Around 1293, nine years before he was exiled from Florence by one of the city’s warring factions, and some fourteen years before he embarked on his Divine Comedy, Dante collected a number of his early love poems together and told a story—in prose—of how they came into being. Most of the poems have to do with his love for a young woman named Beatrice, who died in 1290 at the age of twenty-four. The prose narrative, written in the first person with a heavy self-editorializing hand, seeks to make retrospective sense of the meaning of Beatrice’s existence, both while she graced the world with her presence and now that she gazes on the face of him qui est per omnia secula benedictus—who is blessed for all eternity—in the Latin words that bring to an end Dante’s Vita Nuova.

The Vita Nuova is one of the strangest vernacular works of the Middle Ages. Its narrative juxtaposes quasi-hallucinatory dreams and visions with pedantic commentary on the poems they generated. It describes how Dante was born into a “new life” thanks to Beatrice, yet it is as much a book about his friendship with his fellow poet Guido Cavalcanti as it is about his love of Beatrice. Dante’s avowed intention is to transcribe the “meaning” (sentenzia) of the events of his new life, yet it ends with the author’s declaration that he lacks the means to speak adequately of Beatrice, thereby acknowledging the failure of his “little book,” as he calls it in his proem, to achieve its objective.

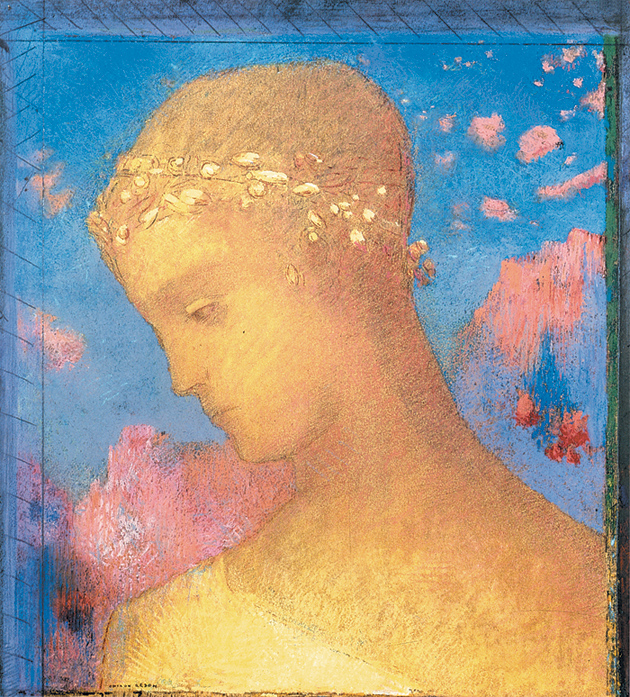

A reasonably accurate translation of the poems is the conditio sine qua non for a proper appreciation of the Vita Nuova, which contains three or four key poems that are crucial to the unfolding of the story as a whole—none more so, perhaps, than the sonnet “Tanto gentile” in section 26, which describes Beatrice at the height of her glory and thus marks the climax of the Vita Nuova. The poem describes her passage through the streets of Florence and the effect her appearance has on those who behold her. Here is the Italian original:

Tanto gentile e tanto onesta pare

La donna mia quand’ella altrui saluta

Ch’ogne lingua deven tremando muta,

E li occhi no l’ardiscon di guardare.

Ella si va, sentendosi laudare,

Benignamente d’umiltà vestuta;

E par che sia una cosa venuta

Da cielo in terra a miracol mostrare.

Mostrasi sì piacente a chi la mira,

Che dà per li occhi una dolcezza al core,

Che ‘ntender no la può chi no la prova;

E par che de la sua labbia si mova

Un spirito soave pien d’amore,

Che va dicendo a l’anima: “Sospira.”

The following is my own strictly literal translation:

So gentle and so candid appears

My lady when she greets others

That every tongue, trembling, goes silent,

And eyes hardly dare to look on her.

She passes by, hearing herself praised,

Benignly dressed in modesty;

And she seems a thing come from

Heaven to earth to show forth a miracle.She shows herself so pleasing to the onlooker

That through the eyes she sends a sweetness to the heart

That cannot be fathomed by whoever has not experienced it;

And it seems that from her lips there moves

A suave spirit full of love

That goes straight to the soul, saying: “Sigh.”

This is one of the most Christological poems of the Vita Nuova, recalling Jesus’ epiphany as he moves through the streets of Jerusalem, dispensing blessings in his wake. Beatrice’s redemptive grace is communicated through her greeting (salute in Dante’s Italian means greeting, health, and, by extension, salvation). She is pure phenomenon: a “thing come/from heaven to earth to show forth a miracle.” The linking of the last word of the eighth verse and first word of the ninth verse emphasizes the word “show” (“a miracol mostrare./Mostrasi sì piacente…”). What appears to the eyes then becomes spiritualized and, as spirit, enters into the onlooker’s inner being, inspiring the soul to emit a sigh. From this sigh of inspiration—this culminating intake and exhalation of breath—the poem we are reading is born.

