In a totalitarian regime, you never know the mistakes that are made. But in a democracy, if anybody does something wrong, against the will of the people, it will float to the surface. The whole people are looking.

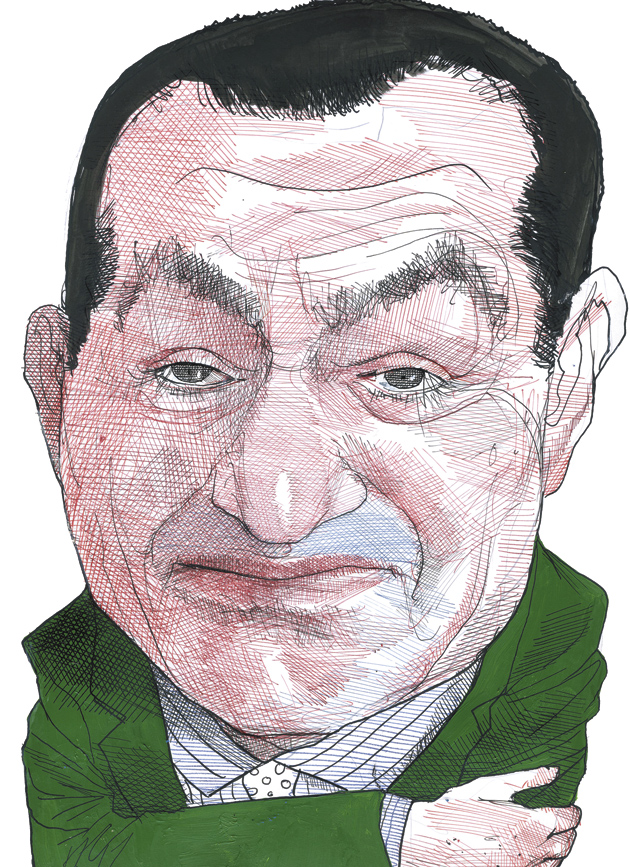

—Hosni Mubarak in an interview from Sandcastles: The Arabs in Search of the Modern World by Milton Viorst (Knopf, 1994)

Late last March Muammar Qaddafi, whose official title is Brother Leader of the Great Libyan Arab People’s Jamahiriya, hosted a summit meeting of Arab heads of state. Leaders of the twenty-two Arab League member countries had gathered dozens of times since the first such meeting in 1964, but never before in Libya. Given Qaddafi’s penchant for rambling incoherence and his regime’s reputation for shambolic management, delegates rather dreaded the event, particularly since it was to be held not in the Libyan capital, Tripoli, but in Qaddafi’s bleak little hometown of Sirte, three hundred kilometers away.

Yet the summit passed without a hitch. Qaddafi kept his speech tactfully short. The food, provided by a Turkish caterer, was ample and edible. As for the summit’s outcome, it was much as always. The final declaration blasted Israel, swore to liberate Jerusalem, and spoke of the urgency of Arab unity. Slightly more in the spirit of the age, it alluded to enhancing youth participation in society and called for adopting an initiative by the Tunisian president, Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, to declare 2010 the Year of Youth. The leaders also stressed the need to

establish the culture of openness and the acceptance of the other, and to support the principles of fraternity, tolerance, and respect of human values that emphasize human rights, respect human dignity, and protect human freedom.

In short, the usual fluff.

One thing that did prove jarring was the music. At every pause in the speech-making throughout the two-day event, a single strident martial tune blared ceaselessly at full volume from every loudspeaker throughout the gleaming marble-and-glass conference center, the rousing violin chords of the finale fading directly into its opening trumpet blasts in an endless, maddening loop. This was “Burkan al-Ghadab,” an anthem from the hopeful 1960s heyday of Pan-Arabism, sung lustily by the greatest Egyptian heartthrob of the time, Abdel Halim Hafez:

O volcano of rage

uniter of Arabs

Boil upon the plains

Foam upon the sands

Engulf them from the hills and the cannons and the trenches

With rage….

There was no escape from the noise. “If this goes on a second longer I will boil up with rage,” muttered a member of the Mauritanian delegation, clutching his ears. “We should storm the control room,” suggested an Egyptian journalist.

Nine months later Faida Hamdy, a forty-five-year-old municipal inspector in the provincial Tunisian town of Sidi Bouzid, made the mistake of cursing an unlicensed fruit vendor. By some accounts she slapped the young man, twenty-six-year-old Muhammad Bouazizi. Seeing the scale he was using confiscated once again, Bouazizi promptly purchased a canister of gasoline, walked to the town’s main square, doused himself, and struck a match. He died of his injuries eighteen days later, a few days too early to hear of the momentous chain of events sparked by his act of despair.

