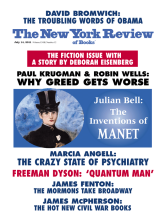

Outside Paris’s Musée d’Orsay, lines are currently shuffling under tall billboards that reproduce, some eight times life-size, L’Amazone by Édouard Manet. An amazone is a horsewoman, and by extension the tight-fitting black riding habit she would wear in the nineteenth century, matched by a black silk top hat. Thomas Couture, Manet’s teacher, noted how this “pretty costume…chastely delineates the forms of the upper body,”1 and Manet’s image dramatizes the tug of interests implied in his words. Equestrianism briefly frees up the woman he’s painting from the “feminine” ruffles and flounces demanded by contemporary fashion, only to squeeze her corseted torso into a stiff black silhouette. Her hair gets pinned back beneath that black silk, all but for a black fringe: between that and the clamp of her collar, her pale cheeks shine out, a sudden sensuous dazzle.

Distended by the giant poster, the androgynous foxiness just about peeps through. And then the publicity also beckons with its blowup of vigorous brushwork, putting forth that pixilated painterliness that’s become one of the culture industry’s standard cues for consumers. Manet, you can make out, went at his subject with a brisk attack, springing from paint swipe to paint swipe—here jostling, there blending—as he moved in on that succulent fresh face.

The momentum of his excitement carried through as he switched brushes to bash a mess of blues and whites around the outline of her head and shoulders. Let that denote the great outdoors—for after all, this “equestrian” was posing on her feet in his studio, rather than on saddleback in the Bois de Boulogne. Her identity is uncertain, but when she came to him in 1882, he was probably already too ill for plein air work: syphilis would within months put an end to his twenty-year career as the most talked-about painter in Paris.

No need to enter the museum to appreciate all this. The reason to join those lines is that the actual small canvas, when at last you encounter it, turns out to be a three-dimensional object. Most specifically and remarkably: the chase and dance of brushstrokes about that face have led up to the moment when the painter dares to slam in some fat central jabs of carmine—the rosebud of the model’s mouth—and scribble on top of them, in a deep crimson upraised ridge, the parting of her lips. This exhibition is entitled “Manet: The Man Who Invented Modernity,” which might lead you to expect a collection of images that somehow defined a new historical era. But Manet the image-maker, reproducible Manet, is not exactly the artist that the Musée d’Orsay’s curators have chosen to represent: or at any rate, not really the artist who comes through. What the exhibition chiefly encourages you to enjoy is Manet’s instincts as a constructor with paint.

Lay on; bring to the fore; maximize. Instructions such as these seem to govern Manet’s hand. By “maximize,” I mean render the subject at its fullest, its most self-suffused. Let those cheeks be very, very bright, that riding habit wholly luscious in its blackness, that sky so very, very blue. Rendering whatever items commanded his attention, inducing them to exist on the canvas, was Manet’s daily working agenda, whatever else may have passed through his mind. A robust, from-the-shoulder line of activity, like kneading bread or whisking cream, this way of his with dense and opaque colors: at the same time nimble, almost skittering, performed with a kind of exultation in its poise. And all the while, driven on by an anticipation of pleasure.

The exhibition brings you close to this joyful working presence because it opens with an education in pictorial values. You are introduced to Manet’s teacher before you get to know the protagonist himself. Thomas Couture represented a progressive, left-liberal position in the Parisian art world when Manet’s father, a senior civil servant, placed the wayward and unbookish Édouard in his atelier in 1850. Three years earlier Couture had made his name in the Salon with a vast historical diatribe against contemporary Parisian mores, Romans of the Decadence: this comes across nowadays (it hangs just across the Musée d’Orsay’s central vault from its exhibition galleries) as an exhaustively deliberate bore. But the stern palette and hard screw-driving efficiency that quicken your resolve to dismiss it were passed on to the studio class in which Manet persisted for six years. A selection of working studies by both master and pupil shows how Manet was taught to draw with brutal concision, seeking out the most compact foundations on which to erect structures of paint. He was to build those structures up, over dun grounds, with lead white and red earth, chilly vine black and drab vandyke brown—plainspoken, workingman’s pigments, nothing that smacked of ideality.

