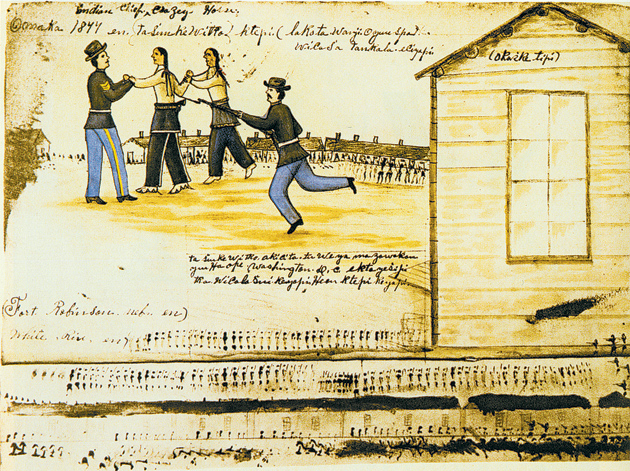

University of Cincinnati Libraries Digital Collections

Crazy Horse’s last moments, recorded by the Oglala artist Amos Bad Heart Bull. According to Thomas Powers in The Killing of Crazy Horse, ‘One fact was remembered with special clarity by almost every witness—Little Big Man’s effort to hold Crazy Horse as he struggled to escape, shown here in Bad Heart Bull’s drawing.’

In the 1990s, when I was on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in western South Dakota researching a book about its residents, the Oglala Sioux, people sometimes told me about sightings of the devil. A woman who had lived on Pine Ridge all her life told me that her friend had recently seen the devil walking in the evening on the Oelrichs road. He was wearing a suit and tie and looked like an ordinary man, she said, except for his thick, long tail. From the number of fatal car wrecks I knew of on the Oelrichs road I could almost believe the story. Sometimes on Pine Ridge—for example, when I came upon a burned-up car abandoned in the middle of a highway in a patch of still-wet asphalt that its flames had melted, or saw drunks staggering across the reservation border back to the beer-selling town of Whiteclay—a powerful sense of darkness shivered into my bones like ague.

The Killing of Crazy Horse by Thomas Powers examines the darkest episode ever to happen in that part of the world. In fact, I believe a lot of the darkness around there comes from that one killing—of the Oglala Chief Crazy Horse by the American army. Higher-ups in the army and the government regretted the killing but some said it was probably for the best. Nobody investigated it. People’s lives went on, and the Sioux, whom General Sherman had wanted to “reduce…to a helpless condition,” pretty much attained it. Crazy Horse receded from memory, except among his tribesmen and certain of their neighbors like John Neihardt and Mari Sandoz. And yet admirers kept thinking about Crazy Horse, and wondering exactly how and why he had died. Thomas Powers, a journalist whose past books have been about the national security apparatus and the CIA, now joins that number, with the most readable and detailed account of Crazy Horse’s death so far. It’s a passionate book without being in any way a sentimental one.

For both Indians and whites, Crazy Horse was magic. It’s hard even to describe how unique and brave and chivalrous and unpredictable and uncaught he was. When I was on Pine Ridge, a high school teacher of Lakota studies said of SuAnne Big Crow, a basketball star who had become a hero to the reservation, “She showed us a way to live on the earth.” For the Sioux resisting the army and the theft of treaty lands in the 1860s and 1870s, Crazy Horse did that. As an Oglala, he belonged to the largest of the seven tribes of the Teton, or western, Sioux, who lived in what’s now the Dakotas, Nebraska, Wyoming, and Montana. Today the western Sioux are more often called the Lakota.

Among the tribe’s many subcategories in the second half of the nineteenth century, an unofficial one became the most important: the northern Indians. These were the still-resisting Oglala and Hunkpapa and Miniconjou and other Sioux (along with some Cheyenne) who fought the whites, followed the surviving buffalo herds on the northern Plains, and stayed away from the transcontinental railroad and its band of settlement across mid-country. Crazy Horse and the Hunkpapa chief Sitting Bull rose to prominence among these “hostiles.” The army still considered northern Indians to be hostile even after they had quit fighting and come in to the Indian agencies (now known as reservations), where they joined the followers of Red Cloud and Spotted Tail, who had come in some years before.

