Even in his lifetime the legend of Mahatma Gandhi had grown to such proportions that the man himself can be said to have disappeared as if into a dust storm. Joseph Lelyveld’s new biography sets out to find him. His subtitle alerts us that this is not a conventional biography in that he does not repeat the well-documented story of Gandhi’s struggle for India but rather his struggle with India, the country that exasperated, infuriated, and dismayed him, notwithstanding his love for it.

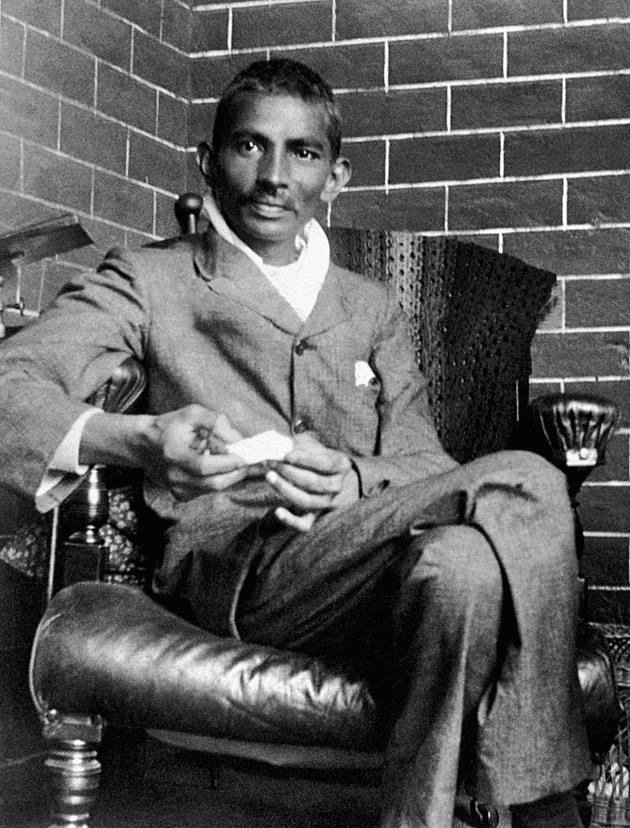

At the outset Lelyveld dispenses with the conventions of biography, leaving out Gandhi’s childhood and student years, a decision he made because he believed that the twenty-three-year-old law clerk who arrived in South Africa in 1893 had little in him of the man he was to become. Besides, his birth in a small town in Gujarat on the west coast of India, and childhood spent in the bosom of a very traditional family of the Modh bania (merchant) caste of Jains, then the three years in London studying law are dealt with in fine detail and with a disarming freshness and directness in Gandhi’s Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth. Lelyveld’s argument is that it was South Africa that made him the visionary and leader of legend. He is not the first or only historian to have pointed out such a progression but he brings to it an intimate knowledge based on his years as a foreign correspondent for The New York Times in both South Africa and India and the exhaustive research he conducted with a rare and finely balanced sympathy.

Having accepted the brief of assisting as a translator in a civil suit between two Muslim merchants from India, Gandhi presented himself in a Durban magistrate’s court on May 23, 1893, just the day after his arrival, dressed in a stylish frock coat, striped trousers, and black turban, and was promptly ordered to remove the turban. He refused, left the courtroom, and fired off a letter to the press in protest. This was his first political act, predating the incident of being thrown off a train by an Englishman who objected to traveling with a “colored man” made famous by Richard Attenborough’s film Gandhi and Philip Glass’s opera Satyagraha. Remarkably for an Indian, this seems to have been his first encounter with colonial arrogance and in his autobiography he said it made him resolve to stay and “root out the disease” of “color prejudice.” It was the start of what Erik Erikson was to call his “eternal negative” but it is also a simplification, Lelyveld points out, of a much more convoluted attitude toward race, color, and caste that he brought with him from India.

