God engages me through women. My task has always been to bring women to God.

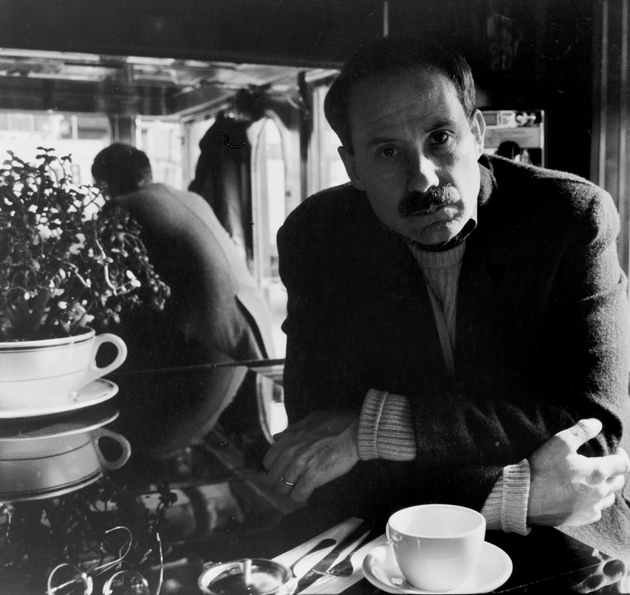

—James Ellroy

James Ellroy is, he tells us, “lurchlike big and unkempt.” He’s a “dirty-minded child with a religious streak”—his first “booze blackout” is at age nine. He “brain-screens” and “scopes out” girls and soon after “stalks” and “side-tails” them. He’s a lonely misfit child who lives to “read, brood, peep, stalk, skulk and fantasize,” in the grip of a “kiddie-noir predation.” After his parents “split the sheets” in 1955, he and his “bunco-artist,” “Hollywood Bottom-Feeder” dad with the “sixteen-inch schlong” live together not in an apartment in Santa Monica but in a “pad.” His dad makes of him a “co-defiler” of his mother: “His mantra was, She’s a drunk and a whore.”

Even before his mother, Jean Hilliker Ellroy—“pale skin and red hair, center-parted”—is raped and strangled in 1958 and her murderer never identified, he’s fixated on the female as The Other and has succumbed to The Curse: “I hated [my mother] because I wanted her in unspeakable ways.” He’s a loiterer, a voyeur, a “pious Protestant boy” whose gaze is drawn to “any and all nearby women.” In adolescence his hormones “hosanna” and he becomes a compulsive burglar—a “B&E artiste”—who leaves no clues behind and is never caught. As once he’d sat in his beautiful red- haired mother’s clothes closet and inhaled the smell of her lingerie and nurse’s uniforms, so in the homes of schoolgirls of his acquaintance he lies “on Their beds…[runs] his nose over Their pillows…[steals] sets of lingerie.” After high school he’s “psych-discharged from three months in the army.”

He becomes a Benzedrine addict: “cotton wads soaked in an amphetamine-based solution,” “an ever-tapable source of jack-off sex.” He veers “very close to psychosis”—“I twitched, lurched and betrayed my mental state”—until at age twenty-nine in August 1977 he begins attending AA meetings and quits “booze, weed and pharmaceutical uppers” as well as “shoplifting and breaking into houses.” He becomes a “tenuously reformed pervert, adrift,” convinced that he has discovered God’s mission for him: “to write books and find The Other.”

But this is a brief respite. The sex fantasy is “endlessly repetitive and easily transferred.” In the throes of his pursuit of The Other—“her, her, her or Her?”—the hypersexed and hyperventilating narrator of The Hilliker Curse soon reverts to his default-perve self: lurks in bookstores near the UCLA campus, returns to L.A. haunts where he continues to peep, skulk, stalk, and generally pursue women with the passionate intensity of a visionary, or a serial killer in the making. An obsession with Beethoven—“Beethoven was the only artist in history to rival the unknown and unpublished Ellroy”—leads him to stake out the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, where, after concerts,

women with violins and cellos scooted out rear exits…. Single women walked out, lugging heavy instruments. I offered to help several of them. They all said no.

The identification with Beethoven isn’t merely aesthetic but something more primal: Beethoven

was a fellow brooder, nose picker and ball scratcher. He yearned for women in silent solitude. His soul volume ran at my shrieking decibel. You and me, kid:

Her, She, The Immortal Beloved/ The Other. Conjunction, communion, consecration and the com- pletion of the whole. The human race advanced and all souls salved as two souls unite. The sacred merging of art and sex to touch God.

