David Garland is a well-respected sociologist and legal scholar who taught courses on crime and punishment at the University of Edinburgh before relocating to the United States over a decade ago. His recent Peculiar Institution: America’s Death Penalty in an Age of Abolition is the product of his attempt to learn “why the United States is such an outlier in the severity of its criminal sentencing.” Thus, while the book primarily concerns the death penalty, it also illuminates the broader, dramatic differences between American and Western European prison sentences.

Describing his study, Garland explains:

When I talk to people about my book on capital punishment, the first thing they inevitably ask is, “Is your book for it or against it?” The answer, I tell them, is neither.

In fact, despite its ostensible amorality, his work makes a powerful argument that will persuade many readers that the death penalty is unwise and unjustified.

His explanation of why the United States retains capital punishment is based, in part, on the greater importance of local decision-making as compared with the more centralized European governments with which he was familiar before moving to New York. Some of his eminently readable prose reminds me of Alexis de Tocqueville’s nineteenth-century narrative about his visit to America; it has the objective, thought-provoking quality of an astute observer rather than that of an interested participant in American politics.

As is typical of many Supreme Court opinions rejecting legal arguments advanced by defendants in capital cases, Garland’s prologue begins with a detailed description of a horrible crime that will persuade many readers that the defendant not only deserves the death penalty but also should be subjected to the kind of torture that was common in sixteenth-century England. Garland also describes such torture in detail. This “emotional appeal” of the death penalty, Garland declares, is an important topic in his study.

His first chapter then includes a graphic description of the 1757 execution in Paris, France, of Robert Damiens, who tried to assassinate Louis XV, and an even more graphic description of the 1893 lynching of Henry Smith in Paris, Texas. Each was a gruesome public spectacle witnessed by a large, enthusiastic crowd. Of the latter, Garland writes:

between three and four hundred spectacle lynchings of this kind took place in the South between 1890 and 1940, along with several thousand other lynchings that proceeded with less cruelty, smaller crowds, and little ceremony.

Garland uses the “archetypal Southern lynching scene,” another gruesome execution, and chilling murders to orient his study. Not until page 36 does he pose the question that had already occurred to me: Would his analysis differ if he had initially discussed Michigan’s pathbreaking 1846 decision to abolish capital punishment for crimes besides treason? In 1846, Michigan had not executed anyone for fifteen years. Its legislature regarded the death penalty as a “dead letter,” quite inessential to crime control. Shortly before, two innocent men—one in Canada and one in New York—had been executed. Unsurprisingly, the committee report stressed the “fallibility” of the punishment. Even though Wisconsin and Rhode Island soon followed Michigan’s abolition, Garland seems to discount its importance, seeing it as the work of a small group of liberal reformers with New England backgrounds that, in his view, may not have reflected most Michiganders’ views.

Had Garland made the Michigan abolition his starting point, I suspect that readers might have been inclined to disagree with the death penalty. Execution of innocents is disturbing, both to many today and, I presume, to Michigan voters then willing to endorse their leaders’ reasoned abolitionist positions. Readers will presumably have a similar reaction to his observation that exonerations, “whereby condemned individuals are found to be innocent and are released from custody,” have “become a recurring feature of the system; indeed, since 1973, more than 130 people have been exonerated and freed from death row,” a number on the basis of DNA evidence.

Garland’s argument is historical and contemporary. Chapters 2–6 situate the modern American death penalty within US and European histories of capital punishment. On both continents, capital punishment has roots in gruesome and public spectacles: unspeakable torture and postmortem desecrations of offenders’ remains designed, respectively, to maximize suffering and exalt the omnipotence of the sovereign. In Europe, the greater availability both of deportation and of prisons led to reductions in executions, and new techniques like the guillotine made executions somewhat more humane. Eventually, in the modern period, where it survives, fundamental changes in the timing and character of executions have profoundly altered its retributive and deterrent potential.

A “lengthy and elaborate legal process has become a central feature of American capital punishment.” As a result, several executions have occurred after a delay of more than twenty years,

Advertisement

and some prisoners currently have been awaiting their executions for more than three decades…. Such delays do not just undermine the death penalty’s deterrent effect; they also spoil its capacity for satisfying retribution.

