On July 16, 2009, Sergeant James Crowley, a white police officer answering a call to investigate a possible break-in at a Cambridge, Massachusetts, address not far from Harvard, arrested Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr., charging him with disorderly conduct, even though the middle-aged black man had shown that he was not a burglar and was not trespassing in his own home. The district attorney dismissed the charge five days later. Yet the controversy over the arrest of one of Harvard’s most famous professors set off debates about police conduct and racial profiling and also about race, class, and privilege. Because, as it turned out, black people and white people viewed these matters from such different perspectives, the arrest of Professor Gates reminded many that a profound racial divide still exists, in spite of our having elected a black president.

A week later, at a news conference about health care, President Obama was asked about the incident and he said that Skip Gates was a friend and that the Cambridge police had “acted stupidly” in arresting somebody who had proven that he was in his own home. The uproar that followed led Obama to invite both Gates and Crowley to the White House for guy talk and trouser hitching as they drank beer. Obama seemed to be scrambling to defend his image as the national reconciler, while having to absorb the warning implicit in the protests of policemen’s unions that white America was made uneasy by the nation’s first black president speaking as a black man or identifying with the black man’s point of view.

In The Presumption of Guilt, Charles Ogletree regrets that Obama lost what has come to be called a “teachable moment,” a chance to educate the country, Philadelphia speech–style, about race, yet had to pay a political cost for his innocent part in the Gates affair nevertheless. Ogletree argues that what was in effect the silencing of President Obama on the issue of how blacks are targeted by police helped to embolden Glenn Beck and the Tea Party movement at a critical moment. Ogletree may be right, and The Presumption of Guilt is intended to impart some of the lessons about the injustice of racial profiling that Obama did not—and may never—get a chance to draw. But Ogletree has his own innocence about integration as a form of social protection for blacks, and a perhaps inadvertent message of his book is that middle-class black people, or black people connected to powerful institutions, should not expect to be exempt from the systemic racism that affects black American lives.

Ogletree is Gates’s personal attorney as well as a member of the Harvard Law School faculty where he served as “mentor” to both the President and the First Lady. He loses no time in affirming the legal correctness of the black man’s point of view in Gates’s situation. That July morning in 2009 an elderly white woman told another white woman that she saw two men who looked as though they were trying to force the door at a house on Ware Street, and the other woman phoned the police. What the woman saw was Gates, whose key was not working, forcing open his jammed front door with the help of his driver. The woman who made the call to 911 also said that it was possible that a crime had not been committed, that the two men maybe had had a problem with their key.

Sergeant Crowley then arrived on the scene. Gates was on the phone inside his rented house, reporting his faulty door to Harvard housing. Ogletree is clear that no matter how disrespectful and “uncooperative” Professor Gates may have been, he was within his rights. The statute concerning disorderly conduct that Crowley invoked to make the arrest did not apply, because Gates’s behavior was not likely to affect other members of the public. But that was also why Crowley insisted that Gates come outside. Then, too, Ogletree writes, he had no right to step inside Gates’s home unasked, but he did. Gates was not obliged to say who he was, produce ID, or step outside with the officer, but he did. If the arrest was “not inevitable,” as Ogletree phrases it, then what was Sergeant Crowley’s “motivation” for putting Professor Gates in handcuffs?

Ogletree compared the arresting officers’ statements with the police dispatch log and found that at no time did the woman who called the police say the men were African-American. One of the two witnesses said one man may have been Hispanic. “To this date, the only person ever to suggest that two African Americans with backpacks were involved is Officer 52 in this transcription, who is identified as Sgt. James Crowley.”

Advertisement

The transcript also indicates that when Professor Gates produced his ID he told Crowley to phone the chief of the Harvard University police department. Instead, Crowley told the Cambridge police dispatcher to “keep the cars coming,” and to send the campus police, too. His report, Ogletree writes, “reflects his skepticism about Professor Gates’s actual identity.” Having been shown Gates’s information, he acted as though he was dealing with a suspicious person. He didn’t, couldn’t, or wouldn’t believe that Gates was who he said he was.