It is Beethoven who would have understood Ellroy’s “deep loneliness and sorrow…. I often played the adagio of the Hammerklavier Sonata before I went peeping. Beethoven approved more than condemned the practice.” Years later, nearing sixty, in the throes of yet another love of “cosmic dimensions,” Ellroy claims without irony: “I’m Beethoven with the late quartets and his hearing restored.” And it is Beethoven who supplies the epigraph for Ellroy’s unfettered and uncensored autobiographical essay: “I will take Fate by the throat.”

Since F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Crack-Up (1936), with its blunt, bold, unflinching, and revolutionary candor—“ten years this side of forty-nine, I suddenly realized that I had prematurely cracked”—American writers have been scouring their devastated selves. The long reign of American confessional poets—Robert Lowell, W.D. Snodgrass, Anne Sexton, John Berryman, Sylvia Plath—attests to the wide-ranging ambition and ver- satility of the subgenre. In The Hilliker Curse Ellroy never mentions Norman Mailer, whose quasi-prophetic, Lawrentian utterings in The Prisoner of Sex (1971) and elsewhere closely resemble his own “loony language loops” and “Ellroyized” prose in the service of endless self-mythologizing: “Faith and self-will clash and fuel me…. Asceticism and lust clash and fuel me”: “So women will love me. So I get what I want. There is no other truth.”

Advertisement

Like Mailer, Ellroy imagines himself in heroic thrall to a “self-created and speciously defined” myth of sexual captivity and transcendence—the conviction “that I have always possessed an unfathomable fate.” For both Mailer and Ellroy, the male “fate” is inconceivable without a female component, or complement—The Other. (The archaic term “muse” seems to have been retired. But fundamental to this way of thinking is Robert Graves’s notorious remark: “A woman is a muse or she is nothing.”) A self-styled radical in politics, Mailer was astonishingly conservative, even primitive in his thinking about women and sex, while Ellroy, self-declared “racist-provocateur” and admirer of Ronald Reagan, is unexpectedly liberal, even feminist, in his thinking about women and sex: “I’m a matriarchalist now.”

Ellroy doesn’t speak of himself in the third person, as Mailer did in some of his more flamboyant personal essays, but he shares Mailer’s penchant for bombast and mysticism, the rhapsodic identification with a transcendent self: “My nerves continued to crackle at history’s mad pace”; “I was a man of devout faith.” (Faith in what, precisely? Ellroy is never more than jokey about his vaguely delineated “pious Protestant” background that never seems to interfere with his sex fantasy–driven life.) In startling contrast to the jazzy diction of his typical speech is a solemn oracular voice, its essential looniness disguised by the quasi-visionary language:

There’s a world we can’t see. It exists separately and concurrently with the real world. You enter this world by the offering of prayer and incantation. You live in this world wholly within your mind. You dispel the real world through mental discipline. You rebuff the real world through your enforced mental will. Your interior world will give you what you want and what you need to survive.

And:

I possess prophetic powers. Their composition: extreme single-mindedness, superhuman persistence and the ability to ignore intrusions inflicted by the real world. I believe in invisibility. It is a conscious by-product of my practical Christianity, honed by years spent alone in the dark.

In this intense inner world of women “summoned in dreams” to the accompaniment of Beethoven’s music, Ellroy is not hesitant to acknowledge that “I masturbated myself bloody.”

The Hilliker Curse is a sequel of sorts to My Dark Places: An L.A. Crime Memoir (1996), Ellroy’s account of his impassioned though ultimately futile investigation into the death of Jean Hilliker, undertaken with the assistance of a retired Los Angeles County homicide detective named Bill Stoner, and also his fascination with the famous Black Dahlia case of 1947: the murder, dismemberment, and “body dump” of a beautiful young Hollywood model and aspiring starlet named Elizabeth Short.

Going through the police file, more than thirty-five years after his mother’s death, Ellroy learns a plethora of details about her life, many of them demeaning and sordid, including the fact that her partially undressed body was found by the roadside in El Monte, California, close by a high school playing field, with her nylon stocking and a cotton cord lashed around her neck—“a classic late-night body dump.” After a desultory police investigation the case was abandoned, unsolved, just as the Elizabeth Short case was eventually abandoned, unsolved, to be resurrected in Ellroy’s The Black Dahlia of 1987, the first novel of his acclaimed L.A. Quartet.