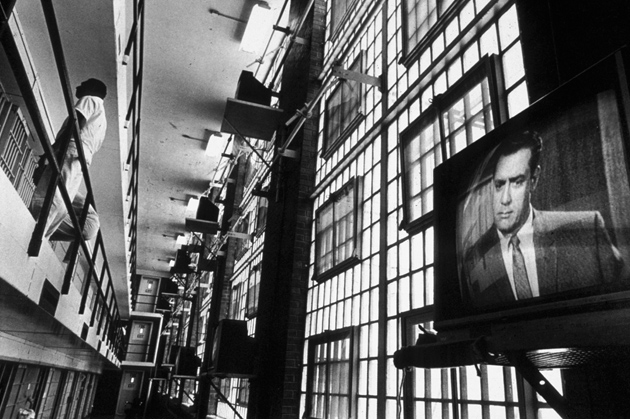

Changes designed to avoid needless infliction of pain have had the same effect. What once was a frightening public spectacle now resembles painless administration of preoperative anesthesia in the presence of few witnesses. American officials do not enjoy executions; “they seem, in short, embarrassed, as if caught in a transgression.”

Europeans abolished the death penalty in the decades after World War II. History, Garland contends, explains much of this transatlantic difference. In Europe,

the sequence of events was first, the formation, extension, and consolidation of state power; second, the emergence of bureaucratic rationalization; and third, the growth of popular participation.

In the United States, Garland argues, the sequence was reversed. As a result, criminal justice bureaucrats and national parties in Europe—once they became motivated to do so—imposed abolition despite popular opposition. In the United States, abolitionists found the more politicized bureaucracy and the relatively weak national parties inadequate to the task of overriding public support.

Having established that US death penalty policy is largely set locally, Garland turns to describing why and in what ways the United States retains capital punishment. In Chapter 7 he cites a tradition of community-level executions dating to colonial times, frontier beliefs in meeting violence with violence, and pluralism that inhibits solidarity with victims. Chapter 8 reviews the Legal Defense Fund’s litigation, which in 1972 produced, in Furman v. Georgia, a moratorium on executions in the forty-two jurisdictions that authorized them. The backlash was swift, as the following chapter shows in detail. Thirty-four states enacted new death penalty laws before the decade was out. One—Oregon—had not previously authorized capital punishment.

Attacks on Furman, like the related vigorous and continuing criticism of liberal Warren Court decisions protecting the rights of criminal defendants and minority voters, were an important part of the Republican Party’s “Southern strategy.” The history of racism in the South partly explains the appeal of the “states’ rights” arguments that helped move the “solid South” from the Democratic to the Republican column in national elections.

After Furman, Garland argues in Chapter 10, the Supreme Court focused on transforming capital punishment, requiring new procedural protections, reducing the cruelty of executions, and devolving power to “the people” at the local level. The concern with local policymaking that Garland emphasizes, however, has not prevented Supreme Court decisions from eliminating categories of defendants (juveniles and the mentally retarded) and offenses (rape and unintentional killings) from exposure to capital punishment nationwide.

For Garland, the death penalty is “a strange social fact that stands in need of explanation.” He approaches it and debates around it “with the sorts of questions and concepts that anthropologists bring to bear on the exotic cultural practices of a foreign society they are struggling to understand.” In his view, an important reason Americans retain capital punishment is their fascination with death. While neither the glamour nor the gore that used to attend public executions remains today, he observes, capital cases still generate extensive commentary about victims’ deaths and potential deaths of defendants. Great works of literature, like best-selling paperbacks, attract readers by discussing killings and revenge. Garland suggests that the popularity of the mystery story is part of the culture that keeps capital punishment alive. As he explains in Chapter 11, current discourse about death reflects how the purposes that American capital punishment serves have changed over the years.

Garland concludes that capital punishment today is “reasonably well adapted to the purposes that it serves, but deterrent crime control and retributive justice are not prominent among them.” Instead, the death penalty promotes “gratifications,” of “professional and political users, of the mass media, and of its public audience.” In particular, he contends, capital punishment derives “its emotional power, its popular interest, and its perennial appeal” from five types of “death penalty discourse.” They are: (1) political exploitation of the gap between the Furman decision and popular opinion; (2) adversarial legal proceedings featuring cultural tensions between capital punishment and liberal humanism; (3) the political association of capital punishment with larger political and cultural issues, such as civil rights, states’ rights, and crime control; (4) demands for revenge; and (5) the emotional power of imagining killing and death. He concludes that “the American death penalty has been transformed from a penal instrument that puts persons to death to a peculiar institution that puts death into discourse for political and cultural purposes.”

