Retirement was not usually a concept of pressing concern to Chinese emperors. Succession and survival were normally quite enough to keep them occupied, and death—when it came—was often unexpected and frequently brutal. But Emperor Qianlong, who reigned from 1736 to 1795 CE, was unusual in his willingness to plan for his own future on a more than basic scale. The factors affecting his thinking about retirement seem to have been fourfold. Firstly, he would not reign longer than the sixty-one years on the throne that had been his celebrated grandfather Kangxi’s astonishing achievement, and was the longest single reign in the whole of Chinese history. Qianlong would be willing to abdicate rather than seem to challenge his grandfather’s honorific distinction.

Secondly, Qianlong, despite the glorious natural sites and far-flung estates that were his for the asking in virtually any part of his vast domain, would plan for at least some of his retirement time to be spent within Beijing’s Forbidden City itself, and in a modest location: an awkward sliver of gardens and old buildings bunched in the northeast corner of the walled palace grounds, on a plot of land just 525 feet long and 121 feet wide, which had previously been used to house elderly dowager empresses or female imperial relatives once their husbands had died.

Thirdly, Qianlong made it clear that the aura of his newly conceived imperial retirement home would be scholarly and religious, allowing ample time and facilities for reading, reflection, learned conversation, prayer, and occasional theatrical and musical diversions. Fourthly, the emperor emphasized that every item brought in to decorate the retirement complex must be made to the highest standards of craftsmanship, whether created in the Forbidden City’s manufacturing establishments—which were numerous and filled with able artisans eager to do the emperor’s bidding—or sent in as gifts from imperial appointees in the provinces or by the wealthy Chinese scholar-aesthetes and merchants whose elegant estates in the Yangzi River region Qianlong loved to visit on the imperial southern tours that were one of the signatures of his reign.

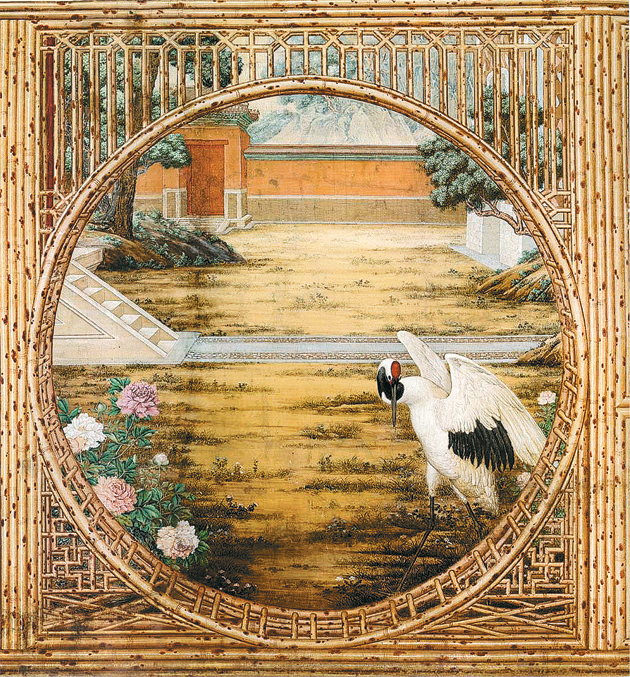

These highest standards would apply to all objects, regardless of cost, material, or function: to jades and inkstones; cloisonné and calligraphy; porcelain and ornamental tiles; lattice screens and window frames; ornamental rocks and flowering plants; paintings on glass and glazing on bricks; lacquered pillars and embroidered silk cushions; carpets and window shades; altar hangings and sutra cases; tables, day beds, and benches; incense burners and stools. And since Qianlong had always thought of himself as a potent family man whose concerns for his own elder relatives, children, and consorts could not be surpassed, the constant bustle of family life—with toddlers and growing children absorbed in their games and exploring their own little universes, yet bringing no unseemly noise to mar the emperor’s rest—was invoked by trompe l’oeil scenes in many of the buildings, to surprise and beguile him. Crossing a landing, reaching for a book, pushing a door that had been left ajar, the emperor might find that he was only viewing a scene within a scene: reality and the imagination fused together, down to the wisteria blossoms dangling from a trellis outside a painted window, or by long-legged cranes searching for painted insects in their painted garden.

