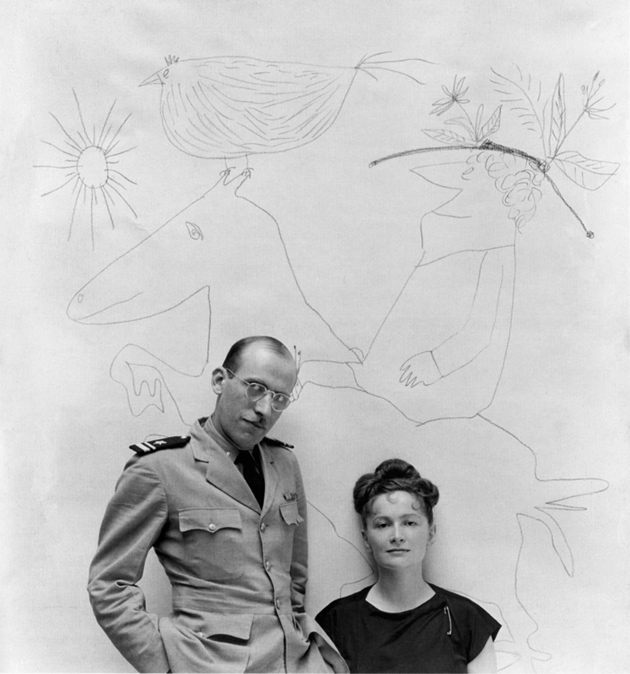

Nina LeenTime Life Pictures/Getty Images

Life magazine’s portrait of the Abstract Expressionist artists known as ‘The Irascibles,’ 1951.

Front row: Theodore Stamos, Jimmy Ernst, Barnett Newman, James Brooks, and Mark Rothko; middle row: Richard Pousette-Dart, William Baziotes, Jackson Pollock, Clyfford Still, Robert Motherwell, and Bradley Walker Tomlin; back row: Willem de Kooning, Adolph Gottlieb, Ad Reinhardt, and Hedda Sterne

At the summit of “The Irascibles,” Life magazine’s 1951 portrait of the Abstract Expressionist painters, stands an imperious-looking woman, the Romanian-born artist Hedda Sterne. She is the only female in the photograph and, in some sense, the most prominent figure—the “feather on top,” as she once put it. Now, at age one hundred, she is the sole survivor. “I am known more for that darn photo than for eighty years of work,” Sterne told me a few years ago. “If I had an ego, it would bother me.” Plus, she said, “it is a lie.” Why? “I was not an Abstract Expressionist. Nor was I an Irascible.”

Who is Hedda Sterne? In 2003, when she was ninety-two and still drawing every day, I interviewed her and tape-recorded the conversation. We met in her apartment on East 71st Street near Third Avenue, where she’d lived for almost sixty years—first with her then husband, Saul Steinberg, the New Yorker artist, and later, beginning in the 1960s, alone. The kitchen and living room were one space. On a table were Sterne’s recent white-on-white drawings. Just about all the other art was Steinberg’s. On a wall hung a trompe l’oeil work spoofing Mondrian; a small table was piled with Steinberg’s wooden “books.” Over the stove hung a faux diploma for cooking, which Steinberg had presented to Sterne in the 1950s, and over the sink was another diploma, for dishwashing. A large carpet of raw canvas lay on the floor, with handwritten lines organized into the squares of a grid. This, I realized, was Sterne’s Diary from 1976, and a perfect emblem of her: a dense fabric of words, drawn with intense concentration, left to be obliterated underfoot.

Recently I listened again to my tape recording. What came through was an artist who, in contrast to almost everyone else in the “Irascibles” photograph, had effectively erased herself. Not only was she not an Abstract Expressionist; she was the anti–Abstract Expressionist, someone who had no use for the cult of personality and personal gesture. As Sarah Eckhardt, curator of “Uninterrupted Flux,” Sterne’s 2006 retrospective, noted, Sterne saw her art as a diary, her eye as a camera finding the extraordinary in the ordinary. Her subjects were mundane. Her palette was spare and muted (tan, ochre, black, white, and blue), her brush more often dry than loaded, her line searching. And at a time when just about every painter who mattered was a heroic abstract artist, or trying to be, she was not.