The six-minute clash between Crowley and Gates, Ogletree says, tells the story of a police officer who believes, “perhaps because of his prejudices, that a crime is being committed and an innocent person [who] believes that he is being unfairly profiled by a police officer.” However, for Ogletree the deeper story, as Crowley’s report indicates, is that Crowley arrested Gates because “he had been called names of a racial nature by Professor Gates.” The black man was busted for the crime black people sometimes call “contempt of cop.”

It is maybe a reflection of what the post–September 11 atmosphere of humorless security officials in public places has further done to us as a society that so many people seemed to accept that in a contest between freedom of speech and the authority of the law it was to be expected that the representative of authority would win. If civilian Gates gave uniformed Crowley “attitude,” then, in this view, he was asking for trouble. Two black colleagues of Crowley’s sided with him. But it is not a crime to sound off to uniforms. Some white people also said that they believed Crowley would have treated a white man screaming at him no differently. They had trouble grasping the point that not only would Crowley not have looked at an angry white man in the same way, a white person in his home would not have looked at Crowley as Gates did.

The histories are entirely different. Gates insulted the blue-collar Crowley, who could immediately punish the offense of having been verbally lectured by a well-off black man, because he assumed that he was working in a society that tolerates racial profiling as a crime-fighting strategy. White policemen probably humiliate black men somewhere in America every day.

What did not receive much attention compared to his criticism of the Cambridge police was the President’s mention of the racial-profiling bill that he worked on in the Illinois state legislature, “because there was indisputable evidence that blacks and Hispanics were being stopped disproportionately.” Gates’s arrest, Ogletree goes on to say, had to be seen in the context of “law enforcement prone to be biased against African Americans” and blacks mistrustful and fearful of law enforcement.

Ogletree reviews the 1991 Rodney King beating and some of the most notorious police misconduct cases since—Abner Louima, the Haitian immigrant tortured by New York City police in 1997; four young black men shot (three of whom were injured) on the New Jersey Turnpike in 1998 when police, without any clear evidence, suspected them of being involved in gang activities; Amadou Diallo, the Guinean immigrant shot in New York in 1999 nineteen times by police who were acquitted of all charges; Sean Bell, unarmed in a stopped car, killed on the eve of his wedding in Queens in 2008 in a hail of police bullets. The officers were acquitted of all charges. These sensational miscarriages were brewed in the culture of racial profiling.

The Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Statistics found in 2007, according to Roy L. Brooks in his Racial Justice in the Age of Obama (2009), that while drivers of all colors were pulled over by police at approximately the same rate, black and Latino drivers were much more likely to be searched and arrested. Blacks were twice as likely to be arrested as whites and they were also more likely to be released from jail without a charge having been made, which, Brooks contends, “strongly suggests that there was no probable cause for arresting them in the first place.”

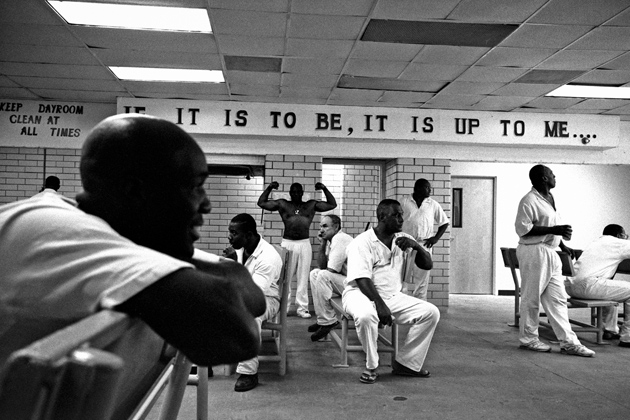

Moreover, black America for the most part lives in areas under heavy police surveillance. Acquaintance with the state as a disciplinary force comes early. According to statistics from the Pew Center as well as the Department of Justice that Ogletree cites, the “realities of racial disparity in the criminal justice system” are that “‘one in every 15 black males aged 18 or older is in prison or jail,’ versus one in every 36 men for Hispanic males and one in every 106 White males,” and that “the lifetime risk of incarceration for a child born in 2001 is 1 in 3 for black males, 1 in 6 for Latino males, and 1 in 17 for white males.”

