In an essay about the Sahara, “Baptism of Solitude,” Paul Bowles tells us many interesting things about oasis towns (where the fertility of cultivated plants is all-important and birds are hated as seed-stealers) and about the Touareg, a desert-dwelling tribe whose name in Arabic means “lost souls” but who call themselves the “free ones.” But what Bowles (who was born a hundred years ago this past December) prizes above all else about the desert is its absolute solitude. “Why go?” he asks.

The answer is that when a man has been there and undergone the baptism of solitude he can’t help himself. Once he has been under the spell of the vast, luminous, silent country, no other place is quite strong enough for him, no other surroundings can provide the supremely satisfying sensation of existing in the midst of something that is absolute. He will go back, whatever the cost in comfort or money, for the absolute has no price.

As his novel The Sheltering Sky (1949) suggests, the absolute solitude of the desert may exert a strong appeal, but that magnetism is not necessarily salutary. In it two young Americans, Kit and her husband Port, head farther and farther into the desert, even though he is seriously ill and will soon die. When they finally arrive at a remote outpost, Kit observes that at last there is no “visible sign of European influence, so that the scene had a purity which had been lacking in the other towns, an unexpected quality of being complete which dissipated the feeling of chaos.” Here Port dies and Kit enters her own slow process of abjection and self-destruction. “Purity” is the quality Bowles’s characters cherish, but it is a purity that destroys them.

Bowles embraced the desert as a Christian saint embraces his martyrdom. His self-abnegation and his love of traditional culture made him one of the keenest observers of other civilizations America has ever had. Unlike some of his countrymen he did not brashly set out to improve the rest of the world. For Bowles, Americanization was the problem, not the solution.

Although The Sheltering Sky was a first novel, it reads like the work of an experienced master. Bowles was in his late thirties when he wrote it; he had long been living in a sophisticated milieu; and he had carefully edited the remarkable novel Two Serious Ladies by his wife, Jane Bowles. The Sheltering Sky has none of the awkwardness or unevenness of a maiden effort.

It is also surprisingly adroit technically. Novels need different openings than stories do; a novel needs an opening that is inviting, engaging, but not too definitive or even too satisfying. The Sheltering Sky opens with a narrative that wavers between the point of view of Port and Kip without giving away too much about either character. And in just a few pages it establishes the seedy, menacing atmosphere of a North African port.

Right away we’re given a tableau on the terrace of the Café d’Eckmühl-Noiseux (the German-French name in an Arab country suggests the cultural confusion of colonialism) where three Americans—two men and a “girl” (as Bowles calls her)—are observed from a distance. One of the men is looking at a map. Then we suddenly are privy to the fact that maps bore Kit whereas they fascinate Port. They’ve been married twelve years and are constantly in motion. When they’re not traveling, maps continue to attract him. Now they’re in North Africa with a great deal of luggage.

We switch from access to Kit’s thoughts to an external observation of her: “Once one had seen her eyes, the rest of the face grew vague, and when one tried to recall her image afterwards, only the piercing, questioning violence of the wide eyes remained.” A strict follower of Henry James would object to all these shifts of point of view, but in fact they give a strong inside-outside sense of Kit and Port. It’s important that we know that Kit is slightly mad—and this objective snapshot of her eyes and their “violence” gives us our first clue.

Kit says that she fears everything throughout the world is getting homogenized, and Port is quick to agree that indeed everything is becoming grayer and grayer. “But some places’ll withstand the malady longer than you think. You’ll see, in the Sahara here…” At this point we’re only on page 8 but already the Sahara has been introduced. It will be one of the main characters in the novel. And its introduction is ironic; it will turn out that the desert will be monochromatic, literally, and that the oasis towns will be dirty, dusty, almost featureless, and full of diseases.

Advertisement

Afterward Port wanders through the town on his own. Prefiguring the central movement of the book (the steady push inland), in this opening scene he keeps walking farther and farther—away from the sea, toward the desert—into dangerous zones of the town. This contact with “a forbidden element” elates him. “The impulse to retrace his steps delayed itself from moment to moment.” Someone throws a small stone at him and hits him in the back. But still he plunges on into the terra incognita of the town: “He sniffed at the fragments of mystery” in the wind boiling up out of the desert, “and again he felt an unaccustomed exaltation.”

Port meets a man who appoints himself his guide; he arranges for Port to have sex with a very young girl in a tent in a foul-smelling dump at the bottom of a steep hill. Port catches her trying to rob him of his wallet and he flees into the darkness; he then becomes completely lost and only with great difficulty finds his way home to the hotel. Being endangered and lost foreshadows Port’s fever-dream “travels” at the end of the book when he is dying and fears he won’t be able to find his way back to the room where his physical body is lying and suffering.

