James Kaplan’s Frank: The Voice is authentically a page-turner, a strident tabloid epic constructed out of facts—or more precisely out of the disparate and sometimes contradictory testimony of scores of participants in Frank Sinatra’s early life. There is certainly enough testimony to choose from; pieces of Sinatra, variously skewed and distorted, are scattered all over the latter part of the twentieth century. But they hardly converge into a unified portrait: confronted with the multitude of Sinatras that one must attempt to resolve into a single plausible person, there is a gathering sense of unsettling dissonance quite at odds with the perfected harmonies of his greatest recordings.

Kaplan limits himself to the first third of Sinatra’s trajectory, the rise and fall and resurrection preceding the long run of now-classic albums for Capitol, the raucous heyday of the Rat Pack, and the final enthronement as Chairman of the Board. His book is thus a Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man—following Sinatra at close range up to the moment when he retrieves a faltering career by winning the supporting actor Oscar for From Here to Eternity—except that the subject refuses to sit still long enough to provide a stabilized image.

The broad plot line has the advantage of an arc of compelling simplicity: a young man emerges out of nowhere driven by limitless desire to succeed, gets everything as if by magic, comes close to losing it all, then gets it back with interest. In outline it is a triumphal narrative with the same appeal as the life of Caesar or Napoleon, with the further advantage that in the realm of show business such a story can have a happy ending, concluding not with exile or assassination but with a legacy’s eternal perpetuation, as The Voice continues to permeate the world through reissued recordings.

When a columnist refers to Sinatra as a “demigod,”1 the facetiousness may mask a genuinely worshipful emotion; Sinatra’s stature as emblem of uncontestable supremacy and durability continues to make him a mythic hero. It was not nothing to have occasioned the ubiquitous unattributed bit of wisdom: “It’s Sinatra’s world, the rest of us just live here.” The conscious aim of his existence may well have been to become the only individual who could elicit such an encapsulation. Being the best singer ever wasn’t the half of it; Sinatra as folk hero is the man who remolds the world according to his own desires, breaking all rules and laying down new ones at whim, and finally, with the supreme self- indulgence of one who cannot be touched, epitomizing and even mocking his own cliché in endless encores of “My Way.”

But triumph is not precisely Kaplan’s subject. He wants to get inside the headlong rush of Sinatra’s career, and find the inner connections in a life ranging from unparalleled lyrical expression to unpredictable violent explosiveness; he tries to slow down the familiar show-biz montage long enough to wrest some sense of actuality from anecdotes many of which have been told and retold many times over. What he gets to—by means of a piling up of day-to-day, night-to-night detail that yields an almost neurological realism—is a core of discomfort and anxiety, whose outward manifestation as often as not was a barely restrainable impulse to control, if not to attack. Sinatra, a solitary who ruled crowds by seductive magnetism and surrounded himself with courtiers, had once been an adolescent alone in his room listening to Bing Crosby on his Atwater-Kent, and imagining how he would conquer the world through the power of his voice. Even he, though, could hardly have imagined the riotous effect he would have on the teenage girls of America, or that it was his fate to usher in the era of a new sort of mass idolatry.

Kaplan shows the young Sinatra as an almost infinitely ambitious neat freak whose sense of order ultimately extended to every aspect of his life, present and future: “Virtually every move he made in his life had to do with the furtherance of his career.” The smallest uncertainty made things uncomfortable both for him and for those around him: “When he was afraid, he liked to make others jump.” The power of the talents he discovered in himself—the talent for singing and the far greater talent for selecting, understanding, and interpreting what he sang—was harnessed to a mass of suspicions, resentments, and self-protective rages. In the recording studio he would savor the disciplined release of an unfathomably powerful force: a perfectionist who often enough achieved something like perfection, he made it his business to create a situation as close as he could get to total control. Elsewhere discipline was erratic and situations often got out of hand. “Frank’s entire life,” Kaplan sums up, “seemed to be based on the building and the release of tension. When the release came in the form of singing, it was gorgeous; when it took the form of fury, it was terrible.”

Advertisement

The book’s tone often approaches the melodramatic, but it is melodrama honestly come by. This was a life lived, at least in these less guarded early years, as if to leave just such a gaudy record behind, as the producer Mitch Miller (one of many colleagues whom Sinatra finally put firmly in his place) once suggested:

Frank was a guy—call it ego or what you want—he liked to suffer out loud, to be dramatic. There were plenty of people, big entertainers, who had a wild life or had big problems, but they kept it quiet. Frank had to do his suffering in public, so everyone could see it.

