We may dream that our attics hold treasure but usually the dusty rooftop spaces are crammed only with cobwebs. Bill Bryson, however, chasing “the source of a slow but mysterious drip” in the old Victorian rectory where he lives, came face to face with a hidden door. This led out onto a tiny flat space between the roof gables, but since this was in Norfolk, one of the flattest counties of eastern England, the small platform offered wide panoramas and misty views. And the peaceful-looking farmland he was gazing at, an archaeologist friend told him, concealed its own treasures: Neolithic tools, Bronze Age graves, Roman coins, Viking farmsteads, all slowly turned up by the plow.

Bryson’s new book, At Home, also looks outward from a small domestic space, revealing vistas of history and uncovering strange finds. As he guides us around his rambling house he delves into the background of home life from the Stone Age to today, telling the story of inventions and introducing a gallery of characters from kings and queens to scullery maids. In the hands of a less playful writer a history of the home might progress staidly through the different rooms, with a potted history of cooking in the kitchen, conversation in the drawing room, and so on. Bryson does follow this route up to a point, incorporating brisk histories of sex, marriage, illness, and medicine in chapters on particular rooms, with a brief excursion into the garden, reminding us in passing how reliant middle- and upper-class home owners were on their hard-worked and ill-paid servants. So far, so conventional. But Bryson’s house of history is full of surprises.

Take the study, the obvious place for a sober account of reading and scholarship at home. The chapter opens thus:

In 1897, a young ironmonger in Leeds named James Henry Atkinson took a small piece of wood, some stiff wire, and not much else, and created one of the great contraptions of history: the mousetrap.

Bryson’s rectory study, it turns out, is so dark and cold that it discourages lingering: “Almost the only reason we go in there now is to check the mousetraps.”

This leads to a long account, complete with an illustration of the patent drawing for Atkinson’s “Little Nipper,” on the relationship between humans and mice. We are drenched in a waterfall of information. The domestic mouse is so adaptable that it can live in a refrigerated meat locker at–10 degrees Celsius; adult mice can squeeze through tiny openings three eighths of an inch wide; a female can start breeding at six to eight weeks and give birth monthly thereafter; in 1917 every surface in the Australian town of Lascelles was coated with furry creatures, and “over fifteen hundred tons of mice—perhaps a hundred million individuals” were killed before the invasion was over.

From mice Bryson sallies on to rats and plague, minuscule pests like head lice and bedbugs and the microscopic creatures humans share their lives with: “vast tribes of isopods, pleopods, endopodites, myriapods, chilopods, pauropods, and other all-but-invisible specks.” After a hair-raising discussion of germs, the chapter turns to bats, before concluding with the locust swarms that devastated the American West and Canadian plains in the 1870s. Not quite what one would expect in a study.

Before At Home, Bryson had written A Short History of Nearly Everything (2003), a lively, prize-winning history of the sciences. As he says, after trying to understand the universe and how it is put together, “the idea of dealing with something as neatly bounded and cozily finite as an old rectory in an English village had obvious attractions. Here was a book I could do in carpet slippers.” Instead, he discovered that a house is a sprawling repository, a virtual archive: houses “are where history ends up.”

Given the potential scope, he claims to have been “painfully selective,” although indulgence often seems to outweigh pain. The pace is relentless and the tone jumps from glee to inky gloom. Reading the book at one stretch is like being pinned down by a domestic Ancient Mariner dressed as a butler with a wild glint in his eye. The chronology is hazy and the text leaps between periods: examples from the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries may be cited in a single paragraph as if they were coexistent. Bryson relishes lists and throws statistics around like confetti, and the lack of notes makes it impossible to find the sources of his information, or to judge its reliability. There has been a vogue in recent years for “bottom-up” history based on the experience of “ordinary” people, as opposed to the grand narrative of public events: books and television programs on households in different periods; on aspects of physical life, like noise or cleanliness; on single commodities such as salt, porcelain, cod, nutmeg. Bryson has pored over these, as his bibliography shows, seizing magpie-like on sparkling anecdotes. He is generous in crediting particular sources in the text, but the glittering nest he weaves is all his own—and the result is hugely enjoyable.