The young prostitute tells him a tale that becomes emblematic and gives its name to this section, “Tea in the Sahara.” In her story three prostitutes suffer the attentions of their ugly customers because once they met a handsome, tall nomad and they long to follow him someday to the Sahara where he lives, but they never earn enough. Finally they decide to pool their resources, take a bus south, and then join a caravan. Once they are in the Sahara they sneak away from the caravan and keep climbing one dune after another, always looking for the highest one. They’ve brought along their teapot and cups and plan to drink tea in the desert. But they’re so exhausted they fall asleep, die, and are found days later with their tea glasses full of sand.

Two hundred pages later, after Port’s death, Kit joins a handsome nomad and, like the man in the tale, he is mounted on a mehari, a tall, slender, fawn-colored camel with a small hump. There are other parallels to the fable: the awful British tourists, the Lyles, drink tea no matter where they go; tea-drinking is their proof that they are better than the savages they live among. They carry with them the tea and tins of English biscuits. Finally, the annihilation that the three girls undergo in the Sahara is really what Kit and Port are both courting.

Both Kit and Port are passive and fatalistic, but in a curious way they are extremely active in pursuing their self-destruction. Just as Port is about to get his stolen and all-important passport back (and thus recover his Western identity), he flees with his wife to an even more remote town. He should be heading back north to the coast and an airplane that will convey him to the hospitals of Europe or America; he is very ill and a return to the first world is his only hope of recovery. But he flees the promise of recovery. After his death Kit flees—not once but twice. In fact the book ends with her melting into the crowd and escaping her well-meaning if slightly dim escort from the American consulate; at least we presume she’s boarded the tram that is inching through the crowds and heading out to the very edge of the city. She is inarticulate with madness and even smells bad.

On the level of conventional novelistic plot and motivation, one could argue that Port is fiercely if silently jealous of Tunner, the American who is traveling with them, and that Port flees him because he is afraid of him as a rival, just as one could argue that Kit feels so guilty about not being with Port at the moment of his death that she cannot bear to contemplate what she has done. As she looks at his dead body, Bowles writes,

These were the first moments of a new existence, a strange one in which she already glimpsed the element of timelessness that would surround her…. Now she did not remember their many conversations built around the idea of death, perhaps because no idea about death has anything in common with the presence of death.

She goes staggering out into the desert and hands herself over to a passing caravan. The merchant and his business partner fight over which one will have access to her sexual favors. She only too willingly surrenders to her captors, who keep her drugged, turn her into a sex object, and whose language she cannot understand. Bowles does not, however, resort to the language of psychology; his vocabulary is metaphysical (“the element of timelessness” and “the presence of death”). Most novelists are careful to “motivate” their characters with plausible explanations of their behavior; Bowles submits Kit and Port to eternal philosophical principles, much like the characters in Greek drama.

Advertisement

But there are some faint traces of motivation or at least consistency. Kit has been portrayed throughout the text as a woman who has irrational fears and superstitions, who sees omens and portents everywhere, and is, in a word, slightly crazy. Port, who is presented as being in love with his wife and longing for a rebirth of their sexual intimacy, never does anything to achieve this goal. On the contrary, he is the one who invites Tunner, his rival, to join them. And he never speaks openly of his love to Kit.

This deep passivity, we could even say this obstinate passivity, was an earmark of Bowles’s personality and oeuvre and is so far from the average person’s experience and behavior that it remains a permanent puzzle for most readers. One of Bowles’s friends said to me once, “Paul was as passive as some of his characters.” For instance, he refused to encourage or discourage a woman who was courting him after Jane’s death. In You Are Not I, her portrait of Bowles, Millicent Dillon quotes Bowles as saying, “I never said anything. Well, I never do. I don’t know why you have to say something. You just have to go on living. People can guess for themselves whether it’s yes or no.” Elsewhere, when Dillon asks him if his feelings were hurt when one of his Moroccan lovers left him for a rich woman, Bowles says in his best Zen manner, “I don’t know. I don’t know what it feels like to have your feelings hurt.” In his most troubling short story, “Pages from Cold Point,” the father who has just slept with his son says, “Destiny, when one perceives it clearly from very near, has no qualities at all.” In the story “You Are Not I,” the narrator says, “I often feel that something is about to happen, and when I do, I stay perfectly still and let it go ahead. There’s no use wondering about it or trying to stop it.”

Halfway through The Sheltering Sky Port says:

Everything happens only a certain number of times, and a very small number, really. How many more times will you remember a certain afternoon of your childhood, some afternoon that’s so deeply a part of your being that you can’t even conceive of your life without it? Perhaps four or five times more. Perhaps not even that. How many more times will you watch the full moon rise? Perhaps twenty. And yet it all seems limitless.