Notably, Garland all but denies that the death penalty serves significant deterrent purposes. Death penalty states, after all, have generally higher crime rates than “abolitionist” ones. For Garland, this differential helps—by eliminating one possibility—to explain the people’s decisions; it tells us nothing about the wisdom of those decisions.

Advertisement

To illustrate how political and cultural purposes of the death penalty have replaced penal purposes, he writes:

Support for death penalty laws allows politicians to show that they support law enforcement…. California Senator Barbara Boxer bragged that she voted 100 times for the death penalty. And George W. Bush first ran for president in a year when, as governor of Texas, he had presided over the largest number of state executions ever carried out in a single twelve-month period—a total of forty in the year 2000.

Similarly, local elections affect decisions of state prosecutors to seek the death penalty and of state judges to impose it. “In states where judges were until recently empowered to override jury sentences,” Garland explains, “elected judges typically used this power to impose death rather than life. In Alabama the death-to-life ratio of these judicial overrides was ten to one.” In Delaware, where judges are not elected, such decisions favored defendants. The “tight connection between legal decision-making and local politics produces…an obvious risk of bias in capital cases.” Popular opinion has less effect on criminal justice in Europe. European judges and prosecutors are typically tenured civil servants. Popular opinion thus has less sway over individual trials. This difference provides a powerful argument for opponents of judicial elections.

The structure of European democracies also makes it more likely that majorities will defer to deliberative decisions by national leaders and experts, a dynamic that the British decision to abolish the death penalty exemplifies. In the 1950s, the Report of the Royal Commission on Capital Punishment opposed the death penalty. Despite the fact that an opinion poll showed that 70 percent of Britons supported capital punishment for murderers of police officers, Britain abolished capital punishment in the 1960s. As time passed, more Britons embraced abolition. By 2006, less than half supported capital punishment for murderers of police officers.1

Parallel developments occurred in the United States prior to President Nixon’s election. “America in the 1960s stood on the verge of abolishing capital punishment, as did Britain, Ireland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and most of continental Europe.” The Warren Court was still “operating as an engine of liberal reform”; in 1964 Lyndon Johnson won a landslide victory; in 1965 Congress enacted the Voting Rights Act, dramatically changing electoral practices in the South; and in 1966 a Gallup poll found that most Americans opposed the death penalty. Prominent elected officials took abolitionist positions without apparent political cost.

In 1963 Justice Arthur Goldberg published a dissent from the Supreme Court’s refusal to review Rudolph v. Alabama, in which the defendant was sentenced to death for rape. Consistently with his treatment of most debates about capital punishment as having an all-or-nothing character, Garland reads that dissent as having signaled to the civil rights community that constitutional challenges to the death penalty would find judicial support. In fact, Justice Goldberg’s published opinion merely identified the narrower question of whether death is a permissible punishment for rape—a question resolved negatively in Coker v. Georgia (1977).

In 1972, in Furman v. Georgia, the Court effectively invalidated all forty-one existing state and District of Columbia capital punishment statutes. Rather than advancing Justice Goldberg’s purported campaign, Furman, in Garland’s view, was a failure: a temporary moratorium on executions that energized and motivated a powerful pro–death penalty movement. But that analysis presumes that the Court should have been or sought to be an “engine of reform.” That is quite wrong. The Court has no agenda of its own, but may (and must) only decide issues that litigants raise in cases over which the Court has jurisdiction.

In my view, unlike Garland’s, when Furman was decided, the justices on the Burger Court were—appropriately—just trying to interpret the Constitution. The difficulties they faced—rather than a reversal in policy—explain unique aspects of the decision. The judgment was announced in a brief unsigned opinion. Each of the nine justices explained his views in a separate opinion. Only two justices endorsed total abolition, and all four dissenters were Nixon appointees, including two who occupied seats once held by Justice Goldberg and Chief Justice Earl Warren.

Garland has little to say about the positive effects of Furman or the five decisions in 1976 that upheld the constitutionality of three state statutes while invalidating mandatory capital punishment laws in North Carolina and Louisiana. Under his “all- or-nothing” approach, he does not consider whether the new state statutes were better or worse than their pre-Furman predecessors.