Thinking about Crazy Horse’s magical qualities can be exhilarating, but a lot of darkness appears there, too. He was born in 1838 or maybe 1840, to an Oglala healer named Crazy Horse and his Miniconjou wife, Rattle Blanket Woman. She hanged herself when the boy, called Curly then because of his light hair, was about four. While still young, Curly distinguished himself in fights with other tribes. One of his first killings was of a Winnebago woman—an event his friends and contemporaries seem to have considered shameful. Through his young manhood, war honors piled up on him. For his bravery, his father gave him the name Crazy Horse, and took a new name for himself.

Crazy Horse always had supreme strategic sense and planned out every fight so he would win with the smallest loss to his own warriors. During a battle west of the Black Hills in 1866 he was among the decoys who lured a force of eighty-one cavalry and infantry into an ambush in which all the soldiers were wiped out. In about 1868 his tribe made him a Shirt Wearer, one of four outstanding men chosen as leaders. Soon after, he ran off with the wife of another man, who caught up with the two and shot Crazy Horse in the face. He survived, with a facial scar and powder marks that were often mentioned in later descriptions of him. Because of this scandal, tribal elders demoted him.

Advertisement

With 898 of his followers, Crazy Horse came into the Red Cloud Agency in May 1877 and declared he was done with war. You couldn’t really say he surrendered. The army never beat him; though shot at countless times, he’d never been hit. But in the spring of 1877 he accepted that fighting any longer was useless, and he let his fellow warriors and other Lakota persuade him to come in. Events leading to that moment were the Sioux victory in Red Cloud’s War, in 1868; the generous treaty the government made with the Sioux in 1870, which said they owned a large part of the present Dakotas, including the Black Hills; the annoying (to the Indians) entry of surveying parties into their lands; fights with surveying parties in 1872; the more annoying entry of a surveying and gold-seeking party led by General George Custer into the Black Hills in 1874; the discovery of gold by this party; the subsequent gold rush; the government’s attempt to buy the Black Hills, for not much; the armed resistance of the northern Indians to the sale; the military expeditions sent to crush the northern Indians in 1876; and the Indians’ defeat of General George Crook and, spectacularly, General Custer, leaders of two of these expeditions. Powers gives a masterful summary of Custer’s ignorance of the size of the Sioux forces and his disastrous deployment of troops.

Astonished by that second defeat, the US got serious, dispatched soldiers to harry the Indian camps in winter, sent agency Indians with gifts and persuasive arguments, and finally induced Crazy Horse and other hostiles to lay down arms. As Crazy Horse approaches the agency, ready for peace, darkness seeps all around. The music should be in the gloomiest of minor chords.

Many books have been written about the Indian wars on the Plains. There are probably millions of words about the Little Bighorn battle alone. To describe Crazy Horse’s end, Powers must include this big picture, of course; but parts of it he sketches in with just a line or two. He may have assumed that readers who pick up this book will already know something of the material. The angle he follows into the Crazy Horse story seems at first to be tangential: he says his original inspiration for the book came when he was reading the reminiscences of William Garnett, son of an Oglala woman and an army officer, who spoke Lakota and English and served as one of the interpreters at the Red Cloud Agency. With Garnett as a major source, Powers uses the interpreters for a connecting thread in the book’s beginning. This structural decision turns out to be inspired, however, because it lets him describe the shaky world of mutual confusion and deadly misunderstanding between white and Indian in which the interpreters lived, and in which Crazy Horse would find himself at the agency. Whenever important events occurred, the interpreters were there.

Powers’s other big structural decision is equally fruitful. Among the government officials in the story, he focuses on George Crook, the army general most involved with Crazy Horse’s fate in the last months of his life. Indeed, the book is almost more a character study of Crook than it is of Crazy Horse. The general emerges as the kind of hardworking, persistent, dogged, sensible person who is also basically an idiot. Wounded pride troubles him. His West Point classmate Phil Sheridan gets credit for things that Crook should’ve gotten credit for in the Civil War. Newspaper correspondents misrepresent him. Crook doesn’t talk much, and makes his predictable decisions on his own. Other books about these events and times concentrate on the glamorous General Custer, naturally—but in a book about Crazy Horse, that can be a red herring. Custer gave Crazy Horse reason to fight, and by dying at Little Bighorn made him permanently famous (and vice versa). But Crazy Horse’s real, dull, grinding, ultimately fatal nemesis was Crook.

