1.

Changing attitudes toward historically inspired architecture, and Classicism in particular, have led to reassessments of buildings that were long dismissed by proponents of the Modern Movement as retrogressive, but which now are widely regarded as advanced despite their traditional appearance. There is no better example of this reversal of posthumous fortune than New York’s Pennsylvania Station of 1905–1910, still keenly mourned as the lost masterpiece of Charles Follen McKim, one of the triumvirate—along with William Rutherford Mead and Stanford White—who gave their surnames to McKim, Mead & White, the most prolific and celebrated high-style American architectural practice during the half-century between the Civil War and World War I.

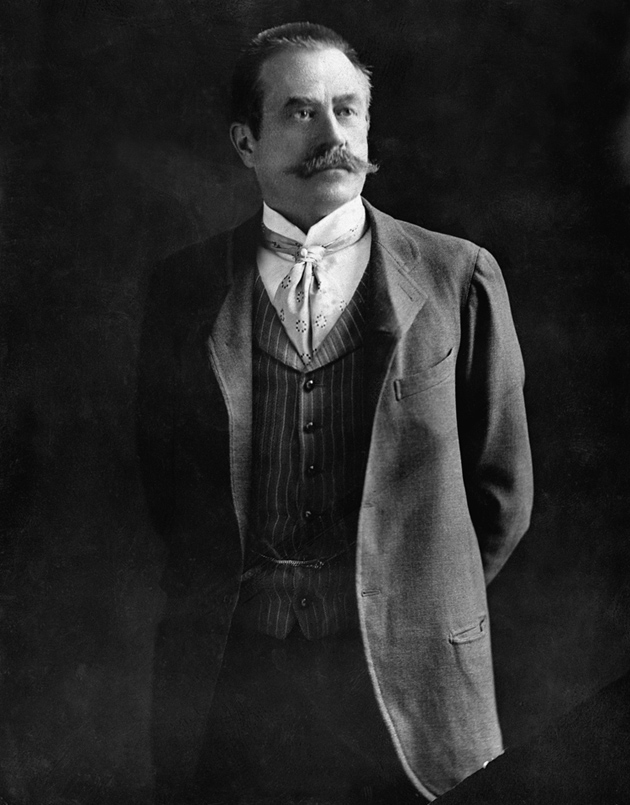

H. Armstrong Roberts/ClassicStock/Everett Collection

New York City’s Pennsylvania Station, designed by Charles Follen McKim of the architectural firm McKim, Mead & White. Modeled on Imperial Rome’s Baths of Caracalla and completed in 1910, it was demolished in the early 1960s to make way for the new Madison

It had long been commonplace to emphasize McKim, Mead & White’s dependence on Old World prototypes. For example, White based his Renaissance Revival New York Herald Building of 1890–1895, which fronted what is still called Herald Square, on Fra Giovanni Giocondo’s Palazzo del Consiglio of 1476–1492 in Verona, and modeled the Mozarabic tower of his Madison Square Garden of 1887–1891 (once the third-tallest structure in the city, after the Brooklyn Bridge and the Statue of Liberty) on the Giralda of 1184–1198 in Seville. Similarly, McKim’s Beaux Arts–inspired Boston Public Library of 1888–1892 owes an obvious debt to Henri Labrouste’s Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève of 1843–1851 in Paris, whereas his Pennsylvania Station followed a conjectural reconstruction of Imperial Rome’s Baths of Caracalla of 212–216 AD.

Though McKim, Mead & White’s historical eclecticism almost never attains the quality of its sources and sometimes appears little more than a skillfully executed precursor of the touristic landmarks we now see replicated at Las Vegas theme hotels, the best of the firm’s work, however derivative in outward expression, on occasion comes close to that of the foremost American master builder of the generation before them: H.H. Richardson, in whose employ McKim and White first met.