Advertisement

Bryson can find some justification for the twists and turns of the narrative web in the curious layout and early history of the rectory itself. It was designed around 1850 by a provincial architect called Edward Tull for a young clergyman, Thomas Marsham, and the plan had its oddities: Tull placed the entrance at the side and a water closet on the staircase landing, blocking out all light on the stairs, and he sketched in a dressing room with no connecting door to the bedroom. Marsham sensibly altered these, but made some strange decisions of his own, like taking over the servant’s hall to enlarge his dining room, thus leaving his three servants—Miss Worm, the housekeeper; Martha Seely, the underservant; and the groom and gardener James Baker—with nowhere to relax apart from the tiny kitchen and scullery. Marsham’s vocation lets Bryson expatiate on the income and idleness of country rectors and on their manifold extracurricular achievements, from the Reverend Jack Russell, who bred terriers, to Thomas Bayes, who devised “Bayes’s theorem,” a way of working out inverse probabilities. The theorem had no practical application in his own day, but is now, we are told, used in “modeling climate change, predicting the behavior of stock markets, fixing radiocarbon dates,” and other knotty problems.

Much of the book is concerned with the slow realization of ways life can change, and be improved. The date of the rectory provides another happy starting point. It was completed in 1851, the year of the Great Exhibition, allowing Bryson to open his narrative not with a vernacular building, but with the Crystal Palace, Joseph Paxton’s miraculous glass dome in London’s Hyde Park. Paxton’s feat was made possible by the use of standard parts like cast-iron frames, by technological innovations like sheet glass, and by economic perks like the abolition of the British window tax and glass tax.

But within the exhibition the starring display was the United States section, which was full of inventions such as sewing machines, reapers, and Colt’s repeat-action revolver. The exhibition proved that American machines could “stamp out nails, cut stone, mold candles—but with a neatness, dispatch, and tireless reliability that left other nations blinking.” The US section—this “outpost of wizardry and wonder”—almost didn’t make it to the show, since Congress refused to pay the cost of transport, and privately raised funds brought it to the London docks but no further. In the end it was bailed out by the American philanthropist George Peabody, living in London, who provided emergency funds to bring it to Hyde Park, erect it, and man it for five months.

Like Peabody, Bryson is an American living in Britain. This too contributes to the book’s vantage point. Born in Des Moines, Iowa, he traveled around Europe as a student in the early 1970s, working in Britain and marrying his English wife before returning briefly to the United States to finish his degree. He settled in England in 1977 and became a full-time writer only in the late 1980s, after a career in journalism that included senior posts for The Times and The Independent.

In 1995 Bryson and his family moved back to live in New Hampshire for eight years, during which time he published his very funny account of a trek along the Appalachian Trail, A Walk in the Woods (1998), and the comico-serious I’m a Stranger Here Myself: Notes on Returning to America After Twenty Years Away (1999). But to British readers like myself, the key work is Notes from a Small Island (1995), which neatly summed up our national quirks. Brits have warmed to Bryson’s mix of humor, affection, and generous campaigning zeal, and now claim him as a British institution, “our American.” He inhabits the role well. After the success of A Short History of Nearly Everything, he joined with the Royal Society of Chemistry in founding an annual prize for science writing in schools. Not only is he chancellor of Durham University, but in 2007 he became president of the venerable Campaign to Protect Rural England, which has been lobbying to save the British countryside and its way of life since 1926.

From the beginning of his publishing career, Bryson’s subjects have alternated between the United States and Europe, with a brief excursion to Australia with In a Sunburned Country (2000). At Home reflects this double heritage, drawing examples from both sides of the Atlantic. This makes the reader look afresh at national habits, whether the American emphasis on labor-saving conveniences (stemming from the relative lack of household servants), or the use of ice in drinks. In the chapter “The Kitchen,” this transatlantic tale is told with Bryson’s habitual brio:

Advertisement

In the summer of 1844, the Wenham Lake Ice Company—named for a lake in Massachusetts—took premises in the Strand in London, and there each day placed a fresh block of ice in the window.

Crowds gathered; Thackeray mentioned Wenham ice in a novel; Queen Victoria placed an order. The infrastructure of warehousing, shipping, and marketing was developed by the vain, difficult Bostonian Frederic Tudor, building on the technological genius of his quiet colleague Nathaniel Wyeth. But although American ice traveled from Boston to Bombay, the greatest fans turned out to be Americans themselves. Diners in Manhattan supped on pumpernickel rye and asparagus ice cream while Chicago “became the epicenter of the railway industry in part because it could generate and keep huge quantities of ice.” The one market the Americans did not capture was the British: by the 1850s most ice used in Britain was from Norway, where suppliers cashed in by quietly changing the name of a lake near Oslo to “Lake Wenham.”