If Sinatra, despite many striking screen performances, from Eternity’s Maggio to The Manchurian Candidate’s Major Marco, never quite created a movie persona equal to his gifts, it was because his real movie was his life, a spectacle whose excesses, emotional swings, casual cruelties, and hair-trigger outbursts went well beyond anything Hollywood was likely to attempt.

And he did not live it alone: while the book’s central focus might be taken as the difficulty of being Frank Sinatra, it was, by Kaplan’s reckoning, clearly not much easier being Tommy Dorsey (“ever restless, insatiably ambitious”) or Buddy Rich (“volatile, egomaniacal”) or Lana Turner (“an empty shell of a human being”) or Nelson Riddle (“a dour, caustic, buttoned-up Lutheran”) or Jimmy Van Heusen (“foul-mouthed, obsessed with sex and alcohol”) or, least of all, Ava Gardner, who when she enters the scene takes over the book pretty much the way she seems to have taken over Sinatra’s psyche.

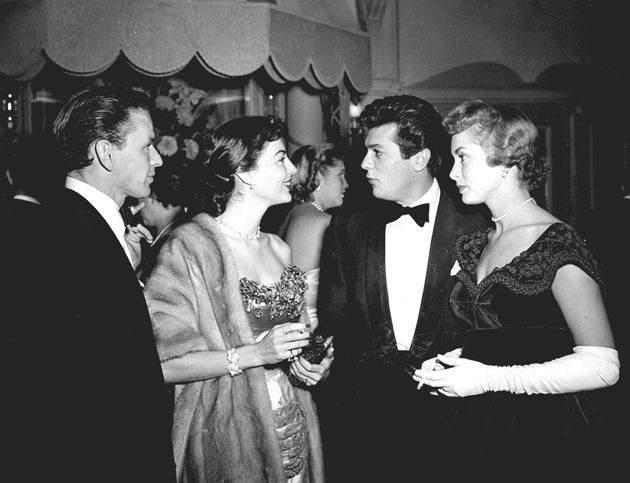

We find ourselves—not for the first time, and surely not the last—deep in the phantasmagoric realm of twentieth-century stardom, wandering among dream-fabricators whose own lives seem dreamed. Frank Sinatra dances with Lana Turner and stares at Ava Gardner (freshly divorced from Artie Shaw following her earlier divorce from Mickey Rooney) while she dances with Howard Hughes. Among all these adepts of self-invention, Sinatra triumphs by the consciously directed energy and single-minded calculation he brings to the task—until (in the legend that his life has become) he comes up against the insuperable Ava. That at least is one way to read the evidence; the other would be to imagine Sinatra maneuvering always on the edge of chaos, as bewildered as any onlooker by the gale force of his early trajectory.

Kaplan starts the story straight out of the womb, with Sinatra’s difficult birth, a birth that left permanent scars and deformities (a misshapen left ear) and that both he and his mother evidently barely survived: “They just kind of ripped me out and tossed me aside,” he once confided to a lover, still nursing resentment at being neglected by the doctor who was struggling to save his mother’s life. The trauma of birth is succeeded by the trauma of an alternately abusive and coddling mother-and-son relationship—she liked to dress him in Fauntleroyish clothes when not beating him with a stick—that Kaplan sees as the “textbook” source of Sinatra’s “infinite neediness, an inability to be alone, and cycles of grandiosity and bottomless depression.”

We are given a quick and monstrous sketch of Dolly Sinatra, who is made to loom implicitly in gargoyle fashion over all her son’s subsequent doings, having implanted in him, by her tyrannical capriciousness and relentless manipulation, a permanent distrust of intimate relationships. Within her Hoboken community, as midwife, sometime abortionist, local operative of the Democratic party, hanger-on of mob-connected bootleggers at the bar she opened with her husband Marty in the 1920s, she displayed the same ferocity of ambition that Sinatra would bring to bear on a grander scale. Marty Sinatra, by contrast—an illiterate Sicilian-born prizefighter whose fighting career petered out early—impresses most by his absence and silence. “I’d hear her talking and him listening,” Sinatra would recollect. “All I’d hear from my father was like a grunt…. He’d just say, Eh. Eh.”

