When James Levine’s tangled halo of white hair was picked up by the spotlight shining down over the orchestra pit at the May 9 performance of Die Walküre, at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, the audience roared with pleasure and relief. With good reason. Levine’s bad back and other health woes had forced him to pull out of multiple events he was scheduled to conduct, including one recent performance of this opera, the second in the Ring cycle. But there were no signs of diminished vigor or control on that evening.

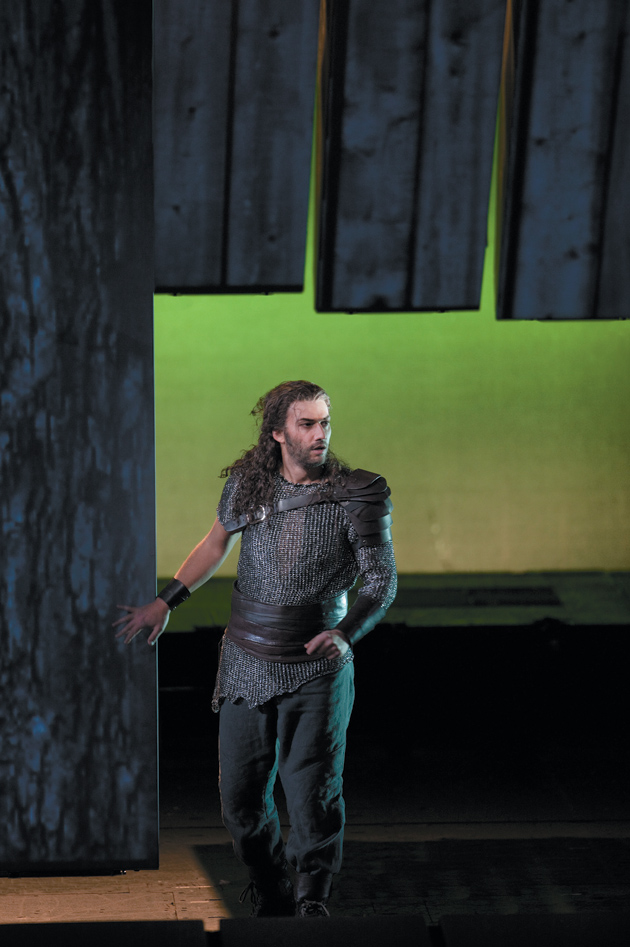

On the contrary, he elicited from the orchestra and the stellar cast an exceptionally rich, nuanced realization of Wagner’s immensely demanding masterpiece. Jonas Kaufmann’s intense, emotionally wrenching Siegmund awakened the passion in Eva-Maria Westbroek’s Sieglinde; Bryn Terfel’s brooding Wotan and Stephanie Blythe’s formidable Fricka, carved as if from a piece of mighty granite, brought utmost conviction to their moral and marital argument; and Deborah Voigt, who on opening night had stumbled and fallen, managed to negotiate the enormous planks of the massive set and utter her wild cries of jubilation and grief. Levine’s mastery—the subtlety, energy, and intelligence of his musicianship—was everywhere in evidence and generated a special current of feeling that seemed to course through the whole house: the feeling of gratitude for a man who had found in himself the strength to conduct so brilliantly and, beyond this, gratitude for the spectacular gifts of the performers, and beyond this still, gratitude for the existence of the work of art itself.

An achievement of this magnitude has a mysterious power to affirm human worth in the face of humanity’s manifest and crushing defects, defects that the composer himself shared in egregiously full measure. I had thought to write something here about Wagner’s vicious anti-Semitism and about the playful attempt by my Wagner-loving Jewish friends to counter its poisonous effects by standing out on the balcony during the intermission and dining on whitefish salad and bagels. In his autobiography, Mein Leben, Wagner himself expressed surprise that many of his most ardent admirers and champions were Jews. But in the charmed space of this particular opera, the space defined by what Wagner termed “deeds of music brought to sight,” the composer’s loathsome personal failings seemed to belong to a different conversation.

Die Walküre is arguably the greatest of Wagner’s works and, with a few other transcendent works such as Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro and Verdi’s Don Carlo, among the greatest of all operas ever written. Figaro and Don Carlo both have a resonating historical dimension: like Shakespeare’s Henriad, they ambitiously situate themselves at the critical juncture between two worlds, one dying, the other struggling to be born. But the ambition of Die Walküre, and the cycle of which it is part, is still greater; it can best be described, I think, as Miltonic. Like Milton, Wagner intended nothing less than to convey in a work of art the very nature of existence—that is, the way things are, what they are, and how they got to be that way. Of course, such an aesthetic design in itself could be merely overweening and risible. What is astonishing about Die Walküre, as about Paradise Lost, is that the artists succeeded, and I propose to tease out a few parallels between their achievements.

