In his essay “The Proper Means of Regulating Sorrow,”* Dr. Johnson identifies the dreadful uniqueness of grief among the human passions. Ordinary desires, virtuous or vicious, contain within them the theoretical possibility of their satisfaction:

The miser always imagines that there is a certain sum that will fill his heart to the brim; and every ambitious man, like King Pyrrhus, has an acquisition in his thoughts that is to terminate his labours, after which he shall pass the rest of his life in ease or gaity, in repose or devotion.

But grief, or “sorrow,” is different in kind. Even with painful passions—fear, jealousy, anger—nature always suggests to us a solution, and with it an end to that oppressive feeling:

But for sorrow there is no remedy provided by nature; it is often occasioned by accidents irreparable, and dwells upon objects that have lost or changed their existence; it requires what it cannot hope, that the laws of the universe should be repealed; that the dead should return, or the past should be recalled.

Unless we have a religious belief that envisages the total resurrection of the body, we know that we shall never see the lost loved again on terrestrial terms: never see, never talk and listen to, never touch, never hold. In the quarter of a millenium since Johnson described the unparalleled pain of grief, we—we in the secularizing West, at least—have got less good at dealing with death, and therefore with its emotional consequences. Of course, at one level we know that we shall all die; but death has come to be looked upon more as a medical failure than a human norm. It increasingly happens away from the home, in hospital, and is handled by a series of outside specialists—a matter for the professionals. But afterward we, the amateurs, the grief-struck, are left to deal with it—this unique, banal thing—as best we can. And there are now fewer social forms to surround and support the grief-bearer.

Very little is handed down from one generation to the next about what it is like. We are expected to suffer it in comparative silence; being “strong” is the template; wailing and weeping a sign of “giving in to grief,” which is held to be a bad way of “dealing with it.” Of course, there is the love of family and friends to fall back on, but they may know less than we do, and their concerned phrases—“It does get better”; “Two years is what they say”; “You are looking more yourself”—are often based on uncertain authority and general hopefulness. Death sorts people out: both the grief-bearers and those around them. As the survivor’s life is forcibly recalibrated, friendships are often tested; some pass, some fail. Co-grievers may indulge in the phenomenon of competitive mourning: I loved him/her more, and with these tears of mine I prove it. As for the sorrowing relicts—widow, widower, or unwed partner—they can become morbidly sensitive, easily moved to anger by both too much intrusiveness and too much distance-keeping. They may even experience a strange competitiveness of their own: an irrational need to prove (to whom?) that their grief is the larger, the heavier, the purer (than whose?).

A friend of mine, widowed in his sixties, told me, “This is a crappy age for it to happen.” Meaning, I think, that if the catastrophe had happened in his seventies, he could have settled in and waited for death; whereas if it had happened in his fifties, he might have been able to restart his life. But every age is a crappy age for it to happen, and there is no correct answer in that game of would-you-rather. How do you compare the grief of a young parent left with small children to that of an aged person amputated from his or her partner of fifty or sixty years? There is no hierarchy to grief, except in the matter of feeling. Another friend of mine, widowed in a moment after fifty years of marriage—the knot of people by a baggage carousel in the arrivals hall turned out to be surrounding her suddenly dead husband—wrote to me: “Nature is very exact in the matter. It hurts just as much as it is worth.”

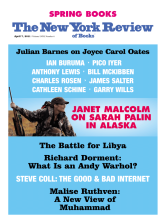

Joan Didion had been married to John Gregory Dunne for forty years when he died in mid-sentence while on his second pre-dinner whisky in December 2003. Joyce Carol Oates and Raymond Smith had been together for “forty-seven years and twenty-five days” when Smith, in hospital but apparently recovering well from pneumonia, was swept away by a secondary infection in February 2008. Both literary couples were intensely close yet noncompetitive, often working in the same space and rarely apart: in the case of Didion-Dunne, for a “week or two or three here and there when one of us was doing a piece”; in the case of Oates-Smith, no more than a day or two. Didion realized after Dunne’s death that “I had no letters from John, not one” (she does not say if he had any from her); while Oates and Smith “had no correspondence—not ever. Not once had we written to each other.”

Advertisement

The similarities continue: in each marriage the woman was the star; each of the dead husbands had been a lapsed Catholic; neither wife seems to have imagined in advance her transformation into widow; and each left her husband’s voice on the answering machine for some while after his death. Further, each survivor decided to chronicle her first year of widowhood, and each of their books was completed within those twelve months.

