1.

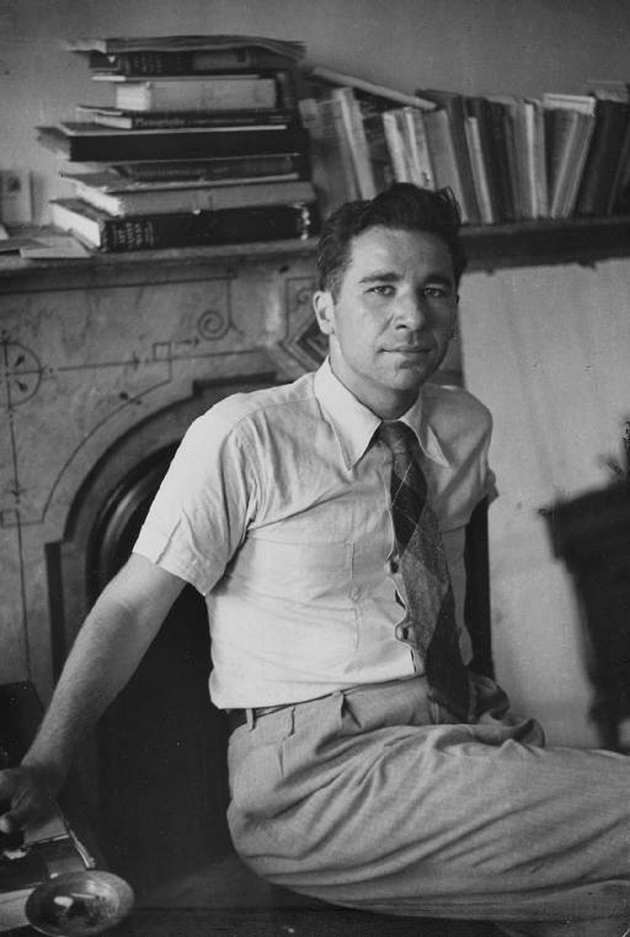

Alfred Kazin’s Journals is a profound and exciting book, more so even than the best of the dozen works of criticism and autobiography that he published during his lifetime. Almost every morning from the age of eighteen, in 1933, until his death in 1998, he wrote his private thoughts about literature, history, the social world of publishing, universities, and politics, his four marriages and uncountable affairs, the “many people I know and admire, or rather love,” and what it means to be a Jew. He wrote sometimes as a literary and erotic conqueror, sometimes as a guilty victim of conscience, always with infectious intellectual energy.

Kazin climbed from a Jewish ghetto in Brooklyn to the sudden fame of his book about American writing, On Native Grounds (1942), to the literary editor’s desk at The New Republic, where he followed Edmund Wilson and Malcolm Cowley, and on to the success of his memoir A Walker in the City (1951). By the 1960s he was the most powerful reviewer in America, passing judgment in The New Yorker and the Sunday book reviews, and in more than sixty essays in these pages. As he recorded in his journals:

The beggarly Jewish radicals of the 30s are now the ruling cultural pundits of American society—I who stood so long outside the door wondering if I would ever get through it, am now one of the standard bearers of American literary opinion—a judge of young men.

Dag Hammarsköld asked him to lunch at the United Nations. John F. Kennedy asked him to lunch at the White House after learning that Kazin was writing an essay about him. Kazin, unimpressed, portrayed Kennedy as a charmer without substance.

Readers expect revelations from a posthumously published journal, and this one does not disappoint, though the secret it reveals has no shock value. From adolescence onward, Kazin was engrossed in a spiritual and sometimes mystical inner life that he never talked about. None of his friends or lovers seems to have been aware of it. It was far more hidden than his notoriously florid erotic life. Much of what he had to say in his essays about other people’s religion was secretly about his own, especially when he described an inner faith that rebelled against all churches and doctrines. He wrote in An American Procession (1984):

Emerson was beginning to understand that total “self-reliance”—from his innermost spiritual promptings—would be his career and his fate.

The same thought prompted his journal entry: “Emerson made me a Jew.”

The journals make clear that his long introduction to The Portable Blake (1946) was a disguised self-portrait, with Blake’s Christianity standing in for Kazin’s Judaism:

[Blake] was a libertarian obsessed with God; a mystic who reversed the mystical pattern, for he sought man as the end of his search. He was a Christian who hated the churches; a revolutionary who abhorred the materialism of the radicals.

