In his memoir Dreams from My Father, Barack Obama tells us that when he was a boy in Indonesia, his mother

five days a week…came into my room at four in the morning, force-fed me breakfast, and proceeded to teach me my English lessons for three hours before I left for school and she left for work. I offered stiff resistance to this regimen, but in response to every strategy I concocted…she would patiently repeat her most powerful defense:

“This is no picnic for me either, buster.”

President Obama is the evidently successful result of having had a Tiger Mother, the term made current by Amy Chua’s book Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, in which the author describes her similarly exacting approach to motherhood. Her challenging goals for her two daughters were a picnic neither for them nor for her. To get those girls to Carnegie Hall and Harvard involved hours of piano and violin practice, math and spelling drills, the expectation that they would have perfect grades, and be the best at whatever they did; and their mother was there “in the trenches,” as she says, with them. It takes self-discipline and a lot of time to be a Tiger Mother, and that’s where, according to Chua, American parents have let their offspring down.

Amy Chua is a law professor at Yale University, with two daughters whom she has raised with firmness, to say the least. That her account of some of her views and practices—standing over them at the piano for hours at a time, rejecting ill-done Mother’s Day cards or careless essays, requiring A report cards—horrified some of the wide audience for her book shouldn’t surprise. Did anyone ever admire the way other parents bring up their kids? There’s scarcely a subject more fraught with reproach and scrutiny, more fertile for theories, than parenting, and motherhood in particular. And what woman doesn’t feel a raft of guilty, vulnerable, anxious emotions about her own qualities as a mother? Fathers, no doubt, feel uncertainties too, but aren’t held to account in the same way, nor are they expected to develop a philosophy.

Chua defends hers by saying she is paying the children the compliment of assuming that they can accomplish what she demands, that they sense her respect for them, and that it’s the Chinese way. She is, after all, only perpetuating her own upbringing:

When I was little, my mother used to say, “Why do you need to sleep at someone else’s house? What’s wrong with your own family?” As a parent, I took the same position…. Sophia didn’t need to be exposed to the worst of Western society, and I wasn’t going to let platitudes like “Children need to explore” or “They need to make their own mistakes” lead me astray.

Since the publication of the book, maybe in response to the vigorous comment that ensued, she has added that it’s partly a tongue-in-cheek apology for having gone overboard, an admission that she knows she’s a little obsessive and needs to relax, and that her methods have cost her social acceptance, a lot of time, and a certain amount of family friction. And it should also be said that in the outcry around this book, many people will have read reviews and discussions of it without having read the actual text, and thus will have missed Chua’s light tone of mischievous provocation:

If a Chinese child gets a B—which would never happen—there would first be a screaming, hair-tearing explosion. The devastated Chinese mother would then get dozens, maybe hundreds of practice tests and work through them with her child for as long as it takes to get the grade up to an A.

The hyperbole disguises and to an extent mitigates the underlying seriousness of her real subject, the Decline of the West. Maybe it is this subtext that has caused people to react to Chua’s confession with unusual vehemence; she says she has received hundreds of e-mails and even death threats; people left parties when she came in. Reading a number of reviews together, one is left with the impression not so much of ire or indignation on behalf of Chua’s accomplished but overworked children, but of chagrin, the reflex of a sneaking sense that we haven’t spent enough time with our kids or helped them on to the distinctions that might have been inherent in their natures.

Among the numerous reviews, comments vary from vitriol to grudging admiration to defiance. Some readers feel that Chua should be prosecuted for child abuse, others that she is too self-involved. Everyone will notice that most of Chua’s anecdotes, so ostensibly loaded with self-reproach, also happen to showcase her familiarity with music, sports, Europe, and other languages—a picture of an accomplished, impressive if irritating person whose skills embrace, finally, loving care of husband, children, and dogs. “In truth, Ms. Chua’s memoir is about one little narcissist’s book-length search for happiness…. It will gratify the same people who made a hit out of the granola-hearted ‘Eat, Pray, Love,'” snaps Janet Maslin in The New York Times.

