1.

Since the summer of 2007, when Mad Men premiered on the cable station AMC, the world it purports to depict—a lushly reimagined Madison Avenue in the 1960s, where sleekly suited, chain-smoking, hard-drinking advertising executives dream up ingeniously intuitive campaigns for cigarettes and bras and airlines while effortlessly bedding beautiful young women or whisking their Grace Kelly–lookalike wives off to business trips in Rome—has itself become the object of a kind of madness. I’m not even referring to the critical reception both in the US and abroad, which has been delirious: a recent and not atypical reference in the Times of London called it “one of the…best television series of all time,” and the show has repeatedly won the Emmy, the Golden Globe, the Screen Actors Guild Award, the Writers Guild of America Award, and the Producers Guild of America Award for Best Drama Series. (A number of its cast members have been nominated in the various acting categories as well.) Rather, the way in which Mad Men has seemingly percolated into every corner of the popular culture—the children’s show Sesame Street has introduced a Mad Men parody, toned down, naturally, for its tender viewers—suggests that its appeal goes far beyond what dramatic satisfactions it might afford.

At first glance, this appeal seems to have a lot to do with the show’s much-discussed visual style—the crisp midcentury coolness of dress and decor. The clothing retailer Banana Republic, in partnership with the show’s creators, devised a nationwide window display campaign evoking the show’s distinctive 1960s look, and now offers a style guide to help consumers look more like the show’s characters. A nail polish company now offers a Mad Men–inspired line of colors; the toy maker Mattel has released dolls based on some of the show’s characters. Most intriguingly, to my mind, Brooks Brothers has partnered with the series’s costume designer to produce a limited edition Mad Men suit—which is, in turn, based on a Brooks Brothers design of the 1960s.

Many popular entertainments, of course, capitalize on their appeal by means of marketing tie-ins, but the yearning for Mad Men style seems different from the way in which, say, children who are hooked on the Star Wars series yearn to own Darth Vader action dolls. The people who watch Mad Men are, after all, adults—most of them between the ages of nineteen and forty-nine. This is to say that most of the people who are so addicted to the show are either younger adults, to whom its world represents, perhaps, an alluring historical fantasy of a time before the present era’s seemingly endless prohibitions against pleasures once taken for granted (casual sex, careless eating, excessive drinking, and incessant smoking); or younger baby boomers—people in their forties and early fifties who remember, barely, the show’s 1960s setting, attitudes, and look. For either audience, then, the show’s style is, essentially, symbolic: it represents fantasies, or memories, of significant potency.

I am dwelling on the deeper, almost irrational reasons for the series’s appeal—to which I shall return later, and to which I am not at all immune, having been a child in the 1960s—because after watching all fifty-two episodes of Mad Men, I find little else to justify it. We are currently living in a new golden age of television, a medium that has been liberated by cable broadcasting to explore both fantasy and reality with greater frankness and originality than ever before: as witness shows as different as the now-iconic crime dramas The Sopranos and The Wire, with their darkly glinting, almost Aeschylean moral textures; the philosophically provocative, unexpectedly moving sci-fi hit Battlestar Galactica, a kind of futuristic retelling of the Aeneid; and the perennially underappreciated small-town drama Friday Night Lights, which offers, among other things, the finest representation of middle-class marriage in popular culture of which I’m aware.

With these standouts (and there are many more), Mad Men shares virtually no significant qualities except its design. The writing is extremely weak, the plotting haphazard and often preposterous, the characterizations shallow and sometimes incoherent; its attitude toward the past is glib and its self-positioning in the present is unattractively smug; the acting is, almost without exception, bland and sometimes amateurish.

Worst of all—in a drama with aspirations to treating social and historical “issues”—the show is melodramatic rather than dramatic. By this I mean that it proceeds, for the most part, like a soap opera, serially (and often unbelievably) generating, and then resolving, successive personal crises (adulteries, abortions, premarital pregnancies, interracial affairs, alcoholism and drug addiction, etc.), rather than exploring, by means of believable conflicts between personality and situation, the contemporary social and cultural phenomena it regards with such fascination: sexism, misogyny, social hypocrisy, racism, the counterculture, and so forth.