Advertisement

A terrifically forceful 1860 portrait of M. and Mme Manet—the retired permanent secretary, stricken with the disease that would eventually kill his son, grimly clenching his fist—cleaves to these dictates. But the jumpy energy kept close-reined at this stage only swung into action two years later, as Manet turned thirty. The chief catalyst, to judge from the evidence on offer here, was a girl. From Manet’s first head-and-shoulders picture of the eighteen-year-old Victorine Meurent, a model from the working-class districts, a fresh flair entered his paint application, a fresh sureness of focus also. Victorine—the nude model in Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe and Olympia, both painted in 1863 and both borrowed from the Orsay’s permanent collection—projected a uniquely laconic, commanding cool into whatever she sat for. (Anyone supposing that the psychology of those pictures depended principally on Manet should try googling Alfred Stevens’s 1870 portrayal of her as Le Sphinx parisien.) The uproar those two big canvases caused when they were first exhibited derived partly from the novelty of the social alliance—a well-dressed man of means not only cooperating with a nude nobody, but registering her sense of entitlement.

With the advent of Victorine, Manet moved into the technical mode he’s ever since been known for—bouncing creamy brightnesses and radiant blacks off a warm pale ground, dropping the mid-tones, jolting the eye with clashing stimuli. You see it sensationally deployed as he played to Paris’s taste for Spanish subjects, as for instance in the 1864 Dead Torero. Whereas in those two great causes célèbres, the handling of the figure, circumscribing bright flesh with the most concise of contours, seems almost specifically adapted to his model’s outstanding self-possession.

Is this to suggest that with Manet—as, it has often been claimed, with Picasso—the woman leads and the art follows? That he unfolds his imaginative potential through a succession of erotic responses? You could take that romantic reading at least one stage further. In 1868 Manet started painting the most fascinating person he’d ever met. So much is evident from his extraordinary images of Berthe Morisot, five of which appear in the present exhibition. (It so happens that he was by this time stably married to Suzanne, the seemingly imperturbable Dutch piano teacher he had been with ever since he was eighteen. Berthe, as alert to the handsome, charming, and by now famous Édouard as he to her, would end up marrying Eugène, his younger brother.) At this juncture, Manet’s distinctive glaring deadpan modulated as he opened up to the intelligence and mercurial insecurities of a female fellow painter. Morisot broods, glowers, twitches her fan this way and that, and you observe Manet’s brush changing gear and accelerating (see illustration on page 18). Canvas after canvas, all through the 1870s until his untimely death in 1883, was taken at the rattling, hurtling careen you encounter in L’Amazone.

Clearly, this readjustment had a great deal to do with the tendency that Morisot, the younger painter, represented. In principle Impressionism was on a track separate from Manet’s modus operandi. The eyes of Claude Monet and friends were abuzz with a continuous field of color stimuli, whereas Manet was latching onto this object or that object, each quite distinct. In 1874, an individual rapport and a loose art-political alliance (he would never join the Impressionist exhibiting group) drew him eight miles out of town to paint alongside Monet in suburban Argenteuil.

Manet still elected, incorrigible urbanite that he was, to render the grassy banks of the Seine with the greenest of coloring-book greens, the water with the most searing of blues. It was speed of reaction that brought him in line with the younger generation. One of the delights of the exhibition is a four-foot-five-wide canvas whisked together, in half an hour’s work or less, to show Monet painting alongside his wife on his Argenteuil “studio boat” on a hot summer day: Manet was hunched down with them under its canopy, darting about with his black-loaded brush to set the couple in close-up; that must have been some sweaty session.

An exhibition full of heat and light and erotic animus, then. Indeed, Manet’s Blonde with Bare Breasts of 1879 is as dapper an offering of cheesecake as anything in the French tradition, out-Renoiring Renoir; and your appetite is further piqued by a selection of his delicious still lifes. But you can only take this line of reading so far. Manet was famous in his own lifetime and remains so because he was an artist of large ambition. A generation of curating ago, back in 1983—the centenary of the painter’s death—a magisterial exhibition at Paris’s Grand Palais surveyed the range of his achievements. Its shadow still looms over Stéphane Guégan, who has headed the present enterprise. He tells the press he “didn’t want to organise a traditional retrospective; I’m tired of old-fashioned heroic celebrations of this kind.”2 Instead, his team have drawn up a checklist of conceivable personae for the artist, exploring each in turn—often with reference to his Parisian contemporaries—in loosely chronological order. In the light of the vast body of exegesis devoted to Manet, each of their ideas seems full of potential.