My Dark Places is a brilliantly imagined and executed memoir, far more engaging than The Hilliker Curse since its subject isn’t the author’s unbridled “symphonic romanticism” but the 1958 murder case of a woman whom Ellroy scarcely knew, and its language is less jazzily histrionic and oracular. Where the tone of The Hilliker Curse is manic, the tone of My Dark Places is calmly elegiac:

A cheap Saturday night took you down. You died stupidly and harshly and without the means to hold your own life dear….

Your death defines my life. I want to find the love we never had and explicate it in your name.

I want to take your secrets public. I want to burn down the distance between us.

And at the conclusion of what has been an exhaustive, grinding, and failed mission, My Dark Places is a declaration of love:

I’m with you now. You ran and hid and I found you.

Your secrets were not safe with me. You earned my devotion. You paid for it in public disclosure.

I robbed your grave. I revealed you. I showed you in shameful moments. I learned things about you. Everything I learned made me love you more dearly….

You’re gone and I want more of you.

It’s questionable whether The Hilliker Curse is even partially comprehensible if one has not read My Dark Places. Certainly one could not intuit the significance of the lost Jean Hilliker for Ellroy from his sometimes glib allusions to her in the new memoir; nor could one guess at the powerful emotions evoked on virtually every page, and in particular those passages concerned with the child Ellroy in thrall to fantasies of the Black Dahlia—“my symbiotic stand-in for Geneva Hilliker Ellroy.” Where The Hilliker Curse is a stand-up monologue of the “dirty-minded child with a religious streak”—at times not unlike the performance of a carnival geek whose sole, terrible trick is to bite off the head of a live chicken for the titillation of an abased crowd—My Dark Places is a profound and pitiless exploration of the origins of obsession, to the point at which obsession shades into near psychosis:

Advertisement

My nightmares had a pure raw force. Vivid details burst out of my unconscious…. I saw [Elizabeth Short, whose dumped body had been surgically bisected at the waist]…spread-eagled on a medical gurney.

Tho se scenes made me afraid to sleep. My nightmares came steadily or at unpredictable intervals. Daytime flashes complemented them.

I’d be sitting in school. I’d be bored and prey to odd mental wanderings. I’d see entrails stuffed in a bowl and torture gadgets poised for business.

I did not willfully conjure the images. They seemed to spring from somewhere beyond my volition.

Yet in The Hilliker Curse Ellroy is critical of My Dark Places as “fraudulent and dramatically expedient.” His effort at “play[ing] detective and [framing] my mother within book pages” has come to seem in retrospect dishonest:

All our work got us nowhere. We lived the dead-end/unsolved-crime metaphysic. I brooded in the dark with Rachmaninoff and Prokofiev. The music described romanticism’s descent into twentieth-century horror. It complemented my psychic state. I knew we’d never find the killer. I took copious notes on my emerging mental relationship with my mother. I understood that the force of my memoir would derive from a depiction of that inner journey. I erred in that regard. I knew that reconciliation was the only proper ending as I signed my book contract. I learned very little about Jean Hilliker’s death. I gained considerable knowledge about her life and structured my revelations in a salaciously self-serving manner.

(As if salaciously self-serving isn’t the very soul of American noir!)

But The Hilliker Curse takes for granted the reader’s knowledge of the violent and sordid murder case that is the primary material of My Dark Places, and the basis of Ellroy’s obsessions; the new book’s focus on the ever-shifting yet repetitive emotional consequences of the murder comes to seem, at about the midpoint of the book, formulaic and predictable, as if Ellroy had invented a narrative rife with Freudian-Oedipal significance to explain his obsessive fixation upon women, in the way that, for instance, William March “explains” the psychopathic behavior of his little-girl villain in The Bad Seed (1954)—evil is inherited genetically. Where in My Dark Places this material was painfully raw, fresh, and unassimilated, now in The Hilliker Curse it has become overfamiliar as a sort of “dead mom” shtick. There’s a measure of self-loathing amid Ellroy’s braggadocio in his depiction of a bookstore appearance:

The lectern was raised, the room was packed, I had a slay-the- audience view….

I read from My Dark Places….

May 28, ’04…. The six-thousandth public performance of my dead-mother act.

I was boffo. I read from pitch-perfect memory and laid down even eye contact. I had a pulpit and an eons-deep Protestant bloodline. I was the predatory preacher prowling for prey….

A Q&A session followed. Two hundred sociologists—a dead-mom-tour first. A man asked me how I stage-managed grief.

(The boffo performance nets a willing woman—Ellroy’s next overwhelmingly passionate, if temporary infatuation.)