Advertisement

That a soap opera decked out in high-end clothes (and concepts) should have received so much acclaim and is taken so seriously reminds you that fads depend as much on the willingness of the public to believe as on the cleverness of the people who invent them; as with many fads that take the form of infatuations with certain moments in the past, the Mad Men craze tells us far more about today than it does about yesterday. But just what in the world of the show do we want to possess? The clothes and furniture? The wicked behavior? The unpunished crassness? To my mind, it’s something else entirely, something unexpected and, in a way, almost touching.

2.

Mad Men—the term, according to the show, was coined by ad men in the 1950s—centers on the men and women who work at Sterling Cooper, a medium-sized ad agency with dreams of getting bigger; when the action begins, in the early 1960s, the men are all either partners or rising young executives, and the women are secretaries and office managers. At the center of this constellation stands the drama’s antihero, Don Draper, the firm’s brilliantly talented creative director: a man, we learn, who not only sells lies, but is one. A flashback that comes at the end of the first season reveals that Don is, in fact, a midwestern hick called Dick Whitman who profited from a moment of wartime confusion in Korea in order to start a new life. After he is wounded and a comrade—the real Don Draper—is killed, Dick switches their dog tags: the real Don’s body goes home to Dick’s grieving and not very nice family, while Dick reinvents himself as Don Draper. (In the kind of cultural winking in which the show’s creators like to indulge, the small town in which Dick Whitman’s family await his body is called “Bunbury”—the term that the male leads in Oscar Wilde’s Importance of Being Earnest use for their double lives.)

This back story, as rusty and unsubtle a device as it may be, helps establish the pervasive theme of falseness and hypocrisy that the writers find not only in the advertising business itself, but in the culture of the Sixties as a whole just before the advent of feminism, the civil rights movement, and the sexual liberation of the 1970s. (In a typical bit of overkill, the writers have made the ingenious adman the son of a prostitute.) The four seasons that have been aired thus far trace the evolution of the larger society even as the secret that lurks behind Don’s private life becomes a burden that’s increasingly hard to bear. Female employees become more assertive: one secretary, Peggy Olson, who’s not as pretty as the others, becomes a copywriter—to the dismay of the office manager, a red-headed bombshell called Joan Holloway, who’s a decade older and can’t understand why anyone would want to do anything but marry the boss. One of the fabulously hard-drinking executives finally goes into AA. The firm considers the buying power of the “Negro” market for the first time.

Meanwhile, Don wanders from career triumph to career triumph and from bed to bed, his preternatural understanding of what motivates consumers grotesquely disproportionate to any understanding of his own motives; and back home, his gorgeous blond wife, Betty, a former model from the Main Line, is starting to chafe at the domestic bit. All this plays out against some of the key historical events of the time: the Nixon–Kennedy race (Sterling Cooper is doing PR for Nixon), the crash of American Airlines Flight 1 in March 1962 (a character’s father is aboard, triggering a crisis of conscience as to whether he should capitalize on his family’s tragedy to help land the American Airlines account), and, inevitably, the Kennedy assassination, which ruins the wedding of a partner’s spoiled daughter.

As I have already mentioned, the actual stuff of Mad Men’s action is, essentially, the stuff of soap opera: abortions, secret pregnancies, extramarital affairs, office romances, and of course dire family secrets; what is supposed to give it its higher cultural resonance is the historical element. When people talk about the show, they talk (if they’re not talking about the clothes and furniture) about the special perspective its historical setting creates—the graphic picture that it is able to paint of the attitudes of an earlier time, attitudes likely to make us uncomfortable or outraged today. An unwanted pregnancy, after all, had different implications in 1960 than it does in 2011.

Advertisement

To my mind, the picture is too crude and the artist too pleased with himself. In Mad Men, everyone chain-smokes, every executive starts drinking before lunch, every man is a chauvinist pig, every male employee viciously competitive and jealous of his colleagues, every white person a reflexive racist (when not irritatingly patronizing). It’s not that you don’t know that, say, sexism was rampant in the workplace before the feminist movement; it’s just that, on the screen, the endless succession of leering junior execs and crude jokes and abusive behavior all meant to signal “sexism” doesn’t work—it’s wearying rather than illuminating.