However tough Hoboken may have been, Sinatra, thanks to his mother, enjoyed a fairly privileged status: he had a charge account at a major department store, an extensive wardrobe, and, at eleven, his own bedroom and his own state-of-the-art radio. By his own account he had, as well, access to a different kind of privilege: “Late in life Sinatra told a friend that as a child he had heard the music of the spheres.” That inner concert was supplemented before long by the big-band jazz that was flowering just as he entered adolescence. He was permeated by the work of all those musicians—by Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Art Tatum, Fats Waller, Tommy Dorsey, and perhaps most importantly Billie Holiday—just as later on (after being impressed by Jascha Heifetz’s violin technique) he would soak up the classical music that he collected and, it seems, listened to with the same fanatical attention to detail he brought to everything musical. (His musical knowledge was acquired by ear, and though he made recordings as a conductor he never really learned to read music.) He did not finish high school; he made no serious attempt to work at anything other than singing, and claimed to have had from the start an absolute conviction that he would succeed. After his triumphant opening at New York’s Riobamba club in 1943 he told a young reporter: “I’m flying high, kid. I’ve planned my career. From the first minute I walked on a stage I determined to get exactly where I am.”

Advertisement

Stories like this often gain some of their dramatic effectiveness from the recounting of early obstacles and setbacks, but in truth Sinatra’s career at its outset has the monotony of what in retrospect seems like nearly unopposed success. He did the requisite scuffling, but by nineteen he was already appearing on Major Bowes’s radio amateur hour as a member of the short-lived Hoboken Four, and then touring under the major’s aegis; at twenty-three he joined Harry James’s band (insisting on keeping his own name when James wanted to call him Frankie Satin); the same year he left James for Tommy Dorsey, of whom he said: “The only two people I’ve ever been afraid of are my mother and Tommy Dorsey.” In 1940 he had his first number one record (“I’ll Never Smile Again”) and in 1942, having in turn left Dorsey, he made what turned out to be a legendary opening as a solo act at the Paramount. Jack Benny, who introduced him on stage, described what happened: “I thought the goddamned building was going to cave in. I never heard such a commotion…. All this for a fellow I never heard of.”

At every step Sinatra was learning from everyone he encountered, perfecting himself as a performer, and savoring, on stage and off, the adulation of what his publicist George Evans called “a great herd of female beasts…all in heat at once.” (It was Evans who helped orchestrate the apparently random hysteria that swept over Sinatra’s audiences, and who certified his singularity by tagging him as The Voice.) He became a technician of breath control; a deeply informed student of the American songbook, with a singular capacity to discern hidden beauties in outdated or discarded material; a song interpreter who actually (in an era of pretty voices crooning lyrics presumed to be interchangeable) cared about what the words meant and how each played its part in a narrative arc.

A 1939 review in Metronome remarked on “the pleasing vocals of Frank Sinatra, whose easy phrasing is especially commendable,” but of course the phrasing had not been easily arrived at. He had realized early on that the relaxed fluidity of his role model Bing Crosby was not a style he could ever duplicate. His singing emerged from difficulties confronted. The carefully nurtured clarity of his diction, the precise accentuation by which he marked out the syntactic logic of the lyrics, insisted from the start that the words actually be heard. His singing could never be background music: something was being imparted, in a seamless wedding of word and tone, and attention had to be paid. He could afford to go easy on the schmaltz, and the emotional content of the songs came through all the more clearly.

It was as if he removed all obstacles separating the song from the listener. He did not so much express himself as expose, with objectivity and an almost oppressive clarity, the full measure of what the song had in it. Once he had sung a song—“Begin the Beguine” or “Autumn in New York” or “The Song Is You” or “A Foggy Day” or “Violets for Your Furs”—it stayed sung, in just his way, with every breath and rhythmic accent and knowing slur and catch in the throat permanently attached to it.2

The war years were Sinatra’s moment of early glory; he dominated the record charts, had his own radio programs where he hawked Vimms Vitamins and Lucky Strikes; signed a generous five-year contract with MGM; and headlined stage performances in front of ever wilder audiences, culminating in the so-called Paramount Riot of October 1944, a year in which he earned the then-enormous income of $84,000. George Evans’s publicity machine conjured up an appropriate storybook image of Sinatra as boyishly enthusiastic young husband and father, enjoying a cozy domestic life with his teenage sweetheart Nancy Barbato and their two children Nancy and Frank Jr. (a third, Tina, would be born in 1948). His 1945 hit “Nancy with the Laughing Face,” by Phil Silvers and Jimmy Van Heusen, became a convenient emblem of family happiness, whether its object was taken to be his wife or his daughter, and even though, as Kaplan reveals, the song was originally called “Bessie with the Laughing Face” and was retitled to curry favor with Sinatra.