Kazin’s best-known essays in his later years were political jeremiads against neoconservative arrivistes who identified their own success with eternal moral truths. As his journals reveal, in this he was driven by his own religious sense of what an eternal truth might really be—something demanding, uneasy, uncompromising.1

He returns again and again to one central question: how to be a free individual, untempted by convention or ideology yet morally responsible to the unknowable source of all value that it was convenient to call God. “God is only a name for our wonder,” he wrote. “We know that supernaturalism is a lie, and therefore miss its truth as myth—as the theory of human correspondences,” by which he seems to mean the unseen ways in which individual lives are connected to the larger world. “I am a religious,” he writes, using “religious” as a noun like the French un religieux:

I do not believe in the new God of Communism or the old God of the synagogue—I believe in God. I cannot live without the belief that there is a purposeful connection that I may yet understand which I can serve. I cannot be faithless to my own conviction of value.

His pursuit of value and belief takes him to the depths of his private self. “The only meaning of religion is revelation—that is, the meaning and worth of religion come to self-knowledge.” His compulsion to keep a journal “is very mysterious,” because he writes about himself, but for “someone who is not altogether ME”:

There is a deeper part of myself than the ordinary wide-awake and social one that I strangely satisfy by the freedom I feel in writing this. Some older part of me, anarchistic and spiritually outlaw—that does not have to answer to anyone. Yet demands that I foster it, engage it all the time.

In some of the most moving passages in this book, Kazin returns to his memories of walking among the London crowds in 1945, when Labour won the election, and he sensed that self-knowledge has its roots in shared, unconscious experience:

Advertisement

Society, a mass, acting in concert with you, expressing the deepest part of you, the unconscious part of you, in fact (just the opposite of being submerged in the crowd). This is the positive sacramental side of society as an institution: working for you, with the energy and unconscious but positive wisdom that you do not immediately find in yourself.

Kazin’s journals portray him, unexpectedly, as Emerson’s Jewish heir. But he integrated Emersonian self-reliance with socialist sympathies learned from the Labour Party and the London crowds and a visionary mysticism inspired by William Blake.

2.

“Values are our only home in the universe,” Kazin wrote in 1962 at the height of his public success, and the more intensely he thought about values, the more intensely he thought about himself as a Jew. “For what is it I draw my basic values from if not from the Jews!” His journals explore a radical, idiosyncratic Judaism informed by the same nonconformist moral passion that drove Blake’s radical, idiosyncratic Christianity.

Kazin follows a long tradition in seeing messianic hope as the core of Judaism. “Jews who do not believe in the Messiah…are like everyone else and as a tribe not particularly interesting.” But he has no interest in literal or supernatural beliefs. His messianic faith is his belief in the invisible reality of value and meaning:

The hidden God. My God is no God shining on an altar in a nimbus of gold-painted spikes, but the hidden God, the God that waits to be disclosed, as we wait—to find him. Between Him and me what silence, what long preparations and rehearsals, what a deep shyness.

All other forms of Judaism are mere vanities. Jews who focus on their collective identity, who ignore “the remote deeps from which their God comes,” make Judaism trivial or worse. A Jew must be an outsider, even to Judaism:

Every original Jew turns against the Jews—they are the earth from which his spirit tries to free itself…. The vice of Jewish solidarity—it is an unexpressed2 compassion without love. The glory of being in the truth, Jewish or not Jewish, is to find a love higher than solidarity.

Jewish solidarity sustains itself through the conceit that exile and persecution, not faith, define a Jew. The sense that Jews have of themselves

as special cases, as an importunate and eternally aggrieved minority always,…puts them into the position of consciously amending justice and truth in order to get their human rights in…. The more the Jews regard themselves as special cases,…the more they keep themselves from achieving this moral centrality, their perspective on the whole human problem, which is their birthright, their privilege, and their real history.

His problem, “as always, is how to be a ‘Jew’ without ‘Judaism’—how to live…without simply becoming a worshipper: by which I mean someone bent to this cult.” What matters about belief is the individual moral commitment that drives it: “not the creed, but the believer.” The brief, transforming papacy of John XXIII inspires him to a “sense of moral liberation.” John’s “personal faith” gives him a renewed sense that the future is shaped by voluntary moral choices, not by the impersonal force of history:

I am more and more convinced that this dimension of personal freedom…is decisive. Only this individual sense of good and evil can abolish the pathetic sense of being a disappointed spectator and onlooker, a reader of the historical fortunes.