However, despite McKim, Mead & White’s current critical esteem—considerably higher than it was a half-century ago—in order to find the true muscle and sinew of advanced American architecture during the heyday of this arch-establishment partnership we must look instead to the mystically inclined but commercially aware Louis Sullivan, spiritual father of the tall office building, and to his spiritual son, Frank Lloyd Wright, the apostle of organic design derived from the native soil. Their heroic quest for an authentically American architecture set them in diametric opposition to what they saw as the deadening hand of Classicism so powerfully wielded by McKim, Mead & White (however much Sullivan and Wright may have absorbed and subsumed historical models themselves).

The American public was rudely reawakened to the significance of McKim, Mead & White by the demolition of Pennsylvania Station, which began in October 1963 but took nearly three years to accomplish because of the huge building’s extraordinarily solid and deep construction. By the time the vast site was cleared and ready to receive the crowning indignity of Charles Luckman’s ticky-tacky Madison Square Garden, completed in 1968, the historic preservation movement had gathered to prevent comparable acts of cultural vandalism. New York’s only other equivalent landmark, Grand Central Terminal of 1904–1913 (a collaboration between the firms of Reed & Stem and Warren & Wetmore), was spared a similar fate when opponents derailed a disastrous redevelopment scheme by Marcel Breuer for its site during the 1970s thanks to the shameful precedent of Penn Station.

McKim’s design marked a significant departure from earlier railway depots because it was built to accommodate the newly electrified trains of the Pennsylvania Railroad, which freed him from the standard arrangement of a train shed attached to a shelter for ticket sales and passenger waiting areas, all at street level or only somewhat recessed (as was the case at the steam-driven New York Central Railroad’s Grand Central Terminal). Electrified trains emit no noxious fumes, so they could run through tunnels rather than on viaducts or in open trenches and thus remain deep underground once they reached their destinations, which enabled McKim to submerge components that previously needed to be above ground.

The new possibilities provided by electrification afforded McKim the freedom to make his ground plan for Pennsylvania Station a marvel of modern efficiency. In choosing the Baths of Caracalla as his model, the architect found an ideal scheme that allowed him to encompass the entire eight-acre site—which covered two full city blocks from West 33rd to 31st Streets and from Seventh to Eighth Avenues—in one immense but cohesive whole, united by a colossal order of granite columns that formed a monumental colonnade on its principal façade along Seventh Avenue and concealed a porte-cochère driveway that ran along its north flank on 33rd Street. This arrival sequence, which protected travelers from the elements in all seasons, was arranged so that luggage could be conveniently unloaded first and then moved to baggage cars via mechanical conveyors, before passengers were driven on to a final stop situated as close as possible to the departure gates, located below street level.

Advertisement

Although Penn Station’s stupendously grand Waiting Room was decked out with all the elaborate masonry detailing of the Classical copybook, the Concourse—where travelers descended to the train platforms on the level beneath it—dispensed with stone cladding and left the building’s steel supports exposed. With its barrel-vaulted glass-paned ceiling and machine aesthetic, the Concourse resembled Joseph Paxton and Charles Fox’s Crystal Palace of 1850–1851 in London; with its strong vertical development and interplay of light and shadow it also brought to mind Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s Carceri d’invenzione of 1745–1751, etchings of imaginary prisons in which the Venetian architect concocted vertiginous multilayered networks of mysteriously interconnected spaces.

This unexpectedly harmonious synthesis of two divergent and supposedly irreconcilable architectural approaches, the Classical and the industrial, would have been a most instructive object lesson during the architectural style wars that were to rage during the two decades following the scandalous sack of McKim’s marvel. No one saw the dire implications more clearly than an anonymous editorial writer in The New York Times, whose voice sounded, at least, like that of Ada Louise Huxtable, our infallible Cassandra of urbanism:

Any city gets what it admires, will pay for, and, ultimately, deserves. Even when we had Penn Station, we couldn’t afford to keep it clean. We want and deserve tin-can architecture in a tinhorn culture. And we will probably be judged not by the monuments we build but by those we have destroyed.

2.