Advertisement

Ogletree is knowledgeable about the insidiousness of institutional racism,1 but it is unfortunate that he has chosen to examine the practice of racial profiling by turning his book into a collection of statements by one hundred prominent victims of contemptuous treatment by authorities. They include lawyers, professors, journalists, athletes, and actors—Eric Holder, Vernon Jordan, Blair Underwood, Calvin Butts, William Julius Wilson, Joe Morgan, Roger Wilkins, Derrick Bell, and Spike Lee—though not everyone in Ogletree’s roster of the injured is known nationally. Some have found themselves over the hoods of cars, mistaken for criminals, treated like criminals. Cops are suspicious of interracial couples and of black guys they consider to be in the wrong neighborhood. Black men are stopped, searched, detained, threatened.

Most of the incidents Ogletree has heard about from his list of successful black men are confrontations with police that could have escalated. For instance, in the early 1980s L.A. police ordered Johnnie Cochran out of his Rolls-Royce at gunpoint while his children watched in horror. Ogletree’s definition of racial profiling is broad. He includes Lou Gossett Jr. saying that his refusal to accept certain film roles because of his pride as a black man meant that he was denied other parts as punishment.

In this collection of anecdotes, racial profiling is taken to be any manifestation of racist assumptions, such as white women clutching their handbags when black men approach them on the streets. The black men in Ogletree’s survey remember insults from hotel doormen and valets. New York Times columnist Bob Herbert recollects that a taxi driver once refused to take him to his office, a story almost every black man in New York City could tell. The insults Ogletree records are not trivial; but one quickly understands the irritation of the black working poor with the outrage of black professionals at the social indignities they encounter. There are worse things than not having one’s high social status acknowledged by whites.

Maybe the point is that no black person should have to stomach any bigotry, but the resentment Ogletree’s men—a number of them Harvard graduates—express at having been taken for a servant or menial by whites could make one wonder if their parents ever told them that they themselves ought not to judge a black man by the work he was able to find. That racism can make race trump class and cancel out individual accomplishment has long been a theme of black literature, a sort of group truth that gets restated with each generation. Hip-hop’s cynicism helped young black men to get over any cultural ambivalence about material ambitions that the militant black generation of the 1960s had denounced.

In fact, success itself became a form of militancy: the last place that “they” want “us” is in the boardroom, so get there or form your own Wu Tang Clan. But in the confrontations with police described in Ogletree’s book, the black man is, in effect, being told that his success, his being a part of the system, doesn’t purchase what it gets a white man: protection of the law. He is reduced to a stereotype, reminded of his group’s impotence, thrown back into history, placed in the white man’s power.

Ogletree is saying that Gates’s case is not some freak event. However, by concentrating only on successful black men, Ogletree isolates them as a class from the rest of black America and the larger setting he asks us to keep in mind; as a result he somewhat misspends his own “teachable moment.” For a cogent history of racial profiling and its social consequences, one can turn to a study such as David A. Harris’s admirable Profiles in Injustice: Why Racial Profiling Cannot Work (2002).

Harris explains that racial profiling came from criminal profiling, a police technique whereby a set of characteristics associated with a certain crime are used to identify the type of person likely to commit it. For example, in 1969, when thirty-three of forty attempts to hijack US planes were successful, federal authorities reasoned that hijackers had to be stopped on the ground and they developed a hijackers’ profile to be used in screening passengers. But it didn’t work, as Harris dryly notes, and in 1973 the FAA adopted mandatory electronic screening of all passengers.

Nevertheless, in the early 1980s, Harris relates, federal agents believed they could predict which air passengers might carry drugs and in 1989, in US v. Sokolow, the Supreme Court upheld the use of profiles in the detention of drug-trafficking suspects at airports. By that time a Florida state trooper had made a national reputation from the number of major narcotics arrests he chalked up on his stretch of highway. He is credited with being the first to apply profiling to “everyday citizens in their cars.” From the arrests, the trooper identified what he called “cumulative similarities” that could make him regard a driver as suspicious and worth a closer look. He got around legal objections to his operating on mere hunches by claiming that he first stopped the suspects for traffic violations and the “cumulative similarities” came into play afterward.