In any event his private life was of a rather different character; he was rarely home and had established the pattern of sexual compulsiveness that provides the ground bass for Kaplan’s narrative, a compulsiveness fully in keeping with Sinatra’s insomnia, his fear of boredom, his fear of being alone. “In truth,” Kaplan writes,

there were probably even more affairs than the hundreds he’d been given credit for…. His loneliness was bottomless, but there was always someone to try to help him find the bottom.

Booze helped too—and books. He had developed the habit of reading on the long bus trips between gigs, and had by the mid-1940s evolved into a left-leaning intellectual of sorts, attentive to public affairs and a spokesman for racial and religious tolerance. His gorgeous interpretation of Earl Robinson’s “The House I Live In,” with its Popular Front resonance (“But especially the people—that’s America to me”), overwhelms by its impression of utter sincerity—but then, so does his interpretation of “Nancy with the Laughing Face.”3

In the midst of a life of desperate restlessness Sinatra managed to project, as needed, whatever personality the situation required. A New York Times critic, Isabel Morse Jones, was biased against Sinatra until she interviewed him in 1943 and came away writing things like: “He is just naturally sensitive…. He is a romanticist and a dreamer and a careful dresser and he loves beautiful words and music is his hobby. He makes no pretensions at all.” The sometimes vicious columnist Louella Parsons was persuaded that Sinatra was “warm, ingenuous, so anxious to please.” Sinatra had the ability to convince nearly everyone of his sincerity, let them down over and over, and still win them back. His relentlessly self-serving behavior could provoke disappointment tinged with disbelief, except among those intimates who knew him best and whose task it was to cater to his mood swings. They called him The Monster.

Sinatra’s irresistible ascent, coupled with the unlovely portrait Kaplan paints of him, begins to generate a certain monotony until the moment in the late 1940s when he starts to lose altitude, to the delight of so many who had been repelled by his perceived arrogance, skeptical of his having gotten out of the draft thanks to a perforated eardrum, and appalled by, or envious of, the “squealing, shouting neurotic extremists who make a cult of the boy.” The latter characterization was by the columnist Lee Mortimer, who would earn a role in Sinatra’s career crisis when Sinatra, enraged by repeated jabs in Mortimer’s column, assaulted him outside Ciro’s restaurant in Los Angeles in April 1947, administering an apparently fairly ineffectual beating while calling him (in one version) a “degenerate” and “fucking homosexual.”

The negative publicity attendant on this incident was nothing compared to the cloud cast by Sinatra’s presence in Havana during the notorious Mafia conclave at the Hotel Nacional in February of the same year. His unconcealed socializing with a group including Willie Moretti (an old New Jersey acquaintance of Sinatra’s) and Lucky Luciano caught the attention of the journalist Robert Ruark, who proceeded to draw national attention to Sinatra’s

curious desire to cavort among the scum…. Mr. Sinatra, the self-confessed savior of the country’s small fry…seems to be setting a most peculiar example to his hordes of pimply, shrieking slaves.

(Kaplan makes somewhat less of such mob ties than other writers have done, chalking them up in large part to the adulation of a lifelong wannabe, while acknowledging the likelihood of many favors given and received.)

Bad news piled up. A trade journal asked in 1948: “IS SINATRA FINISHED?” He was having vocal problems and at times losing his voice altogether. Audiences at his shows had already been shrinking; his record sales were off; newcomers like Perry Como and Eddie Fisher were eclipsing him. His recent movies had been bombs, and when The Frank Sinatra Show debuted on CBS in 1950, Variety took note of its “bad pacing, bad scripting, bad tempo, poor camera work and overall jerky presentation.” After his first marriage ended in divorce, he had to give up his Palm Springs house and was often broke. The IRS was after him for unpaid taxes.

Right-wing columnists who had always despised him redoubled their attacks in a rapidly changing political climate. (Sinatra’s demoralization can be gauged from an internal FBI report from 1950 which claims that he offered the agency his services in providing confidential reports on “subversive elements” in the entertainment field; the offer was rejected.) Estes Kefauver called him before his committee investigating organized crime, although he was permitted to testify in secret. (Did he know Frank Costello? “Just to say hello.” Joe Adonis? “Just ‘hello’ and ‘goodbye.'”) Within a few years Sinatra had lost his movie contract with MGM, his radio contract for Your Hit Parade, his television contract with CBS, his agency contract with MCA, his recording contract with Columbia.