It was a shock to Gandhi to find that in South Africa he was considered a “coolie”—in India the word is reserved for a manual laborer, specifically one who carries loads on his head or back. In South Africa the majority of Indians was composed of Tamil, Telugu, and Bihari laborers who had come to Natal on an agreement to serve for five years on the railways, plantations, and coal mines. They were known collectively as “coolies,” and Gandhi was known as a “coolie barrister.”

Still, he had a touching faith in Queen Victoria’s proclamation of 1858 that formally extended British sovereignty over India and promised its inhabitants the same protections and privileges as all her subjects, voicing her wish that her Indian subjects “be freely and impartially admitted to offices in our service.” So when the Anglo-Boer War broke out in 1899 and later the Zulu rebellion of 1906, he led the Indian community—he had joined the Natal Indian Congress—in offering its service to the colonial power “as full citizens of the British Empire, ready to shoulder its obligations and deserving of whatever rights it had to bestow.” He was proud of his command of the unit of Indian stretcher-bearers—not, one would think, a likely start for one who came to be regarded as the man who inspired India’s struggle, and struggles elsewhere in the world, for freedom.

It was when the so-called Black Act was passed in 1906, forcing Indians living in the Transvaal to register, that he held meetings and urged his fellow men to burn the permits they were required to carry and found himself being marched off, as he wrote, to

a prison intended for Kaffirs…. We could understand not being classified with the whites, but to be placed on the same level as the Natives seemed too much to put up with. It is indubitably right that the Indians should have separate cells. Kaffirs are as a rule uncivilized—the convicts even more so. They are troublesome, very dirty and live almost like animals.

Africans could hardly ignore Gandhi’s disparagement of them: Zulu newspapers took note that the Indians volunteered to work for the “English savages in Natal” and even an Indian publication in England called Gandhi’s readiness to serve the whites “disgusting.” It was only much later—and with the judicious addition of hindsight—that Gandhi claimed that “my heart was with the Zulus” and claimed that the cruelty he had witnessed against them was “the major turning point of his life spiritually,” the one that made him turn to nonviolence as a strategy for resistance. This came to be known as satyagraha, which translates literally as “truth force” or “firmness in truth.”

Advertisement

This was the strategy he used in 1913 when he launched a campaign against the so-called “head tax,” the payment required of every Indian who had completed the terms of his agreement and wished to remain in the Transvaal. It did not involve the native population at all but it ignited a rebellion by indentured labor, a turn unforeseen by Gandhi himself. Indians walked off plantations, railroads, mines, and whatever services employed them in the cities, creating a strike on a scale that made it the first significant event in Gandhi’s career. “I was not prepared for this marvelous awakening,” he said. Becoming “a self-propelled whirlwind,” Lelyveld writes, he traveled by rail from one rally to another, exhorting the strikers to allow themselves to fill the jails to overflowing. (Africans were to take note and use the same strategy of passive resistance in their own struggle to come.) General Jan Smuts called out the army to suppress the strike, which it did with ferocity.

When the strike was called off, Gandhi was hailed by crowds of thousands and now saw himself as the representative not only of Indian settlers of the merchant class but of the lowest of castes, the indentured laborers he had once ignored. He had found his vocation but the outcome—the Indian Relief Act of 1914—fell far short of what the agitation had called for. Lelyveld points out, as did critics at the time, that Indians still had no political rights in South Africa—and did not for another century. The system of indentured labor eventually ended, but that had not been one of Gandhi’s demands.

While these huge public turmoils were taking place, Gandhi was experimenting with personal and domestic changes as well: first by establishing a small, self-reliant, rural commune near Durban, Phoenix Farm, with his family and a few friends. Here they were expected to share equally in all duties—editing and printing his newspaper, Indian Opinion, as well as working on the land. He set forth his principles of the ideal life—vegetarianism, nature cures for all ills, home schooling for his children, extreme austerity in all spheres of life. “Meagerness” was the standard by which diet was to be measured, a full meal being “a crime against man and God.” He decided that “no man living the physical or animal life can possibly understand the spiritual or ethical” and took the vow of celibacy; his wife concurred.

