In the first decades of the twentieth century, a committed modernist had two ambitions: to make something new and to recover something old. In the search for new forms for the new age, it seemed as though everything was inspirational, and that the entirety of human history was rushing into the present: the folk songs and folk tales of European peasants, African and Inuit masks, Japanese haiku, Celtic rituals, Navajo blankets, Etruscan funerary sculpture, the unreconstructed fragments of classical Greek poetry, Oceanic shields and tapa cloths, alchemical drawings… The way into the future and out of the recent past—the perceived straitjacket of nineteenth-century art and mores—was to go back to the distant past.1

China, as the oldest continuing civilization, was inevitably magnetic. Paul Claudel was the French vice-consul in Shanghai and Fuzhou, and modernist Sinophilia begins exactly in 1900 with his perhaps overly Catholic book of prose poetry, Connaissance de l’est (Knowledge of the East). He was followed by Victor Segalen, who went to China as a medical officer, produced a scholarly history of the stone statuary, and wrote two of the greatest books of chinoiserie: Stèles—prose-poem “translations” of nonexistent originals, based on stone inscription tablets, and published as a Chinese-style book in Beijing in 1912—and the uncharacterizable novel René Leys, set in the Forbidden City during the Boxer Rebellion, which appeared posthumously in 1922. Two years later, Saint-John Perse, who had served as secretary in the French embassy in Beijing, published Anabasis, a series of prose poems set in an imaginary Central Asia. Although somewhat forgotten now, it was, along with The Waste Land, the most internationally influential book of poetry of its time, and was translated by T.S. Eliot, Walter Benjamin, and Giuseppe Ungaretti. Anabasis in turn led to Henri Michaux’s 1933 A Barbarian in Asia (which was translated by Borges) and Michaux’s lifelong experiments in a calligraphy attached to no language.

Nearly everywhere, ancient China was inextricable from the early avant-garde. The Mexican poet José Juan Tablada introduced Apollinaire’s calligraphy-inspired concrete poems (calligrammes) into Spanish in 1920 with a book called Li Po and Other Poems; one of the poems is in the shape of the character for “longevity,” a Taoist charm. The first major book in English of the new, imagistic free verse was Ezra Pound’s translations of largely Tang Dynasty poems, Cathay. Published in 1915, its poems from a thousand years earlier of soldiers, ruined cities, abandoned wives and friends had an immediacy for those in the trenches and those waiting at home. And Pound discovered (or, more exactly, semi-invented) in the structure of the Chinese ideogram itself a model for bringing disparate elements together into a single dynamic object of art. Sergei Eisenstein, studying Chinese, independently discovered the same thing, which he turned into his theory of film montage.

The modern German novel begins in 1915 with Alfred Döblin’s The Three Leaps of Wang Lun. More a curious artifact than a great book—though Günter Grass has said that his own prose is “inconceivable” without it—Wang Lun was an amazingly well-researched historical novel, set in the eighteenth century, but written in the expressionistic style that Döblin perfected years later in Berlin Alexanderplatz. Bertolt Brecht loved the book, and it was perhaps the germ of his Sinophilia, which led to his translations of Arthur Waley’s translations of Chinese poems; an adaptation of Li Xingdao’s thirteenth-century play The Chalk Circle, relocated to the Caucasus; and The Good Person of Sichuan. (Brecht, in turn, was the first contemporary Western dramatist to have his work presented in China.) At his death he left an unfinished play, The Life of Confucius, that was to be performed entirely by children.

It is probable that Brecht read Béla Balázs’s 1922 contribution to German chinoiserie, The Cloak of Dreams. What is certain is that they knew each other in the various theatrical and political circles in Berlin, and not happily: Brecht sued the director G.W. Pabst after he was fired—and Balázs hired—as the screenwriter for the film version of Brecht’s own Threepenny Opera.

Except among a few film and music scholars, Balázs is barely remembered, and only four books from the mountain of his works—novels, stories, poetry, plays, puppet plays, screenplays, libretti, political articles, and film criticism—have ever been translated into English.2 But he was an archetypal modernist, a type that is now nearly extinct: the man who seemed to know everyone, do everything, and write everything.