If Crazy Horse had magic, Crook had whatever the opposite of magic is. He suffered from bum luck, down to his name, too apt for a general involved in the theft of the Hills. And yet Crook tried hard and endured much, and when there was fighting he was there with his soldiers. In a skirmish with Pitt River Indians in California an arrow hit him in the thigh, and he carried the point in him the rest of his life. Against the Apache in Arizona he used other Apache as trackers and fighters, with success. Chiefs who proved recalcitrant he had no hesitation to hang. But at the Battle of the Rosebud, where Crazy Horse and other northern Indians turned back his expedition against them in June 1876, Crook extended his lines unwisely and came close to being wiped out. In one encounter (as Crook later told an army scout), he fired at Crazy Horse more than twenty times with no effect. Powers remarks:

Advertisement

With a man like Crook the first shot would have been a casual try of luck; the twentieth would have been grimly determined, with teeth clenched, hands steadied by murderous will.

In early dealings with Crazy Horse, when the chief was considering coming in and just before, Crook made blunders that had serious consequences. Perhaps driven by a sense of competition with General Nelson Miles, another officer with a force on the Plains, who was also trying to effect a surrender, Crook promised Crazy Horse he would help him establish his own agency in the north, on Beaver Creek near the Black Hills. Crook also said that Crazy Horse and his people would be allowed to go back north for a summer buffalo hunt after they reported to the Red Cloud Agency. Crook could by no means guarantee either of these assurances, and when he didn’t make good on them, Crazy Horse’s unmet expectations erased any trust between them.

Even worse was Crook’s enthusiasm for Lieutenant William Philo Clark, his main adviser and representative in the army’s dealings with Crazy Horse. Clark did know a lot about Indians—his book, The Indian Sign Language, is still in print—but all his expertise was, to Clark, merely a means of manipulation. He prided himself on what he called his ability to “work” Indians. In the end, Clark’s bad faith, arrogance, and bluster knocked to pieces all chance of reaching an understanding with Crazy Horse and his followers. One did not “work” Crazy Horse.

Like William Garnett, Baptiste “Big Bat” Pourier, Louis Bordeaux, and the other interpreters whose points of view frame the story, Powers can see things from both the white and Indian sides. To take one example, his account of the warriors’ invocation of the spirit world with the medicine objects they brought into battle is both sympathetic and thorough. Before turning to the Battle of the Rosebud, he spends five pages describing the war charms and paint important to Crazy Horse and others (golden eagle feathers tied in the war pony’s tail, the small “spirit rocks” Crazy Horse wore under his left arm and behind his left ear, dried wild aster seeds mixed with dried eagle heart and brains, etc.). At the end of this catalog, Powers says:

That is what rode south toward the Rosebud on the night of June 16–17, 1876: thunder dreamers, storm splitters, men who could turn aside bullets, men on horses that flew like hawks or darted like dragonflies. They came with power as real as a whirlwind, as if the whole natural world—the bears and the buffalo, the storm clouds and the lightning—were moving in tandem with the Indians, protecting them and making them strong.

Powers switches back to the soldiers’ perspective when he begins the part about Crazy Horse’s “surrender.” The Red Cloud Agency, where Crazy Horse and his band enrolled, took its name from the Oglala chief who presided there, and who would make his own malign contribution to Crazy Horse’s demise. Lieutenant Clark got to know Red Cloud through long conversations in sign language. Of Red Cloud’s style of sign talking, Powers says:

Most signers made use of a generous circle of space, moving their hands emphatically within a circle thirty inches in diameter. But Red Cloud was restrained; his gestures were tight and small in a circle no more than a foot across.

(The source for this is another army student of Indian sign language, Lieutenant Hugh Scott.)

Somehow that one detail makes Red Cloud more vivid than any other I’ve read about him. Red Cloud, an awesome warrior in his day, was a big man—Crazy Horse, by contrast, was slight—and that compact style of signing contains Red Cloud’s character during his life at the agency: subtle, held in, calculating, careful; a wicked whisperer. Once Crazy Horse entered Red Cloud’s realm of influence, darkness began blooming all around. Certain accounts of Crazy Horse’s end cast Red Cloud as the main villain, and a 1996 made-for-TV movie about Crazy Horse portrayed Red Cloud so negatively that the chief’s descendants threatened to sue. But Powers does not oversimplify, or need to. At the agency all kinds of people, even longtime friends, schemed against Crazy Horse’s well-being and even his life. From the view of history, the turmoil is not surprising—what the Lakota were going through in those early reservation days, after the sudden loss of their nomadic life, amounted to a surrender, a revolution, and an ad-hoc constitutional convention, all rolled into one.