Gandhi did not follow the traditional Indian formula: his ashram was based not on religion but on universal humanistic thought. How had this come about? Lelyveld believes that “if there is a single seminal experience in his intellectual development,” it was reading Tolstoy’s The Kingdom of God Is Within You. The Hindu revolutionary Sri Aurobindo went so far as to say, “Gandhi is a European—truly a Russian Christian in an Indian body.”

Lelyveld found that he now more or less abandoned his wife and children in Natal for months at a time, despite bitter complaints of neglect from his wife and eldest son Harilal. (“He feels that I have always kept all the four boys very much suppressed…always put them and Ba last,” Gandhi wrote dispassionately.) When Gandhi’s brother Laxmidas complained that he was failing to meet his family obligations, he replied serenely, “My family now comprises all living beings,” and proceeded to assemble a surrogate family made up of mostly European Theosophists who shared his enthusiasm for Tolstoy and Ruskin. He lived for a while with the young copy editor Henry Polak and his wife Millie, then moved in with the East Prussian Jewish architect Hermann Kallenbach. Together they created another rural “utopia,” Tolstoy Farm, southwest of Johannesburg, and Gandhi seems to have been happier there than he had been anywhere—enjoying bicycle rides and picnics and the friendship of Kallenbach.

This friendship was close—even romantic, Lelyveld suggests—and Kallenbach would have followed Gandhi when he left for India in 1914 if World War I had not broken out, barring him from entering British territory. All Gandhi’s efforts to obtain a visa for him failed, and the two were not to meet again for twenty-three years, by which time Kallenbach had become a Zionist and joined a kibbutz in Israel.

Advertisement

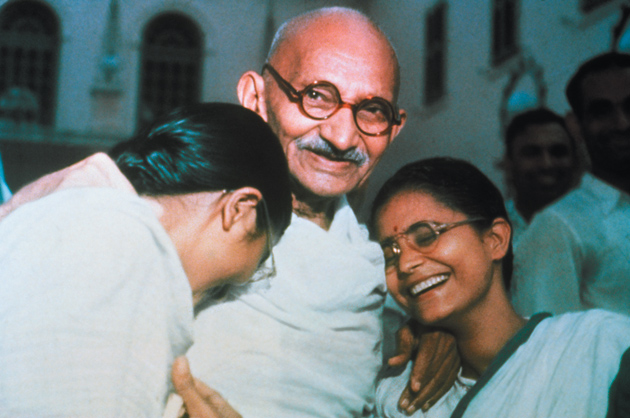

Gandhi had taken a vow to spend his first year back in India traveling throughout the country to acquaint himself with conditions there. He did so by rail, in a third-class compartment. This was to be his lifelong habit and it was required of all his entourage, which became enormous (the Indian poet Sarojini Naidu quipped, “You will never know how much it costs us to keep that saint, that wonderful old man, in poverty!”). His fame as leader of satyagraha on behalf of Indians in South Africa had preceded him and crowds of between 10,000 and 20,000 mobbed him wherever he went, bending to touch his feet to show respect in the Indian way, a habit that annoyed him intensely. “Oh God,” he groaned, “save me from my friends, followers and flatterers!”

What he saw on these journeys made him take up the cause of exploited peasants on the indigo plantations of Bihar and in drought-stricken Kheda where farmers were suffering from high taxation and land confiscation, and of the mill workers in Bombay and Ahmedabad. No longer the natty lawyer, he now dressed like a laborer himself. He had of course been acquainted with the caste system since childhood but the injustice of it that condemned the lower castes to live in poverty and degradation struck him most forcefully when he first attended an Indian National Congress meeting in Calcutta and saw how the Brahmin delegates from South India secluded themselves in enclosed kitchen and dining areas to avoid pollution by the lower castes, and how the public latrines could only be cleaned by scavengers, the “untouchables,” or were left filthy.