An outpouring of sympathy for Bouazizi had, in fact, united many Arabs in what could truly be called a volcano of youthful rage against their rulers. Within six weeks of Bouazizi’s death, President Ben Ali of Tunisia had fled into exile after twenty-three years in power. Egypt’s president since 1981, Hosni Mubarak, had resigned in ignominy as millions of his people bayed in the streets for his departure. The popular revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt had in turn spawned copycat movements from Morocco and dirt-poor Yemen to the prosperous island kingdom of Bahrain in the Persian Gulf.

Even Qaddafi’s quixotic regime, with its oil riches and purported adherence to direct democracy through “people’s committees,” faced its most serious challenge since his seizure of power in 1969. Live gunfire from his security forces, purportedly backed by African mercenaries, with hundreds of casualties, failed to quell the protests surging across the eastern half of Libya, most of which by February 23 was reported to be outside of Qaddafi’s control. From a pirate radio station in Benghazi, Libya’s second-largest city, came emotive appeals to join the revolt against “the dog Qaddafi and his Mafia.” “Bless our brothers in Tunisia and Egypt, and god bless Muhammad Bouazizi!” shouted one excited voice at the mike. “May god give patience to his mother. He is the crown on the head of the Arabs!”

Despite wide variations in the nominal forms of government in all these countries, as well as contrasting levels of wealth and education and urbanization, the pattern and shape of the unrest, and the grievances that provoked it, looked everywhere much the same. Arab rulers had grown too isolated, too inflated with pretense and hypocrisy, and too complacently confident in the power of their police. Their overwhelmingly youthful populations suffered perpetual humiliation at the hands of government officials, faced dim work prospects, and had little means of influencing politics. They felt, in the famous words of the Syrian playwright Saadallah Wannous, that they were “sentenced to hope.” More sophisticated and exposed to the world than the generation that ruled them, they had lost faith in the whole patriarchal construct that seemed to hem in their lives.

Advertisement

In retrospect it was perhaps not surprising that the first of these revolts should have erupted in Tunisia, a country whose modest economic success, friendliness to tourism, and pageantry of electoral landslides for the ruling party obscured the stifling reality of a nasty police state. Ben Ali’s kleptocracy had even fewer excuses than its Arab peers for crushing every form of dissent. It faced no real threats, externally or internally, but treated its relatively well-educated and predominantly middle-class people with patronizing contempt. When Tunisian police went too far in trying to suppress the rash of riots that broke out in December in provincial towns like Sidi Bouzid, shooting protesters with live fire, outrage spread both socially and geographically. Soon Tunisia’s wealthier coastal cities were in turmoil, with students, professional groups including lawyers and doctors, and trade unionists all taking to the streets.

As the daily protests grew in size and boldness, Ben Ali’s daunting police force began to crumple. He ordered his army in but it refused to shoot. Other institutions, such as the parliament and press, were so dominated by the ruling party that they could not function as forums to absorb public anger. The regime began to retreat, but its tossing of concessions and apologies only revealed its underlying brittleness. Heeding warnings from the army that he was now in personal danger, Ben Ali flew into exile on January 14. His henchmen played a final desperate card, unleashing loyalist plainclothes saboteurs to create an atmosphere of chaos.

But it was too late. With the army hunting down small bands of Ben Ali militiamen, and citizens forming their own patrols across the country, the wave of looting and vandalism lasted barely two days. State television, stultifyingly bland and adulatory for decades, almost overnight replaced the al-Jazeera satellite channel as a trusted source of news. One female presenter interrupted her chat show and in a sudden epiphany stared open-eyed at the camera. “I just realized,” she said in wonder, “I don’t have to listen to the policeman in my head anymore.”

Tunisia’s revolution now looks pretty much complete. Continued crowd pressure first forced the rump government to fire ministers associated with Ben Ali, and then to dissolve his party, which had ruled continuously since Tunisia’s independence in 1956. In recent weeks exiles have returned, censorship has been abandoned, and political prisoners have been amnestied. Elections are scheduled for August.

It was in the midst of Tunisia’s turmoil, but well before the fall of Ben Ali, that a group of youthful activists in Cairo agreed to call for protests on January 25. The date had long been marked on official calendars as Police Day, in commemoration of the bloody siege by British troops of an Egyptian police post in the Suez Canal city of Ismailia in 1952. The Mubarak government, in a sign of its increasing reliance on police repression, had recently declared the day a national holiday.