Harris says that the DEA enthusiastically took up the trooper’s method, and in its training videos, suspects were black or had Hispanic last names. Early on, the Supreme Court tended to support “high-discretion police tactics” in pedestrian stop-and-frisk cases as well. Harris points out that blacks are not the only targets of racial profiling: the police also focus on Latinos, Asians, and Arabs, depending on the type of crime that police associate with these groups and their neighborhoods. There have been legislative and judicial attempts to curb the use of racial profiling as more and more data reveal that it is ineffective in stopping crime. Racial profiling, Harris argues, puts the legitimacy of the entire justice system at risk.

Some conservative writers contend that the legal system is race-neutral for the most part and that the high number of blacks in prisons confirms the harsh reality that blacks tend to commit the violent crimes for which people are put behind bars, just as illegal weapons possession and drug trafficking are offenses associated with inner cities, which means the police have due cause to use racial profiling. However, the contributors to Whitewashing Race: The Myth of a Color-Blind Society (2003), an exhaustive analysis of the continued significance of race, counter that the research that such conservatives rely on is out of date, and that more valid and recent studies show that, since the 1990s, “paramilitary responses” by SWAT teams and other heavily armed police units “to gangs and drugs in the cities” have only intensified the use of stereotypical conceptions of race in order to prosecute offenses.

To concentrate on the sources of crime, and society’s responsibility for them, is now often dismissed as an irrelevant, old-fashioned liberal approach to a thorny social question, just as explorations of deep-rooted “disadvantages” in black life, the part that the legacy of racism plays in invisible discrimination today, are viewed by some whites as the continued special pleading of blacks. We are far from Ramsey Clark’s Crime in America (1970) in which he argued that the crimes of the poor enraged and frightened the more comfortable majority of Americans because riots, robbery, and rape were so foreign to the experience of middle-class people that such crimes were incomprehensible. Clark argued that the poor would not resort to these crimes if their opportunities had been better and more genuine. In this view, the irrational conditions that the poor had to cope with were among the causes of violent offenses. By the time of the Reagan reaction, however, Clark’s respect for black rage was no longer acceptable to most white voters as a reasonable approach to policy.

Moreover, the image of black youth in the media had changed. Where black students had been a symbol of good in the civil rights movement, once black militants repudiated nonviolence, the popular image of black youth darkened. By the 1980s, young black males were depicted as urban marauders, and many did in fact prey on the weakest in the ghetto. Even Rosa Parks got mugged in Detroit (her neighbors found the culprits and subjected them to harsh punishment, but others had no such protectors).

Around this time black youths in cities across the country were entering the underground economy of the cocaine trade in troubling numbers as they failed to secure meaningful employment in the mainstream world. The first Bush administration inaugurated the Violence Initiative, a series of studies that sought to determine whether black youth were prone to violence because of behavioral or biological factors. In 1994 the Clinton administration passed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, which extended the death penalty, approved a billion-dollar budget for new prisons, ended higher education programs in prisons, called for juveniles to be tried as adults in certain cases, and made life imprisonment mandatory after three or more federal convictions for violent felonies or drug-trafficking crimes.

Bakari Kitwana, executive editor of The Source, a rap music magazine, observes in The Hip Hop Generation (2002) that gang culture evolved along with the war on drugs almost as a business enterprise. By 1998, Kitwana notes, federal authorities judged that gang activity took place in every state, in both urban and rural locations. Local measures against gangs, he contends, became anti-youth laws. In 1992, Chicago had an ordinance in place that prohibited two or more young people from gathering in public places. Law enforcement agencies in Chicago, Houston, and Los Angeles developed databases from gang profiles. Kitwana claimed that the Los Angeles sheriff’s department database held at least 140,000 names, including those of black and Latino youth who did no more than dress in the hip-hop manner or were into grafitti. Kitwana makes the point that white people constitute the great proportion of the nation’s drug users and white youth buy more rap music than black youth.

