In response to:

Shylock in Red? from the October 14, 2010 issue

To the Editors:

Stephen Greenblatt tries to justify his claim that Shylock was originally played with a red beard and a hooked nose by citing as evidence a ballad published by Thomas Jordan some seventy years after Shakespeare’s play was first performed [“Shylock in Red?,” Letters, NYR, October 14]. The ballad, Greenblatt writes, not only “retell[s] the plot of Shakespeare’s play” but also “provides a highly probable glimpse” of its early staging. Does that glimpse extend to Jordan’s other recollections, if that is what they are? Among my favorites (and I have to supply the familiar Shakespearean names since Jordan doesn’t use them): that it is a disguised Jessica and not Portia who defeats Shylock in the courtroom scene—and who then marries Antonio! We’re left with a fundamental disagreement about what constitutes historical evidence for interpreting Shakespeare’s life and works.

James Shapiro

Columbia University

New York City

Stephen Greenblatt replies:

In a previous letter, James Shapiro claimed that my remark that in early productions of The Merchant of Venice Shylock’s appearance was, as I put it, that of “the wicked Jew of anti-Semitic fantasy” was based on a nineteenth-century forgery. In reply, I cited as evidence the 1664 ballad by the actor Thomas Jordan, describing an extravagantly hook-nosed, red-bearded Shylock. I readily acknowledged that this ballad was not proof positive. There are virtually no detailed, reliable records of late-sixteenth- and early-seventeenth-century productions of any of Shakespeare’s plays, so that all discussions of the subject are inevitably and inescapably speculative.

Accounts become fuller from the eighteenth century onward. In 1775 a spectator who saw the celebrated actor Charles Macklin playing Shylock described him thus: “a rather stout man with a coarse sallow face, a nose by no means lacking in any one of the three dimensions, a long double chin; as for his mouth, Nature’s knife seems to have slipped when she carved it and slit him open on one side all the way up to the ear” (quoted in John Gross, Shylock: A Legend and Its Legacy, Simon and Schuster, 1992, pp. 113–114). In the early nineteenth century William Hazlitt summed up eloquently the kind of Shylock that he and everyone else expected to see on stage:

…a decrepit old man, bent with age and ugly with mental deformity, grinning with deadly malice, with the venom of his heart, congealed in the expression of his countenance, sullen, morose, gloomy, inflexible, brooding over one idea, that of his hatred, and fixed on one unalterable purpose, that of his revenge [Gross, p. 124].

It was this expectation of a nightmarish villain that led to the deep surprise that Hazlitt and his contemporaries felt at the nuanced and even sympathetic performance of Edmund Kean.

There is no internal evidence in the text of Shakespeare’s play that indicates how Shylock is meant to look. That he could therefore have closely resembled the Christian Antonio is, as I remarked, a potential meaning of Portia’s courtroom question: “Which is the merchant here, and which the Jew?” (The line could alternatively, of course, be meant to elicit a laugh or to suggest that before the law, all parties are equal, no matter how different they appear to be.) Shylock’s clownish servant Lancelot calls him “the very devil incarnation” (2.2.22–23), Solanio says that the devil “comes in the likeness of a Jew” (3.1.19), and Graziano calls him a “damned, inexorable dog” (4.1.127), but none of these insults need be reflected in the Jew’s physical appearance. When Shakespeare absolutely wanted one of his characters to look different from the surrounding characters—hunchback Richard, for example, or obese Falstaff—he was careful to incorporate the difference directly into his text. In The Merchant of Venice he did not do so.

That said, does James Shapiro or anyone else actually believe that there is no stage history of grotesquely stereotyped Shylocks, physically as well as spiritually repellent? Surely what matters here is that there are two strong traditions, both on the stage and on the page, in understanding and representing Shylock’s character. One sees him as a twisted, conniving monster and often depicts him accordingly. The other sees him as a psychologically complex being virtually indistinguishable (often in appearance as well as character) from the surrounding Christians of Venice.

Particular productions can draw on one tradition more than another, just as there are whole historical periods in which one has outweighed the other, but it is important to understand that both possibilities are present in the role. Any serious account of The Merchant of Venice needs to grapple with this haunting doubleness, for it has helped to make the play the remarkable thing it has been now for four centuries: a bone caught in the throat that can be neither coughed up nor comfortably swallowed.

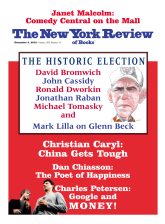

This Issue

December 9, 2010