North by Northwest is a movie we think we remember. The set pieces are common currency fifty years later: meeting that willing blonde on the train; the auction scene; the crop-dusting plane on the prairie; and the finale on the perilous faces of the Mount Rushmore monument. And everyone says, “Of course, Cary Grant!” He’s an emblem now, not just of the sophistication he seemed to embody, but of an age of effortless entertainment.

Grant and his director, Alfred Hitchcock, understood this gloss even in 1959. So they pushed a brief marvel into their picture. Roger O. Thornhill (it says R.O.T. on his monogram match books) is on the run. He is confined in a hospital room for his own safety. He needs to get out, so he slips through the window at night and into the next room, in darkness. An “attractive brunette” sits up in bed and puts on the light. Roger is on his way out. “Stop!” the outraged woman shouts. But once she gets a proper look at him she says, “Stop” (“in an entirely different tone of voice”—this is from Ernest Lehmann’s witty script). It’s a throwaway, but we know what she means. We want more of his shy glory.

Nor is it enough to pass over North by Northwest as just the comic relief Hitchcock allowed us and himself between Vertigo and Psycho. North by Northwest is a screwball thriller, but it’s also a chance to see Grant as a charming, frivolous advertising man with wives strewn in his past, who is pulled up short by feeling and relationship. Eva Marie Saint’s character seduces him on that train because it’s her job (she’s a secret agent), but Roger goes from being her mindless, unquestioning pickup to falling for her. So this debonair suave man looking like Cary Grant must grow up and face emotional consequences. Still, the film was so wild that in 1959, the world said, “Oh, it’s just Cary Grant. He’s being himself!” The acting Oscar that year went to Charlton Heston grappling with Ben-Hur—Grant wasn’t nominated.

The world has been catching up. In 1975, I said that Grant was “the best and most important actor in the history of movies,” and the same year Pauline Kael wrote “The Man from Dream City,” a fine appreciative essay for The New Yorker. In 1975 my enthusiasm was sometimes dismissed as English, youthful, and foolish, and the point may have been harder to digest in that I wasn’t proposing to admit Grant to the pantheon that included Charles Laughton in Mutiny on the Bounty, Paul Muni and Emil Jannings doing anything, Laurence Olivier as Richard III, or Marlon Brando in On the Waterfront. These strenuous pieces of masquerade were all very well, but I was trying to propose a different approach: that the best movie acting was more natural than naturalistic; it involved a slightly uneasy, half-mocking, reticent presentation of self. It could be seen in Gary Cooper, John Wayne, and above all in Cary Grant. A Richard III by Grant would have been fit for The Carol Burnett Show (and no harm)—yet his Hamlet might have been intriguing.

What Grant had been doing over the years was to be “himself” and let the scrutiny and fantasizing of the audience take him over, while remaining mysterious. So in North by Northwest he was a facetious hero who sobers up. In Notorious he was a mean spirit who learns generosity. In Bringing Up Baby he was a learned chump who finds the need for fun. In Holiday he is a poor fellow who sees through wealth and class. In The Philadelphia Story he teaches a beloved prig to behave naturally. In The Awful Truth and Suspicion we ask whether we can trust him. What it amounts to is taking the audience expectation—“Oh, it’s Cary Grant again”—and letting us see a degree or two more deeply, without sacrificing fun, romance, adventure, and being at a popular movie. Cary Grant was important in revealing the artful and perilous fantasy exercised in most motion pictures. The fun was slippery and insecure—no wonder Grant was a wreck.

Not that those lessons worked on everyone.