Yet Oates’s A Widow’s Story and Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking could not be more different. Though Didion’s opening lines (the fourth of which is “The question of self-pity”) were jotted down a day or two after Dunne’s death, she waited eight months before beginning to write. Oates’s book is largely based on diary entries, most from the earliest part of her year: so in a 415-page book, we find that by page 125 we have covered just a week of her widowhood, and by page 325 are still only at week eight. While both books are autobiographies, Didion is essayistic and concise, seeking external points of comparison, trying to set her case in some wider context. Oates is novelistic and expansive, switching between first and third persons, seeking (not with unfailing success) to objectify herself as “the widow”; and though she occasionally reaches for the handholds of Pascal, Nietzsche, Emily Dickinson, Richard Crashaw, and William Carlos Williams, she is mainly focused on the dark interiors, the psycho-chaos of grief. Each writer, in other words, is playing to her strengths.

That both Didion and Oates limit their books to the first year of their widowhoods is logical. Long-married couples develop a certain rhythm, gravity, and coloration to the annual cycle, and so those first twelve months of widowhood propose at every turn a terrible choice: between doing the same as last year, only this time by yourself, or deliberately not doing the same as last year, and thereby perhaps feeling even more by yourself. That first year contains many stations of the cross. For instance, learning to return to a silent, empty house. Learning to avoid what Oates calls “sinkholes”—those “places fraught with visceral memory.” Learning how to balance necessary solitude and necessary gregariousness. Learning how to react to friends who mystifyingly decline to mention the name of the lost partner; or colleagues who fail to find the right words, like the “Princeton acquaintance” who greeted Oates “with an air of hearty reproach” and the line, “Writing up a storm, eh, Joyce?” Or like the woman friend who offers her the consolation that grief “is neurological. Eventually the neurons are ‘re-circuited.’ I would think that, if this is so, you could speed up the process by just knowing.“

The intention is kindly; the effect, patronizing. Oh, so it’s just a question of waiting for those neurons to settle? Then there are practical problems: for instance, the garden your husband lovingly tended, but in which you are less interested; you may enjoy the results, but rarely joined him in visits to the garden center. So do you faithfully replicate the same work, or do you unfaithfully let the garden look after itself? Here, Oates finds a wise third way: where Smith planted only annuals, she replants with nothing but perennials, asking the nurseryman for “anything that requires a minimum of work and is guaranteed to survive.”

Which is the problem confronting the widow: how to survive that first year, how to turn into a perennial. This involves surmounting fears and anxieties for which there is no training. Previously, Oates rated as “the most exquisite of intimacies” the ability to occupy the same space as Ray for hours, without the need to speak; now, there is a quite different order of silence. “What I am,” Oates writes, “begins to be revealed now that I am alone. In such revelation is terror.”

At one point she thinks “half-seriously of sending an email to friends” asking if she might hire one of them “if you could overcome the scruples of friendship and allow me to pay you in some actual way—to keep me alive for a year, at least?” She wants to be a “good widow” and asserts that “I will do what Ray would want me to do,” while also—classically—blaming Ray for having put her in this state; she is sleepless and irritable; she envisages her grief and insomnia lasting for a decade, while also doubting that her mourning is “real.” She muses on suicide, though more in a theoretical than practical way—while also knowing that “thinking seriously of suicide is a deterrent to suicide.” She finds that work comes much harder, noting of a new short story that it “will require literally weeks” (a complaint that will make most other writers chuckle). And, like many of the grief-struck, she fears for her own mental state: “Half the time, I think I must be totally out of my mind.”

Advertisement

Oates excellently conveys the disconnect between the inwardly chaotic self and the outwardly functioning person (and she is functioning again with remarkable rapidity—correcting proofs and working on a story within a week of Smith’s death, back on the literary road within three). She is certainly less in control than she seems to outsiders, but probably more in control than she feels to herself. The grief-struck frequently act in ways that could be seen as either half-sane or half-mad, but rarely give themselves the benefit of the doubt. For instance, the day after Ray’s death, Oates goes to their bedroom closet and throws out not her husband’s clothes, but half of her own clothes. She does it as punishment for her own vanity, and because these garments speak of a time when she wore them happily with Ray—so now they have no meaning or merit. It is in such moments of rational irrationality that the nature of grief is made plain to us.

Most of the grief-struck suffer—especially in the first months—from a terror of forgetting their lost one. Often the shock of death wipes out the memory of earlier times, and there is a morbid fear that it will never be recovered: that the lost one will now be twice lost, twice killed. Joyce Carol Oates does not appear to have suffered this fear; instead, she suffers a rarer, more interesting, and potentially more corrosive one—that of never having fully known her husband in the first place.