At the same time that his career was apparently falling apart, his affair with Ava Gardner had gone public and by 1951 they were married, a marriage that would last just under two years (a good deal longer than Ava’s two previous marriages). This well-publicized and subsequently much-analyzed debacle—a series of violent quarrels and passionate (and, eventually, not so passionate) reunions, punctuated by a number of apparently halfhearted suicide attempts or threats on Sinatra’s part—has become the crucial episode in capsule lives of Sinatra, in which he plumbs the limits of suffering and emerges a great artist, boyish seductiveness burned away into a harsher and more rueful emotional realism. (“Ava taught him how to sing a torch song,” in Nelson Riddle’s formulation.)

Kaplan dutifully chronicles the endless comings and goings of a marriage marked mostly by separation, and sums up Ava’s contribution to Sinatra’s life:

Like Frank, she was infinitely restless and easily bored. In both, this tendency could lead to casual cruelty to others—and sometimes to each other. Both had titanic appetites, for food, drink, cigarettes, diversion, companionship, and sex…. Both distrusted sleep…. Both hated being alone.

It might suffice to say that he had met the female Frank Sinatra—a woman he could neither dominate nor leave alone—and leave it at that. In a cold light this pair of ennui-ridden insomniacs might seem a poor substitute for Antony and Cleopatra, but who would want to see them (any more than Antony and Cleopatra) in a cold light? If they exist for us at all it is as figures of myth, or what in this latter era has passed for such. Ava Gardner persists as a presence made numinous by the cinematographers who so lovingly framed and lighted her in The Killers, Pandora and the Flying Dutchman, and Mogambo. However indifferent she may have been to movie stardom as a career, she was clearly not indifferent to the power she was able to exert just by being there, and still exerts: just as The Voice continues to create an idealized world through its reverberations, resistant to even the most squalid of biographical details.

To get at anything like an anchored sense of reality in that maze of reflections and echoes—that peculiar arena where their inner lives were parsed on a daily basis by the odious likes of Walter Winchell and Louella Parsons and George Sokolsky—must have been as difficult for Gardner and Sinatra as for the audience of the open-ended public spectacle in which they played out their roles.

One closes Kaplan’s book with a dark and sodden sense of the world in which those lives were improvised, a world neatly summed up in an offhand remark attributed to the agent “Swifty” Lazar: “Losers have the time to be nice.” The glittery splendor of Sinatra’s Oscar-winning moment of redemption for his performance as Maggio has little warmth in it, to say the least. “Then, turning up the volume on one of the records he made not long afterward, after he had recouped his losses and settled into a second and more lasting preeminence, it all gets washed away by a wave of upbeat insouciance—

When skies are cloudy and gray

They’re only gray for a day

So wrap your troubles in dreams

And dream your troubles away

—as Sinatra works with Nelson Riddle to create a separate reality invulnerable to ordinary suffering, the reality of song at the heart of his maze.4 And then, again with Nelson Riddle, at the end of one of those ballads that he seems to slow down to a pace almost intolerably slow, so as to sound the very bottom of each note and each thought, he inscribes in the final phrase what might be taken as a symbolic suicide note, a record of inner transcendence, or a demonstration of how deeply he had lost himself in his art: “‘Scuse me while I disappear.”5

This Issue

February 10, 2011

-

1

Bob Shemeligian, “Rat Pack Made Copa Room Special,” Las Vegas Sun, August 5, 1996. ↩

-

2

For “Begin the Beguine,” “Autumn in New York,” and “The Song Is You,” see the box set A Voice in Time, 1939–1952 (Sony, 2007); for “A Foggy Day” and “Violets for Your Furs,” see Songs for Young Lovers (Capitol, 1954). ↩

-

3

“The House I Live In,” as recorded for the 1945 short film directed by Mervyn LeRoy, can be found in the box set Sinatra in Hollywood, 1940–1964 (Warner Bros./Reprise, 2002). ↩

-

4

“Wrap Your Troubles in Dreams,” Swing Easy! (1954). ↩

-

5

“Angel Eyes,” Frank Sinatra Sings for Only the Lonely (1958). ↩