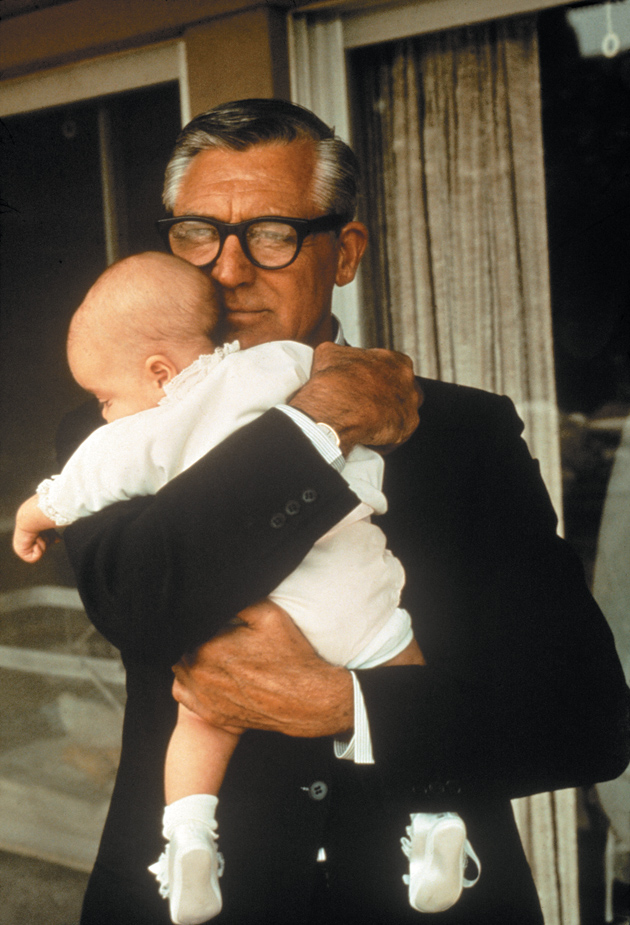

Jennifer Grant is the daughter of Cary Grant and Dyan Cannon, born in 1966, when her father was sixty-two and had retired from screen- acting. She loved her Dad, which is as understandable as her missing him, though he died in November 1986, when she was twenty. But this reminiscence—the first writing by anyone who was family to the great actor—is disappointingly dull on many of the things that make Grant fascinating still. Maybe the most intriguing impression within the book (and I’m not sure it’s one the author gets) is how busy Cary Grant was being an endlessly kind, affable, attentive, and providing “Dad” to fend off other matters of concern.

Advertisement

Grant had had three previous marriages—to Virginia Cherrill (the blind girl in Chaplin’s City Lights), to Barbara Hutton (the Woolworth heiress), and to the actress Betsy Drake (they were married from 1949 to 1962, his longest partnership—she would go on to become a psychotherapist and Grant credited her with helping him find some peace in their years together). He lived with Dyan Cannon, another actress, thirty-three years his junior, for a few years before their marriage, but they were divorced when Jennifer was two. Then in 1981 he married another much younger Englishwoman in public relations, Barbara Harris.

The portrait of Grant in this book is of a decent, gentle man who longed to be liked, and to like others, who seized upon being a father at last and played the part—as he had played so many others—to perfection. Which is not to say that he was pretending, or being insincere. Acting was his freedom and escape. But he might have been at a loss himself, too. As the inner man sometimes admitted, “Cary Grant” was a role he longed to fill, no matter the wistful distance from which he observed that paragon.

It’s hard not to be tough on Jennifer’s monotonous album of happy days and “good stuff.” Amid the happy days there may be great problems, like being too wrapped up in the legend of this Dad who knew everyone, could take her to Palm Springs, Las Vegas, and Monaco, put her in a front row seat so that Frank Sinatra sang to her, made sure she paid her quarterly income tax estimates at the age of twelve, but liked to curl up with her in front of the TV, and kept every note and drawing she ever did. “Okay, I had a crush on Dad,” she admits. “Okay, more than a little crush on Dad.”