By all accounts no one in the room in which the activists met, neither socialist agitators for workers’ rights, representatives of the Muslim Brotherhood youth wing, nor the liberal secularists behind an antigovernment protest group called April 6, expected a big turnout for what they billed as a Day of Rage. They thought, at most, that a modest show of force might embarrass the government into removing Egypt’s hated minister of interior, Habib al-Adly, a sinister figure widely held responsible for police abuse and electoral fraud.

But they did have a few tricks up their sleeves. One was the Facebook group that had formed in protest against the killing by police thugs of a young businessman who was active on the Internet, Khaled Said, the previous summer. Its more than 300,000 members, mostly middle-class, formed a useful pool of recruits. The April 6 group, which had for two years organized periodic demonstrations that rarely gathered more than a few hundred people, had also recently started studying other nonviolent movements aimed at expressing “people power.” The Arabic-language manuals and videos it downloaded from the Internet explained, among other things, how to surprise riot police by having demonstrators converge from several directions at once, how to make simple body armor, and how to mitigate the effects of tear gas.

Advertisement

There was also serendipity. Between their announcement of the event and its actual date, Ben Ali’s government in Tunisia fell. Suddenly, here was proof that what had seemed an impossible dream could actually happen. In fact, some 25,000 people in Cairo joined the January 25 marches, and as many as 20,000 in Alexandria. These were tiny numbers compared to what was soon to come, yet the government showed its nervousness by hurling large numbers of riot police against the protesters, arresting and brutalizing hundreds of them, and beginning a shutdown of communications that soon halted Internet and cell phone services across the country.

The harshness of this crackdown backfired. After Friday prayers on January 28, it was not tens but hundreds of thousands of ordinary Egyptians who poured into the streets, amazement written on faces as they realized how widely their own sense of anger was shared. Crucially, their numbers were boosted by the full strength of the Muslim Brotherhood, whose aging leaders, sensing the regime’s rising panic, belatedly heeded younger members and threw the weight of Egypt’s largest and most disciplined opposition force into the movement. The chants that went up, seemingly spontaneously, called not for reform, not for bread, and not for the heads of a few ministers, but for the fall of the regime and Mubarak’s exit.

Thereafter, events in Egypt very much followed Tunisia’s script, albeit on an immensely bigger scale generating far greater resonance. Under Ben Ali and his predecessor, Habib Bourguiba, Tunisia had been something of a hermit state, shying from regional affairs. Its local dialect, inflected with French and quaint archaicisms, is strange to the ears of other Arabs. Egypt, by contrast, had been the wellspring of a modern, urban Arab culture since the 1920s and the heart of Arabism since the 1950s. Egyptian armies fought four wars for Palestine, the dearest cause to Arabs, generations of whom were raised on Egyptian songs, films, and literature.

During the three decades of Hosni Mubarak’s rule, Egypt grew increasingly irrelevant. Grinding poverty persisted in the most populous Arab country, reducing its relative weight as rival economies in Turkey and the Gulf flourished. Its culture became inward-looking, focused on travails and hardships that meant little to other Arabs. Its close alignment to America reduced its political role to that of a pawn. Not only Egyptians themselves but all their neighbors were pained and puzzled by this loss of stature. To a great extent, it was the product of Mubarak’s own character.

Twenty-seven years ago, which is to say three years into his thirty-year reign, Hosni Mubarak told a surprised American interviewer that he was building democracy for his people. The practice of democracy, Egypt’s president said, was something he had learned to appreciate while in the army. “We really do have democracy,” the former air force chief insisted.

Whenever you adopt any decision in war, you have to listen to all the specialists who argue, who argue with the leader…. We have to discuss everything openly and deliberately. Then the commander makes his decision.

Mubarak may have been dissembling. Despite his Perry Mason persona—that solemn baritone delivery, the owlish glare and bull-necked stolidity—Egypt’s president was not incapable of fibbing, particularly to a visiting American whom he, like many Egyptians (and especially one who received endless US congressional delegations), might assume to be hopelessly naive. Yet it is equally possible that he was being sincere. If we assume that Mubarak really did like his idea of democracy, and believed Egypt’s brass-heavy and rigidly hierarchical military to be a model of democracy in action, and also really thought that he was forging a democratic Egypt, then he obviously had a very narrow understanding of what democracy is.