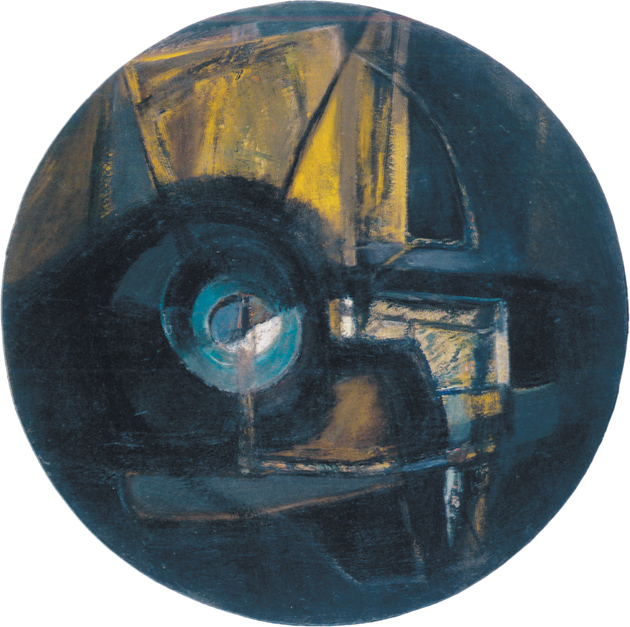

She was enthralled with the look and feel of America. In the late 1940s, when the new abstraction was taking over New York, she painted unbalanced, totemic machines, which, she told Joan Simon in 2007, she saw as portraits of psychic states—“the grasping, the wanting, the aggression.” Then she took up spray paints—blues, reds, blacks, yellows—to depict engine parts, hazy highways, and steel girders as eerie figures and dense networks. (You can see one of these, New York VIII (1954), in the exhibition “Abstract Expressionist New York,” at the Museum of Modern Art until April 25, 2011.) In the 1960s she drew lettuce heads as crazy mazes, as if she were a worm inside, investigating. Whenever she hit a dry period, she made likenesses of her friends (some of which were shown last year at the Pollock-Krasner House on Long Island). Rarely did she paint a pure abstraction. She pointed out that even the webby white-on-white drawings made in the 1990s, when she was practically blind, represented something—the “floaters and flashers” crossing her field of vision.

Sterne was not alone in her absorbed, transforming take on the world around her, which she learned from the Surrealists. What really distinguishes her is her refusal to develop what she tartly termed a “logo” style. And that refusal, Sterne said once, “very much destroyed my ‘career.'” Although Peggy Guggenheim and Betty Parsons championed her, although major museums acquired her work, although Clement Greenberg praised her “nice flatness” and “delicacy” and Hilton Kramer mentioned her “first-class graphic gift,” and although she has had one of the longest exhibition histories of any living artist (seventy years), she is hardly well known. That doesn’t bother her. “I don’t know why, I never was burdened with a tremendous competition and ambition of any kind…. There is this wonderful passage in Conrad’s Secret Agent,” she noted. “There is a retarded young boy who sweeps with a concentration as if he were playing. That was how I always worked. The activity absorbed me sufficiently.”

Advertisement

Hedda Sterne was born Hedwig Lindenberg on August 4, 1910, in Bucharest, Romania, to Simon Lindenberg, a language teacher, and Eugenie Wexler Lindenberg. Her brother, Edouard Lindenberg, became a conductor in Paris. Her parents were Jewish but not religious.

I knew I wanted to be an artist at age five or six. I always drew. At eight I was permitted to study. I always loved Leonardo. Artists were always referred to as great artists. I thought that’s what the profession was. One word: great-artist. There wasn’t one moment in my life when I thought I wanted to be anything else.

In the 1920s she studied art history and philosophy at the University of Bucharest, reading Husserl, Heidegger, Gurdjieff. In the 1930s she took painting lessons with Andre Lhote in Fernand Léger’s Paris atelier. Her early Surrealist collages were shown in 1938, at the 11th exhibition of the Salon des Surindépendants in Paris. In a 1981 interview with Phyllis Tuchman, Sterne described her method: “I would tear paper and throw it and then look at it the way you look at the clouds, and then accent with a pencil what I had seen.” At that exhibition, the Surrealist Victor Brauner, Sterne’s friend, introduced her to Hans Arp, who in turn introduced her to Peggy Guggenheim. Soon after, one of Sterne’s collages turned up in a group show at Guggenheim’s London Gallery.