Both My Dark Places and The Hilliker Curse cover periods of time in James Ellroy’s life when he was enormously productive and inspired—writing the L.A. Quartet (The Black Dahlia, The Big Nowhere, L.A. Confidential, and White Jazz) and the Underworld USA Trilogy (American Tabloid, The Cold Six Thousand, Blood’s a Rover), by any measure among the most ambitious and accomplished crime fiction in the history of American literature—despite the impression the memoirs give of a personality alternately brooding and frantic and continually about to implode or vaporize. Until Ellroy, no one had seriously and extensively explored the mystery-detective genre as a means of reimagining history, in this case the links between organized crime and political corruption in Los Angeles in the 1950s (the L.A. Quartet) and more generally in the United States from the late 1950s to the early 1970s (the Underworld USA Trilogy).*

Certainly, no one had experimented with the essential structure and language of the traditional noir novel, a hybrid of romance and hard-boiled urban realism as conventional as a sonnet, as practiced by Raymond Chandler and imitated endlessly thereafter. Ellroy’s distinctive “telegraphic” prose style, first developed in The Big Nowhere as a practical means of cutting the overlong manuscript by one quarter, is coldly rebarbative but brilliantly suited to his unsentimental subject. Of the very long sequel to American Tabloid, The Cold Six Thousand, Ellroy describes in The Hilliker Curse how he’d charted a “super-planetary” design for this deeply pessimistic overview of the 1960s:

My pace was Herculean. My focus was Draculean…. I read research briefs and compiled notes. The outline ran 345 pages. I foresaw a 1,000-page manuscript and a 700-page hardback.

America: four years, five months and 17 days of wild shit. Two hundred characters. Comparatively few women and a reduced romantic arc. An abbreviated style that would force readers to inject the book at my own breathless rate.

I wanted to create a work of art both enormous and coldly perfect. I wanted my standard passion to sizzle in the margins and diminish into typeface. I wanted readers to know that I was superior to all other writers and that I was in command of my claustrophobically compartmentalized and free-falling life.

A casualty of Ellroy’s twin obsessions at this time—with the writing of this original and demanding prose fiction and with his compulsive communion with fantasy incarnations of, among others, the Swedish mezzo-soprano Anne Sofie von Otter and the dead poet Anne Sexton—was Ellroy’s second marriage. His wife sensed his fantasy infidelities and, reading the manuscript of the book, pronounced it “overlong, overplotted, and reader un-friendly. She said it was jittery and frayed and approximated my spiritual state.”

Not one to undersell his talents, Ellroy has said, in an interview in The New York Times, that he is “the greatest crime novelist who ever lived. I am to the crime novel in specific what Tolstoy is to the Russian novel and what Beethoven is to music”—though he might more accurately have aligned his work with the scale and range of Balzac’s Human Comedy, the obsessive intensity of Simenon’s crime novels, the stylistic eccentricities and unremitting misanthropy of Louis-Ferdinand Céline. No Tolstoy, as he is no Henry James, Ellroy more plausibly resembles an American approximation of Dostoevsky in such works as Notes from Underground and the breathlessly paced Crime and Punishment; the sprawling, intermittently feverish, and leaden The Possessed with its crowded cast of characters has affinities with Ellroy—to some readers, sheer genius; to others, unreadable. His more immediate forebears in the United States include Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, and Ross MacDonald—each of whom would have been appalled by Ellroy’s postmodernist variants on the traditional mystery-detective form—as well as Hunter S. Thompson, Jack Kerouac, and William Burroughs. Add Mickey Spillane’s detective Mike Hammer: “chick magnet and a Commie-snuff artiste.”

When its author isn’t charting oracular, visionary heights, The Hilliker Curse is often very funny. Ellroy is a master of what might be called noir-by-daylight: his jived-up loony language demystifies the aura of dread and fate usually associated with the genre. Instead of “saw” there is “eyeballed” or “eyeball-strafed”; there’s the mock stutter of “furious führer and furtive fantasist,” “pile on the pianissimo and postpone the pizzazz,” “I was resurrection-razzed and chaliced by chastity,” “love-starved and full of shit,” “I was frayed, fraught, french-fried and frazzled.” Ellroy is wonderfully dyspeptic, as unyielding as Mark Twain would have been on the nightmare mega-book-tour of five European countries and thirty-two US cities, consecutively:

Spring in Roma—who gives a shit? My publisher booked me a boss hotel suite…. I pulled the curtains and anchored them with heavy chairs. I had an epiphany and began reading the Gideon Bible placed in the nightstand drawer.