Milton and Wagner both undertook to center their attention on the relations between the divine and the human. Of course, Milton did so as a believing Christian: the ancient myth with which he grappled was still current in the seventeenth century, as it is for many today, and he was therefore committed to the project of reconciling the misery, confusion, and cruelty of human existence with an omnipotent, omniscient, and benevolent deity. Wagner had no such commitment. His Wotan and other Germanic gods have no comparable claim on belief, and the artist is not under any obligation to justify their ways. They exist not as metaphysical agents worshiped in the real world but as figures in a work of art, and the artist can convey their words and the musical phrases in which they utter them with mingled awe and irony.

But the difference, significant though it is, is less absolute than it might at first seem. As soon as Milton chose to set his God in motion as a character, as soon as he set out to make the gnomic utterances of the biblical story the stuff of a fully imagined epic, he had embarked, whether he liked or not, on a course of awe and irony comparable to that which brought forth Wagner’s Wotan. It may be possible within the thickets of theology to reconcile the absolute power of a divine maker and the freedom of independent human agents, but in the lived texture of Milton’s poetry the tension between the two becomes unbearable, as here in God’s anticipation of Satan’s success:

Advertisement

And now

Through all restraint broke loose he wings his way

Not far off heaven, in the precincts of light,

Directly towards the new created world,

And man there placed, with purpose to assay

If him by force he can destroy, or worse,

By some false guile pervert; and shall pervert

For man will hearken to his glozing lies,

And easily transgress the sole command,

Sole pledge of his obedience: so will fall,

He and his faithless progeny: whose fault?

Whose but his own? Ingrate, he had of me

All he could have; I made him just and right,

Sufficient to have stood, though free to fall.1

God’s unnerving attempt to avoid blame, his anger at an act that has not yet occurred but that in his omniscience he knows will occur, the slippage from “can” to “shall” to “will,” the terrible pastness-before-the-event of “Sufficient to have stood”—these are the signs not of Milton’s confusion but of his artistic courage, his resolute willingness to enter a space of contradiction and deep disturbance.

Though the conceptual terms are different, there is something of the same courage in Wagner’s depiction of Wotan’s predicament as he contemplates what were once his hopes for his son Siegmund:

Oh where is this free one,

whom I’ve not shielded,

who in brave defiance

is dearest to me?

How can I create one,

who, not through me,

but on his own

can achieve my will?

Oh godly distress!

Sorrowful shame!

With loathing

I can find but myself

in all my hand has created!2

Wotan’s monologue turns the biblical design inside out: now the source of divine pain is not bitter disappointment consequent on the creation of human freedom but the inescapable, nauseating recognition of himself in everything he has made: “Zum Ekel finde ich/ewig nur mich/in allem, was ich erwirke!” Under the extraordinary narrative pressure that Milton and Wagner both bring to bear on the problem of divine power and free will, what emerges is not a philosophical resolution but a strange and anguished voice. The voices of Milton’s God and Wagner’s Wotan share a queasy recognition of the limits of absolute power, and the fascination of their predicament lies as much in constraint and hollowness as in effulgent glory.

The religions of Paradise Lost and of Die Walküre are both centered on sacrifice. Perhaps it is inevitably so: the ancient Roman poet Lucretius said that all religions are cruel and that they almost always entail the sacrifice of children. Milton’s God finds a willing victim in his only begotten son; Wagner’s Wotan encounters more resistance but in the end contrives, in part against his own will, to sacrifice both a son and a daughter. The cost runs highest, of course, for the victims themselves (though Milton was averse to dwelling upon the Crucifixion), but the cost most searingly represented in both works is paid by the divine fathers. It is measured principally in loneliness.

There is a very strange moment in Paradise Lost in which Adam recounts how he came to request the creation of woman. God had brought all of the creatures in the world before Adam to receive from him their names and in doing so to acknowledge their subjection to the superior human. But Adam noticed that something was missing: each of the creatures had a mate (“lion with lioness”) with whom to experience delight. He carefully considered whether he could choose a mate for himself from those already at hand—there was, as Milton may have been aware, a midrashic speculation that Adam actually tried intercourse with all of the other creatures and found the experience unsuitable—but he concluded that “the brute/Cannot be human consort.” Therefore he asks God for a fit mate. God responds with an unnerving set of questions:

What think’st thou then of me, and this my state,

Seem I to thee sufficiently possessed

Of happiness, or not? Who am alone

From all eternity, for none I know

Second to me or like, equal much less.

How have I then with whom to hold converse

Save with the creatures which I made, and those

To me inferior, infinite descents

Beneath what other creatures are to thee?