In 1941, after the Germans occupied Bucharest, Sterne fled to Lisbon and finally to New York City. “In Romania, I escaped a horrible death…. I don’t like to talk about it,” she said. “I was married and separated from a man named Fritz Stern, who changed his name to Frederick Stafford…. I added an e to the name, because I didn’t want to use his name, or lose it.” She became Hedda Sterne and on arrival phoned Peggy Guggenheim. “She was extremely friendly.”

In 1942 Sterne was included in “First Papers of Surrealism,” America’s introduction to Surrealism, curated by André Breton and Marcel Duchamp, and the next year she was in several group shows at Peggy Guggenheim’s Manhattan gallery, Art of This Century. Her first American solo exhibition followed at the Wakefield Gallery—a show of nostalgic egg temperas and drawings in which Sterne, as the critic Dore Ashton noted, exorcised her Romanian past. One, the semi-naif Violin Lesson, depicts a dark, high-ceilinged room inhabited by a teacher and student, bowing violins. The curator was Betty Parsons, the dealer who championed Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb when they were unknowns. She became Sterne’s dealer and introduced her to the Abstract Expressionists.

Sterne threw herself into painting America inside and out. “I immediately got involved in the immediate, the American kitchen, the American bathroom, the American street, you know, its horizontals and verticals, its points and lines.” In the 1940s, “New York was a total delight, a paradise,” Sterne said. “It was enchanting. Tiffany’s in the window didn’t have jewels but exquisite airplane parts. That’s America to me.”

She lived in a studio on Beekman Place, near the river, next door to Peggy Guggenheim and Max Ernst.

I didn’t know that I had moved into the most fashionable neighborhood. There would be a party every week, parties for three hundred people. I thought all New Yorkers lived like that…. All I met were celebrities. But of course, I didn’t see them as such. I saw them as displaced people, like myself…. I would have loved to see real Americans….

At Guggenheim’s she met the Surrealists Yves Tanguy, André Breton, and Hans Richter, as well as Gypsy Rose Lee, William Saroyan, Igor Stravinsky, and Alexander Calder.

I met Mondrian without knowing who he was. Peggy invited me to the party. I sat in a corner, watching. After a while a little old gentleman sat next to me. We were equally bewildered. People came and talked to him with great deference. The party was for him. But he didn’t know at all how to deal with it.

Sterne, along with Elaine de Kooning and Lee Krasner, became one of the few women in a circle of Abstract Expressionist painters that included Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Rothko, and Franz Kline. “The guys would say, ‘Oh, you are one of us!’ or ‘You paint just like a man.’ That was supposed to make me die with being pleased.” In fact, though, Sterne was painting nothing like them. Her teetering, machine-like constructions had more to do with Paul Klee and Alexander Calder. Yet she liked her new circle of friends and found that the macho, hard-drinking New York School of legend was in fact “no more a boy’s world than what I have encountered in my entire life…no, on the contrary, it was an agreeable surprise.”

Advertisement

Sterne’s recollections of individual painters often run counter to the usual myths: “Pollock had the reputation of being a drunk,” but she remembered how “he would spend an evening or two with people who had small children” and “worried when people talked too loud that it would disturb the sleeping children.” Franz Kline would tell fantastic stories about his cat for hours.

She became especially close to Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko, but her recollections of them are not always complimentary. Rothko “was a very neglected-looking man, but not Bohemian—you know, spots on his tie.” His brothers belittled his art, indeed art in general. One of them once refused to visit the Statue of Liberty, saying, “I don’t like sculpture.” That only fueled Rothko’s grim determination. “He was always a sad man and very depressed. Insanely ambitious. Even after he was a success, in the end he didn’t have enough.”

Newman, who wanted to be mayor of New York when he was young, was one of the forces behind the 1951 photograph of the Abstract Expressionists. “There was a meeting of artists,” called by Newman and Gottlieb in 1950, Sterne said.

They decided that the Metropolitan Museum does not encourage modern art. They wrote a letter of protest [which a group of artists signed] and gave it to every newspaper in town. Emily Genauer, the art critic of The Herald Tribune, kind of tongue-in-cheek, mockingly called the group “The Irascibles.” The photographer of Life magazine followed the story and invited everybody to come…. She created a kind of amphitheater of chairs. I was the last, like a feather on top.