“God is born of loneliness,” he writes in a meditation on Melville. The “sense of good and evil” is a universal truth that can arise only from deep private sources—unlike all impersonal generalizations that can be abstracted into a general principle. “The first thing a principle does nowadays, if it is really a principle, is to kill somebody.”

In 1962, reading a book of documents of the Nazi destruction of the Warsaw ghetto, Kazin is appalled by a Jewish religiosity that found divine meaning in mass murder:

Jewish submission, Jewish passivity and quietism. It’s as if the phrase used in the ghetto for death at the hands of the Nazis—Kiddush ha-shem, sanctification of the [divine] name—expressed the distraction, the God-intoxication, that made everything else unworthy…. Is it really true…that the Jews see themselves (ultimately) as a kind of sacrifice in the divine process of creation?… The desired condition—pride, resistance, dignity—how is this made impossible by sanctification of the divine name? To believe in the Jews as a necessary sacrifice is to express a nearly Oriental fatalism. In this view the human being is actually held in contempt by God, is nothing to Him, merely exists to demonstrate His greatness.

What he says about Jewish history is also a response to his family history, to “the anxiety that has been the background of my life, reflected in my parents’ insecurity and panic.”

Advertisement

The Jews were chosen “to teach all around them the inexpungeable memory of the divine source from which our lives come.” That mission, he believed, could be carried out “only in the diaspora, for among the nations they served to remind the world of the transcendent source and meaning of this experience.”

As a state they can only misuse, exploit, and even kill this mission…. It becomes increasingly clear, as “Israel” ceases to be a faith and becomes an ideology, that Christianity alone does justice to the historic mission of the Jews—that it is only as Christians that Jews can remain Jews.

He draws back after writing this, unable to imagine giving up his Jewishness, and adds that a Jew who becomes a Christian “ceases to be a reminder” because he has been “swallowed up in the general community of faith. So the Jew must remain in the diaspora….”

To live authentically as a Jew, in Kazin’s eyes, is to serve universal justice, to refuse all partisan, tribal, and ideological causes, including those that claim to be Jewish. On Thanksgiving Day, 1988, he writes about “the cry for justice” that rose from the homeless in Depression America and from the Jews in Nazi Germany. But justice is a task for the present, not the past:

It is plain just now that the cry for justice that comes up very powerfully from Arabs in the occupied territories—and for which over 250 people, many of them young people, have been killed by Israeli army and police—that their cry for justice is certainly louder than that of Defense Minister Rabin talking about the early struggle of Labor Zionists.

The moral individual looks toward the future. “The Christian idea of the future—based on the individual. The Jewish idea: the past, the group.” The Jewish past serves all too easily as a resource to be exploited by the unjust:

A Congressional Gold Medal to Elie [Wiesel]—the whole thing is beginning to stink to high heaven as the most shameless personal aggrandizement in the name of dead Jews.

Meanwhile, he sees “the American Jewish Committee publishing one of the most reactionary magazines in America [Commentary], and one which only recently practically justified some of the Nazi murderers among us because of their intense anti-Communism.”

3.

In Kazin’s journals, an authentic writer and an authentic Jew are much the same. Both are outsiders, not “outsiders and victims merely,” but individuals who make judgments based on personal commitment and belief. Both revolt against ideology and convention; both long for absolutes. Kazin loves any writer in whom he sees “the literary radical, the pure Protestant spirit—the individual as consciousness.” He is awed by “the terrible and graphic loneliness of the great Americans,” Emerson, Melville, Whitman, Dickinson, James, Frost, Dreiser, Faulkner, Hemingway:

Thinking about them composes itself, sooner or later, into a gallery of extraordinary individuals; yet at bottom they have nothing in common but the almost shattering unassailability, the life-stricken I, in each. Each fought his way through life—and through his genius—as if no one had ever fought before.

He asks whether his excitement is the effect of his Jewishness: “Is it—most obvious supposition—that I am an outsider; and that only for the first American-born son of so many thousands of mud-flat Jewish-Polish-Russian generations is this need so great, this inquiry so urgent?” Here, and intermittently elsewhere, he writes as if the Jews were the world’s only outsiders and that he is one of those “special cases” that, in his more thoughtful moments, he reminds himself they are not.