Here, as with Don’s false identity and (literally) meretricious mother, Mad Men keeps telling you what to think instead of letting you think for yourself. As I watched the first season, the characters and their milieu were so unrelentingly repellent that I kept wondering whether the writers had been trying, unsuccessfully, for a kind of camp—for a tartly tongue-in-cheek send-up of Sixties attitudes. (I found myself wishing that the creators of Glee had gotten a stab at this material.) But the creators of Mad Men are in deadly earnest. It’s as if these forty- and thirty-somethings can’t quite believe how bad people were back then, and can’t resist the impulse to keep showing you.

This impulse might be worth indulging (briefly), but the problem with Mad Men is that it suffers from a hypocrisy of its own. As the camera glides over Joan’s gigantic bust and hourglass hips, as it languorously follows the swirls of cigarette smoke toward the ceiling, as the clinking of ice in the glass of someone’s midday Canadian Club is lovingly enhanced, you can’t help thinking that the creators of this show are indulging in a kind of dramatic having your cake and eating it, too: even as it invites us to be shocked by what it’s showing us (a scene people love to talk about is one in which a hugely pregnant Betty lights up a cigarette in a car), it keeps eroticizing what it’s showing us, too. For a drama (or book, or whatever) to invite an audience to feel superior to a less enlightened era even as it teases the regressive urges behind the behaviors associated with that era strikes me as the worst possible offense that can be committed in a creative work set in the past: it’s simultaneously contemptuous and pandering. Here, it cripples the show’s ability to tell us anything of real substance about the world it depicts.

Most of the show’s flaws can, in fact, be attributed to the way it waves certain flags in your face and leaves things at that, without serious thought about dramatic appropriateness or textured characterization. (The writers don’t really want you to think about what Betty might be thinking; they just want you to know that she’s one of those clueless 1960s mothers who smoked during pregnancy.) The writers like to trigger “issue”-related subplots by parachuting some new character or event into the action, often an element that has no relation to anything that’s come before. Although much has been made of the show’s treatment of race, the “treatment” is usually little more than a lazy allusion—race never really makes anything happen in the show. There’s a brief subplot at one point about one of the young associates, Paul Kinsey, a Princeton graduate who turns out—how or why, we never learn—to be living with a black supermarket checkout girl in Montclair, New Jersey. A few colleagues express surprise when they meet her at a party, we briefly see the couple heading to a protest march inMississippi, and that’s pretty much it—we never hear from or about her again.

Even more bizarrely, Lane Pryce, the buttoned-up British partner who’s been foisted on Sterling Cooper by its newly acquired parent company in London—you know he’s English because he wears waistcoats all the time and uses polysyllabic words a lot—is given a black Playboy bunny girlfriend whom he says he wants to marry, but she’s never explained and, apart from triggering a weird, vaguely sadomasochistic confrontation between Lane and his bigot father (who beats him with a cane and makes him say “Sir”), the affair leaves no trace. It’s just there, and we’re supposed to “get” what her presence is about, the way we’re supposed to “get” an advertisement in a magazine. The writing in Mad Men is, indeed, very much like the writing you find in ads—too many scenes feel like they have captions.

But then, why not have captions when so many scenes feel like cartoon panels? The show’s directorial style is static, airless. Scenes tend to be boxed: actors will be arranged within a frame—sitting in a car, at a desk, on a bed—and then they recite their lines, and that’s that. Characters seldom enter (or leave) the frame while already engaged in some activity, already talking about something—a useful technique (much used in shows like the old Law & Order) which strongly gives the textured sense of the characters’ reality, that they exist outside of the script.