A few moments later, after an appropriate display of human abasement on Adam’s part, God says in effect that he was just kidding, and he proceeds to create Eve. But for a moment there is a startling glimpse of divine solitariness, or rather of what Wotan describes as a sickening recognition that he can find but himself in everything he has created.

Advertisement

What we are perhaps glimpsing here, in both Milton and Wagner, is a quality peculiar not only to their vision of god but also to their own artistic genius. Mozart and Verdi, like Shakespeare, have characteristic styles, but it could not be justly said of them, I think, that they infuse every character they create with the intense savor of themselves and themselves alone. Milton and Wagner are instances of what Keats, writing about Wordsworth, termed the “egotistical sublime.”

But it is a measure of the greatness of Paradise Lost and of Die Walküre that this quality is turned into an unparalleled analysis of the power of love. In both works, the analysis turns on the devastating experience of loneliness in marriage. Milton, it should be noted, was not only the author of Paradise Lost; he was also the author of The Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce (1643) and several other daring prose works in which he made a compelling case for granting divorce on the grounds of emotional incompatibility.3 Canon law had sanctioned divorce in cases of incurable impotence, but to Milton it was perverse for society to offer relief to someone trapped in a marriage bereft of “carnal performance” and at the same time to ignore the frustrated longings of mind and spirit. Milton was anything but a prude: eschewing the medieval euphemism for marital sex as “paying the debt,” he spoke of the deep pleasure of “voluptuous enjoyment.” But to imagine that sexual intercourse, however pleasureless, was the essence of marriage—better to marry than to burn—seemed to him grotesque:

To grind in the mill of an undelighted and servile copulation must be the only forced work of a Christian marriage, oftimes with such a yoke-fellow, from whom both love and peace, both nature and religion mourns to be separated.

More powerfully than anyone before him, including Shakespeare, Milton conveyed in his divorce tracts a strange form of suffering: loneliness not in a state of radical isolation but in the everyday, continual presence of a spouse. The intensity of the pain may be difficult for those who have not encountered it to grasp, but anyone who has experienced it directly—as Milton himself did with his first wife—will recognize the force of his analysis. A person locked in a bad marriage, he wrote,

lies under a worse condition than the loneliest single life; for in single life the absence and remoteness of a helper might inure him to expect his own comforts out of himself, or to seek with hope; but here the continual sight of his deluded thoughts without cure, must needs be to him…a daily trouble and pain of loss, in some degree like that which reprobates feel.

Small wonder, he noted, that in such a situation the principal feeling toward the unresponsive spouse turns quite simply to hate. Milton fails to acknowledge it, but his spouse must have experienced a reciprocal loathing.

It is this condition—what Milton called “a drooping and disconsolate household captivity, without refuge or redemption”—that Wagner (who had his own personal experience of it) depicts with exceptional sensitivity in the second act of Die Walküre, in the long, painful argument between Wotan and Fricka. The unbearable condition of loneliness inside a marriage is still more explicit in the opera’s first act. The wounded Siegmund—having been injured in an attempt to rescue a maiden who was being forced to marry a man she feared—staggers into Sieglinde’s dwelling and is succored by her. Regaining his strength, he makes haste to leave before the return of Sieglinde’s husband, Hunding: “Ill fate pursues me/follows my footsteps.” But she pleads with him to stay:

So bleibe hier!

Nicht bringst du Unheil dahin,

wo Unheil im Hause wohnt!

[No, do not leave!

You bring no ill fate to me,

For ill fate has long been here!]Disaster cannot be brought to a house where it already dwells. Her marriage to Hunding is the ghastly state Milton unforgettably described as “two carcasses chained unnaturally together.”

At this point of desperation what awakens in both Siegmund and Sieglinde is the dream of an escape from the torment of loneliness, the almost unbearably intense discovery of their passionate love for one another. That love is, of course, adulterous—the drugged Hunding is snoring in the adjoining room—but the lovers themselves, throughout their ecstatic celebration of the emotional springtide that has suddenly burst upon them, insist upon it as a marriage. They sing of each other as bride and groom. And Die Walküre seems at moments at least to endorse this erasure of the hated bond in terms that Milton himself might have understood. “Unholy [Unheilig]/ call I the vows/that bind unloving hearts,” Wotan sings, in pleading with Fricka to acknowledge the emptiness of Hunding and Sieglinde’s union and the legitimacy of Siegmund and Sieglinde’s love.

Milton, of course, would have regarded Wotan quite literally as one of the demons who does Satan’s will, and he would have been horrified by the lovers’ transgressive violation of all norms of decency and propriety. Their transgression is intensified by their realization that they are twins, brother and sister whom the fates had separated only now to bring them together again in mutual passion. “The bride and sister,” Siegmund sings, “is freed by her brother;/the barriers fall/that held them apart.” For Milton such incestuous unions were the quintessence of evil: Satan impregnates his own daughter Sin, and the monstrous child of their union, Death, in turn rapes and impregnates his mother. That is what it means, in Milton, for the barriers to fall that held people apart.

