s Iran where agreement was struck on a short-lived project code-named “Flower” (a forerunner, it might be suggested, of the reckless maneuvers that came to be known as the Iran-contra scandal, in which Israel and the Reagan administration plotted to reengage revolutionary Iran by selling it arms).

The first South African purchases from Israel, meanwhile, were not reach-for-the-stars stuff but standard military hardware: ammunition, tanks, and tank engines. However, the story doesn’t end there. It continues into the last decade of the apartheid regime. With the fall of the Shah, the Israelis were once again keenly interested in South African partnership on missile technology. Magnus Malan and other high military officials in Pretoria were invited to witness tests of a new, improved Jericho missile over the Mediterranean. By 1984, the two governments reached agreement on coproduction of the Jericho 2, which had three times the range of the original, and on joint testing from the Overberg Test Range on the Cape of Good Hope, where rockets could be fired off into the South Atlantic with less risk of discovery. During this period, Polakow-Suransky tells us, seventy-five Israeli rocket specialists were stationed at the Cape, while more than two hundred South Africans were sent to Israel for training. The tide of expertise was clearly flowing north to south, from Israel to South Africa.

“They were able to develop their own military industries by using our know-how and our expertise which we sold sometimes, I thought, too easily,” a former head of the Israeli military mission in Pretoria remarked to the author. “But we did because we were very much in need of this relationship.” This official, once the commanding officer of Israel’s navy, wasn’t referring specifically to know-how on missiles and warheads. But his words may apply there too.

When the administration of the first President Bush eventually asked its ally in Jerusalem whether there had been a transfer of missile technology to South Africa, it got less than a straight response. (The Central Intelligence Agency, we’re told here, strongly suspected it knew the answer, which was why the question was being put.) Israel said merely that it had made a decision after the United States imposed sanctions on South Africa in 1987 to refrain from engaging in any new arms deals with Pretoria. It failed to mention that an agreement on missile cooperation had been signed three years earlier and was still in force. By this point Israeli diplomats and analysts well understood that the writing was on the wall for white rule in South Africa. But Israeli generals and security officials clung to the relationship—and to their access to the test range—to almost the last possible hour.

By the time the missile accord was finally struck in 1984, South Africa had produced its first nuclear device. The idea was never to hurl a warhead into Luanda, Lusaka, or Maputo. It was a card to be played in trying to persuade Western powers not to “abandon” the regime in the face of a Communist “onslaught.” But when the curtain rose for the last act, South Africa’s undeclared nuclear status proved to be less powerful than the political pressure for sanctions brought to bear in the West by the anti-apartheid movement; nor could a nuclear arsenal do anything to slow the breakdown of the racial order increasingly evident in the industrial belt around Johannesburg. The end of the cold war shredded the always feeble argument that the white regime might have some residual value as a strategic partner.

When the relationship first got serious, back in the 1970s, Israel had already been a fully fledged, though unacknowledged, nuclear power for at least six years. South Africa didn’t build its first nuclear device until seven years after the Botha–Peres talks. Could it have progressed that fast without outside guidance and advice? Any answer to that question must be speculative but it’s not a great stretch to imagine that there was some payback for Israel’s access to South Africa’s vast mineral resources and open spaces.

Polakow-Suransky cites several indications that the two countries were continuously engaged on nuclear issues. Shortly after the Botha–Peres meetings South Africa removed restrictions that had been placed on five hundred tons of “yellowcake”—a compound suitable for enriching to weapons-grade uranium—that had been shipped to Israel under a secret agreement that the ore was to be stockpiled and inspected annually in the Negev by the South African Atomic Energy Board. In exchange, Israel shipped South Africa thirty grams of radioactive tritium, a substance, according to the Federation of American Scientists, that’s “essential to the construction of boosted-fission nuclear weapons” (in which tritium and deuterium are heated to the temperature and pressure required for nuclear fusion, making the bomb more powerful).

Finally there was the once-notorious double “flash” over the South Atlantic in 1979, which an American surveillance satellite recorded and instantaneously relayed as a presumptive nuclear test. The Carter administration came down hard on Pretoria, only to back off when further scrutiny of the evidence led to the conclusion that the test was more likely to have been carried out by Israel with the connivance and assistance of South Africa. “Overnight, just like that, the pressure disappeared,” a former South African official recalled in an interview for this book. It was one thing, it seems, to be seen as pushing South Africa on a nuclear issue; quite another to make it an open issue with Israel, whose status as a nuclear power Washington resolutely declined to acknowledge. That could only undercut the official American stand on nonproliferation. Which is where we came in.