During this phase the only actor in the drama whom Powers perhaps goes a bit easy on is Crazy Horse himself. For a clearer sense of Crazy Horse’s strangeness and his sometimes difficult relations with his own tribe, Kingsley M. Bray’s definitive 2006 biography, Crazy Horse: A Lakota Life, fills in some gaps. Bray describes at length the instances during the winter of 1877, after the Bighorn battle, when Crazy Horse killed the ponies of tribesmen who wanted to quit being at war and leave for the agencies. In some cases Crazy Horse said he would kill the deserters themselves. The Cheyenne chief Little Wolf, after Crazy Horse’s men shot some of his people’s ponies, left anyway, promising to get vengeance on Crazy Horse. A stronger sense of this background makes the hatred that Crazy Horse aroused among many at the agency seem more understandable.

Once he had settled at Red Cloud, the formerly elusive warrior was big news—everybody wanted to see the man who had defeated Custer. Reporters and other whites made a fuss over him, inflaming Sioux jealousy, never a difficult thing to do. Lieutenant Clark cultivated him, creepily; Clark may even have engineered Crazy Horse’s taking of a new wife, Nellie Larrabee, a young part-Sioux daughter of an agency trader, who moved in with Crazy Horse and his first wife, Black Shawl Woman, thus angering the girl’s family and a man named Sioux Bob, her sometime companion. Crook and others in the government wanted Crazy Horse to go to Washington for a meeting with the president; Crazy Horse said he’d go, but only after he had been given his agency on Beaver Creek. Told he must first talk with the “Great Father,” Crazy Horse replied, sensibly, that he already had his father right there with him. Indeed, Crazy Horse’s father and stepmother had almost always traveled with him, and were still camped nearby. He kept asking when he could leave on the promised buffalo hunt, and kept getting the run-around.

Having surrendered his guns and horses, the chief, who had been the army’s enemy just a few months before, was now made an army scout—Clark’s doing—and given a horse, a pistol, and an army carbine. Having sworn never to go to war again, he was now asked to help the army fight the Nez Perce, who had just escaped their reservation and were heading across Montana bound for Canada. In a council Clark held with Crazy Horse about this, anger exploded, a shifty interpreter said Crazy Horse planned to go on the warpath, Clark got his back up, and his self-serving goodwill toward the chief evaporated. From then on, Indian enmity, with Red Cloud at its center, combined with the removal of Clark’s protection, doomed Crazy Horse. The problem with Clark seems to have been one of dominance. Clark wanted submissive behavior from the chief, and Crazy Horse, who had not been beaten in battle, couldn’t pretend. His announcing, contemptuously, that he would go and fight the white men’s enemies if they could not do it themselves seems to have finished him with Clark.

Now darkness was everywhere. Red Cloud had helped it along by informing the authorities, untruthfully, that Crazy Horse would kill whites if allowed to go on the buffalo hunt. Because of the rising alarm, Crook received an order from his superior, General Sheridan, to look into the Crazy Horse situation. Arrived at Camp Robinson, the army post near the agency, Crook was on his way to a last-chance parley with Crazy Horse when an Indian dispatched by unknown persons, probably including Red Cloud, told Crook that Crazy Horse planned to kill him at the council.

Crook pondered, then decided to turn around. The decision was one of the regrets he would carry for the rest of his life. Here, Powers’s focus on Crook adds an important new piece to the story. When fighting the Apache, Crook had been in a nearly identical situation. Warned in advance, Crook went to the council anyway, where the Apache did in fact try to kill him. Powers compares Crook, as a result of this incident, to “a man who has once stepped over a log onto a rattlesnake. He will think twice about every log for the rest of his life.”

Crazy Horse was not even at the council. Had Crook not made the decision he did, but attended the council anyway, he might have gotten an inkling of the combination arrayed against the chief. Instead, the Crazy Horse problem now passed the talking stage. Crook and Clark met secretly with scouts and other Indians opposed to Crazy Horse and made plans to kill him that night. Crook then left for the railroad. News of the plan quickly got back to Crazy Horse, who gave his guns to a follower and spent the night waiting in his tipi armed only with a knife—surely one of the loneliest vigils in our history. Black Shawl Woman was still with him (the new wife had departed sometime before), and for bravery in extremis you have to hand it to Black Shawl Woman, too.