Sterne appears to be the supreme Irascible, commanding the troops, but the situation was different. In her interview with Tuchman, Sterne said, “Well, the girl at Life magazine had prepared the chairs completely…. I came in rather late and she told me, ‘stand there,’ that’s all.” With no chair for her, she stood on a table. That photo, she added, is “probably the worst thing that happened to me.” The boys weren’t too happy about it either. “They all were very furious that I was in it because they all were sufficiently macho to think that the presence of a woman took away from the seriousness of it all.”

Sterne’s closest friend by far was a fellow artist from Romania, Saul Steinberg. “We didn’t know each other in Romania. Saul left at the age of seventeen. I was four years his senior. A girl, nineteen, doesn’t see a boy, fifteen, very much. He went to Italy first. We had different lives. But I knew of him,” she said. “I saw his cartoons in Europe.” She remembers their first meeting, in 1943:

He came to lunch one day and stayed. It was less weird than that would be now. I was living at 410 East 50th Street, right near the river, five flights up. He was not yet in uniform; this was before he entered the Navy. I had a collection of children’s art on the wall. He was very pleased. He thought we are going to see eye to eye.

Sterne analyzed her instant rapport with Steinberg: “I grew up out of refusals—‘I don’t want this.’ Saul had the same horrors and taboos. It took about a half-hour and we were old friends.” They married in 1944.

His thinking and his drawing were completely one…. I would have liked to have what he had…. I never saw him draw a line I didn’t think was delightful…. I didn’t just like it. I would hyperventilate.

In 1947, they spent time in Vermont, where Sterne discovered the farm equipment that became a staple of her work through the 1950s. (In these paintings she seemed to cannibalize machines for their parts—tractor seats, bellows, crane claws—to create new anthropomorphic structures.) They had a stint in Hollywood (where Steinberg was supposed to have designed the artwork for An American in Paris). And in the mid-1950s they saw America, by car:

Whenever you went on a drive with Saul you never went where you intended. He either lost his way or something. We saw all fifty states by car in three and a half months. The only place we didn’t get to was Hawaii…. We ended in an Indian reservation in an Indian hotel where you had to pay extra for sheets.

Steinberg discovered American baseball and bank buildings. Sterne found blurry, swirling highways.

“This was a hardworking period for me.” Sterne said of the 1950s. “I painted all day. I would work eight hours a day. Saul would never work more than a half-hour to three quarters of an hour. When it wasn’t total play and amusement, he stopped.” On top of that, she said, “I had dinners for fourteen. I cooked and cleaned, did everything myself, once or twice a week, or maybe once every three weeks…. Saul became more and more famous. He knew all The New Yorker people, the writers and cartoonists, and movie people”—Charlie Addams, Cobean, William Steig, Peter Arno, Ian Frazier, Dwight McDonald, Harold Rosenberg, E.B. White, Katherine White—and they all came to dinner.

Steinberg, in honor of Sterne’s efforts, made her the two diplomas, complete with seals and signatures—one for dishwashing, one for cooking. When I asked whether she was particularly good at dishwashing, Sterne replied: “He was indulgent.” Then, she joked: “For a long time I functioned only with a certificate for cooking. For me cooking is an extension of love. I never cook, you know, I cook for him. If we went to a restaurant and he liked something I would find out how it’s made. My preoccupation was doing things he liked.”

Steinberg left in 1961. She recalled their marriage, without rancor, as “sixteen years of infidelity,” and as “a kind of partly pleasant, partly difficult interlude” to a long friendship. At the separation, “there was never anything practically said, except that he just moved out. There was no divorce. No anger. We went together to friends’ houses to tell them…. Our friendship kept growing. We talked on the phone twice a day,” she said, adding, “Saul would like to have a harem. He knew how to add, not subtract.”

In the 1960s Sterne began what she called “her reclusive life,” drawing, painting, and seeing a few friends.

I remember when Saul left, there was a friend of his, a movie man, and I gave him a party with New Yorker writers. It was the first one without Saul. I made a big dish of paella. After everyone left, I found the dish of paella. I forgot to serve it…. I was without him and someone would always want to stay on. And there was a great problem to get the drunk out. I stopped giving parties totally…. The last opening I went to was in the 1970s, when Saul had a show at the Whitney.