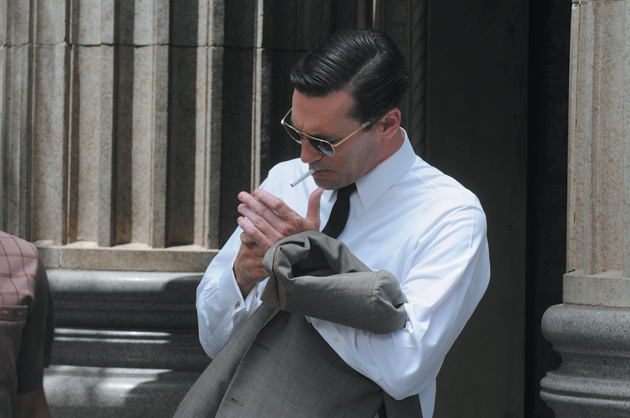

The acting itself is remarkably vacant, for the most part—none more so than the performance of Jon Hamm as Don. There is a long tradition of American actors who excel at suggesting the unconventional and sometimes unpleasant currents coursing beneath their appealing all-American looks: James Stewart was one, Matt Damon is another now. By contrast, you sometimes have the impression that Hamm was hired because he looks like the guy in the old Arrow Shirt ads: a foursquare, square-jawed fellow whose tormented interior we are constantly told about but never really feel. With rare exceptions (notably Robert Morse in an amusing cameo as the eccentric Japanophile partner Bert Cooper), the actors in this show are “acting the atmosphere,” as directors like to say: they’re playing “Sixties people,” rather than inhabiting this or that character, making him or her specific. A lot of Mad Men is like that.

The way that the scene about Lane and his black girlfriend somehow morphs into a scene about an unnatural emotional current between him and his father is typical of another common vice in Mad Men: you often feel that the writers are so pleased with this or that notion that they’ve forgotten the point they’re trying to make. During its first few seasons the show featured a closeted gay character—Sal Romano, the firm’s art director (he also wears vests). At the beginning of the show I thought there was going to be some story line that shed some interesting light on the repressive sexual mores of the time, but apart from a few semicomic suggestions that Sal’s wife is frustrated and that he’s attracted to one of his younger colleagues—and a moment when Don catches him making out with a bellhop when they’re both on a business trip, a revelation that, weirdly, had no repercussions—the little story line that Sal is finally given isn’t really about the closet at all. In the end, he is fired after rebuffing the advances of the firm’s most important client, a tobacco heir who consequently insists to the partners that Sal be fired. (Naturally he gives them a phony reason.) The partners, caving in to their big client, do as he says. But that’s not a story about gayness in the 1960s, about the closet; it’s a story about caving in to power, a story about business ethics.

To my mind, there are only two instances in which the writers of Mad Men have dramatized, rather than simply advertised, their chosen themes. One is about the curvy office manager Joan, who at one point is asked to help vet television scripts for potential conflicts of interest with clients’ ads, and finds she’s both good at it and intellectually stimulated by it—only to be told, in passing, that the firm has hired a man to do the job. The look on her face when she gets the news—first crushed, then resigned, because after all this is how it goes—is one of the moments of real poignancy in the show. It tells us far more about prefeminist America than all the dirty jokes and gropings the writers have inflicted on us thus far.

And there’s a marvelous sequence that comes at the climax of Season 4, in which Don’s secret past creates a real dramatic crisis in the Aristotelian sense: what Don has done, and what he does, and what he is and wants as opposed to what his society is and wants, all come together in a way that feels both inevitable and wrenching. At the beginning of the episode, we learn that Sterling Cooper’s biggest client—that tobacco company whose billings essentially keep it running—is about to drop the account; as a result, the agency is in serious danger. Then—luckily, as it would seem—a young executive seems on the verge of bringing in a huge account from North American Aviation, a defense contractor based in California. But the routine Defense Department background check that is mandated for companies doing business with NAA poses a threat to Don, who as we know was a deserter from the army.

This situation creates a conflict with an elegantly Sophoclean geometry: the survival of Don’s business depends on doing business with NAA, but doing business with NAA threatens Don himself—his personal survival. In the end, Don’s sometime rival—a younger colleague who discovered his secret long ago, but has kept it, sometimes grudgingly, and whom Don has bailed out at a crucial moment, too—covers for him, dumping NAA on some pretext.) As I watched this gripping episode I realized it was the only time that I had felt drawn into the drama as drama—that the writers had created a situation whose structure, rather than its accoutrements or “message,” was irresistible.

3.

In its glossy, semaphoric style, its tendency to invoke rather than unravel this or that issue, the way it uses a certain visual allure to blind rather than to enlighten, Mad Men is much like a successful advertisement itself. And yet as we know, the best ads tap into deep currents of emotion. As much as I disliked the show, I did find myself persisting. Why?

In the final episode of Season 1, there’s a terrific scene in which Don Draper is pitching a campaign for Kodak’s circular slide projector, which he has dubbed the “carousel”—a word, as he rightly intuits, that powerfully evokes childhood pleasures and, if you’re lucky, idyllic memories of family togetherness. To make his point, he’s stocked the projector he uses in the pitch with photos of his own family—which, as we know, is actually in the process of falling apart, due to his serial adulteries. But even as we know this, we can’t help submitting to the allure of the projected image of the strong, handsome man and his smiling and beautiful wife—the ideal, perhaps, that we all secretly carry of our own parents, whatever their lives and marriages may have been.