I mention this passage—which is a striking and original thought in any event—partly because it is the way I feel toward The Sheltering Sky itself. I read it once in my twenties and I remember being impressed by the seamless beauty of the writing, the way the constant pressure of the narrative drives forward into disaster after disaster, much as the characters at every point make the wrong choice, precisely the one that will doom them. I also admired the largely hidden, offstage working of the narrative strategies; so much is left out. We don’t know where Kit’s and Port’s money comes from, how they met and married, why they feel so attached to one another despite the sexual stalemate they’ve arrived at, what the attraction of the desert and Arab culture is for Port (Kit would be just as happy if not happier in Italy or Spain), how he survived the war without serving in it. They both seem not merely rich but old-rich in American terms—they have lovely manners, they speak fluent French, they have beautiful clothes, they are in no way jingoistic. But how did they get to be this way? Bowles explains nothing; the constant forward impetus leaves us so breathless with anticipation that we never stop to ask all these unanswered questions. There is no willful obscurity in the way the tale is told; it’s just that there are big omissions that we forget to worry about.

I suppose because most readers knew that both Paul and Jane Bowles were homosexual (or was it bisexual?), The Sheltering Sky was sometimes read, especially in the beginning, as a story that arose out of the sublimation or the concealment of the author’s homosexuality. Port’s dalliances with the dangerous young girl in the first port town and with a blind girl whom he never succeeds in seducing despite his frantic efforts—these misfired but obsessive meetings feel much more like the kinky homosexual behavior of the period than normal heterosexual adventuring. The 1940s were the time of the “danger queen” in search of sex with “straight trade” who might turn “dirt” (that is, become dangerous) at any moment; Tennessee Williams recounts dangerous encounters with “dirt” in his Notebooks from the same period, as do other gay memoirists of those days.

And then Port’s ambivalence about the conventionally handsome Tunner seems to dramatize his mixed feelings about his marriage. On the one hand he appears to be encouraging Kit to cheat on him with Tunner—but at the same time he is sarcastic, even openly hostile, about Kit and Tunner’s nightlong train ride together (the one moment when they do in fact betray him). Although Port says he intends to revive his physical affair and his love for Kit, he is too deeply passive and even perverse ever to act. He prefers to wait—not for anything she might do or any sign she might give, for he feels confident that she is receptive to his love at every moment and does not need to be propitiated—no, he is waiting for the shifting of his own inner machinery.

My memory is so bad that I didn’t recall much about The Sheltering Sky when I came to write my novel The Married Man. It is in some ways an autobiographical novel, never more so than in the closing section that takes place in Morocco. I had a French lover, Hubert Sorin, with whom I lived mostly in Paris for the last five years of his life. After less than a year together we learned that he was HIV-positive and already far advanced in the illness.

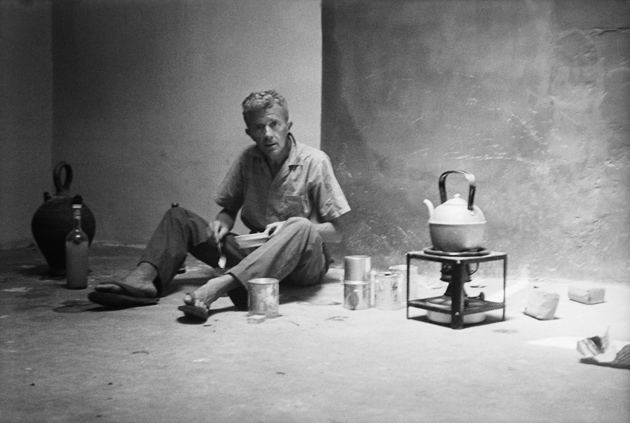

A few months before he died he said he hated the cold and damp of Paris and begged me to accompany him to Morocco. We spent some time in Marrakech; Hubert wanted to come back a month later and to please him I tried to rent a beautiful riyadh in the heart of the old city. The lease was about to be signed, but then the owners got a glimpse of Hubert. They must have been shocked by his appearance; he was blade-thin, tottering, obviously dying. The deal fell through and to console him I said we’d fly the next month to Agadir, rent a car, and drive inland to the small beautiful town of Taroudant. We did so despite the warnings of all our friends in Paris, who said he wasn’t well enough to travel. He was already suffering from pancreatitis and unable to keep food down. But Hubert insisted—he wanted to get to the Sahara. And I was almost hysterically in denial. We spent a few days in a hotel, formerly a wonderful old pasha’s palace in Taroudant built right into the town walls—and then started heading west and south, toward the desert.

Foolishly I imagined that traveling in a car couldn’t be all that tiring. But Hubert had no flesh left on his body and even sitting was very painful for him. To hide his thinness he started wearing long white Moroccan robes. One of the medications he was taking made him turn much darker in the sunlight. Soon, because of his darkness, his Mediterranean features, his starved-looking body, and his robes, people began to assume he was Moroccan.