Little of the essence of this sonnet is conveyed by David R. Slavitt, translator of the new edition of the Vita Nuova:

How modest, how genteel my lady seems

as she strolls, unself-conscious, along the street

intimidating whomever she may meet.

They are mute, as people sometimes are in dreams,

and avert their eyes, as if the dazzling beams

from hers would blind them. Still, it is a sweet

kind of discomfort. It’s hardly a conceit

to say she is angelic for her head gleamsas if with a halo. And radiating from

her person, there is quiet and delight,

inexplicable but undeniable too.

Anyone who has seen her knows it’s true,

and that for an instant all the world seems right.

One sighs in joy as they do in Elysium.

This rendition sins by omission as well as addition. It omits mention of Beatrice’s greeting, salute, around which so much revolves in the Vita Nuova. (Dante had found his “perfect bliss” in her greeting, but when Beatrice chose to deny it to him he fell into a crisis that eventually led to a new style of poetry.) It omits the process of intromission, whereby Beatrice’s presence is incorporated into Dante’s inner self in the mode of spirit. And it omits all references to the heart (a major protagonist of Dante’s Vita Nuova), the lips, and the soul, each of which has precise functions in Dante’s psychology of love. For all these omissions, we are treated to a number of bizarre additions that are not found in the original, such as the references to Elysium, to Beatrice “intimidating whomever she may meet,” and to the halo around her head, to mention just a few.

Advertisement

Such renditions are what you get when you believe that “translation is a vague undertaking.” Slavitt follows up that opening sentence of his “Translator’s Preface” with: “I think of these undertakings of mine as…performances, and also acts of some violence (poems being blindfolded and hustled off to interrogation centers in distant countries).” It is hardly surprising that such “interrogations” often result in disfigurements of Dante’s lyrics.

A few paragraphs later Slavitt uses a different analogy for the relationship between Dante and his translator: “Translating prose, one is the author’s more or less sedulous clerk,” whereas “translating poetry, one is, perforce, his partner.” It is unfortunate that Slavitt subscribes to this notion, for on the whole he does a fine job of translating Dante’s prose. Had the poetry translations been at the level of the prose translations, this would have been a useful and welcome edition of the Vita Nuova indeed—it is handsomely produced, with an excellent introduction by Seth Lerer, one of America’s leading scholars of medieval literature—but Slavitt’s conviction that, when it comes to translation, “liberty and justice are inter- connected” led him to take such liberties with Dante’s poems that he has done an injustice to the edition as a whole.*

One of the reasons I believe that “Tanto gentile” is a pivotal poem is because its exaltation of Beatrice as a Christ figure who embodies a redemptive grace in her person marks a breakthrough in Dante’s struggle to free himself from the overbearing influence of his older friend Guido Cavalcanti, to whom he dedicates the Vita Nuova. Guido was one of the finest lyric poets ever to put pen to paper and Dante’s early lyric poetry was heavily under his spell. In his exquisitely crafted poems, Guido expressed a dark, tragic vision of love. No poet probed more deeply the intimacy of love and death, which the Swiss scholar Denis de Rougemont, in his famous book Love in the Western World (1939), saw as the latent core of the Western myth of romantic love (in several poems Guido puns brilliantly on the root word mor that links amor to morte).

Guido held that love has only an “accidental,” not a substantial, connection with its object, and that overfixation upon the object can lead to various pathologies, including melancholia, ire, and madness. Through a host of personifications of the various faculties of soul, Guido’s poetry dramatizes love as a force of psychic turmoil that mercilessly assaults the lover, causing him to languish, despair, and sigh his life away. If left unchecked, the lover’s sighs will lead to his death.

One of the fascinating aspects of the Vita Nuova is the way it oscillates between such Cavalcantian nihilism and Christian evangelism with respect to Beatrice. The first half of the book describes moments of epiphany that have an adverse effect on Dante, causing him to suffer the malignant symptoms of a good Cavalcantian lover. Dante is dazed and distraught by Beatrice; his vital spirits are thrown into upheaval; and he laments his sbigottimento, his consternation, in terms that pay homage to the aristocratic and charismatic Guido. Clearly one of Dante’s main concerns in the Vita Nuova is to establish his credentials with his “primo amico,” or first friend, as he calls Guido, yet at the same time there is something about Beatrice that, for Dante, makes her more than an accidental object of love. She seems to Dante the quintessential substance of Love itself. In sum, there is a redemptive promise in her presence that militates against Guido’s idea of self-immolating love and passionate despair.

Advertisement

That promise wins the day, if only temporarily, in sections 24 and 26 of the Vita Nuova (the book contains forty-two sections in all). Beatrice’s triumph is most evident in the culminating sigh of the “Tanto gentile” sonnet I quoted earlier. This is not a Cavalcantian sigh through which the lover’s vital substance dissipates away into nothingness. Nor is it the kind emitted by the souls in Dante’s Limbo, in Inferno 4, who sigh in resignation because they live “in desire without hope.” It is a sigh of spiritual infusion, full of prospective hope and new life.