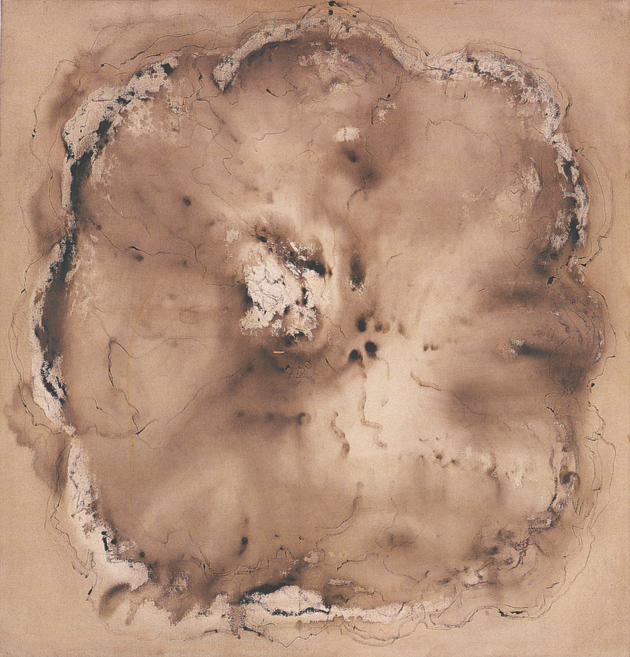

Her painting changed as well. In the 1960s, just as abstract painting was being dethroned by Pop, she turned more abstract. She began the so-called “vertical-horizontals”—tall canvases with horizontal bands of color reminiscent of Rothko’s work. One such painting begins at the top with a broad tan stripe, melds into fawn color, runs into a band of yellow, a thin brown, another fawn color, another brown, and then, little by little, grays out. It looks abstract, but Sterne denies it: “Mondrian and Albers are abstract. My work is always a reaction to a visual experience.” In 1963, she lived in Venice on a Fulbright and studied glass and its effects on light in the Murano factory. “I was obsessed by it,” she said. The works that emerged resemble modern geometric stained glass drained of color.

In the late 1960s Sterne swung back to more figurative work. She produced her Lettuces, huge, leafy paintings and drawings that look like Eva Hesse’s early works on paper. She also created an installation, first in her apartment, then at Betty Parsons Gallery—scores of anonymous, colorless faces, drawn in acrylic paint on canvas, looking outward, unframed on the wall. The 1970 exhibition, titled “Hedda Sterne Shows Everyone,” caused a small scandal akin to the larger one Philip Guston caused with his paintings of Klansmen at the Marlborough Gallery the same year. She was seen as a traitor to abstraction.

She turned further inward and began using written texts. She put raw canvas on the floor, divided it into a grid of days, and filled it with notes and quotes. It could be walked on, like some works by Carl Andre. One square had this text:

an animal on matto grosso has big flat feet which produce a musical sound as it walks and a trunk with which it sucks butterflies on the wing. its mane is very thick and it always runs away from the color blue.

By the mid-1990s, thanks to cataracts and macular degeneration, Sterne was almost blind. She stopped painting and began drawing—not with stronger contrasts, as one might imagine, but with white crayons on white paper, aided by a magnifying glass. She was drawing, she told me, “without any external stimulus, only internal stimulus.” But she was still a figurative artist, representing her own paling vision.

When I spoke with Sterne in 2003, three years before her retrospective opened at the Krannert Art Museum in Illinois, she was leading a full and solitary life:

Drawing is continuity. Everything else is interruption, even the night and sleep. I walk in the house like a lion everyday to keep healthy. I work out. I defend myself. I’m “invalidated.” …I can die at any moment. But I still learn. Every drawing teaches me something….

The following year she had a stroke that ended drawing for her, except as something to do in her head.

Leonardo drew things to explain them to himself…. That’s an essential quality of any work of art, the authenticity of the need for understanding. I once told Barney [Newman] a story which he wanted to adopt as the motto for the Abstract Expressionists: A little girl is drawing and her mother asks her what are you drawing? And she says, “I’m drawing god.” And the mother says, “How can you draw god when you don’t know what he is?” And she says, “That’s why I draw him.”

When I was young, I tried very hard. I wept every day in the studio because there was such a distance between what I wanted to do and what came out. Now I’m at peace, because of old age. It flows calmly now. I meditate for a long time. I work against ego. I think ego is an obnoxious bother. To a great extent I have lost all interest in this fiction, Hedda Sterne.

This Issue

December 23, 2010