The eradication of “untouchability” became a cardinal point of his campaign; the other three of the “four pillars” being the alliance of Hindus and Muslims, promotion of handloom fabrics to promote a self-sustaining industry, and nonviolence in both tactics and discipline. This was to be his dharma, what the historian Judith Brown has called “morality in action.”

In his usual way, he established an ashram, a commune, with family and friends, in Wardha, where he insisted on his rules being observed scrupulously, but there were many rebellions: his wife Kasturba found it hard to live with members of the “untouchable” caste and especially objected to cleaning their chamber pots, a defiance Gandhi found unforgivable. He also berated her severely for entering a temple that refused admission to “untouchables.” He himself rarely visited a temple and never to pray. He led a march to the ancient temple of Vaikom in Travancore that not only forbade “untouchables” from entering but from walking on roads that led to it. Gandhi could not even get past the signs excluding them. He was granted an audience with the priests but it had to be held elsewhere and his demands were firmly set aside. He left defeated and it was more radical leaders like T.K. Madhavan and George Joseph who carried on the campaign.

Ironically, too, Gandhi failed to make a partner in the fight against “untouchability” of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, himself an “untouchable” but a highly educated one with degrees in law and economics who was, like Gandhi, invited to a Round Table Conference on India in London in 1931. Gandhi immediately alienated him by offering “to share the honor…of representing the interests of untouchables.” Ambedkar responded icily, “I fully represent the claims of my community.” He believed that “untouchables were keepers of their own destiny and deserved their own movement.” Gandhi could not approve of a separate electorate for them. He feared that “special representation for untouchables would work to perpetuate untouchability…. ‘Will untouchables remain untouchables in perpetuity?'” In exasperation, Ambedkar finally advocated mass conversion from Hinduism to a religion with no caste system as a solution; this only baffled Gandhi.

As chief executive of the Indian National Congress, Gandhi saw that to create a national party with one national aspiration it was necessary to include the Muslim minority in pursuing the common ground of swaraj, or self-rule. In South Africa he had had good relations with Muslims, but in India he struggled. He had, Lelyveld writes, acquired early Muslim supporters in the Ali brothers, Muhammad and Shaukat, and sympathized with their cause, the return of the Ottoman Caliphate, although this was considered quixotic even by some Muslims and certainly displeased the British. They put the brothers in jail, and in Turkey Mustafa Kemal Atatürk dissolved the Caliphate and sent the last sultan into exile, spelling the end of the so-called Khilafat movement in India. As for Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the leader of the Muslim League, a partnership could have developed—both men were from Gujarat and had been trained as lawyers in England—but they had little else in common and Jinnah could not conceal his suspicion that the Congress Party was interested only in the establishment of the Hindu raj.

Then there was Gandhi’s ardent espousal of the spinning wheel as an instrument of release from the enforced import of British-made cloth. It provided a popular symbol, but it also set off violent riots when mobs took to burning imported goods, and, as Lelyveld writes, no less a patriot than the poet and Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore pronounced it a misguided and doomed campaign. It was Tagore who had given Gandhi the honorific of Mahatma—Great Soul—and Gandhi in return had named him the Great Sentinel, but for all their praise of each other, they had little in common—one an artist and aristocrat, the other an ascetic and a populist. Tagore was appalled by Gandhi’s illogical and unscientific claim that the earthquake that struck Bihar in 1934 was punishment for the sin of untouchability.

As leader of the Congress Party it was for Gandhi to reconcile all these factions and their jostling demands and conflicts. An occasion for unified action was provided in 1919 when British police fired on an unarmed gathering of protesters in Jallianwalla Bagh, an enclosed space in Amritsar, killing many hundreds. The reaction was widespread, and Gandhi launched his non-cooperation movement, asking judges and lawyers to boycott courts, students their schools, and soldiers their units while recipients of medals and honors were asked to return them—as Tagore did his knighthood forthwith. In their effort to halt the movement the British placed Gandhi in prison.