Beatrice’s sudden death, solemnly announced a few sections later in the book, precipitates a much more serious crisis in Dante’s narrative, depriving him of the source of his beatitude (Beatrice means “beatifier” in Italian). For a protracted period of time Dante suffers a relapse, sighing himself away again in the old, morbid way as he grieves over his loss. However, the last poem of the Vita Nuova marks another dramatic breakthrough, as the memory of Beatrice resurges in Dante’s mind. The poem, “Oltre la spera” (Beyond the Sphere), is an astonishing prelude of things to come much later in Dante’s career. It describes a sublime sigh that exits Dante’s heart as a “pilgrim spirit” and journeys beyond the ninth sphere of the heavens, where it beholds the lady who inspired it. When the sigh returns to earth, it speaks to Dante’s heart about its vision of Beatrice. He understands its speech only in part, yet the sigh’s pilgrimage has meanwhile imparted a new, cosmic horizon to Dante’s relation to the girl he first laid eyes on when he was nine years old.

The Vita Nuova comes to an abrupt end in the next section, where Dante declares that, after writing this sonnet, he had a “miraculous vision”—the contents of which he does not disclose—which made him decide to speak no further of Beatrice until he could do so in a more worthy manner. He goes on to say (in Slavitt’s translation): “I am now exerting myself to reach that goal,” expressing the hope “that my life may last a few years more.”

Dante’s life did last a few more years after he wrote those words. In the following decade he went on to write some of his best lyric poems, in particular the four canzoni known as the Rime Petrose (the Stony Rhymes). In 1295 he enrolled in one of the mercantile guilds of Florence, which allowed him to hold public office. In 1300 he was elected to serve as one of the priors of the Florentine Republic. That same year he voted, along with the other priors, to banish the heads of the haughty magnate families that had been perpetuating the violent feud between the White and Black factions of the Florentine Guelph party. One of the people exiled in that decree was Dante’s one-time friend Guido Cavalcanti, from whom he had become estranged a few years earlier, for reasons unknown. In one of his extant sonnets addressed to Dante we find Guido complaining about Dante’s dark moods and the sort of company he was keeping. Be that as it may, Guido’s exile to Sarzana proved to be fatal. Within a few months he contracted malaria and died in August 1300. It is impossible to know how much guilt Dante felt about this outcome; all we know for sure is that Guido’s spirit haunts the Divine Comedy like an unappeased ghost.

Two years later Dante himself would be exiled from Florence after the Black faction, conniving with Pope Boniface VIII, took control of the city. For a while he aligned himself with other Florentine exiles who ineptly plotted an overthrow of the Blacks, yet he soon broke with them in disgust and formed, as he put it, “a party of one.” He spent several years in humiliating poverty, dependent on the charity of patrons in various courts of central and northern Italy. During his first five years of exile he wrote and left unfinished two important treatises—De Vulgari Eloquentia and Convivio. Then sometime around 1307 he suffered what today would be called a clinical depression. He felt he had gone utterly astray, spiritually speaking, as if in a dark wood. Try as he may, he could not move forward. Then something happened, and a way opened up to him. The way took the form of a poem he called the Comedìa, later to be known as the Divina Commedia.

The Commedia is one of the boldest and most improbable undertakings in literary history. It is extremely unlikely that Dante could have pulled it off had he not spent the last twenty years of his life in exile (he died in 1321, shortly after finishing the Paradiso). It is a poem written by a man who finds himself lost in a wilderness. Yet it is equally unlikely that he could have written such a poem had he not also received from Beatrice, while she was alive, a lasting infusion of hope. What saved him in his moment of bewilderment was, among other things, his resistance to despair.

In Canto 2 of the Inferno we learn that Beatrice, descending from Heaven into Limbo, sent Virgil to Dante’s rescue in his moment of danger, as Dante found himself lost in the dark wood of Inferno 1. With Virgil as his guide, the Commedia’s pilgrim undertakes a grim journey through the circles of Hell, followed by an arduous trek up the terraces of the mountain of Purgatory. Virgil takes him as far as the Garden of Eden, where he turns him over to Beatrice, who will be Dante’s guide as they ascend the nine spheres of Heaven. The Beatrice we meet in the Commedia both is, and is not, the Beatrice of the Vita Nuova. The latter was not a fictional character but a real, historically incarnate woman who served as the inspirational basis for the more allegorical character of the Commedia.

It is impossible to say exactly what it was about the living Beatrice that caused Dante to believe that, years after her death, she had played a part in his rescue during the darkest hour of his midlife crisis. Clearly there was more to her than poetic hyperbole, courtly idealization, or what Freud would call overestimation of the erotic object. What makes the Vita Nuova such a singular testament is that, despite its best efforts, it fails to account for the enigma of this mortal woman with whom Dante exchanged only occasional formal greetings while she lived. This failure is one that keeps the Vita Nuova open-ended, projected into future possibilities. It contains within itself the evidence of things unseen and the substance of things hoped for—as in the hope Dante expresses at the end of the book “to say of [Beatrice] what has never been said of any woman.”

This Issue

May 26, 2011