McKim, Mead, and White began working together in New York City in 1879 when the latter, now the best- remembered of the partners, joined forces with his two older colleagues. Although Mead has sometimes been unfairly characterized as a glorified office manager, or at best a mediator between his two antithetical if extravagantly gifted associates, there is no question, as Mosette Broderick makes clear in her thoroughly researched but discursive and uneven Triumivrate: McKim, Mead & White: Art, Architecture, Scandal, and Class in America’s Gilded Age, that the magnetic (and occasionally mutually repellent) poles of the consortium were McKim and White. (The best one-volume treatment of the firm’s work remains Leland M. Roth’s concise but comprehensive 1983 study, McKim, Mead & White, Architects.)

Broderick neatly demonstrates this dichotomy in her introduction by juxtaposing a pair of contemporaneous, functionally identical, but tellingly different New York City schemes that exemplify the two architects’ respective qualities: McKim’s Low Memorial Library of 1895–1898 at his new campus for Columbia University on Manhattan’s Morningside Heights, and White’s Gould Memorial Library of 1897–1902 at his University Heights branch of New York University in the Bronx (which became Bronx Community College when NYU gave up the property in 1973). Each building serves as the focal point for its academic ensemble, is compact in ground plan, and has a shallow centralized dome and a columned entry portico of Roman derivation, but there the similarities end.

The Columbia library is massive, stolid, sober, devoid of ornamental frippery, and though a bit dull conveys an aura of gravitas thoroughly suited to high-minded intellectual pursuits. On the other hand, White’s uptown NYU library is characteristically lighter in volume and enlivened by sprightly detailing, all of which suggests that a little learning can be a delightful thing.

Like Richardson, McKim studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris and possessed an innately more decorous temperament than White, who had almost no formal training but was such a natural-born designer and quick study that his lack of education would have been betrayed to only the most pedantic of Classical scholars. Instead, it was the far more important differences in personal character between McKim and White that held the seeds of destruction for their architectural dream team.

McKim, Mead, and White made their reputations, at first individually and then in concert, during the 1870s and 1880s with a remarkable series of large wood-frame vacation houses in fashionable resort communities along the Atlantic seaboard, including Elberon, New Jersey; Newport, Rhode Island; Lenox, Massachusetts; Tuxedo Park, New York; and the East End of Long Island (where from 1880 to 1883 White designed the Montauk Association—a group of seven capacious “cottages” with a communal recreation building—on a bluff near the tip of the South Fork, a property laid out by Frederick Law Olmsted, landscape architect of New York’s Central Park of 1858–1873).

The novel domestic format devised by the collaborators stemmed less from American precedents than from vernacular traditions in Normandy and the residential work of their older British contemporary Richard Norman Shaw, who harked back to English rural forms with rambling, irregularly angled, multigabled compositions that seemed to be the accretions of many years, if not several centuries. But whereas Shaw clad his houses in half-timber or slate tiles, McKim, Mead & White used natural-colored wood shingles, which they deployed in varied interlocking textures that the architectural historian Henry-Russell Hitchcock (with whom Broderick studied at NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts) vividly likened to birds’ plumage.

Advertisement

The architectural historian Vincent Scully dubbed this the Shingle Style, and in his classic study The Shingle Style and the Stick Style: Architectural Theory and Design from Richardson to the Origins of Wright (1955) rescued these seminal works from decades of critical oblivion and accorded them a central place in the American canon. To the untutored eye these houses—with their deep wrap-around porches (or “piazzas” in the contemporary parlance), overhanging eaves, cylindrical turrets topped by conical “candlesnuffer” roofs, multiple massive chimneys, and a profusion of gables and dormers—may seem indistinguishable from countless other residences of the well-to-do in every good-sized town in the United States, an indication of how pervasive this format became in the decades between the American Independence Centennial and World War I.