That is not surprising. The generation and background that produced Egypt’s fallen president were hardly sophisticated. Born into the poor branch of a big clan in a dusty Delta village, Mubarak found escape from Egypt’s stifling class strictures in the air force. Not only did it offer the chance of rapid advancement; there was the thrill of foreign travel, too, albeit only to the Frunze air academy in the Soviet Union. This was during the 1950s and 1960s, a time of constantly threatening war, when Egypt’s military enjoyed unquestioned privilege and prestige.

Mubarak’s mix of toughness, bluntness, and prudence as air force commander during the October War of 1973 impressed Anwar Sadat, who picked him as vice-president in 1975. The assassination of Sadat six years later put Mubarak in charge. His failure to appoint any deputy soon spawned a joke. It was said that Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt’s leader from 1956 to 1970, wanted someone more stupid than himself to be vice-president, and searched the country until he found Sadat. Sadat in turn searched high and low for someone even dumber until he found Mubarak. And as for President Mubarak, well, he was still searching.

The many jokes about Mubarak’s purported dim-wittedness were not strictly fair. Egypt’s president showed little intellectual flair, but compared to his flamboyant predecessors he proved astutely averse to risk-taking. He did, however, show a remarkable lack of imagination. His failure to envision an alternative to his predecessors’ failing policies of state planning and control of capital set Egypt’s economy adrift.

Moreover, his obsession with state security made him suspicious of any political challengers, and his prickliness about his own background made him wary of people with fancy educations and pedigrees. He packed his administrations instead with bland technocrats. Talent leached from government service. Ambitious people who might have entered politics went elsewhere, which is one reason why, now that Mubarak is gone, Egypt’s political field looks dangerously barren.

With internal security forces that may have numbered 1.8 million people by the time of Egypt’s revolution, and with a constitutional set-up that granted regal powers to Mubarak, there was little pressure on Egypt’s president to change. He took his version of “democracy” seriously, listening to advisers before making decisions and, for the most part, allowing his ministers to get on with their jobs. Yet this circle of advisers inevitably aged and shrank. Excepting his son Gamal, who was in his forties and had some experience in global banking, the people Mubarak listened to in his later years were mostly men in their seventies, with similar small-town roots and careers in military and security service. Many had made fortunes for themselves, their families, and friends by cornering markets, monopolizing licenses, and buying vast tracts of state land for resale in lucrative parcels, often using sweetheart loans from state banks demanding no collateral.

As the Mubarak regime drifted with global fashions into a more complete embrace of market economics, some of this windfall wealth did make its way into productive use. Egypt’s middle class expanded. Educational standards rose, and the material culture of slick television advertising, shopping centers, and franchises took hold. But it largely left behind both rural Egypt and growing masses of urban poor. Economists reckoned unemployment to be double the official level of around 10 percent. Food prices in each of the past four years have risen faster than overall inflation, and far faster than wages. According to the latest census, three quarters of Egypt’s 84 million people live in apartments rather than houses, and the country as a whole has fewer rooms than people. According to one report, some 40 percent of the population live on less than $2 a day.

Still, for many Egyptians it was not poverty that was most oppressive, but rather the evidence of an inexorably growing social malaise. This took many forms, from the often unaccountable cruelty of police, to the grasping corruption of petty officials, to the eruption of vicious sectarianism between majority Muslims and the 10 percent Coptic Christian minority. With institutions such as courts, academia, and Egypt’s parliament increasingly delegitimized by state interference, more and more disputes were settled by brute force, whether through the use of hired gangs or by blunt police intervention.

Underlying and aggravating the anxiety generated by such ills was a sense of impotence. As fraudulent elections came and went, producing more men in suits speaking of progress and development, Egyptians felt increasingly trapped outside the insulated virtual world of Mubarak’s state. “We have become an ‘as if’ society,” a young doctor once told me ruefully. “We pretend to work, and they pretend to pay us. We pretend to praise our leaders, and they pretend to represent us. We pretend to obey laws, and they pretend to apply them.”

Such widespread demoralization and loss of pride was hard to formulate or explain. This is one reason why, as the tipping effect of ever greater numbers transformed Egypt’s revolution, fear turned so quickly into exhilaration and joy. Hundreds of Egyptians died and many more were injured in clashes with police during the first of the eighteen tumultuous days leading to Mubarak’s exit. Tahrir or Liberation Square, the symbolic heart of Cairo occupied by hundreds of thousands of protesters in defiance of the regime, was taken and defended with blood. In one particularly surreal moment, state television described an attempt by pro-regime hired thugs riding camels and horses to storm the vast, peaceful sit-in as “an intervention by pro-stability forces.” In fact, those forces had climbed onto rooftops to rain blocks of masonry onto the protesters, attacked them with machetes and Molotov cocktails, and, late in the night, opened fire on them with automatic weapons.