Advertisement

Critics predict that her children will be estranged, traumatized, spend years with shrinks, have health problems, and so on, but of course no one can possibly know the actual dynamics of any given family; generations of Americans have had ambitious parents, and often, like Obama, profited from the attention. Yet other critics think she doesn’t go far enough. David Brooks, tongue only partly in cheek, says:

I believe she’s coddling her children. She’s protecting them from the most intellectually demanding activities because she doesn’t understand what’s cognitively difficult and what isn’t.

Practicing a piece of music for four hours requires focused attention, but it is nowhere near as cognitively demanding as a sleepover with 14-year-old girls. Managing status rivalries, negotiating group dynamics, understanding social norms, navigating the distinction between self and group—these and other social tests impose cognitive demands that blow away any intense tutoring session or a class at Yale.

Ayelet Waldman, writing in The Wall Street Journal, says she allowed her kids to

participate in any extracurricular activity they wanted, so long as I was never required to drive farther than 10 minutes to get them there, or to sit on a field in a folding chair in anything but the balmiest weather for any longer than 60 minutes….

The difference between Ms. Chua and me, I suppose—between proud Chinese mothers and ambivalent Western ones—is that I felt guilty about having berated my daughter for failing to deliver the report card I expected. I was ashamed at my reaction. But here is another difference, one I’ll admit despite being ashamed of it, too: I did not then go out and get hundreds of practice tests and work through them with my daughter far into the night, doing whatever it took to get her the A. I fobbed that task off on a tutor, something I can afford to do because my children reside in the same privileged world as Ms. Chua’s.

Asian-Americans seem especially infuriated. Betty Ming Liu blogged on January 8 about “lunatic, prestige-whoring Chinese parents” with “values that have nearly ruined so many of us…. Haven’t we had enough of over-pressured, guilt-ridden Asian immigrant and Asian-American college students committing suicide and acting out???” Wesley Yang, writing in New York magazine, sums up his “feelings toward Asian values: Fuck filial piety. Fuck grade-grubbing. Fuck Ivy League mania. Fuck deference to authority. Fuck humility and hard work….” He reminds readers that no matter how accomplished an Asian-American is, there’s still a bamboo ceiling after graduation.

Why has this book excited such extreme reactions? It’s not as if Chua is advocating female circumcision or corporal punishment; her thesis shouldn’t really shock. Most people accept that differences among cultures and parental assumptions exist. And besides cultural influences, most people survive some form of parental eccentricity, the stuff of eventual memoirs; one of my childhood friends was given almost daily enemas according to some then-prevalent Scandinavian theory of hygiene.

There are simple differences in family rhetorical conventions. I remember years ago reading Maxine Hong Kingston’s Woman Warrior and being shocked that her grand-uncle called girl children “maggots,” something she doesn’t remember with special pain today. According to Chua, all Chinese parents make use of shame, call their kids “fatty” and “garbage,” and much worse, and the kids understand it as being within the boundaries of the family’s chosen level of diction: it’s just the way mom talks. When such talk seems excessive to her fellow guests at a dinner party, Chua says, “It’s a Chinese immigrant thing.” Someone points out that she isn’t a Chinese immigrant. “Good point,” she concedes. “No wonder it didn’t work.”

She explains her apparent harshness more as a difference in expressive style: “It’s not that Chinese parents don’t care about their children. Just the opposite.” They don’t worry as Western parents do about self-esteem, and they think their children can take criticism. “They assume strength, not fragility, and as a result they behave very differently.” “As a parent, one of the worst things you can do for your child’s self-esteem is to let them give up. On the flip side, there’s nothing better for building confidence than learning you can do something you thought you couldn’t.”

Advertisement

“Chinese” in Chua’s lexicon basically signifies any motivated and disciplined subgroup competing with the tired, ineffectual mainstream. At other periods in American history we could have substituted the name of some other ethnic minority. Some of the anxious comment on her book may be connected to our apprehensions about China. If Chua had written The Battle Hymn of a Nigerian Mother would our reaction be the same?

The child of immigrants, Chua herself fits into a traditional American pattern: immigrant parents, high-achieving children, a more relaxed third generation often becoming artists or filmmakers—or musicians or tennis players, like her daughters Lulu and Sophia.