Jennifer Grant doesn’t mention it, but Grant and Dyan Cannon had a fierce custody fight over her when they divorced. Good Stuff never harps on divorce or acrimony; it doesn’t do pain or difficulty. It doesn’t actually say much about the mother (though the book is dedicated to her—and Mom has her own book coming in the fall), but it lets us believe the daughter was more with Dad, just doing ordinary things, like riding horses in the desert, cruising the Alaska shore, having box seats for Los Angeles Dodgers baseball games, and staying home, because he didn’t like to go out too much, with an understandable horror of being gaped at.

Of course, they went to Monaco:

Dad loved Monaco. What’s not to love? Owing to his close friendship with Prince Rainier and Princess Grace, we stayed at the palace. We dined in the private quarters, with Rainier, Grace, and some combination of Caroline, Albert, and Stephanie, depending on who had what plan which night. We ate loup de mer, cocktailed on the terrace overlooking the Med, rode in limousines over the cobblestone streets, and somewhat let our guards down together.

Somewhat? Did Grace ever admit what a bore life could be in “what’s not to love” Monaco?

Or consider this account of Dad and Frank Sinatra together:

Dad and Frank were gifted with the indefinable incandescence of charm. They were high on life and they radiated. Their containers were well honed, structured, and self-defined. They surrounded themselves with stringent supporters. Their give-and-take required a high level of circuitry and tolerated few leaks. So where others might gush that high feeling, they let it out in a constant stream. They flirted with almost everyone and everything and life graciously flirted right back.

I’ve read that over several times and I’m still not sure what it is trying to say. It starts off in a mood of adoration, but what are the “circuitry” and the “high feeling,” and what’s this innuendo about “stringent supporters”? I had a couple of conversations with Cary Grant, and while he ached to be pleasant and liked, another keynote was his insecurity—the worry that he had misunderstood something or was being misunderstood, that everything wasn’t quite clear and agreeable, that the camera’s “take” that day hadn’t been smooth and okay. It leaves one feeling how difficult some of those big occasions may have been for a girl who needed to grow up and fight her Dad sometimes.

It’s at home that their emotional affinity flourished. Some of this is very touching. Still, there are things that come across as stranger than Ms. Grant seems to guess. Her father apparently did keep every bit of paper she touched. He also made sound recordings of their life together, and left her the tapes—not only serious conversations, or parties and festivals, but just empty time passing:

Advertisement

How many times have I sat listening to a virtually blank hour-long tape? Voices in the background. Shuffling feet. A door slamming somewhere. “Hello’s” voiced from someone or other we knew in those years. And then in the midst, Dad appears and says he’s going to go sit by the pool and have his sandwich…. Did Dad review the tapes before saving them? He was so damn organized, he must have. Perhaps Dad was a fan of the extended Pinter pause?… Normal days. Nothing much goes on. We sit around, play some games, have a bit of chat…. This is it. Not every day is a graduation. The middle stuff of life. Value the middle stuff.

Is it always “stuff”—the stuff of love, the middle stuff, the good stuff—or might there have been some worry powerful enough to have turned Cary Grant into the most intelligent, complicated, relaxed screen actor there ever was? And what is the price of seeming relaxed? I’m not sure Grant the actor could have articulated his own way of doing things, and I can understand that he might not want to analyze it with his daughter. Still, it is striking that she has so few questions about him.

In Grant’s last years, Jennifer Grant was a history major at Stanford. After his death, she gave that up to be an actress herself. So we marvel at her failure to talk to Grant about his work:

One would think I had a treasure trove of stories from his movie career. Not so. For whatever reason, we never discussed his life as an actor. He never told me of the many great directors, writers, and actors with whom he collaborated. How tremendously silly of me not to ask. Dad had been in it, but he was certainly not of it.

There’s the legend of how completely he had moved on from acting to be a father. But it’s not accurate. In those last years, Grant developed and presented a one-man stage show—A Conversation with Cary Grant—with film clips first and then the actor just talking to the audience, telling stories and riffing on moments from his films. It was high entertainment, and he was thinking of putting it on film for television, fussing over the details and technicalities of the staging.