Yet by the time Mubarak’s resignation was announced, during sunset prayers on February 11, the huge, normally traffic-clogged plaza had long since evolved into a round-the-clock carnival city, complete with fire-breathers, stand-up comics, musical performances, and vendors of flags and popcorn. Quite spontaneously, ordinary Egyptians had carved out a space for themselves to act out, for real, the sort of society they had long dreamed of. Volunteers swept streets and manned clinics, while Christians and Muslims guarding the barricades took turns to pray. Children clambered on tanks and wrecked cars to have their pictures taken. Everywhere citizens shouted their opinions, or displayed them on placards.

Many of these were designed to provoke laughter. In response to government propaganda charging that foreign agents were supplying protesters with free Kentucky Fried Chicken, sellers of peanuts and breadsticks labeled their goods “Kentucky.” Sandwich boards demanded that Mubarak leave “so I can get a shave,” “because my arm is tired,” “so I can see my wife—we’re newlyweds.” In the undiminished crowd that continued to gather the day after Mubarak’s resignation had ignited a night of histrionically frenzied nationwide revelry, a young man strutted jauntily around Tahrir with a placard that read, “You can come back now. We were just kidding. You were on candid camera.”

Egyptians pride themselves, and are celebrated among other Arabs, as having “light blood,” an irrepressible propensity for good humor. Mubarak himself and his regime represented the opposite, heavy blood. The satisfaction of throwing off this weight, and doing it by and large peacefully, was instant and profound.

The weight of Egypt’s past has not, by any means, been completely removed. The burden of widespread economic misery remains. Religious tensions also linger, with many Egyptians fearful that the Muslim Brotherhood and perhaps even more extreme Islamist groups may seek to remold society in a theocratic straitjacket. Nor have the vestiges of Egypt’s “deep state” been uprooted. Despite the disgrace of Mubarak’s ruling party, and miniature revolts in state-controlled unions, in the state-owned press, and elsewhere, the large cadre of apparatchiks and enforcers who bolstered Mubarak’s rule is mostly still in place. In rural Egypt, both the police and party apparatus are intact.

As in Tunisia, Egypt’s army stepped in to maintain order during the unrest, and honorably refrained from using force. Eighteen generals of the military high command now officially run the country, having suspended the constitution and disbanded parliament. They have met with opposition figures, declared support for the revolution’s aims, celebrated its martyrs, pledged a transition to civilian rule within six months, and appointed a commission to revise electoral rules. They have also promised to pursue cases of corruption involving former officials, several of whom are under investigation or in custody.

Yet the military’s long legacy as a privileged pillar of the outgoing regime still provokes wariness. Some fear that the army’s haste to hold elections without a more thorough constitutional overhaul suggests a desire to preserve a system whereby a powerful presidency has shielded the military from civilian scrutiny. They also worry that too fast a transition would benefit both the Muslim Brotherhood and the former ruling party, the only political organizations with an entrenched street presence, at the expense of newer, less experienced political forces. Instead, prominent intellectuals have counseled the creation of a stronger, more representative interim government, capable of overseeing a longer and more measured period of transition.

Much of Egypt’s nomenclatura consists of current and former army officers like Mubarak himself. Their inbuilt resistance to truly revolutionary change can be seen in the high command’s reluctance, so far, to countenance any investigation of the Mubarak family, or to outline a comprehensive vision for reform. They have yet to abolish Egypt’s notorious emergency law, or to release remaining political prisoners. Perhaps most disturbingly, the military has charged the last cabinet appointed by Mubarak with continuing to run the daily affairs of government. In short, it is not yet clear whether the generals’ understanding of “democracy” is closer to Mubarak’s than to the hopes so vividly expressed by their people.

Yet there is no doubt that Egypt has changed for good, and with it the wider region. As the increasingly brutal suppression of uprisings in Yemen, Bahrain, and Libya shows, the Egyptian model of massive street uprisings may not work everywhere in the tyranny-prone Middle East. But in Cairo, at least, a newfound sense of empowerment and potential pulses vigorously. It will not be easily muted. “We were always looking at photos, but were never in the picture,” says one of the young April 6 activists, explaining his wonder at the triumph his movement launched. “Now, the photo is us.”

—Tunis and Cairo, February 24, 2011

Editors’ Note: For an account of Egypt’s protest movement since the fall of Mubarak, see Yasmine El Rashidi, “The Revolution Is Not Yet Over,” NYRblog, February 23, 2011.

This Issue

March 24, 2011