Someday people will look back and wonder, What were they thinking? Why, in the midst of a stalled recovery, with the economy fragile and job creation slowing to a trickle, did the nation’s leaders decide that the thing to do—in order to raise the debt limit, normally a routine matter—was to spend less money, making job creation all the more difficult? Many experts on the economy believe that the President has it backward: that focusing on growth and jobs is more urgent in the near term than cutting the deficit, even if such expenditures require borrowing. But that would go against Obama’s new self-portrait as a fiscally responsible centrist.

Lawrence Summers, Obama’s recently resigned chief economic adviser, said on The Charlie Rose Show in July that he found it “dispiriting” that “all of the energy is on the projected deficits…when the problem right now is that the economy is in danger of stagnating from lack of demand.” The Republicans had made it clear for months that they would use the need to raise the debt ceiling as an instrument for extracting concessions from the Democratic President in the form of more cuts in federal programs. And the President assented to their premise, but only if there should also be some additional revenues. Were they all insane? That’s not a far-fetched question.

The President argued that it’s critical to make cuts that will “get our fiscal house in order,” so that the American people and the politicians would accept the idea of new programs leading to growth and more jobs. But there are numerous indications that the public is ready for such programs now, and serious analysts see no reason why he should not also be taking such steps now, even if this increases the deficit in the short run. But that would be at odds with Obama’s current self-portrayal. People who are looking for work, or worried about their unemployment insurance, or getting their kids to college, may not be impressed with the argument that they must be patient while the President adjusts his fiscal image in time for the 2012 election.

Since the President wanted to cut spending but also increase taxes and the Republicans insisted on cuts with no new taxes, they were for months too far apart to find much agreement on a budget plan to be attached to the debt ceiling increase—which had to be enacted by August 2 to avoid a default. No one could quite believe that this would happen, because it was so unthinkable; it was assumed that the two parties would reach agreement. Each side actually expected the other to be more flexible. The Republicans assumed that the President would be pliable; the Democrats didn’t expect the Republicans to be so inflexible about raising taxes.

It didn’t turn out that way. The Republicans were actually divided—the older guard against the Tea Party. But this old guard was by nature further to the right than the former old guards, and the Tea Party drove it further right still. The Republicans adopted their partly ideological, partly fearful, position that none of the reductions in projected deficits could come from increased tax revenues. The President agreed that tax rates would not be raised—though they are at their lowest level in sixty years, since the presidency of Harry Truman. The administration and other Democrats had thought that it would be easier to remove some tax breaks from the tax code.

The Republicans, with Alice in Wonderland logic, termed any elimination of a tax break a tax increase. Moreover, the breaks included in the tax code were there because they had been sponsored by an important member of Congress, or supported by a powerful lobby on behalf of one interest or another. After the President, in a press conference in late June, inveighed against tax breaks for corporate jets, the industry quickly insisted that such a change would cost jobs.

The very basis of the negotiations was odd. A vote to raise the debt limit simply validates spending decisions that had already been approved by Congress, and it is usually automatic. It does nothing to curb spending. But there is nothing usual about the current Congress. The recent negotiations over raising the debt limit could have been seen as having an absurd, antic quality, if they hadn’t been so risky to most people living in this country and so unfair in their potential impact on the various income groups, with consequences, too, for the global economy. The negotiations were ridiculously contorted—when one side refused to discuss a major topic, such as taxes, were they actually negotiations at all? Similarly, Democrats balked at serious cuts in entitlement programs. So there was a standoff.

Advertisement

As August 2 approached, the possible effects of default should have become familiar to anyone paying the slightest attention. The particulars had been recited, and published, over and over again by the President and some officials in the hope of scaring the members of Congress or their constituents. They spoke of not enough money being available after interest on the debt was paid. There might not be enough for popular programs such as Social Security or Medicare or veterans’ benefits—of which just about everybody was either a beneficiary, or knew or was related to someone who was. As the possibility of default grew near, the President wasn’t above warning that he couldn’t guarantee that Social Security checks would go out. There were predictions of rising interest rates and Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner spoke of a second recession.

These warnings did result in a shift of opinion in mid-July in favor of lifting the debt ceiling. Standing against them were the countless number of people who didn’t believe anything the federal government said, and their know-nothingism was reinforced by opportunistic political figures. The self-appointed head of the congressional Tea Party and presidential candidate Michele Bachmann made denial a major part of her campaign: “Don’t let them scare you by telling you that the country’s going to fall apart.”