In his opinion in Furman, Justice Stewart observed that the death sentences before him were “cruel and unusual in the same way that being struck by lightning is cruel and unusual.” The constitutional remedy to deaths being “so wantonly and so freakishly imposed” would narrow the category of death-eligible offenses while enforcing procedural safeguards against the risk that facts unrelated to moral culpability would affect sentencing. More recent decisions have unwisely rejected Justice Stewart’s narrowing approach.

The dynamic supporting a broader application of the death penalty is revealed in cases involving victim-impact statements, felony murder,2 controversy over attitudes toward the death penalty in jury selection, and race-based prosecutorial decisions. As Garland correctly observes, testimony about impact on victims “has been criticized for increasing the emotional temperature of an already highly charged process and exerting additional pressure on the jury to return a death sentence.” In Booth v. Maryland (1987), the Court held that such evidence could serve no purpose other than inflaming the jury and was “inconsistent with the reasoned decisionmaking we require in capital cases.”

Four years later, the Court abruptly overruled Booth in Payne v. Tennessee (1991). Acting “directly contrary to the Court’s rationalizing reforms,” Garland writes, the Court in this decision impeded reasoned jury decision-making. I have no doubt that Justice Lewis Powell, who wrote the Booth opinion, and Justice William Brennan, who joined it, would have adhered to its reasoning in 1991 if they had remained on the Court. That the justices who replaced them did not do so was regrettable judicial activism and a disappointing departure from the ideal that the Court, notwithstanding changes in membership, upholds its prior decisions.

Personnel changes also explain three other important developments in post-Furman jurisprudence that Garland omits. Justice Stewart joined the opinion in Coker v. Georgia, holding that the death penalty may not be imposed for the crime of rape. The year before, he had announced the opinion in Woodson v. North Carolina (1976) barring all mandatory death sentences. He also surely would have joined the majority in Enmund v. Florida (1982) had he still been on the Court. Enmund held that death is not a valid penalty for felony murder if the defendant neither took life, attempted to take life, nor intended to do so.

In its five-to-four decision in Tison v. Arizona (1987) five years later, however, the majority enlarged the category of defendants eligible for execution by holding that major participation in a felony, combined with reckless indifference to human life, may satisfy Enmund’s culpability requirement. Because a decision enlarging the category of death-eligible defendants is so inconsistent with Justice Stewart’s writing, I firmly believe he would not have joined that unfortunate decision.

That is equally true of decisions cutting back on his landmark opinion concerning “death-qualified” juries in Witherspoon v. Illinois (1968). Whereas that case made clear that opposition to the death penalty is not a permissible basis upon which to disqualify or exclude prospective jurors willing to set aside their beliefs in deference to the rule of law, later cases—most notably the 5–4 decision three years ago in Uttecht v. Brown—allow such opposition to be treated as disqualifying because it may substantially impair a juror’s ability to follow the trial judge’s instructions. In Brown, the prosecution spent more than two weeks in voir dire to make sure that the jury was “death qualified.” Justice Stewart used the term “hanging jury” to describe such a panel, which now may be accepted as a fair cross-section of the community.

In 1987, the Court held in McCleskey v. Kemp that it did not violate the Constitution for a state to administer a criminal justice system under which murderers of victims of one race received death sentences much more frequently than murderers of victims of another race. The case involved a study by Iowa law professor David Baldus and his colleagues demonstrating that in Georgia murderers of white victims were eleven times more likely to be sentenced to death than were murderers of black victims. Controlling for race-neutral factors and focusing solely on decisions by prosecutors about whether to seek the death penalty, Justice Blackmun observed in dissent, the effect of race remained “readily identifiable” and “statistically significant” across a sample of 2,484 cases.

That the murder of black victims is treated as less culpable than the murder of white victims provides a haunting reminder of once-prevalent Southern lynchings. Justice Stewart, had he remained on the Court, surely would have voted with the four dissenters. That conclusion is reinforced by Justice Powell’s second thoughts; he later told his biographer that he regretted his vote in McCleskey.