They continued to do so for his acts of defiance, but this in no way diminished his influence. He would start to fast in prison and the nation would hold its breath till he agreed to suspend it. As his body dwindled, Lelyveld observes, his political and spiritual power increased. The fast joined the spinning wheel as a distinctly Gandhian symbol of protest. In 1930 his genius for the inspired and inspiring gesture made him lead a march of two hundred miles from his ashram to Dandi on the Arabian Sea, crowds lining the road to cheer him. With “the beauty and simplicity of a fresh artistic vision,” Lelyveld writes, he bent to pick a handful of salt on the beach in defiance of British taxation of even so lowly and indispensable a commodity. Sarojini Naidu cried, “Hail, Deliverer!” The police arrived with batons, heads were cracked, and Gandhi was sent back to prison in May 1930. Jawaharlal Nehru, the future leader of the Congress Party and India’s first prime minister, commented, “What the future will bring I know not, but the past has made life worth living and our prosaic existence has developed something of epic greatness in it.”

Moments of triumph contain in them the seeds of disintegration. Gandhi, released from prison in January 1931, could not hold the movement together with such gestures, however powerful. A weary Gandhi sought a kind of self-imposed exile, retiring to a small village in the west of India in the summer of 1936, but an ashram (Sevagram, or “Village of Service”) quickly sprung up around him.

At the outbreak of World War II he proposed to support the British war effort, but this was rejected by the Congress Party, which offered no more than support conditional on Britain granting India independence. That was turned down by the Tory government, Churchill making his famous comment that he had not become prime minister to preside over the disintegration of the British Empire. Calls for the British to “Quit India!” then became the rallying cry for one last hard push to obtain freedom. Gandhi was once again placed in detention—in the Aga Khan’s former palace near Poona; his poor wife, still loyally following, was to die there.

Gandhi was released in 1944 and the British government, exhausted by the war and soon to be under a Labour cabinet, hoped for a compromise to which all factions in India would agree. Gandhi left immediately for Bombay to negotiate with Jinnah, who now saw a separate Muslim nation as the only solution. Crowds stoned the train carrying Gandhi, trying to prevent him from making concessions; but Jinnah remained adamant and the partition of India became inevitable. Riots and mob violence between Hindus and Muslims raged through the country. Instead of staying in the capital for the victory celebrations set to take place in August 1947, Gandhi left for Calcutta, leaving it to Nehru to unfurl the national flag at the Red Fort and give his famous speech about a “Tryst with Destiny,” saying that the joyful cries of “Jai Hind!“—Glory to India!—“stink in my nostrils.”

One of the last and most moving sections of Lelyveld’s book has Gandhi in early 1947 walking barefoot from village to village—forty-seven in all—in the Muslim-majority area of Noakhali with his followers, now a small band, singing the Tagore song “Ekla Chalo”—“If no one answers your call, walk alone, walk alone.” The strangest act in this drama, as Lelyveld makes clear, is Gandhi’s choice of such a time for one last “experiment with truth”: he requested the presence of a nephew’s seventeen-year-old daughter, Manu, to come to the stinking, blood-stained scene of carnage and minister to his physical needs—overseeing his diet, giving him his daily bath and oil massage, but also to sleep beside him on his cot, wearing as little clothing as possible, if any, to test his commitment to celibacy. He seems to have thought that if he could subdue the impulse to animal arousal in his body, then the country could subdue its lust for violence. Unable to follow the connection Gandhi had always made between sex and violence, abstinence and nonviolence, even his most devoted followers were shocked, and many left.