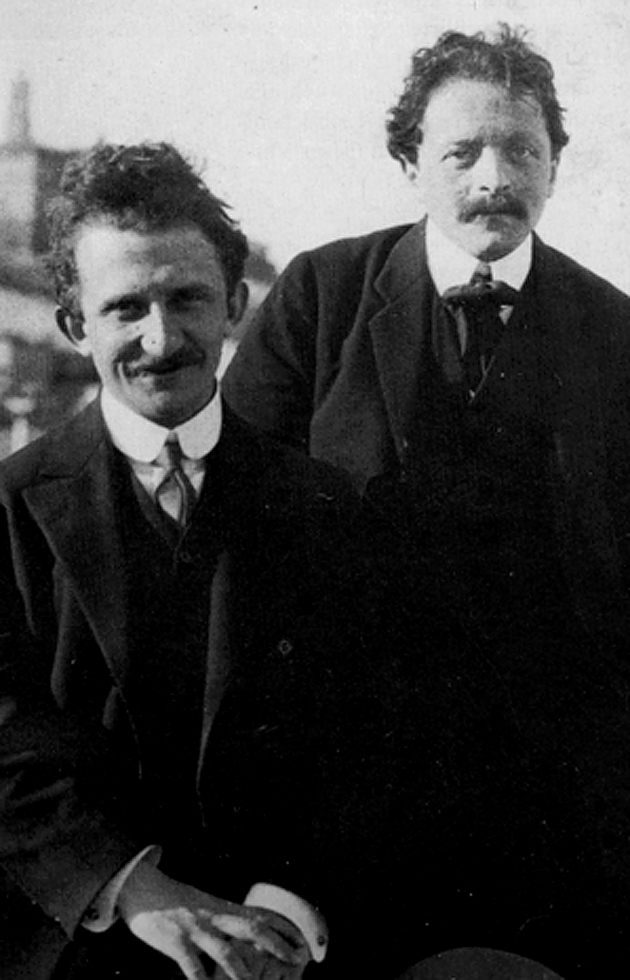

Born Herbert Bauer in Szeged, Hungary, in 1884, he took the pseudonym Béla Balázs for the poems he was contributing to the local newspaper while still a schoolboy. At the university in Budapest, his roommate was Zoltán Kodály and his friends were Béla Bartók and György Lukács. With the two composers, he used to tour the countryside, collecting folk songs and fairy tales. After studies with Georg Simmel in Berlin and Henri Bergson in Paris, he returned to Budapest, where, among many other things, he wrote the libretto for Bartók’s 1911 opera Duke Bluebeard’s Castle and the story for his 1917 ballet The Wooden Prince—perhaps the only Balázs works that are still widely known.

Advertisement

A volunteer soldier in World War I, he became seriously ill and was luckily discharged early. He spent the rest of the war in Budapest as an antiwar polemicist and a participant in Lukács’s Sunday Circle of radical intellectuals. An active supporter of the revolution that very briefly brought communism to Hungary in 1919, he was in charge of literary affairs for the new government, promoting theater and films and creating a department of folk tales. After the regime was overthrown by the neighboring Romanians and Czechs, Balázs, who had fought with the Red Army, escaped into exile in Vienna. Friends with Robert Musil and Arthur Schnitzler, among other Viennese writers, he was also part of a crowd of Hungarian film exiles, including Sándor Kellner (who became Sir Alexander Korda), Mihály Kertész (who became Michael Curtiz), and Béla Lugosi (whose exotic roles no doubt allowed him to keep his name in Hollywood). He became the world’s first film critic of note, inventing the idea of the daily film review for the newspaper Der Tag.

His first book of film theory, The Visible Man (1924), was translated into eleven languages and was enormously influential among young directors, particularly in Germany and the Soviet Union, with its evocation of film’s ability to speak a universal language of the body and its celebration of techniques previously impossible in the theatrical arts: the close-up and the point of view. “I do not watch Romeo and Juliet from the pit,” he later wrote,

I look up to the balcony with Romeo’s eyes and down at Romeo with Juliet’s eyes…. I look at the world from their point of view and have none of my own…. Nothing like this kind of identification…has ever occurred in any other art.

The distance between spectator and spectacle had been erased, much like the Chinese story he cites—also one of Walter Benjamin’s favorites—of the painter who walks into his own painting.

In 1924, when radio broadcasts were just beginning—the one in Austria was less than a year old—Balázs imagined the birth of a new art form, the radio play, a theater strictly for the ears, as the silent cinema was strictly for the eyes. But much like critics of the Internet today, he warned that, with the whole world immediately accessible, radio would lead to a global homogenization of culture. Worse, radio would become a chaos of disembodied voices spreading both truths and falsehoods, where “the Communist can pose as a Fascist and the Fascist as a Communist,” where “everyone can hear everything and no one knows what to believe.”

He moved to Berlin in 1926, wrote and directed plays for Marxist theater collectives, collaborated with Erwin Piscator on agit-prop, and wrote a libretto for Ernst Krenek, novels, stories, and hundreds of articles for newspapers and left-wing journals. He was a hot screenwriter, working with Pabst on The Threepenny Opera, Eisenstein on The General Line, and films by Kurt Bernhardt (who became Curtis Bernhardt) and Hermann Kosterlitz (who became Henry Koster). His box-office smash, Korda’s Madame Wants No Children, was an unlikely pro-abortion comedy, and featured a walk-on by the beautiful Marie Magdalene von Losch (who became Marlene Dietrich). A guru to the young Billy Wilder, his ideas would resurface in Walter Benjamin (who found him irritating in person, mystical and banal), Rudolf Arnheim, and Siegfried Kracauer. In 1930, his second book of film theory, The Spirit of the Film, was almost unique among cinephiles in welcoming the advent of talking pictures, and it presciently argued for the immediate establishment of film archives.