And yet Milton understood, better than any great artist other than Wagner, the full force of the imperative to escape from loneliness in order to secure the fulfillment of desire and the realization of intimacy. This intimacy in Die Walküre takes on an absolute dimension through the force of narcissism: that is what it means to love one’s twin or, in the case of Wotan, one’s daughter. Already before the love is declared, Hunding is struck by his wife’s eerie resemblance to the stranger who has entered his house: “He looks like my wife there!/A glittering snake/seems to shine in their glances.” And this resemblance is rapturously celebrated by the lovers themselves. “The stream has shown/my reflected face,” Sieglinde marvels, “and now I find it before me;/in you I see it again,/just as it shone from the stream!”

The passage recalls a celebrated moment in Paradise Lost in which Eve, first awakened from her creation, looks at herself, “with unexperienced thought,” in the waters of a clear, smooth lake:

As I bent down to look, just opposite,

A shape within the watery gleam appeared

Bending to look on me, I started back,

It started back, but pleased I soon returned,

Pleased it returned as soon with answering looks

Of sympathy and love.For Milton, Eve must be weaned from this “vain desire”; narcissism must give way to mutuality. But once again the contrast with Wagner is less decisive than it seems: Eve is led, she is told by a mysterious guiding voice, to one who will enable her to realize in the flesh the longings awakened in the glassy reflection: “he/Whose image thou art.”

The Edenic pair have, in Paradise Lost, a deeply passionate marriage. Against a current of theological speculation that located the first experience of sexual intercourse only after the fall, Milton insists (with a striking introduction of his own “I”), on the erotic nature of their bond in Paradise:

…nor turned I ween

Adam from his fair spouse, nor Eve the rites

Mysterious of connubial love refused:

Whatever hypocrites austerely talk

Of purity and place and innocence,

Defaming as impure what God declares

Pure, and command to some, leaves free to all.It is the nature of this bond—its narcissism and its eros—that leads Adam, as Milton depicts him, freely to elect, in full consciousness of what he is doing, to join Eve in the primal transgression:

I with thee have fixed my lot,

Certain to undergo like doom, if death

Consort with thee, death is to me as life;

So forcible within my heart I feel

The bond of nature draw me to my own,

My own in thee, for what thou art is mine;

Our state cannot be severed, we are one,

One flesh; to lose thee were to lose my self.I have stressed the Miltonic moments in Wagner; here, in the lines I have just quoted, is perhaps the most Wagnerian moment in Milton, Wagnerian not in Sturm und Drang but in a sublime spirit of pathos and calm. It was in that spirit that Jonas Kaufmann beautifully sang the words in which Siegmund, told that Sieglinde cannot accompany him to Valhalla, refuses proffered immortality in order to die with her:

So grüsse mir Walhall,

grüsse mir Wotan,

grüsse mir Wälse

und alle Helden,

grüsse auch die holden

Wunschesmädchen:

zu ihnen folg ich dir nicht.[Then greet for me Valhalla,

greet for me Wotan,

greet for me Wälse

and all the heroes;

greet all those fair

and lovely maidens.

To Valhalla I will not go!]It is this choice of a human love and a human fate—against high commands and oaths and obligations—that brings together the great seventeenth-century poet and the great nineteenth-century composer in a shared project. Milton imagined his project as an attempt “to justify the ways of God to man.” But he did something else, something more like a justification of the stained, muddled, and sinful world that humans have created for themselves. “Those deeds of music,” the British philosopher Bernard Williams wrote of the Ring, “cannot in themselves justify the world of compromise and cruelty, but they can express what it would be like for it to be justified, because they invoke a state of mind in which, at least for a while, the world can seem to justify itself.”4 Together Milton and Wagner make it possible for us to hear what it might sound like to find the mortal world enough.

-

1

All citations of Paradise Lost are from the edition in The Poems of John Milton, edited by John Carey and Alastair Fowler (Longman, 1968). ↩

-

2

Citations of the libretto of Die Walküre are mainly from Richard Wagner, The Valkyrie, edited by Nicholas John (Calder, 1983). The English translation is by Andrew Porter. ↩

-

3

All citations of these works are from The Divorce Tracts of John Milton, edited by Sara J. van den Berg and W. Scott Howard (Duquesne University Press, 2010). ↩

-

4

Bernard Williams, “The Elusiveness of Pessimism,” in On Opera (Yale University Press, 2006), p. 69. ↩