Jennifer Grant mentions the show briefly, and leaves it unclear if she saw it, yet it meant a lot to the father. He did it thirty-six times, often with the help of Barbara Harris, and he died in Davenport, Iowa, while preparing to put it on. Jennifer also reveals her difficulty watching him on film:

How does it feel to see my father on-screen? It’s mostly squeamishly uncomfortable. Admittedly, I beam with pride and laugh out loud. However, there he was for all those years…doing all these amazing things, and I wasn’t there with him. Grace Kelly gets to swim in the sea with him. I’m a good swimmer. That should be me. Katharine Hepburn flusters him. I could do that. Tony Curtis is an impertinent rascal. That’s my job! If I yell loud enough, will he pop out of the screen for me? My Daddy, my Daddy, mine mine mine!!!!

But this is the daughter who didn’t ask about his acting and who turns not just coy but a little aggressive when obliged to consider the rumors about Grant’s sexuality. At the start of her book, she tells us:

He said that after his death, people would talk. They would say “things” about him and he wouldn’t be there to defend himself. He beseechingly requested that I stick to what I knew to be true, because I truly knew him.

Ms. Grant admits that she has read none of the several books about Grant (for example, Graham McCann’s biography, Cary Grant: A Class Apart, published in 1996, or Marc Eliot’s from 2004). She says, “I would rather know, as I do, his essence.” But this very contemporary lack of historical curiosity and concentration on the “essence” would be crippling for any memoir, not least of a great performer. Jennifer Grant’s acting career has not prospered, and this book is heavy with information about her own emotional needs and the shadow cast by a father who may have been amiable, funny, and suave in order to avoid discussing himself. So the portrait of happiness—or an attempt to address it—is oddly unnerving.

And was the essence of the man what he was to her in the last twenty years of his life, or was that simply—and rather movingly—the “Dad” he composed for her, his longest-running role? By now, the claims that Grant had been bisexual are as extensive as they are harmless, and they draw upon his screen persona as much as reports from others. We are talking about one of the most skilled and charismatic actors in a medium that broke fresh ground in appealing to the fantasies of every gender at the same time. You could not be a movie star without having the dream love and allegiance of both the main sexual constituencies. We are learning increasingly that that pressure (or opportunity) moved a lot of the men and women in movies toward sexual experiment, bisexuality, or gayness. And the underground influence of the movies has been a welcome force in the larger public understanding of sexual variety. The nub of Grant’s “intelligence” on screen is so often a matter of showing greater doubt than most actors of his time could admit. It is his uncertainty and hesitation that are most intriguing on screen, the pauses, the glances—at other characters, at us, at the idea of the movie—that makes him modern and enigmatic. Why shouldn’t it have a connection with a bisexual sensibility?

But Ms. Grant sounds as if she might have been pushed to say at least something by her publisher:

It’s awkward living with public misconceptions about my father. What does one say when asked if one’s famously charming, debonair, five-times-married, crooned-over father is gay? Hmmm…a grin escapes me. Can’t blame men for wanting him, and wouldn’t be surprised if Dad even mildly flirted back. If so, it manifested as witty repartee as opposed to a pat on the ass. That’s a sign of healthy, secure sexuality. Isn’t it remarkable that in this day and age anyone would seek to impugn Dad’s character with a hint at homosexuality. Being gay is neither here nor there, but hiding oneself from family and friends…not so good. When the question arises, it generally speaks more about the person asking. Of course, Dad somewhat enjoyed being called gay. He said it made women want to prove the assertion wrong. When asked if Dad was gay, Betsy Drake had the best answer: “I don’t know, we were always too busy fucking for me to ask.”

But what Betsy Drake actually said (on a TV tribute to Grant), was: “Why would I believe that Cary was homosexual when we were busy fucking? Maybe he was bisexual. He lived forty-three years before he met me. I don’t know what he did.” That seems candid and reasonable, and it allows the possibility that to call someone gay or bisexual is not to impugn them.

