Philosophers interest themselves in ontological questions—questions about what kind of being something has. What kind of being do mental states have? Are they material or immaterial? What kind of being do numbers have? Are they objective abstract entities or ideas in the mind or marks on paper? What kind of being do atoms have? Are they tiny packets of matter (whatever that is) or just useful ways of summing up our observations?

In his stimulating and vigorous new book, John Searle inquires into the mode of existence of human institutions into what he calls “social ontology.”1 Money, marriage, private property, universities, presidents, citizens, banks, and corporations: What is their distinctive mode of being, and what gives rise to them? Are they, specifically, objective entities that do not depend for their existence on human minds, or are they subjectively defined entities, products of human psychology? What is an institution exactly—what is the nature of institutions as such? Searle takes answering this question to require logical analysis: he seeks the logically necessary and sufficient conditions for a given institution to exist. Thus social ontology calls for conceptual investigation—the discovery of the essence of institutions by elucidating what we mean when we speak of institutions. And an important aim of such analysis, for Searle, is demonstrating that social facts depend for their nature and existence upon what we already know of the psychological, biological, and physical world. How is it that, say, banks can exist in a world consisting solely of individual material human organisms (and other material things) with a certain type of psychology? How, in particular, do banks dovetail with brains?

Searle’s guiding principle is that social ontology depends upon psychological ontology; in other words, minds create institutions. There would be no money or marriage or private property without human minds to create these institutions. This view may strike you as something of a truism—for how else but by human decision could institutions come to be? But the question Searle seeks to address is precisely how minds create institutions: By exactly what mental mechanism do we conjure marriage and money into existence? The answer to this question can be expected to have a considerable bearing on what the social sciences are ultimately about—what they are the sciences of. Sociology, political science, economics, and anthropology all deal with social institutions, and it would be useful for them to have an analysis of what their subject matter consists in at the deepest level. Then they would know better what it is that they are studying—what the basic structure of a social fact is.

To resolve that question, Searle employs four central concepts: collective intentionality, status function, deontic power, and desire-independent reason. Collective intentionality is the capacity of a group of people cooperatively to engage in forms of intentional action, as when a club decides to admit a new category of members. What Searle calls collective recognition is of particular importance in the present case, because he will maintain that institutions depend upon a general acceptance of certain rules and rights: for example, we all agree to count certain bits of paper as having exchange value.

Status function arises from the fact that “humans have the capacity to impose functions on objects and people where the objects and the people cannot perform the functions solely in virtue of their physical structure.” A dollar bill has the status function of being usable to purchase things, not by its nature as a piece of paper, but by the fact that people collectively assign a certain status to it: it counts as money because we have jointly decided that it should so count, not because it is intrinsically worth anything. (The hundred-dollar bill is worth no more as a piece of paper than the one-dollar bill.) Status functions are thus created by collective intentionality, which is to say by a certain psychological process; they are imposed on things, by collective will.

Deontic powers are the rights, duties, obligations, and entitlements that follow from having a particular status function: thus, having money in my wallet gives me the right to engage in economic transactions, and other people have the obligation to accept the currency I offer them. Being president of the United States carries with it certain rights and responsibilities on the part of the holder, and other people have corresponding duties and obligations with respect to the president.

In general, if something or someone has a certain collectively recognized status, then various “oughts” attach—status functions entail deontic powers. Reasons independent of one’s particular desires are reasons generated by deontic powers as such: if an entity has a range of deontic powers, then we have reasons to respect those powers, even if we don’t feel like it. Often such powers are enshrined in laws that we must obey whether we want to or not. A shopkeeper may not desire to accept a particular customer’s money, but he is under a legal obligation to do so, and so has a reason to accept it whether he wishes to or not. In other words, obligations can arise merely from collectively imposed status functions—so they can arise ultimately from human decisions.

Advertisement

With these concepts in place, Searle can now proceed to his main claim: institutions arise from the collective acceptance of status functions on the part of objects and people that cannot discharge those functions independently of such acceptance. In other words, it is because we treat things as money that they are money; it is because we recognize marriage that there is marriage; it is because we respect someone as president that he is president. To put it differently, the facts exist because the corresponding concepts do; the facts follow from the application of the concepts. There can be no money or marriage without the collective employment of the concepts of money or marriage.