The tension between the luminous ideal and the unhappy reality is, of course, what the show thinks it’s “about”—reminding us, as it so often and so unsubtly does, that, like advertising itself, the decade it depicts was often hypocritical, indulging certain “images” and styles of behavior while knowing them to be false, even unjust. But this shallow aperçu can’t explain the profound emotionalism of the scene. In a lengthy New York Times article about Mad Men that appeared as the show—by then already a phenomenon—was going into its second season, its creator, Matthew Weiner, recalled that he had shown the carousel episode to his own parents, and the story he tells about that occasion suggests where the emotion may originate.

Weiner, it turns out—like his character, Don Draper—used his own family photographs to “stock” the scene: the most poignant image we see as Don clicks through the carousel of photos, a picture of Don and Betty smilingly sharing a hot dog (a casual intimacy that, we know, can now only be a memory), was based on an actual photograph of Weiner’s parents sharing a hot dog on their first date. Interestingly, Weiner made a point of telling the reporter who was interviewing him that when he showed the episode to his parents, they didn’t even remark on the borrowing—didn’t seem to make the connection.

The attentive and attention-hungry child, the heedless grownup: this pairing, I would argue, is a crucial one in Mad Men. The child’s-eye perspective is, in fact, one of the strongest and most original elements of the series as a whole. Children in Mad Men—not least, Don and Betty’s daughter, Sally—often have interesting and unexpected things to say. Perhaps the most interesting of the children is Glen, the odd little boy who lives down the street from the Drapers, whose mother is a divorcée shunned, at first, by the other couples on the block. Glen has a kind of fetishistic attachment to Betty—at one point, when she’s babysitting him, he asks for and receives a lock of her hair—and he occasionally pops up and has weirdly adult conversations with her. (“I’m so sad,” the housewife finds herself telling the nine-year-old as she sits in her station wagon in a supermarket parking lot. “I wish I were older,” he pointedly replies.) The loaded way in which Glen often simply stares at Betty and the other grownups suggested to me that he’s a kind of stand-in for Weiner, who had been a writer on The Sopranos and, more to the point, was born in 1965—and is, therefore, of an age with the children depicted on the show. That Glen is played by Weiner’s son strikingly hints at the very strong identification going on here.

It’s only when you realize that the most important “eye”—and “I”—in Mad Men belong to the watchful if often uncomprehending children, rather than to the badly behaved and often caricatured adults, that the show’s special appeal comes into focus. In the same Times article, Weiner tried to describe the impulses that lay at the core of his creation, acknowledging that

part of the show is trying to figure out—this sounds really ineloquent—trying to figure out what is the deal with my parents. Am I them? Because you know you are…. The truth is it’s such a trope to sit around and bash your parents. I don’t want it to be like that. They are my inspiration, let’s not pretend.

This, more than anything, explains why the greatest part of the audience for Mad Men is made up not, as you might have imagined at one point, by people of the generation it depicts—people who were in their twenties and thirties and forties in the 1960s, and are now in their sixties and seventies and eighties—but by viewers in their forties and early fifties today, which is to say of an age with those characters’ children. The point of identification is, in the end, not Don but Sally, not Betty but Glen: the watching, hopeful, and so often disillusioned children who would grow up to be this program’s audience, watching their younger selves watch their parents screw up.

Hence both the show’s serious failings and its strong appeal. If so much of Mad Men is curiously opaque, all inexplicable exteriors and posturing, it occurs to you that this is, after all, how the adult world often looks to children; whatever its blankness, that world, as recreated in the show, feels somehow real to those of us who were kids back then. As for the appeal: Who, after all, can resist the fantasy of seeing what your parents were like before you were born, or when you were still little—too little to understand what the deal was with them, something we can only do now, in hindsight? And who, after having that privileged view, would want to dismiss the lives they led and world they inhabited as trivial—as passing fads, moments of madness? Who would still want to bash them, instead of telling them that we know they were bad but that now we forgive them?

This Issue

February 24, 2011