Advertisement

From the student of Couture, for instance, they turn to the associate of Baudelaire. Around the turn of the 1860s the aspiring painter spent much time with the ailing poet, some of whose own grimly compulsive pen sketches of fantasy women are on display. One of the real shocks of the exhibition is Manet’s portrait of Jeanne Duval, Baudelaire’s mistress: suddenly, you catch this unmystical scion of secular professional Paris groping his way toward the dark nervy bizarrerie of late Romanticism. The figure of his sitter got blasted away into a flotsam of fragments—one slippered foot, one gross outstretched paw, one tiny lost head—rolling adrift in a great sea of white lace. The violence of the reduction, it would seem, was too much even for Baudelaire to take.

How much did the two men share an agreed common ground? In 1859 the poet drafted his final essay in art criticism, “The Painter of Modern Life,” dreaming of an art that might celebrate artifice and the transience of the metropolis. But Manet’s 1862 Music in the Tuileries, the canvas that seems closest to such a program, has not made it to Paris from London’s National Gallery.

Manet attracted writers—later, he would execute an imperiously public portrait of Zola, and a touchingly private one of Mallarmé—but how much of a reader was he? Possibly he studied The Life of Jesus, the 1863 best seller in which Ernest Renan reshaped the gospel story into a purely human drama: at any rate, in his drive to become the complete painter, Manet decided to take those noble Old Master themes, the passion and death of Christ, and bring them somehow into the present. Bravely—knowing well how these Manets have “revolted his enemies and embarrassed his admirers”—Guégan hopes at last to secure some public appreciation for these “important”3 works. He brings in a gripping head study of Christ crowned with thorns from San Francisco.

But Manet, who disliked repeating his own effects, did not carry its emotionality through into the large-scale Jesus Mocked by the Soldiers (1865) and Dead Christ with Angels (1864). He operated by excitation rather than empathy. It was the prospect of physical objects, whether a model’s arm or face or the chunky folds of his sleeve, that drove his paint constructions onward; and by the mid-1860s, he had put aside not only the tonal modulations of the foregoing French tradition, but many of its other customary props as well. Viewers hoping to interpret the responses collected on his canvases got scant help from the grammars of gesture or facial expression, let alone perspective. Naturally, they started inventing captions for themselves. For the wags of 1865, Jesus Mocked became a ragpicker receiving a foot bath from the nightsoil men, and the Dead Christ “The Poor Miner Raised from the Coal Pit, painted for M. Renan.”4 Guégan now supplies us a line about the latter painting forcing the viewer “to experience [a] triumph over nothingness”5: I’m not sure it fits any better.

Manet, unlike his colleague Degas, was not particularly free with his opinions—his manner was too gentlemanly for that—but he was a man of solidly left-liberal, republican convictions. The exhibition wishes to celebrate this aspect of him also. You are shown a full-scale study for The Execution of Emperor Maximilian—the six-by-eight-and-a-half-foot canvas, reflecting on a disgraceful recent episode in the foreign policy of Napoleon III, that he painted in 1867. With its rush of black scumbles, this study responds to the painterly exuberance of Goya’s 3 May 1808, which was on Manet’s mind after a recent visit to Spain, but eschews its pathos entirely. The riflemen dispatching Napoleon’s hapless colonial stooge come across as cool, charismatic, self-possessed—much on a footing with Georges Clemenceau, the rising star of French radicalism whom Manet would portray twelve years later. Degas, remembering his old friend, said of him that he “had a charming expression. In speaking of a hunchback, for instance, he would say, ‘Ça a son chic.'”6 Style, that’s to say, makes its own set of rules, overriding all varieties of human circumstance. Anyone might look good in their own way, if you come at them aesthetically. It’s a kind of democratizing principle, but it does not exactly equate to fellow feeling, let alone to activism.

In that light, it seems to me that Manet’s politics form something of a visual dead end—and a modest lithograph recalling the tragedies of the 1870 Paris Commune, not to mention a couple of rather contrived marine dramas with radical-leaning back-stories, does little to alter that impression. His sympathies are of strictly historical interest and their resonances no longer sound in our ears. Perhaps the same is true of the bizarre cultural convulsions the painter had to endure during 1863 and 1865, events that for so long have had foundational significance in stories of modern art. Surely Olympia, the object of hysterical abuse when shown at the 1865 Salon, shines out nowadays as a commanding and respectful naked portrait of a strong person, even if spiced up with faintly daft fantasy: as Victorine herself said, his masterpiece.7 The one element in the brouhaha that still remains clear is that this canvas would have dominated the Salon, issuing a blaring challenge to all viewers.