The endgame proceeded. The plan to kill Crazy Horse was countermanded, replaced by an order to arrest him at dawn. Sheridan intended to have him sent east on the railroad, to be imprisoned in Fort Marion, Florida. A small army of scouts rode to Crazy Horse’s camp in the morning, but he had ridden off for the Spotted Tail Agency, about thirty miles away, with Black Shawl Woman and two followers. At Spotted Tail, the agent, Lieutenant Jesse Lee, knew of the arrest order. Lee talked to Crazy Horse, who was now in a terrible mental state, and persuaded him to go back. He left Black Shawl Woman with her parents at Spotted Tail.

After a night of being watched, Crazy Horse set out for Red Cloud with Lee and a guard of Indian scouts. Lee told him he could make his case to the post commander when they arrived, but of course he couldn’t—orders were orders. At Camp Robinson, the post near the agency, while resisting being put in the jail, Crazy Horse was bayonetted twice in the back. He died on the floor of the adjutant’s office later that night.

Neither Crook, nor Clark, nor the post commander was there when Crazy Horse was stabbed. On his last day, only Crazy Horse showed bravery. At Spotted Tail, when he had expressed to Lee his well-founded doubts about returning to Red Cloud, Lee told him that he was no coward, and could “face the music” there. “‘This remark seemed to appeal to him and he said he would go,'” Lee recalled. Crazy Horse had promised peace and did not turn aside. Had he wished, he could have incited a lot of bloodshed, maybe a new Indian war. Alone and terrified, he behaved honorably.

The Killing of Crazy Horse brings out details I’ve run across nowhere else. I’m sure it’s unhealthy for the soul to take satisfaction in the fact that Captain James Kennington, the officer of the day in charge of putting Crazy Horse in the jail, who was heard shouting “Stab the sonofabitch!” during the struggle, suffered from testicular pain for the rest of his life. Its cause was a fall onto his saddle horn when his horse went down on the way to the Battle of Slim Buttes in September 1876; Powers found this information in retirement board proceedings in Kennington’s personal file. Also, I had read elsewhere of the misery of the Sioux’s Cheyenne allies when they were attacked by the army in the winter campaign of 1877. But I’d never read that, as Powers reveals, the army’s Shoshone scouts began howling with rage and grief when they discovered, among the Cheyenne’s effects, a bag containing the right hands of a dozen Shoshone children killed by the Cheyenne on a recent raid. Though the arrival of white people increased the darkness, Powers shows it existed before. As an old woman at Pine Ridge told a Yale anthropologist in 1931, she would like to go back to the days before the reservation, “if we could be free from attack by the enemy.”

Powers sees Crazy Horse as a man “looking for death” in the last months of his life. He quotes the famous valedictory pronounced beside the body by Crazy Horse’s friend Touch the Clouds: “It is good. He has looked for death, and it has come.” Perhaps the chief did want to get out of this world, and—who knows?—remembered the path taken by his mother when he was small. A simpler explanation may be that he was in way over his head at the agency. He had always lived free on the Plains, he knew little about the white world, he had no idea how famous he was, he couldn’t grasp the forces around him. He was nothing like an interpreter. Powers does not quote the remark of the shifty interpreter Frank Grouard, who saw the chief being led to the guardhouse and realized that “he did not know that he was to be placed in confinement.” Crazy Horse did not even know what a jail was.

Had Crazy Horse gone to Washington when asked to, he probably would not have been killed. But then he would not have been Crazy Horse. Had he gone, he would have been photographed, and gawked at, and reduced to the level of a celebrity. No photo of him exists today. The speeches he made were brief and few. He occupies a huge, mysterious region in our imaginations, and the power of that causes people to carve mountains in his supposed likeness and write passionately about him. Powers ends his book by saying, of a vanished medicine bundle believed to have been Crazy Horse’s, that it “marks a divide between the things that have been lost and the things that survive.” The book shows that in the shadow region between the known and the never-to-be-known, Crazy Horse himself defiantly survives.

This Issue

February 24, 2011