This mini palace garden retreat is now being meticulously restored in China, in part with state funding, in part with foundation grants and generous support from the World Monuments Fund. The lustrous and learned catalog of selected items from Qianlong’s retirement home, now on view at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art after a prior stint at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, offers a rare opportunity to see such a range of the decorative arts of late imperial China. The objects chosen for the two exhibitions are somewhat different in the two venues, with some additions and subtractions that partly reflect space limitations and partly the desire to display some of the American museums’ own relevant works. But the basic premise of the show is that as the restoration proceeds, heavier construction in some sections of the imperial garden has meant that a selection of their contents—some ninety items in all—are currently available for travel rather than being stored away till all the work is completed. Once all construction and repair is finished—the current anticipated deadline is in 2019—these objects will be returned to their earlier homes, perhaps never to travel again.

The catalog also points out to viewers that while around fifty of the objects on display are from the retirement palace itself, close to another forty of them are not in fact from it, although they could have been. In other words they have been chosen from other palaces in the Forbidden City to fill in some of the gaps.

Advertisement

We may harbor feelings about the heaviness and overelaboration of Qing decorative arts, and about the contrasts one might draw between these objects—with their elaborate inlays and trompe l’oeil diversions—and the unsurpassed elegance and grace of objects and furnishings from the earlier Ming dynasty (1368–1644 CE). But there is no doubt that this exhibition will get us as close to the court sensibilities of the Qianlong era as we are ever likely to be. It reminds us, too, that Qianlong was not born into a Chinese family, and that as a descendant of the Manchu warriors from the north who had overthrown the Ming he might well have had more eclectic aesthetic standards than the earlier Ming rulers.

How much did all this cost Qianlong? We will never know exactly, but it must have been a great deal, even though many objects were “gifts” within the various versions of that ever flexible word. We learn from the catalog, for example, that one way Qianlong sought to control costs was by having little models made of wood, paper, and glue prepared to scale, with miniature versions of the probable decorative motifs included. They were then dispatched to the various workshops, and to wealthy officials, so they could gauge the exact proportions and coloring of the spaces and fabrics that might be the most effective.

Other costs were doubtless met by the emperor’s Imperial Household Department, the nei-wu-fu, which was so structured that its imperially appointed personnel funneled large sums from salt and textile manufactories, and from the major trade centers, directly into the emperor’s own coffers. This money was available for any private projects the emperor might choose.

Much, perhaps most, of the restoration work, new construction, and procurement—as Nancy Berliner tells us in her three finely researched chapters of the catalog—was completed during the 1770s. This was a period in which Qianlong had successfully brought an end to the deficits run up by his grandfather, but had not yet begun a series of badly commanded and financially disastrous military adventures both within China and on its borders, which brought the treasury back to a more dire level.

At one point in her narrative Berliner pauses to discuss the 1782 suicide by a senior official who had been intensely corrupt at the same time that he acted as a procurer of elaborate Buddhist screens for the emperor’s retirement garden, and comments that “the emperor never noted down any thoughts he may have had regarding the possibility that ill-gotten money had created the treasure that now graced his spiritual spaces.”

Very recently, as it happens, Chinese scholars have been exploring the newly located archives of a shadowy office known as the Secret Accounts Bureau. This secret bureau helped the emperor to levy the euphemistically named “penitence silver” that officials were compelled to pay directly into the imperial coffers when they were accused—or even just suspected—of major corruption or official malfeasance. The amounts of money paid to the emperor through such secret channels were close to five million ounces of silver, of which almost three million can be traced to deposits in the emperor’s own accounts in the Imperial Household Department.* As these huge sums poured into Beijing they were largely unassigned to specific financial categories, and often graced with no more comments than the emperor’s terse “noted.”