This makes institutional facts quite different ontologically from physical, biological, or psychological facts—which can exist independently of the corresponding concepts. A galaxy is a cluster of stars (and hence a piece of “social” astronomical real estate), but there can be galaxies in the universe without there being minds that apply the concept galaxy; galaxies do not arise from human decisions involving the concept of a galaxy. Nor do ants exist because people assign the status of ants to certain little creatures; there were ants before humans had any concepts, let alone the concept ant. Likewise for psychological facts themselves: people can have beliefs and desires, feelings and sensations, quite independently of the concepts of these things. If I am in pain now, this is not because others have chosen to assign that status to me. All these things have objective ontology; but institutions have subjective ontology—in that they depend for their being on an intentional assignment of status by human agents. Institutions fundamentally exist by human stipulation—unlike mountains, trees, toes, and quarks.

Not content with this claim of mind dependence, Searle makes a stronger claim—that institutions are language dependent. He insists, that is, that status functions are necessarily created by linguistic acts. Rightly calling this “a very strong theoretical claim,” he writes: “All institutional facts, and therefore all status functions, are created by speech acts of a type that in 1975 I baptized as ‘Declarations.'” A Declaration is a speech act that “change[s] the world by declaring that a state of affairs exists and thus bringing that state of affairs into existence.”

The central cases of these speech acts are what J.L. Austin called “performative utterances,” which are speech acts that make something the case by saying it is the case—as in saying “I promise I’ll pay you back” (by saying this you thereby promise). Thus, for Searle, the institutional fact can only exist by virtue of someone saying that it does: “Institutional facts are without exception constituted by language,” he tells us; and again: “All institutional facts are linguistically created and linguistically constituted and maintained.” There cannot—logically cannot—be banks without a linguistic declaration to the effect that such and such is a bank; no one can be married unless they have been verbally declared to be; no one can be our leader unless we have said as much.

It is important to see that this goes well beyond Searle’s initial (and plausible) claim that social ontology is grounded in psychology—that institutions depend for their being on thoughts.2 For now we are being told that thinking it isn’t enough—the thoughts must be expressed in language. Institutions depend not just on the collective recognition of status functions but also on a specific type of speech act. This means that no group of people could participate in social institutions unless they had language. It is, for Searle, logically impossible that we could come across a society of intelligent aliens that had marriage and banks and private property but were incapable of speech acts of any kind. No matter what the sophistication of their thoughts—even to the point of grasping advanced science, including psychology—they could not engage in institutional behavior, according to Searle, if they lacked language. Status functions must be assigned in speech (“This is worth one dollar!”), not simply in intention and thought.

I find this claim about speech hard to accept. I certainly don’t think Searle provides a convincing defense of it, or indeed much defense at all (beyond bald assertion). And on the face of it there seems little difficulty in the idea that collective recognition of status functions by itself is sufficient to create institutional facts: if we all regard certain things as money and use them that way, isn’t that enough to make those things money, without our having to say it out loud (or by sign language or some such)? To be sure, we can’t have marriage without the concept of marriage; but once we have the concept and collectively ascribe it to pairs of people, don’t we have all we need for the institution of marriage to exist—what need for uttering the word?

Advertisement

Of course, we humans, as we are, do possess language and make declarations that assign status functions; but the philosophical question is whether this is logically required for status functions to exist. And it looks as if it is sufficient for their existence simply that people make the appropriate status assignments in their thoughts.3 Clearly, the mere utterance of the requisite sounds will not confer status functions without the backing of thought (think of a mindless machine that merely makes the sounds “This is money”). But then why are not such thoughts sufficient by themselves to confer the desired status on things? What if we were just collectively born with the thoughts in question, but lacked the power of language—couldn’t we still create social institutions?

Someone might reply that it is not possible to have the kinds of concepts at issue here without the corresponding words. But first, we would need to see an argument for this, and Searle does not supply one (nor is he in general sympathetic to the view that thought requires language, as a general thesis). And second, the resulting position would not be Searle’s, because he thinks that language is directly involved in the production of social reality, not merely as a side effect of the (undisputed) role that concepts play. His argument is not that thought produces institutions, and thought requires language, so language is necessary for institutions. His argument is that speech acts themselves underlie the existence of social facts, not merely as a byproduct of thought. His claim, in short, is that social facts are created, constituted, and maintained by acts of speech—speech is of their very essence.