A popular German actress, Leni Riefenstahl, asked him to write the script for her first directorial effort, The Blue Light, an ethereal tale of a light in the mountains that appears with the full moon, luring young men to their deaths, and the beautiful young peasant woman who knows its secret source in a cave of blue crystals. Balázs was close to Riefenstahl on the set, and reportedly directed the scenes in which she appeared. He invited her to go with him to Moscow, where he had been hired to write a screenplay, but she had to stay and edit the film. By the time he returned, she had been born again after a reading of Mein Kampf. She took his name off the credits of the film, refused to pay him, and referred to him, in a letter to Julius Streicher, publisher of the anti-Semitic newspaper Der Stürmer, as “the Jew Bela Balacs [sic].”

Advertisement

In 1933, National Socialism drove him permanently to the Soviet Union, where he taught and wrote plays, poems, and screenplays for the next, extremely difficult, fourteen years. Although he was under continual attack for offenses like “subjective idealism,” he managed, unlike many of the Hungarian Communists, to avoid execution or the gulag. How he managed remains unclear, and may have been pure chance. Much of the time he was living in the forest in a dacha far from Moscow, and there is speculation that he was simply forgotten. During the war, he was in Kazakhstan, having unwisely turned down an offer to join the European exiles teaching at the New School in New York.

In 1947, he was sent back to the now Soviet-controlled Hungary, publishing a third book of film criticism, Theory of the Film, writing poems, novels, plays, articles, and collaborating on two films that had success abroad: Géza von Radványi’s Somewhere in Europe (praised by André Bazin as a masterpiece of neorealism) and István Stöts’s Song of the Cornfields.

Well known in foreign film circles, he was inevitably denounced for “agitative secularism” and the like by the Party orthodoxy at home—including his old friend Lukács, whom he had helped to release from the Lubyanka prison during the war. He died in 1949, on the verge of moving to East Berlin as an adviser to the GDR film industry. Almost needless to say, he was posthumously honored by those who had attacked him, and the Béla Balázs Studio was founded in Budapest in 1959 to encourage young filmmakers.

Balázs wrote fairy tales his entire life, but The Cloak of Dreams was an unusual commissioned project. In 1921, the illustrator Mariette Lydis created a series of aquarelles on “Chinese” themes, in the style of a simplified Aubrey Beardsley, with some touches of German Expressionism. She then asked Balázs, in effect, to embody her illustrations by writing accompanying texts. He had three weeks to complete the project, as the publisher was eager to have it available for Christmas.3

It is a tribute to Balázs’s skills as a storyteller that he was able so quickly to spin elaborate tales out of single, simple scenes. The image of an obese mother suckling a baby turns into the story of a man who is thousands of years old because, for complicated reasons, he had to keep repeating his infancy. An equally obese couple sleeping becomes the story of a man who is reborn as a flea; he conspires with a talking silver fox to bring his future parents together so that he’ll be reborn as a human. A straightforward portrait of a parasol vendor leads Balázs to imagine an unhappily married street peddler who finally finds peace at home after buying a series of magic parasols, each one of which produces a different kind of weather.

Despite the usual trappings of opium, jade, rice paper, bamboo, and tea, the stories, as might be expected, are not particularly Chinese. Most of them could easily have taken place in another exotic empire, Persia or India. They are much more in the tradition of the German Romantic Kunstmärchen, the literary fairy tales of the brothers Grimm or E.T.A. Hoffmann, or the contemporary Orientalist fairy tales that were being written by Hermann Hesse and Thomas Mann, than the Chinese rough equivalent, the “strange stories,” best known in the West in Pu Songling’s seventeenth-century Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio.

The Chinese stories are more deadpan and satirical and, moreover, are meant to be reports of true events. A typical story is the man obsessed with peonies who forsakes his family and goes into debt when, in the middle of winter, he starts waiting for the peonies to blossom. Or the collector of rare breeds of pigeons who ceremoniously presents his best pair of specimens to a high-ranking official, who later tells him that they were indeed tasty, but not particularly different from ordinary pigeons. The stories are full of ghosts and demons. A man will marry a beautiful maiden, living happily with her until the day he discovers a demon with a pile of human skin next to him, carefully applying makeup to it. Then he must decide whether to keep on living in bliss with a monster.