Whether Qianlong bent the rules or one always approves of his taste, there is no doubt that he was a considerable connoisseur, and it was during his reign that the imperial art collection in China was reorganized: provenance of works was traced, dating was reassessed, major gaps were filled—by purchase or pressure—and massive, carefully edited catalogs were compiled and published. However morally dubious some of his sources of revenue might have been, and however crooked some of his protégés may have been, the emperor could still be a man of his word.

So when it became clear that he was almost certainly going to reign longer than his famous grandfather, Qianlong did indeed abdicate the throne in 1795—during his sixtieth year of rule—thus leaving intact Kangxi’s record as the longest-ruling monarch in China’s recorded history. But though Qianlong formally abdicated, as promised, he continued to actively supervise the government of his newly promoted son, and kept a tight hold over policy-making until he eventually died in 1799, just a year and a half shy of his ninetieth birthday. Despite all the care, expense, and energy that had gone into the formation of his idealized retirement garden, Qianlong spent little time there during his four retirement years, and after his death the gardens and pavilions gradually faded from their brief period of glory.

Advertisement

None of the six Qing dynasty emperors who ruled after Qianlong were significant connoisseurs, nor did any of them live long enough to enjoy the pleasures of the retirement garden; but despite their lack of concern the garden continued to receive gifts of artworks and furnishings, as is proven by the evidence in the palace account books unearthed in the Forbidden City archives, a selection of which are translated in the exhibition catalog. The Qing dynasty collapsed in 1912, and after staying on in the Forbidden City for a dozen years the last emperor was forced out by local military forces in 1924.

While parts of the Forbidden City, and some of the artworks, were opened to the public and to tourists at that time, the retirement complex fell into general neglect. The current wide-scale interest in the restoration of the northeast corner of the Forbidden City comes swiftly after the equally careful rebuilding of another palace and courtyard area in the northwest corner, which had been destroyed by fire just after the end of the dynasty, but was reopened to the public with considerable fanfare a few years ago.

Though there have been so many unpredictable upheavals in China over the last century, the world of Chinese fine arts has begun to display some curious continuities with the earlier Qing world. Such thoughts are prompted by the recent exhibition of works by a current generation of Chinese artists at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and the publication of a thoughtful and evocative catalog entitled Fresh Ink: Ten Takes on Chinese Tradition, edited by Hao Sheng, the museum’s curator of Chinese art. This was a comparatively small exhibition, but its interest and its current significance spring from the way that the works in the show were selected and created. As Hao Sheng explains, in 2006 the museum identified ten current Chinese artists whose work they particularly admired—some resident in the United States, some in China, and some moving with apparent ease and confidence between the two countries, as whim and financial necessity dictated—and asked each of them to select a work from the museum’s own Chinese art collections that engaged them in some special way, and to use that engagement as a springboard for their own emotions in order to produce new work.

Not surprisingly the process of identification and adaptation varied with each artist, but by 2010 each of the ten had met the challenge in their own particular way. As Hao Sheng explains in the catalog, the exhibition “Fresh Ink”

presents art inspired by other art, recognizing that artists have always worked both with and against the traditions they inherit. This is particularly true in China, where engaging the past has been a central part of every artist’s education and a starting point for artistic creation. It is, in fact, a cornerstone of Chinese culture that the past is a basis of authority and a place for validation.

Even after they had made their choices, the ten artists were free to pursue them in whatever direction they chose, and to tackle them from whatever angle they found most fruitful. Some changed their minds in the middle of the process, if they felt constricted—and one was sidetracked by his discovery of Jackson Pollock. But as finally completed and assembled for the exhibition, the ten works revealed a kind of commonality, choosing stylistic avenues that would have made sense in earlier periods of Chinese culture, as well as to twenty-first-century post-revolutionary Chinese sensibilities. Though some borders inevitably overlapped or defied definition by genre, one could see that four of the artists chose to explore landscape, three focused on figure painting, one chose to reconsider Ming dynasty decorative techniques, and two chose to explore the genre of Chinese writing, whether represented originally in rock or in bronze.