There are signs in Searle’s text that he is aware that his admittedly strong claim is rather implausible, so at certain points he appears to weaken it. Speaking of the creation of property rights, he imagines himself giving beers to three people in a pub, saying to each person “This one is yours,” thereby creating deontic powers (the exclusive right to the drink so presented). Then he remarks: “Indeed I need not say anything. Just pushing the beer in the direction of their new owners can be a speech act.” He is surely right that he can confer ownership with just such an act, but it is stretching a point to call it a speech act—what act is not a speech act, if this is one? Is sitting in a chair in the pub also a speech act because it can confer temporary rights of chair ownership on me?

Isn’t the truth here simply that the drink recipients use Searle’s act of pushing to infer that he has a certain intention about who is to have what? But they can do this without taking his behavior to be an act of speech—just as they can infer that he intends them to drink the beers by his action without their assuming that it is somehow the assertion that they should drink the beers in question. Similarly, we can use each other’s behavior to infer collective intentionality—the agreed backbone of institutional reality—without that behavior being regarded as necessarily linguistic. In other words, no verbal declaration is required in order for collective intentionality to do its institution-creating work.

Elsewhere Searle notes that not all institutions are created by explicit declarations, “because sometimes we just linguistically treat or describe, or refer to, or talk about, or even think about an object in a way that creates a reality by representing that reality as created” (my italics). He later writes: “You do not always need actual words of existing languages, but you need some sorts of symbolic representation for the institutional fact to exist.” If those symbolic representations are to include simply concepts (i.e., mental representations), then Searle is here backing off from his initial strong claim, since now unverbalized thoughts will be enough to generate social realities.

In another moment of qualification, discussing the recognition of obligations, Searle notes (trivially) that such recognition requires possession of the concept of obligation, but then he adds: “You need not have the actual word ‘obligation’ or some synonym, but you must have a conceptual apparatus rich enough to represent deontology.” Again, he and I can both agree that institutions require the backing of suitable concepts, so that they cannot exist independently of our possessing such concepts (unlike galaxies, say), but it does not follow—and is a much stronger claim—that language is of the essence. Marriage exists only because people can think about marriage (they have the appropriate “conceptual apparatus”), but this by no means entails that marriage exists in virtue of linguistic declarations.

Here Searle seems to be sliding and hedging: he wants to maintain the interesting strong thesis linking institutions inextricably to language, but his good sense tells him that the weaker thesis (quite a bit less striking) is the one that stands up to scrutiny. Thoughts and intentions are indeed the ontological basis of institutions like marriage and money; but language is a dispensable, contingent faculty when it comes to constituting the social world. The commonsense intuition that we could, however inconveniently, own private property, be married, and belong to clubs, whether or not we had the power of speech, thus emerges intact. Language may be sufficient for such institutions to exist (after all, it presupposes thought and intention), but there is no good reason to suppose that language is logically necessary.

Searle’s book is entitled Making the Social World: The Structure of Human Civilization, and this may provoke an objection I have not yet considered. I have agreed with Searle that typical human institutions depend for their existence on the possession of quite sophisticated concepts, but what about those animal species that are aptly described as social? What about herds, hives, colonies, packs, and families? Don’t elephants, bees, ants, wolves, apes, and lions (among many other species) exist in social groupings, with hierarchies and division of labor and cooperation? And yet presumably these social structures are possible without the animals in question having the concepts of herd, hive, etc.—let alone words for these things. So isn’t it simply false to say that the “social world” is defined by means of collective intentionality, status functions, and deontic powers (not to mention declarations)?

I wish Searle had carefully considered this question (beyond a perfunctory mention). At the very least his title is quite misleading. His reply to the objection would presumably be that he is considering the specific form that human social reality takes, which is far more sophisticated than that of other “social” animals. Fair enough, but then the scope of his theory is actually quite different from what his title suggests; and actually it becomes murky quite what the scope of the theory is intended to be. Humans, of course, can cohabit and exist in families and even belong to tribes and form hunting parties without the kind of conceptual backing Searle’s theory posits; but he is excluding these by stipulation from his purview, even though they are clearly social configurations in any normal sense.

What he appears to be considering are social arrangements that have a kind of legal backing—hence the emphasis on rights and obligations. Most of his examples of institutions belong to this class of legally sanctioned social phenomena—money, marriage, private property, and presidents. But it is far from clear that the social and the legal (even under a broad interpretation) coincide in any sense that is not merely stipulative. His interest appears to be in cases in which there are rules that carry penalties for violation, but these are not coextensive with the intuitive notion of the social. He relies on our antecedent grasp of the notion of the social to get his inquiry off the ground, but it turns out that he has something far more limited in mind—which I do not think he ever manages to identify clearly (he usually just sticks to lists).