That much reflected the painter’s ambition. Two years later, during Paris’s Exposition Universelle, he opened up a personal pavilion, trying to face down that of Courbet, the apostle of a previous “new generation.” He clearly felt that he possessed what Degas dubbed “a decisive power.”8 He meant to paint everything; he disdained repeats; sooner or later, the great French public would turn his way; sooner or later he would conquer the Salon. He had the means, the wits, the charm: no one who ever met him could find a bad word to say.

And yet, there is not much difficulty in seeing why some of the most thoughtful critics of his own day (Théophile Thoré, for example, by no means an academic reactionary) were tripped up by Manet’s art. Again and again this exhibition returns you to a simple but hard-to-answer question: When does the act of “painting” become “a painting”? You render something, you put some paint down in response to some object. But your act may not be coextensive with the canvas—which was, quite literally, the chief object of the exercise in nineteenth-century art. The act of painting is good and vital, and so, you feel, are the things you depict. You want to paint many things—everything in the world that interests you in fact—provided that each of these acts of painting can be equally vital. But how far can you extend your attention, and when does this work result in a picture?

An individual portrait, a still life, no problem: but beyond that, Manet wasn’t wholly sure. Perspective and suchlike compositional scaffoldings were hardly “painting,” in the engaged and active sense that interested him. But without them, it seemed, viewers got derailed. Sometimes their doubts infected him and he ended up cutting out morceaux from unpersuasive multifigure scenes—the best bits, the fragments that in isolation still felt alive. Perhaps the soundest solution was the recycled composition. An arrangement of poses derived from Raphael or Titian or the Spanish painters would, he hoped, offer him plenty of room to construct with paint in the way that mattered, while at the same time delivering what the Parisian public would recognize as a picture.

Spain looked the best hook on which to hang his coat; Paris had been in love with Spanish painting ever since he was a child, and toreros and gitanos were surely marketable. (When at last he visited the country in his thirties, his pampered French stomach couldn’t handle the olive oil, and for three weeks he starved for the sake of the Prado.) And then within that fantasy zone of blackness, austerity, and passion, there was to be found the best oil painter of all time. A very personal hero: for Velázquez had closed in, two centuries before, on much the same riddle that troubled Manet himself. What is it to set down an appearance within a canvas?

With incomparable grace and intensity, the great court painter isolated the act of representation, dangling it quizzically, as if in a void. Manet’s direct and startlingly powerful imitation of Velázquez’s Pablo de Valladolid in his 1866 Le Fifre—a boy playing a fife in the Imperial Guard—is a hand held out to Velázquez across history, proposing that there’s an eternal conundrum at stake.

Nonetheless, Velázquez is truly incomparable. It hardly disparages Manet to observe that he couldn’t focus on his subject matter with such concentration, so consistently, as the painter of Las Meninas. Or perhaps this is the point at which I want to raise a doubt. I think of the Déjeuner sur l’herbe and its busked, any-old-how stage-set foliage: I think of the way some gouts of white paint sit high up on that canvas, and of the way a bathing robe might sit on a woman’s body, and of how the one and the other never quite tally; and I think of remarks made about some other Manet painting (and there are so many it might have been) by that great English painter and critic Walter Sickert: “A lack of any very definite conviction:…an execution that seeks for distinction in a kind of non-committal négligé, and, to that extent, achieves it.”9

Flip over that barbed equivocal phrasing, and you arrive at Bob Dylan singing “There’s no success like failure, and…failure’s no success at all”—a line that covers a great deal in art during the years between the Déjeuner and Dylan’s “Love Minus Zero/No Limit,” and indeed in the years that have followed. In that sense, yes, Manet is “the man who invented modernity.” (Or “modernism,” as many historians would have it.) It is not simply the quality of his attention that pointed the way for generations to come: the way of rendering things that I see as maximal, full-on, and that others—a dismissive Courbet, or Clement Greenberg, devising an ancestry for abstraction—have preferred to call “flat.” It is the quality of his inattention. It is what happens when he falls between stimuli. Keeping one eye, for instance, on Degas, who has taken him out to the races at Longchamp, and another on a photo in his studio of running horses, and trying to conceal his unfamiliarity with this material by means of a busy listless bluster. Or when he bashes about with his brush—this time with a Goya print to hand—in an effort to contrive the excitement of some distant bullfight, in some arena he’s never entered; or mumbles a fashionable mock-Japanese, in his Portrait of Nina de Callias (1873–1874). More generally, it is the sense that at the back of his working mind, neither squarely acknowledged nor yet dismissed, lurks a memo that reads: there ought to be a story here, but I’m not yet sure what it is. In all of this, I see the aestheticized halfheartedness of which Sickert speaks.