In raising them, Chua directly challenges the prevailing Western orthodoxies, in place since Dr. Spock, or even since Freud, that hold that repression breeds psychological problems, and that freedom and creativity are intertwined—but do we really believe those orthodoxies anyhow? She thinks that American kids waste too much time and expend too little effort, and the same goes for American parents. She has a lot of evidence for this—grade inflation is one result, the poor performance of American students on internationally competitive tests is another. The poor performance of Caucasian, African-American, and Hispanic students within our school system is another. The University of California relaxed some grade-dependent admissions policies, which had been strictly color- and gender-blind, because the university was filling up chiefly with Asians.

Internationally, Americans rank far below European and Asian students on some measures—thirty-first in the world in math, for example. There are no measures, by any of the most important tests (OECD, McKenzie, US Department of Education), in which the US excels, or even does better than average in any subject, and in some subjects (math), American students do far worse than average, despite the fact that we spend more money per pupil than almost any other country.* And this is a nation that thinks of itself as number one. Chua sneers a little at unwarranted self-esteem:

Western parents try to respect their children’s individuality, encouraging them to pursue their true passions, supporting their choices, and providing positive reinforcement and a nurturing environment. By contrast, the Chinese believe that the best way to protect their children is by preparing them for the future, letting them see what they’re capable of, and arming them with skills, work habits, and inner confidence that no one can ever take away.

To impart these advantages takes a lot of parental—usually maternal—time. Here is Chua’s description of supervising Sophia’s piano practice:

I broke the Rondo down, sometimes by section, sometimes by goal. We’d spend one hour focusing just on articulation (clarity of notes), then another on tempo (with the metronome), followed by another on dynamics (loud, soft, crescendo, decrescendo), then another on phrasing (shaping musical lines), and so on.

The child suffers through these hours, but eventually receives praise, admiration, pride, and indeed enjoyment when she gives a great performance. It doesn’t escape us that, unlike most of us, Chua herself has boned up on piano phrasing, and how to shift from first to third position on the violin, and probably entrechats and pliés and calculus and The Return of the Native—whatever in the way of special knowledge it takes to help the children excel. In other words, Chua (despite having a job on the law faculty at Yale) is putting in major time and effort herself.

It’s here that self-interest possibly sullies the convictions of those who object that Chua’s kids don’t have any time to develop, to mess around, to “individuate”—only a few of the objections to Chua’s mothering. You can’t get around the fact that to let kids individuate by themselves is a lot easier on you, and since, like Ayelet Waldman, most parents don’t even have time to put in the required hours, Chua gets a lot of grudging points for her stamina and commitment.

Are there studies comparing the results of commercial preparation—paid tutors, cram schools—with the results of parental tutoring? No doubt it’s more emotionally complicated to have your parents urging you on. And is it efficient for society to depend on the unpaid labor of parents who are also highly trained professionals, who could be spending their time at their professions? These are unanswered questions.

If we’re old enough, we’re aware that parenting philosophies swing from authoritarian to permissive and around again with the decades. Shifts in parenting orthodoxies are roughly related to political climate—the Sixties, with its general relaxation of mores, produced the genial and trusted Dr. Spock, whose counsel was directly opposed to China: “too often parents make poor tutors…because they care too much and become too upset.” People who during the same period disapproved of hippies blamed their loose morals on either the repressive parents they were rebelling against or permissive parents who “let them get away” with things. The whole business of blaming parents for the flaws of the children also dates, more or less, from Freud, as we know; in antiquity and Shakespeare, people were responsible for their own characters, unless some god intervened.

American unease or outright discontent with teachers and educators is another factor propelling the debate around the Tiger Mom. If there is ire against Ms. Chua, it is also related to widespread unhappiness with the American educational system, especially its teachers. Why are our kids falling behind? We have a system that is not educating them the way we want it to, and not up to the mark we used to expect; but we lack the political ability to change it and the energy to substitute our own time for it, and the will to pay more. And we’re alarmed at the suggestion that education is a do-it-yourself enterprise—what are we paying the teachers for? Though the US spends a slightly larger percent- age of its GDP (7.6 percent) on education than any of the other countries with which we are compared except Iceland (7.8), we get less for our money, and are average or below the average of OECD nations, around twenty-fifth in most subjects, but not so far behind England, Germany, and France.