But as Scully and Hitchcock both stressed, McKim, Mead & White’s major innovation was a radical spatial reconception of the domestic interior, which gave their houses a breathtaking expansiveness quite the opposite of typically compartmentalized Victorian residences, in which every room was a veritable world unto itself. Scully gives an even more specifically Jamesian explanation as to why this kind of private exurban refuge met with such an enthusiastic reception among a sensitive segment of America’s moneyed class after the Civil War in one of his most rapturous passages:

Civilized withdrawal from a brutalized society encouraged interminable summer vacations (the real decadence of New England here?) to Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard, and the coasts of Massachusetts and Maine, where the old houses weathered silver, floating like dreams of forever in the cool fogs off the sea.

This sense of genteel social retirement and grand self-sufficiency was most apparent in the spacious living halls the firm designed for a number of their Shingle Style schemes. As with the multifunctional ground-floor reception-and-sitting areas that became popular in mid-nineteenth-century Britain, McKim, Mead & White’s adaptations were focused around a vast hearth (often with an adjacent seating alcove, or inglenook) that infused visitors’ first impression with a welcoming warmth both figurative and literal.

Though usually paneled in dark wood, the typical McKim, Mead & White living hall was well illuminated through broad expanses of multipaned windows, often on two sides of the room, which in many cases gave onto the firm’s signature enveloping verandahs. But there was also a distinctly East Asian feeling, which, as Hitchcock noted, went well beyond the superficial application of Japanesque decorative motifs that became a widespread craze during the zenith of the Aesthetic Movement in the 1880s:

The main rectangular space, of which the shape is emphasized by the ceiling beams and by the abstract geometrical pattern of the floor, seems to flow out in various directions into other rooms and into several bays and nooks; but the actual room-space is sharply defined by a continuous frieze-like member that becomes an open wooden grille above the various openings. There can be little question that the major influence here is from the Japanese interior, but the Japanese interior understood as architecture.

Credit for introducing this continuous flow of space to America is most often given to Wright, whose interest in classical Japanese architecture is well known. But McKim, Mead & White was executing these sweeping proto-modern interiors two decades before Wright went even further with that openness in his celebrated Prairie Houses of 1901 onward, with Le Corbusier and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe taking the concept to its logical culmination in their plan-libre houses of the 1920s.

3.

McKim, Mead & White’s output was enormous, more than a thousand buildings all told, with some three hundred in New York City alone. Among the latter were the Columbia and uptown NYU campuses; the Century, Colony, Freundschaft, Harvard, Metropolitan, Players, and University clubs; high-end commercial work for such luxury goods purveyors as Tiffany and Gorham; several banks; town houses for magnates—the Whitneys and Pulitzers—as well as fellow artists including Louis Comfort Tiffany and Charles Dana Gibson, in addition to country retreats for the plutocratic Astor, Mackay, and Oelrichs families.

Although Stanford White remains among the very few architects whose name is widely recognized among laymen in this country, his urban designs were demonstrably lightweight in comparison to McKim’s. White is perhaps most accurately seen as the John Nash of American urbanism, a facile and pleasure-giving metteur en scène of enchanting set pieces that catch the eye but rarely provide much intellectual substance, as was also the case with the English architect who put his mark on Regency London as indelibly as White did on New York at the height of the Gilded Age, but who often also seems more an ingenious stage designer than a shaper of modern civic life.

All the same, there is no doubt that apparently without exception White’s clients adored what he gave them, as indicated by one instance in which his work proved more mobile than is usual in the static art of architecture. During an 1878 study trip through France with McKim, White photographed the triple-arched portico of St.-Gilles-du-Gard, a Romanesque abbey church of circa 1125–1150 in Provence, which he deemed the best work of European architecture. This served as White’s model for a portal he appended in 1900–1903 to St. Bartholomew’s Church, a Lombardic-Romanesque pastiche of 1870–1872 by James Renwick (best known for New York’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral and Washington’s Smithsonian Institution).

St. Bart’s parishioners grew so fond of White’s limestone frontispiece that when they abandoned Renwick’s building in favor of Bertram Goodhue’s Byzantine Revival sanctuary of 1917–1930 on Park Avenue, they took the narthex along with them and had it incorporated into the congregation’s new home. The resulting palimpsest still imparts an incongruous whiff of hybrid Venetian exoticism to an otherwise dreary corporate stretch of midtown Manhattan.