Without pushing the point too far, one can see how some of Qianlong’s standards would have been met in these works. Obviously, this would have been clearest in the landscapes, where the current renderings of the world of nature comfortably made their peace with the past. One of those who chose landscape tied his work to the eleventh-century CE “northern Song” tradition of powerful vertical scrolls; another chose the horizontal scroll form, striving for the kind of harmonies between humans and natural landscape detailing; a third—who had been so struck by Jackson Pollock—sought to discover if certain aspects of Pollock’s works could be linked to the forms of Chinese landscape.

But it was only the fourth of the artists exploring landscape, Xu Bing (born in China in 1955), who chose to launch an attack on the whole way that landscape had been routinized and rendered banal. Xu Bing’s response was to take a series of images from China’s most celebrated painting self-help volume—the Mustard Seed Garden Manual of 1679, which for centuries had been used to teach budding artists how to render the basic forms of trees and plants, cattle and birds, rivers and mountains, scholars and artisans, and all the other stocks-in-trade of the traditionalists—and then to cut and paste these selected images from the manual and the accompanying explanatory text into a separate giant scroll, by means of which images and texts that had no relation to each other or to reality were juxtaposed into an apparently coherent but in fact chaotic and indecipherable montage that made nonsense of any attempt at order.

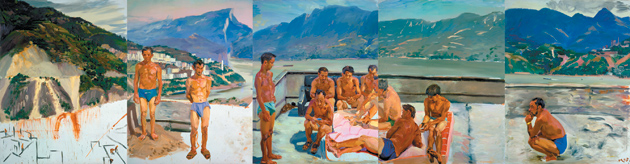

The three artists who chose to work on figure painting had their own methods for taking a basic genre and transforming it into something both modern and unfamiliar. Yu Hong, born in 1966, and the only woman artist in the group of ten, chose as her springboard a well-known painting, attributed to a twelfth-century emperor, of court women preparing silk. By creating a series of eight banners on which she painted the figures of a number of young women she had worked with or photographed, she gave a new presentation of the idea of women’s work, but at the same time made the original painting a small part of her larger vision. The second figure painter, Liu Xiaodong, born in 1963, chose a number of volunteers from students in Boston high schools he had visited during 2008, and used their tough-guy attitudes and street clothes to conjure an image of the violence that was likely to occur in their lives ahead, after they left their current sheltered worlds. (Unlike the other painters, Liu used acrylic and charcoal rather than ink to get the gritty effect that he sought.)

The third of the figure painters was Li Jin (born 1958), who was the only one of the three to assault the genre that Qianlong had used as the decorative mode in his retirement garden. Li took as his initial guiding image the familiar scenario of “the elegant gatherings of scholars” that had been celebrated for close to two millennia in China by countless painters, poets, and essayists, as an idealized form of literati life and the shared joys of the scholarly mystique.

Li Jin boldly took this overlay of images and thrust them rudely into the early twenty-first century, but with all decorum gone, the once-revered scholars paunchy now, with wispy hair and straggling beards, their flushed faces sodden with drink, sprawled naked in hot tubs with barely clothed women companions or comatose fellow philosophers, gazing mournfully at the piles of food and bottles for which they have no more room. “A vision of a tradition run amok,” we might say, and hardly designed to bring solace to an aging denizen of a retirement palace. And if we look carefully at the images, we might note the personal computer clutched by one of the scholars while his less with-it colleague strives to keep his calligraphy steady on the page.