The same can be said about the subtitle. He is actually not discussing “civilization” in the ordinary sense, and so he is not providing the structure of that complex entity. By “civilization” we would normally mean to include art, science, architecture, technology, and other aspects of “culture”: but Searle offers no analysis of any of these things, and his theory obviously does not encompass the full range of so-called civilization. (Of course, there are institutions associated with art, science, and architecture, but I am talking about the things themselves—artistic works or scientific theories or buildings that have actually been created.) Nor do I suppose that he intends to cover that large territory; he means something far more specific. But then that should be made clear and his intended domain identified more precisely. The upshot is that it is never altogether clear what his book is about, though it is clear that it is not about what the title and subtitle say it is.

Searle often stresses the remarkable creative power of human intentionality—the ability of the mind to create vast and intricate social arrangements, like nation-states, financial systems, and universities. In a certain sense, he tells us, we conjure these things out of thin air—just by declaring them to be so. One of his paradigms is the creation ab initio of limited liability corporations just by legal fiat. No doubt he is right that this is a remarkable and destiny-changing power, not possessed by other animals; but I think that in his zeal to press the point he exaggerates it in a way that could stand correction. It is his fixation on the performative that leads him astray here: it is true that I can promise just by declaring that I promise, thus conjuring a promise from thin air (there wasn’t a promise lurking there before that I am merely reporting). But I don’t think we typically create social realities in this magical-seeming way, linguistically pulling the institutional rabbit from the hitherto empty hat. We always need a prior foundation of preinstitutional reality in order to get institutions off the ground. Universities typically arise from prior informal teaching, as with Socrates and Plato’s Academy.

The people and objects on which we confer status functions must always be suitable to serve the function in question; not just anything will do. Consider artifacts—chairs, computers, and cars. It is plausible that physical things fall under these concepts because of the way humans regard and use the entities in question; nothing is a chair, say, just in virtue of its physical properties—an object must be designated a chair to be a chair. I may sit comfortably on a rock or a log but I wouldn’t call either one a chair. It should, moreover, be at least as obvious that mere designation will not suffice to make something a chair—I could not designate a fly or a puddle as a chair. The object that counts as a chair must be physically suitable to be so designated. Thus the ontology of chairs is a mixture of the human assignment of function and having the right physical structure.

In the same way, I suggest, something can count as money only if it is suitable to function as money in virtue of its physical attributes; mere stipulation alone won’t cut it. For a type of entity to work as money it needs to be portable, exchangeable, relatively stable, detectable, etc. You couldn’t just stipulate that regions of space will be money or electrons or stars. Nor could you successfully stipulate that two rocks are now married. We can’t just graft institutional reality onto anything or nothing; we have to respect the constraints that concrete reality offers. If so, institutions, like artifacts, are a combination of human intention and antecedent physical reality, not merely products of the former. Social ontology therefore combines mind-independent facts with Searlean mind-dependence; the ontology is bipartite and composite. It mixes the natural and the intentional. The mode of being of the social has a hybrid character.

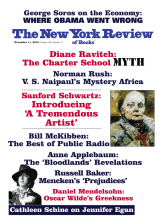

This Issue

November 11, 2010

-

1

Searle has an earlier book on the same subject, The Construction of Social Reality (Free Press, 1995), which covers many of the themes of the book under review. I reviewed this book in The New Republic (May 22, 1995); the review is reprinted in my Minds and Bodies: Philosophers and Their Ideas (Oxford University Press, 1997).

↩ -

2

In his earlier book Searle adopted essentially this position. I think he should have stuck with it. It should be noted that his new position, in which language is declared essential, has nothing to do with the need to communicate our thoughts and intentions to each other, still less with the idea that things like marriage depend on public ceremonies with a verbal component.

↩ -

3

It is a question whether all thought, in humans and others, is conducted in language—as when I silently say something to myself. But we don’t need to take a stand on that question here: the essential point is that no overt speech act needs to be performed in order to have a particular thought—no Declaration in Searle’s sense. Nor does Searle ever argue that language is necessary to institutions because all thinking occurs in language; he takes the necessary speech act to be something in addition to interior thought—and that is what I am questioning.

↩