I got halfway through the Old Testament. Cancer cells started eating at me….

Amsterdam in spring?—Truly Shitsville. Pot fumes wafting out of coffeehouse doorways and horseflies turd-bombing canals.

Midway in the mega-tour, while The Cold Six Thousand ascends best-seller lists, Ellroy fantasizes “cancer-cell migration,” collapses “in slow motion [onto] a silk-brocade bed,” quits, and returns home to the long-suffering Helen, who is “all love” though soon to be embittered by her loss of status as what Ellroy calls The Other, in a diminished role as “crazy man’s nurse…depleted and furious.”

This wife, Ellroy’s second, the woman with whom he remains the longest—fourteen heroic years!—calls her husband “Zoo Animal” and “Big Dog,” and herself the “Zoo Animal’s Keeper.” She is identified as Helen Knode, a writer; apart from deserving the Patient Griselda Award as the most martyred of writer’s wives, she is capable of some vivid wordplay herself, as in this sudden, revealing outburst to Ellroy in the fall of 2003:

You drove around Carmel in shit-stained trousers. My friends heard you jacking off upstairs. You were vile to my family. You peeped women while you walked Dudley [their dog]. You went to a network pitch meeting, bombed. You’d dribbled ice cream on your shirt. An executive asked you to describe your TV pilot. You said it was about cops rousting fags and jigs. You ran your car off the 101 and came home bloody…. You became someone else as I watched helplessly and came to hate myself and doubt my own sanity for having stayed with you.

Ellroy and Helen are divorced on April 20. Ellroy and a new Other, named Joan—“The most stunning woman I had ever seen“—plan to be married on May 13. However, within a few pages, Joan departs. “She ran”—before the wedding.

Soon Karen arrives.

“Do you really believe that you conjured me?”

I said, “Yes. I do.”

“You saw me in a dream and put me in a book.”

“That’s correct…. I saw you quite clearly.”

“And you weren’t at all surprised when you met me twenty-odd years later?”

“No. Prophecy is a by-product of my extreme single-mindedness and the cultivation of solitude.”

Though Ellroy is deeply in love with this new incarnation of The Other—that is, Karen, married and the mother of two young daughters—he is unable to persuade her to “divorce her fruit husband” and marry him.

She’d say, “You don’t understand family. All you’ve got is your audience and your prey.”

It’s to Ellroy’s credit that he includes such quietly uttered observations—like flashes of lightning in a devastated landscape that seem to pass by him unremarked, but make perfect sense to the reader.

Soon Karen departs, replaced by another “new woman,” Erika—an L.A. writer, married and with two daughters—whom Los Angeles acquaintances characterize as an “opportunist.” However, Erika looks “startlingly like Jean Hilliker” and soon ascends to the status of The Other: “She possessed a heroic soul. She was Beethovian in her schizy grasp at life in all its horror and beauty.” At the time of the writing of The Hilliker Curse, Ellroy and Erika are still together: “Yes, baby. You’re absolutely right. This is the sweetest shit that’s ever been.” One lover notes “our cosmic dimensions” but “stops short of crediting God.” In the memoir’s concluding pages, which exude an air of having been hastily written, Ellroy declares:

I reject this woman as anything less than God’s greatest gift to me. I address her with the faith of a lifelong believer…. She is an alchemist’s casting of Jean Hilliker and something much more. She commands me to step out of the dark and into the light.

Buoyed by its manic tempo for the first 150 pages, The Hilliker Curse gradually loses momentum as the author’s voice begins to repeat itself, and the conjured women, for all that they excite the besotted Ellroy to exalted praise, blur into one another. The Hilliker Curse is finally less about singular individuals than about the chilling power of obsession, as the most rhapsodic love alliances come to seem, to the neutral observer, but variants of folie à deux. For as the memoirist has said, the sex fantasy is “endlessly repetitive and easily transferred.”

This Issue

April 28, 2011

-

*

Ellroy is the inspiration for his fellow crime writer Michael Connelly’s Los Angeles homicide detective Hieronymus Bosch, a moody and sometimes violently inclined man whose mother, when he was a child, was brutally raped and murdered, and her assailant was never identified. Connelly’s Harry Bosch series—sixteen novels beginning with The Black Echo (1992); the most recent is The Reversal (2010)—ranks among the very best police procedurals in contemporary fiction and, like Ellroy’s more sprawling and more densely plotted novels, aspires to cultural significance far beyond the usual range of the genre. ↩