Of course we should have turned back and returned to France, but Hubert insisted we go farther and farther. We reached Ouarzazate, then headed south for Zagora. Then we drove across the desert on a dirt road to Erfoud. There he could no longer walk and he’d become incontinent. It was a miracle that the hotel manager gave us a room.

I realized in Erfoud that we must try to get a flight back to Paris—but first we had to return to Ouarzazate or possibly Marrakech. As I wrote in The Married Man:

When they arrived in Ouarzarzate at last, Julien said he couldn’t walk into the hotel.

“You can and you will!” Austin shouted angrily. “We just need to get to the room, and you’ll feel better….”

“No,” he whispered. “I can’t. Don’t you see it’s over?”

“It’s not over. We’re going to get that plane back to Paris—“

“I hate you!” Julien hissed. “Je te déteste!” was what he said in French, the exact words. “Don’t you see? I’m covered in shit.”

“I’ll clean you up.” Austin lifted him up, stood him beside the car, threw his dirty robes on the ground and helped him step into trousers.

“Now we’re just going to walk normally past the desk and to the room.”

“I can’t,” Julien wailed. “Can’t you see? It’s over. Why won’t you let me go?”

Austin, grim and determined and cold with fury, put his arm around Julien’s waist and walked him toward the entrance to the hotel, but suddenly Julien fainted and crumpled onto the grass. A Frenchman who was walking by said, “What happened? Call an ambulance, for God’s sake. I’ll call an ambulance,” and he ran into the hotel and insisted the clerk phone the hospital.

Austin looked down at this tiny, shit-stained effigy in the grass and he sobbed. “I can’t, I don’t—“ but he didn’t know what he was saying and his whole body was seized with a violent fit of trembling which was only more sobs and at last tears. It was as if his will, so long screwed up to its tightest, tautest pitch, had at last snapped and now was hanging down as useless as a violin string. After so much tuning and sawing and plucking, after so much rapture and suffering had been wrung out of it, at last it had snapped and no one was more surprised than the instrumentalist himself.

I suppose if someone had asked if I’d been influenced by The Sheltering Sky in writing this book I might have nodded vaguely. But I would have protested that everything I described had actually happened to us. We were not a neurotic couple tempting fate—and yet we were. Hubert’s illness wasn’t psychogenic, but Port’s illness wasn’t either. Our persistence in fleeing help was similar. Even one particular detail was similar. After Port dies, Kit walks through the oasis town as drums beat. “The season of feasts had begun,” Bowles writes; exactly as the beginning of the very end for my character occurs during the festive end of Ramadan.

We eventually hired an ambulance to take us through the freezing Atlas Mountains to Marrakech and a crummy Arab clinic, the Clinique du Sud. I should have insisted we go to the good European clinic at the Mamounia Hotel but I didn’t know about it. Hubert died while I was asleep in the bed beside his in his hospital room. His last words to me had been those he’d said a day before—“I hate you.” Just as Kit was not present when Port died, I was asleep when Hubert passed away. I awakened to see that his drip had stopped and then, when I looked closer, I saw that his face was startled, exactly as if he’d seen something horrifying.

The second time I read The Sheltering Sky, three years ago, I was mainly struck by the deliberate perversity of the characters. I didn’t notice that Bowles provides at least a few motivations for their behavior. But I’m sure I wasn’t letting myself absorb very much of the text—it was too close to home.

Then at the beginning of 2011 I read the book for probably the last time. It took me the whole month of January to get through it—so painful was it. I became quite depressed reading it. Port’s coldness reminded me of my own. Kit’s madness was also like the breakdown I’d had when Hubert started to slip away from me. The feeling of living through a death in an utterly alien world was all too familiar.

I was also struck by how different our books are, not to mention that Bowles’s book is a work of genius. There is lots of humor in my novel and none in The Sheltering Sky. Bowles gives a dry gray picture of postwar Morocco whereas my book is a lot more colorful—a critic might say it’s the picture-postcard approach. Bowles writes in a cool metaphysical dialect whereas mine is all human, circumstantial, psychological. All of which is a way of saying how extreme and unusual Bowles’s book is, which is also what is remarkable about it.

Was I influenced by Bowles’s book? Yes, in the sense that it gave me permission to narrate my personal drama against the unfolding of the Moroccan landscape. In the sense that I counted on that landscape to do my feeling for me, just as Bowles had done. In the sense that the interaction between first-world characters and third-world “extras” was crucial to both books. But it would be mere superstition to suggest that my life was inspired by a half-forgotten reading of The Sheltering Sky. For one thing I wasn’t that much in control of my life at the time. Hubert, who never read the book, was the one endlessly pressing us toward the desert. He was the one who wouldn’t turn back.

Oddly enough, he was not the first person dying of AIDS whom I’d accompanied toward the Sahara. What is it about the desert that attracts the ill and the dying? Could Bowles be right that it represents a taste for the absolute? And what does that mean?