The translator Jack Zipes, in an informative but long introduction—it takes up a third of the book—claims that Balázs’s tales were heavily influenced by Taoism, but this seems somewhat far-fetched and ignores the more likely Theosophism to which he was attracted. Despite the presence of an utterly idiosyncratic Laozi (Lao Tzu in the older transcription) in one of the stories, Freud more often appears to be the resident sage. The skulls of a man’s father, grandfather, and great-grandfather torment and eventually devour him. In the title story, the wife of the emperor weaves scenes from her dreams into her husband’s cloak. She only desires him when he is wearing it; when he takes it off, her desire vanishes.

In the final story, a warrior must fight to win the hand of one of three princesses. He chops off the arm of the first suitor, but the eldest daughter takes pity and marries the wounded man; he chops off the leg of the second, but the middle daughter also takes pity and does the same; so he chops off the head of the third. The youngest daughter says that the poor man should not die without a widow to mourn him; the warrior, in a shockingly abrupt ending to the book, goes home and kills himself. And there are three stories of friendship that are said to reflect Balázs’s contentious relationship with Lukács: feuding neighbors are reborn as Siamese twins; two inseparable friends turn into each other in a permanent opium dream; and—illustrating a grotesque picture of a fat man caning the naked buttocks of another—a man must beat his friend almost to death in order to save him.

The most Chinese (and simultaneously most modern) of Balázs’s stories is one that was not part of the original collection, but is included here as an appendix: “The Book of Wan Hu-Chen.” A penniless man is in love with the governor’s daughter. She rebuffs him, so he decides to write a book about her, making her even more beautiful and elegant than she is in life. Eventually she comes out of the book to visit him, but Wan has made, out of modesty, a terrible authorial mistake. In the book she is in love with the dashing Prince Wang. Wan then has to write a chapter killing off Prince Wang. The maiden turns to Wan for solace and they live on happily for many years—he, writing the book all day, giving her ever finer jewels and clothes; she, coming out of the book at night. But he grows older and poorer, having no other occupation, and she remains young and beautiful. They have a son who remains in the real world and is the reincarnation of Prince Wang. Wan, penniless, finally gives the boy to the governor’s family and discovers that the real daughter had died the day he began writing; he goes off into the pages of his own book to live in eternal springtime with his true love.

A somewhat similar Chinese “strange story” is more disturbing. A young man spends all of his time reading, but he’s not very bright and cannot understand what he reads. He reads indiscriminately, day and night, in the enormous library he has inherited, never knowing the difference between a good book and a bad, a friendless, ridiculous figure who cannot pass his exams. He develops a longing for a woman he comes across in the pages of the History of the Han Dynasty. She, too, eventually comes out of the book to teach him, at age thirty-three, all the joys of life that eluded him while he was reading. He has never known such ecstasy. But then a local magistrate, hearing rumors of a demon in the house, burns down the library. Devastated, the bookworm’s obsession turns into a dedication to revenge. He quickly passes his exams, becomes the governor, and ultimately destroys his enemy, though he has, of course, forever lost the maiden.

The fairy tale, in the first decades of the twentieth century, served various contradictory purposes. It was the voice of the people, uncorrupted by bourgeois values; or it was the expression of a national spirit, of a folk unpolluted by foreign influence; or it was the manifestation of universal psychological states, the tropes of a collective unconscious.

For Balázs, the good modernist, what was thrilling was the connection between films and fairy tales, what was newest and what was most archaic. The previously unseen worlds presented in nature films was like fairyland; so was the entirely self-contained universe of cartoons; Charlie Chaplin was like the fairy tale of the ignorant farmer who thought he could carry sunlight into a windowless church in his sack. “For the urban population of today,” he wrote in 1922, “the cinema is what folk songs and folktales used to be.” Robert Musil said that reading Balázs on film was like reading the anthropologist Lucien Lévy-Bruhl on magical thinking.

Unlike others, he did not believe that the movies would mean the end of stories and novels, and it is not surprising that he wrote The Cloak of Dreams at the same time that he wrote his first screenplay. In the present moment, when fiction has yet again been declared dead, these deliberately anachronistic, pseudo-Oriental, and completely delightful tales are further examples of the perennial human need for imaginative narrative told in words.

This Issue

November 25, 2010

-

1

In the prevailing evolutionary narrative of culture, contemporary tribal artifacts were seen as relics from the past, the “childhood of man.” ↩

-

2

Theory of the Film was published in the UK in 1952 and is available online at www.archive.org. Early Film Theory: Visible Man and The Spirit of Film very recently appeared in an expensive academic edition from Berghahn Books. ↩

-

3

This is the second English translation of the book. The first, by George Leitmann, was published in a pretty edition by Kodansha in 1974, under the title The Mantle of Dreams. There are no apparent significant differences between the two versions, and Leitmann’s, apart from the archaicizing use of “thou,” reads slightly better. ↩