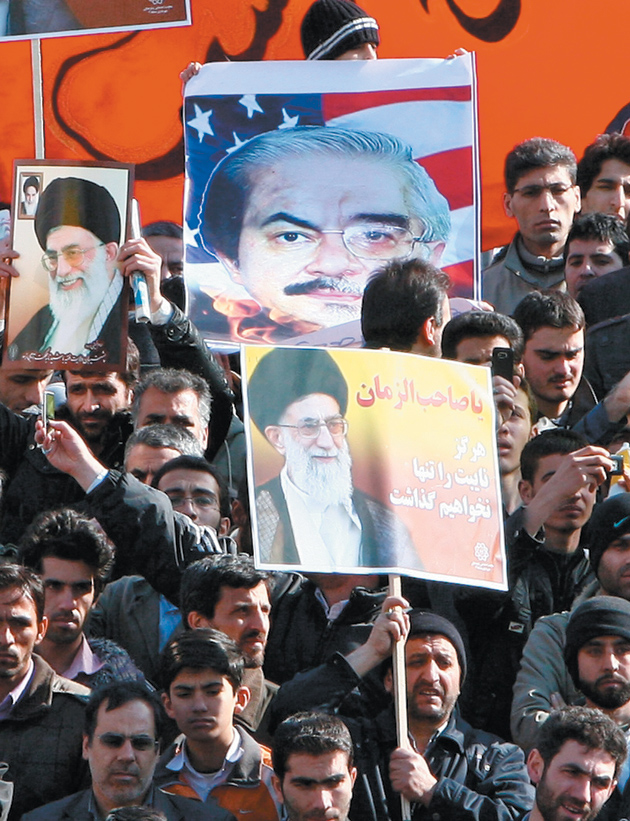

As the Libyan uprising was gathering force in late February, Iran’s presi- dent, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, criticized Libya’s leader, Muammar Qaddafi, for using violence against his own people and advised him and other Middle Eastern heads of state to listen to their publics. The irony was not lost on anyone. Only two weeks earlier, on February 14, Ahmadinejad had sent hundreds of riot police, paramilitary Basijis, and plainclothes, baton-wielding goons to disrupt demonstrations in Tehran called by Mir Hussein Moussavi and Mehdi Karroubi, leaders of the opposition, in solidarity with the people of Tunisia and Egypt. By the end of the day, 1,500 protesters had been arrested; two had been killed.

The next day, 222 of the 290 deputies of the Majlis, Iran’s parliament, approved a resolution to put Moussavi and Karroubi on trial for sedition. Several dozen of the deputies, raising clenched fists, then began to shout out calls to execute the two men. The supposedly “moderate” speaker of parliament, Ali Larijani, quietly joined in. Karroubi and Moussavi, already under house arrest to prevent them from attending the rallies they had hoped to lead, were held incommunicado and denied visits even from their children and families.

Here was another irony, in view of the recent pro-democracy uprisings in the Middle East that Ahmadinejad purported to support. Karroubi, a senior cleric, is a former speaker of parliament; Moussavi was prime minister and guided the country through the difficult years of the Iran–Iraq war in the 1980s. Their “crime” was to have posed a serious challenge to Ahmadinejad as candidates in the 2009 presidential elections, which many Iranians believed were blatantly rigged. Millions of Iranians poured out into the streets to protest when Ahmadinejad’s victory was announced. “Where is my vote?” became the slogan of the protesters, and some even cried “Death to the dictator!”—meaning Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei—an almost unprecedented attack on the regime itself.

But then the security forces and Basijis cracked down with brutal force; according to the government’s own figures, some six thousand were arrested during the election protests. That crackdown, and the mass show trial of protesters broadcast on state television that followed, muted but did not silence the opposition Green Movement. Protests have been attempted periodically since and invariably suppressed by government forces, as they were again in March.

We are witnessing today the intensification of the post-election crackdown, perhaps the severest the country has experienced since the death of Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989. This campaign is aimed not only at the usual dissidents among the intelligentsia, political activists, students, and journalists, but also at men once considered regime insiders. Iran’s leaders have turned against their former comrades-in-arms, fearing that the reformists will take the country in a more liberal direction. In doing so, hard-liners in the regime have joined hands with the Revolutionary Guards, the Intelligence Ministry, and their collaborators in the judiciary, whose chief is appointed by the Supreme Leader, and whose Revolutionary Court is used to try those accused of crimes against the government. The repression has included widespread arrests of reformist politicians, student and women activists, trade union leaders, journalists, lawyers, and public intellectuals; show trials and trials behind closed doors; coerced televised “confessions”; lengthy detentions without trial and long prison sentences after trial; and, perhaps most disturbingly, widespread executions.