Oates and Smith married in January 1961, and her portrait of their first years together—the time when secrets are exchanged, concentration on the other is at its fullest, and the lineaments and rules of the partnership are worked out—is both vivid and touching. It is also a relationship colored more by the 1950s than the 1960s. Oates was eight years younger than Smith; they were shy of one another, even in marriage; by her own account she never wanted to upset him, let alone argue with him. Thus, for example:

It was years before I summoned up the courage to suggest to Ray that I did not really like some of the music he frequently played on our stereo—such macho-hectic compositions as Prokofiev’s Alexander Nevsky, the chorale ending of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony with its relentless joy joy joy like spikes hammered into the skull, much of Mahler…

Fortunately, it seems that Smith was only in touch with the “macho-hectic” side of masculinity when lowering a stylus onto vinyl. He comes across as quiet, loyal, and domesticated; a cook, a keen gardener, and a meticulous editor of the Ontario Review. He read most of his wife’s nonfiction but very little of her fiction. It is, of course, a famously large oeuvre (fifty-five novels plus hundreds of short stories); even so, the reader is brought up short when Oates writes: “I don’t believe that Ray read my first novel With Shuddering Fall.” Which is the more astonishing: that he didn’t read it, that she isn’t sure whether or not he did, or that she expresses neither annoyance nor disappointment at his omission? But then her opinions on the relationship between the sexes are somewhat unusual:

To a woman, the quintessential male is unknowable, elusive.

In our marriage it was our practice not to share anything that was upsetting, depressing, demoralizing, tedious—unless it was unavoidable.

Women are inclined to console men, all women, all men, in all circumstances without discretion.

The ideal marriage is of a writer and her/his editor.

A wife must respect her husband’s family even when—as it sometimes happens—her husband does not entirely respect them.

A wife must respect the otherness of her husband—she must accept it, she will never know him fully.

This sounds like shyness raised to marital principle; and it brings with it the danger that when the wife becomes a widow and goes through her husband’s papers, she will find out things she barely suspected. In Ray Smith’s case: a nervous breakdown, a love affair at a sanatarium, a psychiatrist’s description of him as “love-starved,” and further evidence of a difficult, distant relationship with his father. “For all that I knew Ray so well,” she concludes, “I didn’t know his imagination.” Nor, perhaps, did he know hers, given that he rarely read her fiction. But he was “the first man in my life, the last man, the only man.”

In some ways, autobiographical accounts of grief are unfalsifiable, and therefore unreviewable by any normal criteria. The book is repetitive? So is grief. The book is obsessive? So is grief. The book is at times incoherent? So is grief. Phrases like “Friends have been wonderful inviting me to their homes” are platitudes; but grief is filled with platitudes. The chapter headed “Fury!” begins:

Then suddenly, I am so angry.

I am so very very angry, I am furious.

I am sick with fury, like a wounded animal.

A kick of adrenaline to the heart, my heart begins thudding rapid and furious as a fist slamming against an obdurate surface—a locked door, a wall.

If a creative writing student turned this in as part of a story, the professor might reach for her red pencil; but if that same professor is writing a stream-of-consciousness diary about grief, the paragraph becomes strangely validated. This is how it feels, and what is grief at times but a car crash of cliché? A few pages later, Oates is reflecting on the fact that she now has a private identity as “Joyce Smith” or “Mrs. Smith,” official widow, and a public identity under her full three-part writing name:

“Oates” is an island, an oasis, to which on this agitated morning I can row, as in an uncertain little skiff, with an unwieldy paddle—the way is arduous not because the water is deep but because the water is shallow and weedy and the bottom of the skiff is endangered by the rocks beneath. And yet—once I have rowed to this island, this oasis, this core of calm amid the chaos of my life—once I arrive at the University…

The image of a skiff and a water- crossing is dead and unrevivable, no matter how extended? It doesn’t matter. This sentence may be the first in world literature where the writer imagines you can row to an oasis? But you don’t understand: incoherence of imagery is a fair representation of the acutely distracted and fractured mind. You mean, she didn’t even notice when reading the proofs? Again, it doesn’t matter whether she did or didn’t. You asked for a sense of what it is like: this is what it is like.

Grief dislocates both space and time. The grief-struck find themselves in a new geography, where other people’s maps are only ever approximate. Time also ceases to be reliable. C.S. Lewis, in A Grief Observed, describes the effect on him of his wife’s death:

Up till this I always had too little time. Now there is nothing but time. Almost pure time, empty successiveness.

And this unreliability of time adds to the confusion in the sorrower’s mind as to whether grief is a state or a process. This is far from a theoretical matter. It is at the heart of the question: Will it always be like this? Will things get better? Why should they? And if so, how will I tell? Lewis admits that when he started writing his book,

I thought I could describe a state; make a map of sorrow. Sorrow, however, turns out to be not a state but a process. It needs not a map but a history.