McKim’s characteristic perfectionism (which contrasted with White’s sometimes slapdash solutions) would never be indulged more fully than by J. Pierpont Morgan, who commissioned him to build the New York private library and gallery of 1903–1906 that late last year emerged, more magnificent than ever, from an exemplary interior restoration by Beyer Blinder Belle. To some extent this respectful refurbishment compensates for the affront imposed by Renzo Piano’s unfortunate addition of 2000–2006, the most objectionable aspect of which was its repositioning of the beloved institution’s main entrance from East 36th Street to a new and corporate-looking façade on Madison Avenue, a shift that reduced McKim’s regal vestibule—one of the finest entry spaces in the United States—to a vestigial backdoor appendage.

Morgan’s commission yielded an exceptionally restrained single-story white marble Classical pavilion, its façade centered by a graceful Palladian archway. “I want a gem,” Morgan told the architect, and he got one, though not before spending a small fortune on specifications of almost manic exactitude.

During a visit to the Acropolis in Athens, McKim became fascinated by the ancient anathyrosis technique of assembling precision-ground blocks of masonry without mortar (a refinement the Incas later mastered and employed in their famous walls at Cuzco). Climatic differences would not permit an exact duplication of the Greek assemblage, but McKim came very close by adding a thin layer of lead between the Morgan Library’s marble blocks to compensate for expansion and contraction caused by New York’s more extreme temperatures. This nicety, which J.P. Morgan instantly assented to, set him back an extra $50,000 (about $1.2 million in current value).

4.

McKim is the closest America has ever come to having a national architect, and his imprint on the city of Washington is still palpable on both the urban and the domestic scale. He was a member of the Senate-appointed panel responsible for the so-called McMillan Plan of 1901 (named for the Michigan legislator who sponsored it), which sought to restore order to the capital city’s original 1791 design by the French-born civil engineer and architect Pierre Charles L’Enfant. That grandiose Baroque layout, with radial principal boulevards superimposed on an overall grid of lesser streets, had been only sketchily realized when the federal government moved to Washington from Philadelphia in 1800.

Over the next century, L’Enfant’s scheme was repeatedly compromised, no more so than with the imposition of an undulating Romantic landscape devised in 1851 by Andrew Jackson Downing to surround Renwick’s neo-Gothic Smithsonian of 1846–1855. This visual non sequitur encroached onto the broad greensward L’Enfant hoped would extend westward from the Capitol building to the Potomac. The far-reaching remedial proposals set forth under McKim’s supervision, which were largely but not fully implemented, reasserted the French architect’s intentions, especially in the creation of the National Mall, the strong outlines and verdant integrity of which remain intact as the precinct now considered America’s sacrosanct front yard.

McKim’s strong hand in reshaping the nation’s capital can be seen most frequently in television broadcasts from the White House, where the main floor of the Executive Mansion—especially the East Room, scene of many presidential press conferences; the Cross Hall, through which the president passes to face the cameras; and the State Dining Room, where foreign heads of state are entertained—were all redesigned by him as part of a thoroughgoing renovation ordered by Theodore Roosevelt in 1902. A century after James Hoban’s President’s House of 1792–1800 was first occupied, the neoclassical character of the original structure had been sadly undermined. The exterior was overburdened by a chaotic jumble of greenhouses appended to the west side of the mansion (where the executive office wing now stands), and Victorian interior accretions were aptly likened to the gaudy, overstuffed décor of a Mississippi riverboat.

McKim stripped away the excesses, but rather than going back to Hoban’s delicate interior detailing (which he had covered over but was ripped out in the gut reconstruction of 1948–1952 decreed by Harry Truman) the architect substituted a beefier Anglo-Classical aesthetic that at the time passed for the then-popular Colonial Revival style. Here is yet another example of the inevitable tendency of Classical revivals to reflect the moment of their creation, in this case the nascent imperial ambitions of America in the days of the Great White Fleet.