Under Justice Stewart’s approach, a jury composed of twelve local citizens selected with less regard to their death penalty views than occurs today—in that respect, a truer cross-section of the community—would determine individual defendants’ fates. Once chosen, such jurors would not be inflamed by victim-impact statements; they would be insulated from race-based decisions by prosecutors; and they would weigh the offender’s culpability against relevant mitigating circumstances in determining his fate. There are crimes for which such a jury would almost certainly impose a death sentence if so authorized. A portion of the Baldus study that Professor Garland does not discuss found a significant category of extremely serious crimes for which prosecutors consistently seek, and juries consistently impose, the death penalty without regard to race.

The Michigan statute assumed that treason was one such offense. Timothy McVeigh’s bombing of the federal office building named after Judge Murragh in Oklahoma City is surely another. I imagine that attempted assassination of the Pope would qualify, as could murder of a law enforcement officer or prison guard, and perhaps the kind of crime—serial killing of students—described in Garland’s prologue. Garland does not tell us whether he would be an abolitionist in such cases. Rather than treating the death penalty as an all-or-nothing issue, I wish he had commented on the narrower regime that Justice Stewart envisioned.

While he has studiously avoided stating conclusions about the morality, wisdom, or constitutionality of capital punishment, Garland’s empirical analysis speaks to all three. In his account, capital punishment once served the “rationalized state purpose of governing crime” but is now a “resource for political exchange and cultural consumption.” These are both social functions, as Garland states, but of vastly differing moral moment. Deterring crime is a valid reason to punish. Neither political strategy nor deference to the mass media, however, provides an adequate justification for “the more than twelve hundred men and women who have been put to their deaths since executions resumed three decades ago.”

In 1977 in Gardner v. Florida, the Court set aside a death sentence because the trial judge relied on information not disclosed to the defense, a then-permissible practice in noncapital cases. My opinion in that case stated that death is different in kind from other American punishments:

From the point of view of the defendant, it is different in both its severity and its finality. From the point of view of society, the action of the sovereign in taking the life of one of its citizens also differs dramatically from any other legitimate state action. It is of vital importance to the defendant and to the community that any decision to impose the death sentence be, and appear to be, based on reason rather than caprice and emotion.

When I wrote those words I was thinking about individual decisions in specific cases. Professor Garland’s book persuades me that my comment is equally applicable to legislative decisions authorizing imposition of death sentences. To be reasonable, legislative imposition of death eligibility must be rooted in benefits for at least one of the five classes of persons affected by capital offenses.

First, of course, are victims. By definition murder victims are no longer alive and so have no continuing interest.

Second are survivors—family and close friends of victims who often suffer enormous grief and tangible losses. The harm to this class is immeasurable; but punishment of the defendant cannot reverse or adequately compensate any survivor’s loss. An execution may provide revenge and therapeutic benefits. But important as that may be, it cannot alone justify death sentences. We do not, after all, execute drunken drivers who cause fatal accidents.

Third are participants in judicial processes that end in executions—detectives, prosecutors, witnesses, judges, jurors, defense counsel, investigators, clemency board members, and the medically trained personnel who carry out the execution process and whom Garland describes as being somewhat embarrassed by doing so. While support of the death penalty wins votes for some elected officials, all participants in the process must realize the monumental costs that capital cases impose on the judicial system. The financial costs (which Garland estimates are at least double those of noncapital murder cases) are obvious; seldom mentioned is the impact on the conscientious juror obliged to make a life-or-death decision despite residual doubts about a defendant’s guilt.

The fourth category consists of the general public. If Garland’s comprehensive analysis is accurate—that the primary public benefits of the death penalty are “political exchange and cultural consumption”—and as long as the remedy of life imprisonment without the possibility of parole is available, those partisan and cultural considerations provide woefully inadequate justifications for putting anyone to death.

Fifth, of course, is the class of thousands of condemned inmates on death row who spend years in solitary confinement awaiting their executions. Many of them have repented and made positive contributions to society. The finality of an execution always ends that possibility. More importantly, that finality also includes the risk that the state may put an actually innocent person to death.

Two years ago, quoting from an earlier opinion written by Justice White, I wrote that the death penalty represents “the pointless and needless extinction of life with only marginal contributions to any discernible social or public purposes.” Professor Garland identifies arguably relevant purposes without expressly drawing the conclusion that I think they dictate. Perhaps he will tell us his real position in his next installment, which I look forward to reading when (and if) it arrives. In the meantime, I commend Peculiar Institution to participants in the political process.

This Issue

December 23, 2010