The writer who most inspires him to reverence is Hannah Arendt. In 1963, after reading Eichmann in Jerusalem —a book that echoed his dismay over Jewish passivity—he sets her down as “one of the just…. She holds out, alone, for basic values.” Her sense of justice “is the lightning in her to which I always respond.” The charged word “gift” recurs in his thoughts about her: “the Jewish intellectual’s gift, to see the Christian-liberal-‘classical’ world from the outside…Hannah’s gift—even when [she] speaks in ‘classical’ accents.” She is a priestess of his radical Judaism:

When I read her, I remember, for a brief instance, a world, another world, to which we owe all our concepts of human grandeur…. Without God, we do not know who we are. This is what she recalls to me, and for this I am grateful.

He reveres some, not all, of Saul Bellow’s novels. Henderson the Rain King “was bad,” but Herzog “overwhelms me” and Humboldt’s Gift “amazes me all over again.” Like other great Jewish intellectuals, Bellow sees the world socially from the outside and morally from its center:

This centering in book after book on the individual comes from Saul’s sense of himself deriving from the free powers of the universe (the Jewish “God”) and from the ability to use the whole social machinery as subject. Emerson spoke of Nature and the me—everything outside me being the Not-Me…. Saul regards the American society as one form that the universe happens to adopt in this hemisphere—and it is the Not-Me.

He is less awed by Bellow the man, “a kalte mensch, too full of his being a novelist to be a human being writing,” and “congested in his usual cold conceit.”

Jewish writers and intellectuals go wrong, in Kazin’s eyes, by corrupting the “free powers of the universe” into instruments of their own power. When Norman Mailer wrote about sex, “he betrayed the Jew in him” by transforming a great mystery into a means of “world revolution, ideology, mastership through ‘idea.'” The worst betrayers of the Jew inside themselves were the ex-radicals—Norman Podhoretz, Irving Kristol—who now, he writes, proclaim their triumphal servility to right-wing politicians who dislike Jews but are happy to make use of them.

Too often in this book, Kazin returns from a cocktail party, lists everyone who was in the room, and eviscerates each with a sharp adjective. He is more surprising and convincing when he focuses on individual writers and either praises their moral integrity or condemns them as ideologues and time-servers. John Dewey is generally taken by others to represent “the pragmatic adaptable 20th-century intelligence which was going to fit philosophy into a new age”; but Kazin admires him as a nineteenth-century hero who “proved that a man can give his whole devotion to the academic career and its responsibilities, and make of it a great moral and intellectual example.” Mark Van Doren, the poet and critic who taught Kazin at Columbia, was widely revered. Kazin had a different view:

Twenty years ago…Mark Van Doren was my beau ideal…. It is a token of my growth…that Mark Van Doren now inspires me with contempt and disgust. No poet, a safeguarding, pursy3 little man forever congratulating himself in rhetorical little phrases on the right way to live and the right way to think.

(As it happens, I came to more or less the same view of Van Doren after reading an edition of his letters for a university press that chose not to publish them.)

4.

Often in the first half of this book, less often in the second, Kazin writes in praise of “my honesty and my gift for judgment.” Whenever he invokes his own “passion and exactitude and purpose,” he sounds like Tennyson’s Ulysses, proudly reminding himself that he is

strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and

not to yield.

Like Ulysses, when Kazin writes in this mood he neglects to ask what he is striving for and hopes to find, a neglect that opens him to intellectual and erotic torments.

“All my life,” he writes at forty, “I have been seeking…what may be called the individual strength, the core of maturity, the power to be strong and free inside oneself.” He begins to sense why he hasn’t found it:

More and more, it is clear to me that what I suffer from is the lack of a working philosophy, of a strong central belief, of something outside to which my “self” can hold and, for once, forget its “self.” …My besetting weakness: an inability to stay with the subject, to devour it through and through.

He never gives up “hope that my inside narrative will yet come to something!!” At seventy-one, he writes: “I work with separate pieces of stone, piece on piece on piece! But I will get the building built.”