Only four years after that incomparably prestigious project, McKim, Mead & White’s glory years came to an abrupt and bloody end. White had always been the most assertively, even aggressively, “artistic” of the partners. He amassed objets d’art, antique furniture, and decorative bric-a-brac as compulsively as his younger contemporary William Randolph Hearst, though lacking a tycoon’s resources the architect was forced into a sideline as a sub-rosa dealer to defray the crushing debts he accrued.

A social animal to the bone, White never let his family—conveniently rusticated at Box Hill, the idyllic Shingle Style home on Long Island he built and constantly remodeled for them between 1884 and 1906—interfere with his frenetic social life in the city, which he rationalized as a means of getting jobs from the nabobs of finance and industry. Never has there been a more adept architectural networker than Stanny White, who moved with intuitive ease among the various subsets of New York’s economic and social elite as he made friends and garnered commissions everywhere he went.

White also had a thing for underage girls, a predilection hardly concealed in the louche theatrical haunts that were no less a part of his strenuous nightly rounds than Manhattan’s most exclusive men’s clubs or expensive restaurants. His predatory habits may not have been much different from the tactics of other stage-door Johnnies, but the forty-eight-year-old letch met his nemesis in the ravishing but snakelike sixteen-year-old chorus girl Evelyn Nesbit, who was being primed for a career as a courtesan by her complaisant mother. Nesbit quickly became a favorite of “art” photographers, including Gertrude Käsebier, and her image was widely circulated on wildly popular picture postcards during the first years of the new century.

The lurid tale of White’s fatal attraction for Nesbit has been told many times before, and given the unedifying nature of their relationship, trashier accounts—such as Paula M. Uruburu’s humid American Eve: Evelyn Nesbit, Stanford White, the Birth of the “It” Girl, and the Crime of the Century (2008)—get closer to the reality than Broderick’s rather prim version of events. This affair was the subject of Richard Fleischer’s 1955 film, The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing, which starred Ray Milland as White and Joan Collins, who at twenty-two was somewhat long in the tooth as Nesbit. The title referred to one of the architect’s favorite erotic pastimes, in which he would position himself beneath a velvet-covered trapeze apparatus in one of his several secret playrooms scattered around the Flatiron district—which he euphemized as his “studios”—in imitation of Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s voyeuristic painting Les Hasards heureux de l’escarpolette (1767–1768), which shows a young gallant peering up the skirts of a young woman oscillating above him.

Briefly put, after having Nesbit’s teeth fixed and taking her virginity, White still had no intention of getting divorced, and the gold-digging girl married the rich but unhinged and sadistic Harry Thaw, who became fixated on the architect’s supposed corruption of little Evelyn (whom Thaw saw fit to horsewhip). The denouement to Thaw’s mad obsession came in 1906 when he gunned down his imagined erotic rival from behind at the roof garden theater White designed at his Madison Square Garden, as the architect watched the finale of a musical trifle called Mamzelle Champagne. White likely and luckily never knew what hit him. The autopsy disclosed that he had nephritis and was unlikely to have lived more than a few months anyway.

The ensuing scandal was enormous, but since White’s weaknesses were well known in the bonhomous circles he frequented, little if any opprobrium attached to his partners, who were models of probity. McKim, a depressive already in failing health and further dispirited by his mercurial but beloved colleague’s fate, died in 1909. Mead carried on until his death, in 1928, but the practice’s output plummeted once his two partners left the stage, though the nominal McKim, Mead & White plodded on until it was absorbed by another firm in 1961.

That precipitous decline is confirmed by the epigonal McKim, Mead & White office’s drab, warehouse-like New York Racquet and Tennis Club of 1916–1919 on Park Avenue, one block but a world away from White’s vivacious, peripatetic portico for St. Bartholomew’s, a contrast that in a single glance explains why this unequal triangle was never again the same without its two most acute coordinates.

This Issue

May 26, 2011