The literature on race and the criminal justice system is extensive2; the film documentaries about the problem tell us things we need to know; the jails keep filling with black and brown people. Now and then a book comes along that might in time touch the public and educate social commentators, policymakers, and politicians about a glaring wrong that we have been living with that we also somehow don’t know how to face. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness by Michelle Alexander is such a work. A former director of the Racial Justice Project at the Northern California ACLU, now a professor at the Ohio State University law school, Alexander considers the evidence and concludes that our prison system is a unique form of social control, much like slavery and Jim Crow, the systems it has replaced.

Alexander is not the first to offer this bitter analysis, but The New Jim Crow is striking in the intelligence of her ideas, her powers of summary, and the force of her writing. Her tone is disarming throughout; she speaks as a concerned citizen, not as an expert, though she is one. She can make the abstract concrete, as J. Saunders Redding once said in praise of W.E.B. Du Bois, and Alexander deserves to be compared to Du Bois in her ability to distill and lay out as mighty human drama a complex argument and history.

“Laws prohibiting the use and sale of drugs are facially race neutral,” she writes, “but they are enforced in a highly discriminatory fashion.” To cite just one example of such discrimination, whites who use powder cocaine are often dealt with mildly. Blacks who use crack cocaine are often subject to many years in prison:

The decision to wage the drug war primarily in black and brown communities rather than white ones and to target African Americans but not whites on freeways and train stations has had precisely the same effect as the literacy and poll taxes of an earlier era. A facially race-neutral system of laws has operated to create a racial caste system.

Alexander argues that racial profiling is a gateway into this system of “racial stigmatization and permanent marginalization.” To have been in prison excludes many people of color permanently from the mainstream economy, because former prisoners are trapped in an “underworld of legalized discrimination.” The “racial isolation” of the ghetto poor makes them vulnerable in the futile war on drugs. Alexander cites a 2002 study conducted in Seattle that found that the police ignored the open-air activities of white drug dealers and went after black crack dealers in one area instead.

Even though Seattle’s drug war tactics might be in violation of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, the Supreme Court has made it nearly impossible to challenge race discrimination in the criminal justice system. “The barriers” to effective lawsuits are so high, Alexander writes, that few “are even filed, notwithstanding shocking and indefensible racial disparities.”

The Supreme Court, Alexander asserts, has given the police license to discriminate. Police officers then find it easy to claim that race was not the only factor in a stop and search. A study conducted in New Jersey exposed the absurdity of racial profiling: “Although whites were more likely to be guilty of carrying drugs, they were far less likely to be viewed as suspicious.” Alexander notes that in the beginning police and prosecutors did not want the war on drugs. But it soon became clear that the financial incentives were too great to ignore. Consequently, the civil rights movement’s strategies for racial justice are inadequate, Alexander says. Affirmative action cannot help those at the bottom. Black people must seek new allies and address the mass incarceration of blacks as a human rights issue.

Blacks, Alexander shows, have made up a disproportionate amount of the prison population since the US first had jails, and race has always influenced the administration of justice in America. The police have always been biased and every drug war in the country’s history has been aimed at minorities. The tactics of mass incarceration are not new or original, but the war on drugs has given rise to a system that governs “entire communities of color.” In the ghetto, Alexander continues, everyone is either directly or indirectly subjected to the new caste system that has emerged. She is most eloquent when describing the psychological effects on individuals, families, and neighborhoods of the shame and humiliation of prison:

The nature of the criminal justice system has changed. It is no longer concerned primarily with the prevention and punishment of crime, but rather with the management and control of the dispossessed.

Alexander does not believe that the development of this system and the election of Obama are contradictory. We are not a country that would tolerate its prison population being 100 percent black. We will accept its being 90 percent black. C. Vann Woodward wrote The Strange Career of Jim Crow (1955) as the civil rights movement was challenging segregation. Looking back, his optimism and relief at the crumbling of the old order are heartbreaking.

This Issue

March 10, 2011

Marilyn

The Bobby Fischer Defense

How We Know

-

1

See Olgetree’s All Deliberate Speed: Reflections on the First Half-Century of Brown v. Board of Education (Norton, 2004) and his contributions to Beyond the Rodney King Story: An Investigation of Police Conduct in Minority Communities (Northeastern University Press, 1995). ↩

-

2

See for example Angela Davis’s excellent Are Prisons Obsolete? (Seven Stories Press, 2003). ↩