Executions have drastically increased under the Ahmadinejad government. According to the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran, eighty-six people were executed in 2005, the year he became president. That figure has risen steadily to 346 in 2008, 388 in 2009, and 542 in 2010—of which only 242 were officially announced. In January 2011 alone, the organization reports, eighty-six people were executed—almost one execution every eight hours. Iran, with its much smaller population, now stands second only to China in the number of executions it carries out.

Among the executed were several leaders of Turk and Baluch ethnic minorities as well as the Dutch-Iranian dual national Zahra Bahrami, who was arrested during the 2009 post-election protests but sentenced to death as a drug trafficker. Drug trafficking—a capital offense in Iran—has become a convenient cover for political executions. Two post-election protesters were hanged at Evin prison on January 24 for “warring against God,” a vague charge that became common after the Islamic Revolution and provides a convenient pretext for imprisoning or killing opponents of the regime. Many more prisoners are on death row.

Harsh prison sentences for political dissidents are becoming increasingly routine. Last year Emadeddin Baghi, an extraordinarily brave journalist and human rights activist who has called attention to the abuse of political prisoners in Iran, was sentenced to six years in prison and stripped of his civil rights for five years, a verdict that will prevent him from voting, running for office, and probably from engaging in journalistic and NGO activities. He was charged with “activities against the national interest” and “publicity in favor of the regime’s enemies”—in part for having interviewed the late Grand Ayatollah Hussein-Ali Montazeri, a critic of the regime, for the BBC in 2007. The regime is also targeting lawyers who defend political dissidents—another practice not common in the past.

Advertisement

The human rights lawyer Shirin Ebadi enjoyed a degree of immunity after winning the Nobel Peace Prize in 2003. But in late December 2008 security authorities raided her offices and her Center for the Defense of Human Rights and subsequently shut down the center. Ebadi is now living in forced exile abroad. Two of the lawyers associated with her center have been arrested. One of them, Mohammad Ali Seifzadeh, was sentenced last year to nine years in prison and barred from practicing law for ten years. And in January Ebadi’s own lawyer, Nasrine Sotoudeh, was sentenced to eleven years in prison and barred from practicing law and traveling out of Iran for twenty years. Sotoudeh’s criticism of Iran’s human rights record and her defense of dozens of political prisoners provoked the decision to punish and silence her.

Torture is hardly new in Iran’s judiciary system, but it has taken particularly grisly forms since the post-election crackdown. Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, personally ordered the shadowy Kahrizak prison in Tehran’s suburbs closed after news leaked out that a number of those held there after the election protests died under torture. In 2009, Karroubi made public letters he had received from families of victims alleging rape of male and female prisoners at this prison. Torture, intimidation, and threats of trial and imprisonment are also being used to extract false confessions from political prisoners, forcing them to implicate themselves or others for allegedly engaging in antigovernment activities or working for foreign powers.

Obsessed with the idea that the US is conspiring to start a velvet revolution in Iran, the regime freely accuses any critic of the government of being an agent of foreign interests. The philosopher Abdolkarim Soroush, living in self-imposed exile in the United States and a vocal critic of the repressive policies of the Iranian government, described in a recent open letter the mistreatment of his son-in-law, Hamed, who was arrested in Iran ten months ago. According to Soroush, Hamed was given a choice: either to face death or to agree to be videotaped denouncing his own wife as a loose woman deserving of divorce, and his father-in-law, Soroush, as a man of numerous vices, affiliated with foreigners, and an enemy of Islam. Soroush writes that Hamed was kept in a freezing morgue for an entire night, in an attempt to extract from him a meaningless denunciation, which he refused to make. He was eventually released and made his way abroad.

It is not uncommon for detainees to wait for months and years to be put on trial. The two American hikers Joshua Fattal and Shane Bauer, who were arrested for allegedly crossing the border into Iran from Iraq in July 2009, were finally put on trial on unsubstantiated charges of espionage on February 6, having spent eighteen months in prison with virtually no contact with their families or lawyer. The trial itself was then held behind closed doors. The lawyer for the two Americans wasn’t allowed see his clients before trial to prepare their defense. After a one-day hearing, the judge postponed the trial, and nothing has been heard of the case since. Not untypically, innocent people remain in prison while officials differ and debate how publicly to handle a particular case.