Probably, it needs both at the same time. We might try to pin it down by saying that grief is the state and mourning the process; yet to the person enduring one or both, things are rarely clear, and the “process” is one that involves much slipping back into the paralysis of the “state.” There are various markers: the point at which tears—regular, daily tears—stop; the point when the brain returns to normal functioning; the point when possessions are disposed of; the point when memory of the lost one begins to return. But there can be no general rules, nor standard time-scale. Those pesky neurons just can’t be relied upon.

What happens next, when the state and the process are, if by no means complete, at least established and recognizable? What happens to our heart? Again, there are those confident surrounding voices (from “How could he/she ever marry again after living with her/him?” to “They say the happily married tend to remarry quickly, often within six months”). A friend whose long-term lover had died of AIDS told me, “There’s only one upside to this thing: you can do what you fucking well like.” The trouble is that when you are in sorrow, most notions of “what you like” will contain the presence of your lost love and the impossible demand that the laws of the universe be repealed. And so: a hunkering-down, a closing-off, a retreat into the posthumous faithfulness of memory? Raymond Smith didn’t much like Dr. Johnson, finding him too didactic, and preferring the Doctor of Boswell’s account to that of his own writings. But on sorrow, Johnson is not so much didactic as wise, clear, and decisive:

An attempt to preserve life in a state of neutrality and indifference, is unreasonable and vain. If by excluding joy we could shut out grief, the scheme would deserve very serious attention; but since however we may debar our lives from happiness, misery will find its way at many inlets, and the assaults of pain will force our regard, though we may withhold it from the invitations of pleasure, we may surely endeavour to raise life above the middle point of apathy at one time, since it will necessarily sink below it at another.

So what constitutes “success” in mourning? The ability to return to concentration and work; the ability to rediscover interest in life, and take pleasure in it, while recognizing that present pleasure is far from past joy. The ability to hold the lost love successfully in mind, remembering without distorting. The ability to continue living as he or she would have wanted you to do (though this is a tricky area, where the sorrowful can often end up giving themselves a free pass). And then what? Some form of self-sufficiency that avoids neutrality and indifference? Or a new relationship that will either supplant the lost one or, perhaps, draw strength from it?

There is another strange parallel between The Year of Magical Thinking and A Widow’s Story. By the time each book came out, many readers would know one additional key fact not covered in the text. In Didion’s case, the death of her daughter Quintana (which the author deals with in a subsequent edition); in Oates’s, her remarriage to a neuroscientist, whose existence is hinted at rather coyly on the last page. You could argue that those writing about grief make their own literary terms more than most; but even so, in Oates’s case there is something unhappy in the omission. She is writing about a year that began on February 18, 2008; we know from her own mouth (in an interview with the London Times) that she met her second husband in August 2008, they started going on walks and hikes in September, and were married in March 2009. If Didion posed “the question of self-pity” in the first lines of her book, Oates, in a chapter called “Taboo,” similarly approaches the difficult heart of the matter:

It’s a taboo subject. How the dead are betrayed by the living.

We who are living—we who have survived—understand that our guilt is what links us to the dead. At all times we can hear them calling to us, a growing incredulity in their voices You will not forget me—will you? How can you forget me? I have no one but you.

But the theme is no sooner announced than set aside; indeed, when Oates comes back to the idea of “betraying” her husband, it is in the much narrower context of disclosing to the reader secrets about Ray Smith’s family and upbringing. But she does this, she explains, because “there is no purpose to a memoir, if it isn’t honest. As there is no purpose to a declaration of love, if it isn’t honest.” Her book ends with a chapter headed “The Widow’s Handbook,” which reads in its entirety:

Of the widow’s countless death-duties there is really just one that matters: on the anniversary of her husband’s death the widow should think I kept myself alive.

But if she is also thinking “I might be getting married in a few weeks’ time,” does this not change the nature of that statement? This isn’t a moral comment: Oates may quote Marianne Moore’s line that “the cure for loneliness is solitude,” but many people need to be married, and therefore, at times, remarried. However, some readers will feel they have a good case for breach of narrative promise. And what about all those perennials she planted?

When Dr. Johnson wrote “The Proper Means of Regulating Sorrow” he was not yet widowed. That event was to occur two years later, when he was forty-three. Twenty-eight years afterward, in a letter to Dr. Thomas Lawrence, whose wife had recently died, Johnson wrote:

He that outlives a wife whom he has long loved, sees himself disjoined from the only mind that has the same hopes, and fears, and interest; from the only companion with whom he has shared much good or evil; and with whom he could set his mind at liberty, to retrace the past or anticipate the future. The continuity of being is lacerated; the settled course of sentiment and action is stopped; and life stands suspended and motionless, till it is driven by external causes into a new channel. But the time of suspense is dreadful.

This Issue

April 7, 2011

-

*

The Rambler, No. 47, August 28, 1750. ↩