Apparent digressions, like the account of the ice trade or the history of whaling in connection with sperm-oil lamps, and the scattered serendipitous details, like the fact that the son of the narrow-minded public-health expert Edwin Chadwick “devised the score-card, box score, batting average, earned run average, and many of the other statistical intricacies on which baseball enthusiasts dote,” are not entirely wayward. Indeed they demonstrate the serious nature of Bryson’s underlying thesis. If we question the evolution of any room or trivial object, he suggests, we will uncover stories laden with social, economic, political, and even religious implications. When we switch on a light, for example, we might stop to imagine what life was like when the only illumination was from rushlights or candles. How did people put up with smoky gas lamps or risky kerosene flames—responsible for up to six thousand deaths a year in America in the 1870s? The detours into these subjects are integral to our understanding.

Often the history of things we take for granted stretches far back through time. The chapter “The Dressing Room” opens with the discovery in an Austrian glacier in 1991 of a freeze-dried, fully dressed, prehistoric hunter, cheerily named Ötzi by the locals. And when Bryson asks “how long people have been dressing themselves,” we are taken back 40,000 years to the Cro-Magnons and their invention of string, which could be twisted into ropes, fishing lines, and, of course, textiles. The tale then leaps millennia to the use of flax and hemp, the medieval working of wool, the growth of the silk trade, and the elaborate sumptuary laws that decreed dress for each social class.

Similarly, the story of the bathroom reveals that far from ancient peoples being mired in dirt, as some historians have suggested, the Minoans had running water and bathtubs, the Greeks scrubbed up after working out naked in the gymnasium, while one house at Pompeii had thirty taps. “Roman baths,” we learn, “had libraries, shops, exercise rooms, barbers, beauticians, tennis courts, snack bars, and brothels.” By contrast, the early Christians equated godliness not with cleanliness but with grime—a rejection of the material world.

The most fundamental question—when humans first developed a sense of “home”—cannot be answered. As an example, however, Bryson turns to the ancient settlement of Skara Brae, on the Scottish Orkney Islands, which was uncovered in a storm in 1850, just when his Norfolk rectory was being built. Skara Brae’s village of circular stone dwellings is older than the Pyramids and Stonehenge, yet it is recognizably “domestic,” with drainage systems, storage alcoves, covered passageways, and even damp exterior water courses to keep the inside dry.

The “Neolithic Revolution”—the beginning of farming and the building of cities, from China to the Amazon basin, New Guinea to West Africa—happened across the globe between 11,500 and 5,000 years ago: a relatively short time span on the scale of human evolution. But far from creating a lifestyle better than that of nomadic hunter-gatherers, settled agrarian life brought poorer diets, more disease, and earlier mortality—which remain our legacy. “Out of thirty thousand types of edible plants thought to exist on Earth,” writes Bryson, “just eleven—corn, rice, wheat, potatoes, cassava, sorghum, millet, beans, barley, rye, and oats—account for 93 percent of all that humans eat, and every one of them was first cultivated by our Neolithic ancestors.” The animals raised for food today are those that they domesticated. “We may sprinkle our dishes with bay leaves and chopped fennel, but underneath it all is Stone Age food. And when we get sick, it is Stone Age diseases we suffer.”

The skilled construction of Skara Brae provides an apt beginning, as Bryson is clearly enamored of everything to do with the materials, design, and techniques of building. Architects and ambitious house owners abound in this book, particularly passionate individuals working on a large scale, like John Vanbrugh at Castle Howard and William Beckford at Fonthill Abbey, Jefferson at Monticello and Washington at Mount Vernon, or Addison Mizner in Palm Beach. Bryson delights too in technical detail, whether he is describing the different types of cottages built in medieval England, regional variations in the notched corners of log cabins—“V notch, saddle notch, diamond notch, square notch, full dovetail, half dovetail, and so on”—or the anchoring of the Eiffel Tower’s iron framework. He pours forth statistics, like the consumption of oak in early modern Britain: a fifteenth-century farmhouse contained the wood of 330 trees; Nelson’s Victory consumed 3,000; the eighteenth-century charcoal industry devoured 540 square miles of woodland per year.