Since the contested 2009 election, Iran has also witnessed a crackdown on the press, purges of university faculty and administrators, and renewed attempts to interfere with university curricula in the human and social sciences so as to prevent professors from teaching students “dangerous” theories regarding popular sovereignty and the process of democratic transitions.

Women are once again being harassed over matters of dress and their demand for equal rights; and riot police were out in force on March 8 to prevent any demonstrations by women on the occasion of International Women’s Day. The fate of Ali-Akbar Hashemi- Rafsanjani, a former president and generally a centrist and pragmatist, is another indication that the hard-liners are gaining power. Rafsanjani was once considered one of the most powerful men in Iran; but he has been losing ground to the conservatives. One of his sons resigned from his position as head of the Tehran subway; another is under indictment; his daughter was briefly arrested for participation in pro- test demonstrations. Earlier in March, he lost his position as the head of the Assembly of Experts, the body that selects the Supreme Leader.

Advertisement

The Obama administration and the Europeans are asking the UN Human Rights Council to appoint a special investigator to look into human rights violations in Iran. The administration is also publicly naming such violators, for example Iran’s prosecutor-general, Abbas Jafari Dolatabadi, who has been particularly active in pursuing and persecuting protesters, dissidents, and the political opposition. In Iran’s present environment, these measures are likely to fall on deaf ears. Certainly, officials do not like to be fingered in this way, and the charge that the US is supporting the opposition has little effect among Iran’s young and well-informed population. But this does not stop the government from trying to discredit opposition leaders by citing this kind of pressure as evidence of their ties to Washington. President Ahmadinejad certainly seems impervious to the counsel he is giving beleaguered Middle Eastern leaders. “I seriously want from all heads of states to pay attention to their people and cooperate, to sit down and talk, and listen to their words,” he said in his comments in late February. Such sane advice, it seems, applies to others; it does not apply to the government that Ahmadinejad heads.

For the moment, the regime in Iran may feel and act triumphant. Although people may continue to take to the streets, as they did on February 14, mass demonstrations on the scale of the 2009 election protests have not recurred. The security forces and the Revolutionary Guards continue to support the regime, and arrests, trials, and imprisonments have had their own effect, sowing fear in the population.

Ahmadinejad, like President Hugo Chávez of Venezuela and with Khamenei’s support, has cultivated a populist base. He has used plentiful oil revenues to distribute funds to the urban underclass in Tehran and the provinces and to the rural poor in the form of housing credits, local water, road, and similar projects. Cash payments are used to make up for cuts in subsidies for fuel and other basic necessities.

Ahmadinejad travels frequently to the provinces where he promises even more in the way of government support for local pet projects. His anti-Western rhetoric, his stick-it-in-your-face attitude toward the outside world, and even his sometimes outlandish statements on world affairs may raise hackles in the West, but they appeal to a certain element in the Iranian public.

Significant numbers of Iranians in the Basij paramilitary forces, among the families of “martyrs” and casualties of the Iran–Iraq war, and of course in the civil service depend on the government for salaries, pensions, and handouts. The bazaar merchants have at times objected to Ahmadinejad’s tax policies; but thanks again to oil revenues they have done relatively well on a thriving import trade and, so far, have shown no inclination to break ranks with the regime as they did on the eve of the Islamic revolution under the Shah. Awards of noncompetitive contracts for major projects to the Revolutionary Guards have enriched the commanders and allowed the Guards to become major players in the energy, construction, and industrial sectors. These constituencies make up the regime’s base of support, and Ahmadinejad and Khamenei carefully cultivate them.

But this is a regime that is itself also afraid, as the detention and silencing of Karroubi and Moussavi show. Iran’s leaders do not want these two men to continue issuing calls for protests or declarations critical of the government. The opposition has scheduled demonstrations every Tuesday for the foreseeable future—not a happy prospect for the men in power. There have been rumblings in the senior clerical ranks, and Khamenei has had to work hard to prevent defections among them. Deep down, the regime must know that Iranians are carefully watching developments in Egypt and across the Middle East. Iran’s rulers cannot sleep easily thinking that, as in Tunisia and Egypt, a spark may yet ignite a powerful conflagration in Iran itself.

—March 9, 2011

This Issue

April 7, 2011