Most of us know that whatever we are doing is probably wrong and that the parents of our children’s friends are also inevitably too lenient or too strict. Many of us eventually fall back on instinct, hopefully improved by resolve, to emulate or refute the practices of our own parents, probably with the results predicted in Philip Larkin’s poem, but with some results to be proud of too, when your kid gets a prize or does something handsome for someone else or speaks politely to your guests, surprising you with some evidence of his good upbringing.

If Chua sees parenting mechanically, as a sort of physics of behavior—work + time = score—we would like to think it isn’t as simple as that. But she’s worth attention. Studies of why Asians do better in school find that the leading factors are parental involvement, study habits, and time spent. Chua makes a case for parents getting some credit, but anyone who has raised children also knows that despite whatever parenting they’ve received, their individual natures count for a lot.

Chua, however, has a wider subject, the one that probably really accounts for much of the anxious reaction to her book: America—its decline in power, its degenerating character and resolve, its new second-rateness. Chinese Tiger Mothers are emblematic of the rise of China itself, and enforce our sense that our response to it is probably inadequate; and, moreover, China stands for the rest of the world too, everywhere that we are slipping behind and others are rising.

In two earlier books, Chua has given her views on American decline a fuller treatment, with a brisk, clear-eyed, somewhat superficial, but convincing analysis of its causes and probable consequences—she is sort of the Malcolm Gladwell of geopolitics. Some people do see things in clear, binary terms. Though Chua does not speak Mandarin, they say that the Mandarin language tends to put things that way, as in yin and yang, or with sayings like you fan chi (有 飯 吃), meaning you have rice or not, meaning you have a livelihood or not, you got an A or not.

In her view, besides being naive about its situation, America is doing a lot to make its situation worse. Her first book, World on Fire: How Exporting Free Market Democracy Breeds Ethnic Hatred and Global Instability (2003), holds that “market-dominant” minorities in every culture incite the resentment of the poorer majority with sometimes bloody consequences (Rwanda-Burundi); and because the US is the ultimate market-dominant minority (for the moment), it is the most widely hated. Her thesis is supported by a lot of examples, beginning with the murder of her rich Chinese aunt by the native servants in the Philippines, where Chinese own a large percentage of the wealth. The cure is to keep a lower profile and be more generous with money and know-how in helping other economies to rise.

More recently, in Day of Empire: How Hyperpowers Rise to Global Dominance—and Why They Fail (2007), she argues that empires grow and dominate in periods when they are tolerant of religious and ethnic diversity, and doom themselves when they become sectarian and exclusive. There are many examples to support this thesis also, for instance the Dutch in the seventeenth century, whose famous tolerance did not extend to their imperial subjects, or the Ottoman Empire, generally assimilative until outside menaces and the incompetence of Suleyman’s successors drew it into religious schism.

Chua’s warning for the US is that without a means of forging a common political identity to bind other peoples to us, “the United States would be better off following the formula [of inclusion] that served it so well for more than two hundred years.” “America pulled away from all its rivals by turning itself into a magnet for the world’s most energetic and enterprising; [and] by shrewdly avoiding unnecessary, self-destructive military entanglements,” she writes, in favor of remaining the City on the Hill and trying to infuse others with a sense of shared identity and common purpose.

Her ideas can be reduced to pithy sound bites, and the remedies boil down to just doing the right thing, in the moral sense; and remembering that even if an action is in one’s own self-interest, this doesn’t mean it isn’t right. The trouble is, there is no broad agreement on such matters as immigration policy, a key ingredient of being a “magnet”; meanwhile we are shutting out graduate students from other countries and deporting talented people, adopting sectarian and intolerant attitudes that signal our decline.

The analogy of child-rearing to our national situation is clear enough: just as American parents are too concerned with “self-esteem” without basing self-esteem on an actual accomplishment that would take too much personal parental input, time, and money to acquire, so our entire culture operates on some notion of natural rights that is no longer realistic. Chua’s point is that a delusional culture based on unearned self-esteem can’t for long be a realistic player in global competition for influence, power, and resources. Is it possible that we should mind our Tiger Mother?

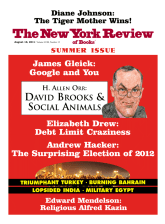

This Issue

August 18, 2011

What Were They Thinking?

Fooled by Science

How Google Dominates Us

-

*

See OECD education statistics, National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), the US Department of Education, and many other available statistics bearing on US rankings. ↩