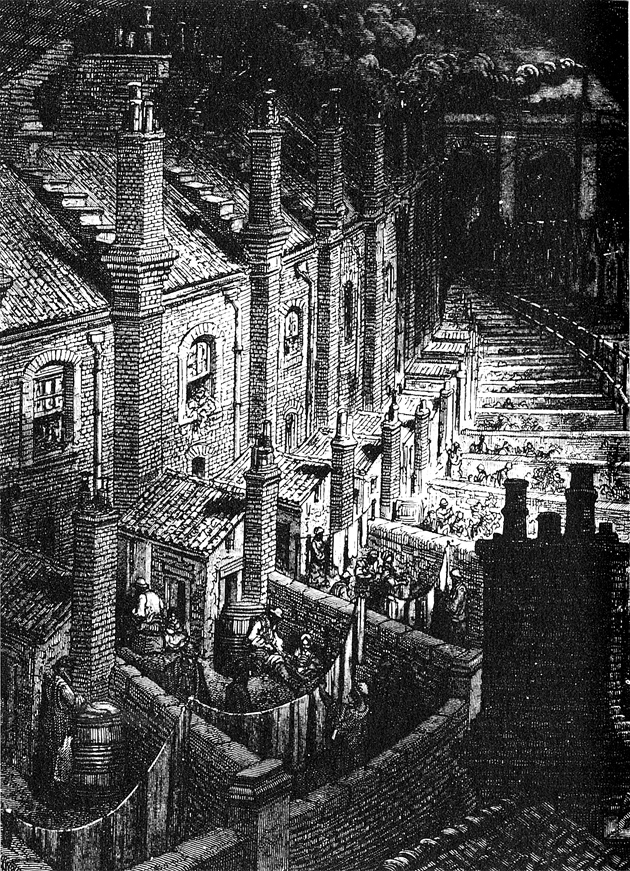

In particular, he waxes lyrical about the British use of brick in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, before it was overtaken by changing fashions and slowed down by the fierce brick tax imposed to pay for the American war in 1784. Brick’s revival in the mid-nineteenth century was prompted by three factors: the invention of a more efficient new kiln, the expansion of the cities, and the removal of the tax in 1850. The result was the spread of terraces and suburbs of uniform color and style, “mile after mile of ‘dreary repetitious mediocrity’ in Disraeli’s bleak description.”

There is nothing dreary about At Home. Each ordinary house, it seems, is built with the bricks of history. “The Hall,” now reduced to a mere entrance passage, is a feeble relic of the great medieval hall-dwellings with their central hearth open to the sky. The development of practical, fireproof chimneys in the fourteenth century spelled the end of communal domestic life: the roof beams could now be covered and an “upstairs” created, a new realm of privacy. A procession of inventors and entrepreneurs has contributed to our modern home lives. Some have won global fame, like Mrs. Beeton, whose rapidly compiled Book of Household Management features hilariously in “The Kitchen,” or Thomas Edison, whose career is switched on in “The Fuse Box.” But Bryson also mentions those who miss global fame, like Joseph Swan, who is recognized as an inventor but not as the pioneer of electric light, despite the fact that he illuminated his own home “well ahead of anything Edison was able to achieve.”

One pleasure of this book is the respect accorded to lesser-known men and women: Canvass White, who hunted down the secrets of hydraulic cement to line the Erie Canal; Eleanor Coade, whose artificial stone—a kind of ceramic—adorned grand buildings across London; William Blauvelt, who designed the classic telephone dial in 1917; and Edwin Beard Budding, inventor of the cylinder lawnmower (and later of the monkey wrench).

The book’s real heroes, however, are those who tackle squalor and disease. Two such men are celebrated in “The Bathroom.” One is John Snow, who in 1854 worked out through careful use of local maps and death statistics that the cholera in London’s Soho was spread by polluted water. The second is Joseph Bazalgette, who worked “around the corner from Snow, though the two men never met.” In 1858, thanks, ironically, to the enthusiastic adoption of the new flush toilet and the subsequent deluge of waste into tunnels designed only for rainwater, London’s sewers became blocked. A heat wave then plunged the city into “the Great Stink,” causing panic in Parliament and a demand for the sewers to be rebuilt. Bazalgette was the young engineer who took up the challenge, succeeding so well that his system is only now being overhauled. The sewers, filled with evil sludge, make us confront the unwelcome aspects of home life.

At Home has plenty of dark moments and at times, indeed, it verges on becoming a Gothic House of Horrors. Bryson describes death, disease, and disasters with graphic zest, from Fanny Burney’s chilling account of her mastectomy to the statistics of falling downstairs and the sad catalog of childhood deaths listed in thirteenth- and fourteenth-century coroners’ rolls for London: “‘drowned in a pit,’ ‘bitten by sow,’ ‘fell into pan of hot water,’ ‘hit by cart-wheel,’ ‘fell into tin of hot mash,’ and ‘trampled in crowd.'” The most reflective and moving chapter in the whole book is “The Nursery,” where birth and death meet.

I would hesitate to call At Home an authoritative history, but that is not its intention: serious-minded readers can use the wide-ranging bibliography to search further. Instead it is a personal compendium of fascinating facts, suggesting how the history of houses and domesticity has shaped our lives, language, and ideas. The “private life” it describes is swept into an exuberant, shared social history. And as Bryson says in his account of the rooftop view of village and fields, “it is always quietly thrilling to find yourself looking at a world you know well but have never seen from such an angle before.”

This Issue

May 12, 2011