The threads of the nuclear relationship that The Unspoken Alliance traces stand out because of the new material its author has dug up, which may be deemed to provide a measure of insight into ongoing and tricky proliferation issues. But those threads represent a relatively small part of the broader narrative Polakow-Suransky stitches together, which aims to set the hidden relationship between two beleaguered states in its full geopolitical and domestic settings. He capably, sometimes breezily, delves into Israeli and South African politics. In his assessment, it’s the Israelis who come off worse on any scale of hypocrisy, especially those who’d indulged in denunciations of apartheid with a “light unto the nations” fervor. Shimon Peres, the wheeler-dealer who served as David Ben-Gurion’s right hand on arms procurement before stepping into the political limelight himself, takes a bigger beating than P.W. Botha for his “customary sanctimony.” In private, he could laud South Africa’s white leaders, telling them that they shared “a common hatred of injustice.” In public, he called apartheid “the ultimate abomination” and “the cruelest inhumanity.” Having ascended to the post of prime minister, he assured the president of Cameroon that “a Jew who accepts apartheid ceases to be a Jew. A Jew and racism do not go together.” The military relationship he had fostered was still in force.

Giving Peres not the slightest benefit of the doubt, Polakow-Suransky doesn’t consider the remote possibility that the public comments may have been sincere; that they may have brought psychic compensation to the speaker for what he’d made himself say and do in private. Golda Meir, who fostered an ambitious program of development and military outreach to newly liberated African states in the 1960s, comes off much better. The author probably romanticizes Israel’s brief honeymoon with the first generation of African leaders when he writes that they “revered” Meir.2 But it seemed a breakout by Israel from isolation and Arab embargoes at the time. When, one by one, the new states shut down Israeli programs they’d previously embraced and broke off ties, the sense of betrayal in Jerusalem made turning on the rebound to Pretoria that much easier. Finally, even Golda Meir bowed to the prevailing view that there was no choice.

Few such qualms were expressed after Menachem Begin led the Likud Party to power in 1977. Many in the party and the Revisionist Zionist movement that gave rise to it were not pretending when they expressed sympathy with the essential values of Afrikaner nationalism: the idea that a people’s claim to a land could be divinely or historically ordained, that “survival” was not something to be put to a vote of all its inhabitants. The analogy between the two situations could be carried too far but there were those on both sides who were willing to do so. Rafael Eitan, a hard-line former chief of the Israel Defense Force, told a student audience in Tel Aviv that blacks in South Africa “want to gain control over the white minority just like Arabs here want to gain control over us. And we, too, like the white minority in South Africa, must act to prevent them from taking us over.”

When finally Israel was backed into a position of support for international sanctions against South Africa, a body called the Jewish Board of Deputies, the official mouthpiece of the Jewish community there, decried the waning of “the special relationship.” Polakow-Suransky tells the story of that support for the regime as well as the story of Jews, South African and Israeli (including Israelis of South African origin), who were stalwarts against apartheid from the start. One of these, he relates, lavished praise on Nelson Mandela not long after his release from prison, before the majority-rule election that would sweep him into office as president. The former prisoner, this Israeli gushed, was a latter-day Moses who would reach the Promised Land. The normally mellow Mandela replied sharply. “The people of South Africa,” he’s quoted as saying, “will never forget the support of the state of Israel to the apartheid regime.”

That regime sunk from view sixteen years ago. The alliance that dared not speak its name had faded out by then; the warheads had been dismantled; the question of what sort of collaboration went into their production lost its urgency. All water under the bridge, we’re inclined to think, until we’re told that Washington and Jerusalem now have an “understanding” touching on issues of nuclear nonproliferation. Is it clearer now, we may wonder, than it was then? The answer is not apparent, not just in sensitive discussions the United States may occasionally have with Israel on such matters but also with Pakistan and India, not to mention North Korea and Iran. When it comes to ultimate weapons, it seems, there is always a thick shroud of murk.

This Issue

October 28, 2010

-

1

According to an article in the current (September–October) issue of Foreign Affairs by Avner Cohen and Marvin Miller, the United States promised to “tolerate and shield Israel’s nuclear program” in exchange for Israel’s pledge to avoid public disclosure of its existence and testing.

↩ -

2

I’ve another quibble that may seem parochial: the columnist C.L. Sulzberger never became executive editor of The New York Times.

↩