A larger area of neglect may help explain much else. This is how Jennifer Grant refers to her father’s early life—the years of Archibald Leach:

In terms of Dad’s pre-me life, here’s what little I know. Dad’s mom was Elsie and his dad was Elias Leach. My grandparents. He was raised an only child in Bristol, England. His father wasn’t around a lot. Dad was a troublemaker at school, and the way he described it, he liked to jump atop the wall to the girls’ locker room. In our equivalent of sixth grade, that propensity got him kicked out. Dad then found a more profitable use for his acrobatic skills. He joined the Pender Troupe, with whom he traveled to America.

This won’t do. Archibald Alexander Leach was born in Bristol to Elsie and Elias in January 1904. Apparently, the parents quarreled a good deal. When Archie was nine he discovered one day that his mother was not at home. His father told him she had gone away. The boy grew up with his father and eventually left for America. He was in Hollywood in 1935, age thirty-one, when he received a letter from a Bristol solicitor telling him that his father had died, and that there were a few legal proceedings to be dealt with. One of which was what to do with Elsie. When the mother went away the father had actually placed her in a Bristol asylum, the Country Home for Mental Defectives, at Fishponds, on account of her depression. He paid one pound a year to keep her there. It is not clear whether she was certified, or how her illness was described. But Archie had no idea whether she was alive or dead or where she might be. He had not seen her for twenty-two years. Apparently a grown-up cousin did visit Elsie and said later that she seemed well, resilient, and was asking to be let out.

Grant went straight to Bristol once he learned this news and he had his mother released very quickly—clearly she was not regarded as “insane.” In time, he brought Elsie to America but that never quite worked out. He would say, in a series of articles in the Ladies’ Home Journal of 1963, published under his name, and unmentioned by Jennifer, that Elsie was stubborn and resistant to the idea that Grant was now supporting her in the US. You can see why. So he established her back in England, in Bristol, and did all he could to look after her. But he often found her cold, and she made him nervous. There are photographs of her in this book. There is a transcript of sound recordings made at her ninety-second birthday. Jennifer met her as a child. Elsie did not die until 1973, when she was ninety-four. In one of the magazine articles, assessing the whole matter, Grant said, “There was a void in my life, a sadness of spirit that affected each daily activity with which I occupied myself in order to overcome it.”

Did the daughter read those articles? “Dad rarely if ever spoke of his parents,” says Jennifer Grant. She adds, “Almost all of Dad’s personal childhood archives were burned in World War I.” That’s why Cary Grant built a bank-strength vault in his house, 9966 Beverly Grove Drive, where he deposited all the papers and tapes of Jennifer’s life, even the sounds of silence, so that if the house burned down, the past, her record, would survive.

We don’t know what Jennifer Grant knew about this history. Her dad might not have told her, though no one could blame Archie or Cary for what happened. Of course, that has little to do with the guilt or distress the son must have felt. Did he never tell Betsy Drake, Dyan Cannon, Barbara Harris—or friends like Sinatra, Las Vegas hotel mogul Kirk Kerkorian, and Quincy Jones? Or was everyone’s pal quite lonely? As you read this book, and as you look at its snapshots of the endlessly cheery Cary Grant, you may ask, is his actual life merely being hinted at, as in a fairy tale or an opera? At the least it is a story that begins to help us understand Grant’s immaculate reticence, his poised anxiety, his eternal ambiguity on screen. Good Stuff is not a comfortable book, and you don’t have to read too far between its emphatic lines to guess at difficulties the author has had to face in trying to tell the story. “Cary Grant” was always “there,” not just loved by the camera but epitomizing our fantasy life with the screen. But to stay “there” so long you have to sustain mystery, and mystery can be hard on a kid.

This Issue

August 18, 2011

What Were They Thinking?

Fooled by Science

How Google Dominates Us