Qianlong’s world had been, among its many other attributes, a place for order and for classification. He himself helped to write the rules for the ordering of his collections, just as he tried to determine authenticity among conflicting claims. His retirement garden was, in this sense, an experimental zone for quality control, just one quiet corner of an expanding empire. The challenge lay in the inquiring eye and the retentive mind, and in the differences in scale that came more easily once the underpinnings were clear. In their turn, the ten artists featured in “Fresh Ink” represent only a tiny step toward thinking about the wider artistic world they represented.

Perhaps the most useful guide to China’s multilayered modern art worlds can be found in the careful source book Contemporary Chinese Art: Primary Documents by the University of Chicago professor and curator Wu Hung. In this detailed synopsis and catalog Wu succeeds in creating a broad series of definitions we can use to bring order to our own thoughts and to any recent Chinese works we may encounter. Broadly, Wu suggests a three-way subdivision, starting with the period from 1976 to 1989 (i.e., from Mao’s death to Tiananmen), proceeding through an initial period of globalization from 1990 to 2000, and ending in our current “coda” to a new millennium. Breaking these subdivisions into manageable smaller categories is not easy, but Wu Hung suggests that we can bunch certain types of growth and change into pretty clear groupings: the phase of unofficial art groups; the debates over “formal beauty,” realist painting, and “scar art, which restaged tragic moments of the Cultural Revolution”; contemplative painting; growth of an avant-garde; absurdity and irrationality; political pop and video art; art for the marketplace; the role of the Shanghai Biennale of the year 2000; and the tensions between quoting and plagiarism.

Most of the book is composed of firsthand essays and reflections on China and an artist’s role within it. It is intriguing, for example, to trace the growth of Xu Bing’s views on art before he did his personalized rendition of the Mustard Seed Garden for the exhibition “Fresh Ink.” As early as 1989 Xu Bing was writing:

Nowadays the art world has become an arena. What do I want from it? Handing one’s work to society is just like driving living animals into a slaughterhouse. The work no longer belongs to me…. I hope to depart from it, looking for something different in a quiet place.

Xu also wrote powerfully about the years he spent creating his invented Chinese and English calligraphic writing texts, A Book from the Sky, based in part on lessons and practice he received during his enforced transfer to the countryside as the son of a “Black Party gangster,” but that led him to prefer his own privately created writing systems to those in use in the “real” world. His private words, he wrote in 1999, “treat every person equally; they do not engage in any sort of ‘cultural bias,’ since no one, not even I, is able to read them.” His made-up words, Xu added, “are like viruses inside a computer: they intercept the part of the brain that people are used to using.”

Adding spice to the long passages of firsthand reflections on the Chinese art scene, Wu Hung has added detailed and fascinating data on the rise of prices within the modern Chinese art market. The first major leap upward occurred around the year 2000, and was reflected in the fantastic increase in gallery space and auction companies. Sotheby’s and Christie’s earned $22 million in Asian contemporary art in 2004, which jumped to $190 million by 2006. The total of five galleries in Shanghai and Beijing dealing in contemporary Chinese art in the year 2000 had in the same two cities become three hundred by 2008. Liu Xiaodong, one of the “Fresh Ink” artists mentioned above, set a new record for a domestic painting sale in 2007 of $8.2 million. Biennales were held in most major cities, lawsuits proliferated, and the constant tussling between galleries and government led to a dizzy progression of enforced closures.

However high the prices rose for contemporary art, one fact might have brought some peace to Qianlong’s shade: the highest price for any Chinese work of art in the new century—$69.5 million—was not for the holders of current fame, but for an elaborately decorated blue and yellow vase, only sixteen inches high, sold by an obscure English auction house to a mainland China bidder. The exact provenance of the vase is not known, but apparently it had been taken, at an unknown period, from one of Qianlong’s palaces.

This Issue

April 28, 2011

-

*

See Ting Zhang, “‘Penitence Silver’ and the Politics of Punishment in the Qianlong Reign (1736–1796),” Late Imperial China, Vol. 31, No. 2 (December 2010). ↩