Kazin’s essays about other writers tend to be stirring but oddly forgettable. He feels impelled more to report his excitement than to pause to understand the book or writer that provoked it. He is nearly fifty before he confronts what he calls

my tendency as a writer and critic to dwell on the “high-points” of a text, the emotional peaks, the “isolated beauties,” instead of the argument of a book. My weakness as a literary scholar and as a writer is to opt for the creative moment rather than for the argument. But only the argument settles anything in a book….

In an earlier entry he had written about “my compulsive need of books, the silent question I ask of myself when I turn to a new one: is it with this that I will be complete at last, lose my long fear of being found out?” This seems to have been the same question he asked himself on meeting a woman, and suggests what he was seeking through his compulsive need for affairs.

When he writes about sex, Kazin forgets everything he knows about individuality. He doesn’t want an individual woman. He wants the “secrecy in a woman” that is “the most vexing and yet the most delicious aspect of the feminine principle. It is to this that I make love, and will never be tired of making love.” He writes this at thirty-four. He still believes it at fifty-three, when he thinks about a woman’s wish to be loved for herself: “How can one explain to her that it is Woman one loves, the feminine principle as the necessity to gratification….” When he recalls his sexual excitement with a wife or lover, he writes as if he had made love not to herself but to her body parts. Finally, at sixty-three, he takes a different line: “The Fool could have learned more from completely loving one woman than he has ever learned skipping from book to book, life to life.” He had recently met the woman with whom he made his fourth—and his only successful—marriage.4

5.

Much of Kazin’s journal is intellectually and morally splendid; some is exasperating. Richard M. Cook’s commentary and notes are similarly divided between virtues and faults. Kazin portrays himself as thinking and writing with titanic force, even when he weeps in despair; Cook helpfully notes that others found him shy or gauche or a “Holy Schlemiel.” He also points out that some of the views that Kazin expressed in print about Jewish matters were more publicly palatable than the ones he confided to his journal.

All literary editions are disfigured by mistakes, but this one has many that could have been avoided. Kazin’s misspellings of names are repeated without comment in the notes. Some allusions to his reading and writing are identified; others are left bafflingly vague. Widely documented persons and organizations are either misidentified or unidentified or noted only as “Unknown reference.” Someone at Yale University Press could have pointed out that Chester Kerr, identified by Kazin only as an “editorial jerk,” had once been its director.

When a journal includes, as this one does, attacks on persons who are still alive at the time of publication, an editor is obliged to use discretion when choosing which entries to publish or omit. A living person’s work and thought are always legitimate targets for criticism; a living person’s physical appearance is not. Cook was right to include Kazin’s outbursts at the “brutal, little mind of Norman Podhoretz,” because Kazin was responding to books that Podhoretz chose to publish and opinions that Podhoretz was free to change. He was wrong to include Kazin’s outburst at the aging face of another writer, because her looks were not the product of moral or intellectual choices that would justify a critical response.

This six-hundred-page volume contains one sixth of Kazin’s surviving journals. A few hours spent with the manuscripts and typescripts in the New York Public Library make a convincing argument for a complete edition to be published at some future time when nothing need be omitted for the sake of living persons. Some of Kazin’s journals reveal only their author’s private darkness, but far more of them open onto vistas of literature and history illuminated by his intelligent excitement.

This Issue

August 18, 2011

What Were They Thinking?

Fooled by Science

How Google Dominates Us

-

1

Only a few traces of Kazin’s religious interests appear in A Lifetime Burning in Every Moment (1996), a book misleadingly subtitled “From the Journals of Alfred Kazin.” Much of it was rewritten or newly written, and it presents a different self-portrait from the one in Alfred Kazin’s Journals. ↩

-

2

“Unexpressed” seems to mean “not expressed in personal feeling.” In print and in his journals, Kazin often chose a vague word when he was too excited to find a more exact one. ↩

-

3

As the editor of the journals suggests, this seems to mean “like one who purses his lips.” ↩

-

4

Kazin’s account of his volcanic third marriage to Ann Birstein describes the same events that she does in her minimally fictionalized novel about him, The Last of the True Believers (1988). (The title refers to a naive, literal belief that Birstein seems to imagine he arrived at.) They agree that the sex was thrilling and that both were unfaithful. They disagree about everything else. When Kazin encounters someone, he is excited either to admiration or to fury at being denied something to admire; when Birstein meets the same person she is piqued to bored contempt. Kazin’s Hannah Arendt is a learned, visionary genius; Birstein’s is an unreadable academic snob. ↩