The end came in 1947 when Manu asked for permission to leave and Gandhi was persuaded to travel to Delhi, where the new constitution was being drawn up—under the guidance of no other than Dr. Ambedkar. Gandhi seemed to have no interest in making a contribution. Instead, he spent his time praying and fasting in the house of his old friend, the rich industrialist G.D. Birla—for security reasons, he could not stay as he usually did in the scavengers’ colony—while outside Sikhs who had lost their lands to Pakistan were chanting “Death to Gandhi!” and “Blood for blood!” At the nightly prayer meetings that he held in the garden, the orthodox Hindu editor Nahuram Godse, who had been writing fiery articles denouncing what he saw as Gandhi’s pandering to Muslims, brought with him a concealed weapon—Gandhi had refused to let the police search those who attended these meetings—and, pushing aside Manu, who accompanied Gandhi, shot him point-blank. It is said that he fell with the name of God, “Rama, Rama,” on his lips as he had told Manu he hoped to; in fact, he had seemed to be courting death. If ever there was A Chronicle of a Death Foretold, it was his.

He was cremated amid scenes of unparalleled chaos, confusion, and grief, millions attending his funeral—the ultimate irony: it was a state funeral with full military honors—and his ashes were scattered across India and, in 2010, a small portion off the coast of Durban in South Africa. Nehru took over the leadership, making it clear that “Congress has now to govern, not to oppose government.” Central to his vision were a modern military and rapid industrialization. But even he could not have foreseen how thoroughly his vision would overtake Gandhi’s.

When Lelyveld went in search of what might remain of Gandhi, what he found, aside from many archives and letters, were a few pathetic objects in dusty museums—a creaky spinning wheel, garlanded photographs of “The Father of the Nation”—and a few loyal Gandhians still living lives of sacrifice and service against all odds. Yet much remains that Gandhi would recognize as the “eternal India” of poverty and tradition. In the district of Noakhali Lelyveld found the village of Srirampur, where Gandhi had taken refuge, becalmed as if time had come to a halt. Sunlight filters through the palms, rice paddies surround it, men lounge around the tea shop. At the mention of Gandhi’s name, someone steps forward to point out the sites associated with him—this was where his hut once stood, this the shrine under a banyan tree where he had lingered:

Voices become hushed. His name evokes a formal reverence, even among those who have never known the details of his time here…and the killings are remembered as a long-ago typhoon, another kind of disaster.

Lelyveld has exploded so many myths and heaped up so many defeats that his life of Gandhi could easily be read as an ultimately critical one, however judiciously and carefully constructed. After all, in spite of his name being linked with the struggle for freedom in South Africa, Gandhi had practically no contact with Africa or its people. His campaign against “untouchability” in India had limited success even within his own family and circle. The new constitution did make “untouchability” illegal and did provide a system of “reserved” places for untouchables—in schools, colleges, and government jobs—but this has led periodically to heated debate and violent clashes with those who consider such advantages unfair. The traditional attitude has not vanished and the living conditions for the very poor and for many manual workers have not improved much since Gandhi’s lifetime.

Most grievously, Gandhi could not halt Hindu–Muslim antagonism; it morphed into India–Pakistan hostility, which has led to several wars and enduring suspicion between India and Pakistan. Lelyveld describes in detail Gandhi’s inability to build productive relationships with other leaders like Jinnah and Ambedkar, while little is said of the happy and successful collaboration with others, for example with Nehru.

One might think that Gandhi’s legacy on the whole has been depicted negatively and yet there is no denying Lelyveld’s deep sympathy with the man. The picture that emerges is of someone intensely human, with all the defects and weaknesses that suggests, but also a visionary with a profound social conscience and courage who gave the world a model for nonviolent revolution that is still inspiring. It was a model for revolution both on the vast political level and on the personal and domestic one: nothing was unimportant in Gandhi’s eyes, and nothing impossible. He set an almost impossibly high standard and struggled personally to meet it. So if it is all seen as ending in tragedy, it was, Lelyveld writes,

not because he was assassinated, nor because his noblest qualities inflamed the hatred in his killer’s heart. The tragic element is that he was ultimately forced, like Lear, to see the limits of his ambition to remake his world.

This Issue

April 28, 2011