There is a strong argument within modern art that halfheartedness ought to be aestheticized: it runs all the way down through Duchamp and Jasper Johns to Kippenberger and Basquiat; in fact you find it in Sickert—the painter of Ennui (1913)—himself. Complementing that, there is an enormous corpus of interpretation that insists: do not adjust your heart, there is a fault in reality. The “modern” is the deracinating historical condition that makes it impossible either to tell a proper story or to abandon the impulse to do so. Nonetheless, if an artist aims to mature, he might find it expedient to dispense with that dismal wisdom.

The Paris show includes two light-filled and witty canvases from Manet’s final years that suggest as much. In Chez le père Lathuille (1879), he decided quite firmly what story he wanted to tell: the two characters, a pushy young cad and the prim heiress he’s trying to seduce, are gazing at one another with rapt attention, in a way that’s new to his oeuvre; moreover, he has retuned his graphic language in order to deliver it, using sunlight to describe forms as never before. Whereas a fabulous small view of the Rue Mosnier, the street beneath Manet’s studio window, slyly relates a story about urban disconnection itself—about the way a one-legged veteran of the Commune hobbles along under tricolors put out for a public celebration, about the juxtapositions of builders’ rubble and billboards, about the big empty sidewalks next to a solitary parked fiacre. Here, more than anywhere else in this show, we get an image setting out to describe nineteenth-century “modernity” and its strange new spaces—an agenda already explored by Degas and by his Berlin friend Adolph Menzel.

It would be fascinating to look at the Rue Mosnier canvas in relation to Music in the Tuileries, painted sixteen years before, not to mention The Railway (or Gare St Lazare, 1873), which remains in Washington’s National Gallery. Most of all, in relation to A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882), Manet’s final major canvas, now in London—for lack of which, visitors to the Musée d’Orsay galleries get put on a lopsided tour with nothing substantial arriving at the end to counterbalance the great, weighty Salon submissions made near the start of his career. For all the large promise of its title, “Manet: The Man Who Invented Modernity” is a diffident, even whimsical venture, with its multiplicity of tentative themes and its bemusing guest appearances. (Why, for instance, include a large and vapid Henri Gervex?)

The catalog offers numerous remarks by Guégan, by turns scholarly and rhetorical; brief but stimulating essays by Laurence des Cars and Nancy Locke; a jolly, rambling interview with that veteran of the Left Bank Philippe Sollers; an ill-thought-out illustration layout; and frustratingly little information on individual exhibits. If you are looking for a single volume about Manet, the catalog of the 1983 exhibition—the mighty ancestral enterprise to which the present show so clearly defers—remains infinitely better value. On the other hand, a few hours in the company of some 140 sparky, provocative, three-dimensional Manets are worth a very long journey indeed.

-

1

“Voyez le joli costume d’amazone, comme il dessine chastement les formes du haut du corps“: see Thomas Couture, Méthode et entretiens d’atelier (1868), p. 258. I was pointed toward this reference by Anne Coffin Hanson, Manet and the Modern Tradition (Yale University Press, 1977), p. 86. ↩

-

2

Guégan interviewed in “Manet Reimagined,” The Art Newspaper, April 2011. ↩

-

3

An epithet he uses later in the Art Newspaper interview, in a sentence this paraphrases. ↩

-

4

“Le Pauvre mineur qu’on retire du charbon de terre, exécuté pour M. Renan“: phrase from La Vie Parisienne of May 1, 1865, quoted in Manet, 1832–1883 (Metropolitan Museum of Art/Abrams, 1983), p. 199. ↩

-

5

Manet: The Man Who Invented Modernity, p. 160. ↩

-

6

More exactly, this is Sickert remembering Degas remembering Manet, in Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, edited by Anna Gruetzner Robbins (Oxford University Press, 2000), p. 417. ↩

-

7

“I sat for a great many of his pictures, in particular Olympia, his masterpiece.” Victorine Meurent quoted in Henri Perruchot, Manet, translated by Humphrey Hare (World Publishing, 1962), p. 261. ↩

-

8

“There is in Manet a decisive power, a sort of strategic instinct for pictorial action.” Degas quoted in Paul Valéry, Degas Dance Dessin, in turn quoted in Michael Fried, Manet’s Modernism (University of Chicago Press, 1996), p. 581. ↩

-

9

Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, p. 465. ↩