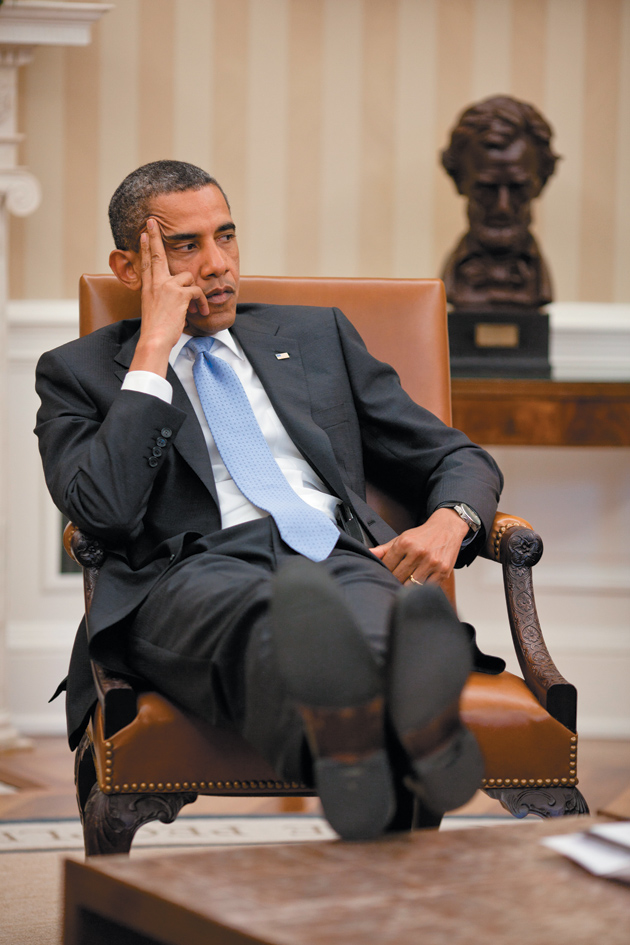

Thus the year 2011 had come to be dominated by the Politics of Calamity. There was a pattern. In the spring, with the threat of a government shutdown for the rest of the fiscal year, the Republicans, with the Tea Party representatives in the lead, had set the terms of the debate over a continuing resolution. They backed the President—who in his eagerness to establish his credentials as fiscally responsible hadn’t engaged them in a fight—into a corner. Obama and House Speaker John Boehner engaged in frantic negotiations at the White House. What these two men had agreed on wasn’t known for days, as aides scrambled to figure out what they had decided. Finally a continuing resolution was passed.

Months later, with the threat of a government default if the debt ceiling was not raised by August 2, the Republicans once again seized the agenda and demanded that there be a ten-year budget with major spending cuts. The President had yet to put forward a serious long-term budget of his own. The regular legislative process was then superseded by policy being made, in a room out of sight of the press and the public, by negotiators facing the threat of the United States government going into default. It takes the threat of something awful happening to drive the politicians—fearful of the effect on their careers—to bring deliberations to a close.

The hitch was that Republicans chose to use the statutory increase in the debt limit—by about $2.2 trillion on top of a $14.2 trillion debt—as a lever to exact more cuts in spending, from funds that had already been authorized or even spent. In a speech on May 9 before the Economic Club in New York, John Boehner advanced the novel theory that every dollar by which the debt ceiling was increased had to be offset by cutting a dollar in spending.

The Tea Party’s strength was larger than its numbers—about eighty in the House and as few as four in the Senate—because the entire House Republican freshman class and some more senior members were sympathetic to its views, and because the ghost of Bob Bennett now haunts many Republicans. Bennett (still alive), a solid conservative three-term senator from Utah, was, astonishingly, rejected for reelection last year by the Utah Republican caucus for having been insufficiently pure in his conservatism. (His vote in 2006 against a constitutional amendment to ban flag-burning was seen as heresy.)

If Bob Bennett could be dumped, no one was safe. Boehner himself was facing a possible primary challenge. Some Tea Party members dug in on the debt ceiling because they, too, feared attacks or challenges, principally from people who would accuse them of not forcing sufficient cuts or of failing to keep their pledge not to raise the debt limit.

The Republicans embraced a philosophy of no new taxes or revenues that had little relation to reality—except for the fact that their long-standing goal has been to shrink the size of the federal government. This began with the major tax cut passed early in George W. Bush’s presidency, which purposely put serious pressure on domestic programs and which some saw at the time as folly—folly with grim implications for the future.* That tax cut, renewed in December with Obama’s assent (he didn’t have the votes to stop it, and he got some stimulus money in exchange), began the Republicans’ march from the $137 billion surplus Bill Clinton had bequeathed the country to the deficit of $1.2 trillion when Bush left office. It accounts for more than one quarter of the current deficit.

Advertisement

Obama’s proposal to end the Bush tax cuts for those making over $250,000 was of course not expected to go anywhere, especially in the House. That left tax expenditures—or “loopholes” permitting tax deductions. But when, on June 23, the Democrats offered their list of revenue-raising possibilities in the bipartisan talks presided over by Vice President Joe Biden, House Majority Leader Eric Cantor dramatically walked out. The bipartisan group had already agreed to over $1 trillion in spending cuts, but this was contingent on increasing revenues as well. Cantor’s abrupt exit was generally interpreted as an act intended to keep his fingerprints off any revenue increases. He would leave that to Boehner, whose position Cantor is understood to covet.

Moreover, Boehner was known to have met privately with the President just before the walk-out; if there were to be anything that could remotely be called a tax increase, a revenue increase, what have you—let Boehner do it. Meanwhile, Cantor would keep his much closer ties with the Tea Party intact. If Boehner stumbled, he’d be ready to take his place.

The politics of the debt ceiling were particularly tricky: Boehner—and the President—knew that perhaps all of the Tea Party members were, “on principle,” unlikely both to vote to raise the debt ceiling and to vote for any measure that had even a suggestion of an increase in revenues. The Speaker would therefore need a large number of Democrats to get a vote through the House. Boehner hadn’t realized at first that he’d have so many Republican defectors—fifty-four—who voted against the continuing resolution he’d negotiated with Obama in early April, on the ground that it didn’t cut spending enough, though Boehner had, in effect, taken Obama to the cleaners. This established in both Democrats’ and Republicans’ minds the thought that Obama was a weak negotiator—a “pushover.” He was more widely seen among Democrats and other close observers as having a strategy of starting near where he thinks the Republicans are—at the fifty-yard line—and then moving closer to their position.

Finding a solution to reducing the deficit that was agreeable to Boehner, to Cantor, to former Speaker Nancy Pelosi, to Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, and to the President was no small task. The men, who had rudely and unwisely excluded Pelosi, now the minority leader, from their deliberations, could no longer avoid dealing with her. They’d considered Pelosi a bit of a pain, insistent as she was on standing up for liberal principles.

Boehner and Cantor, and also Boehner and McConnell, have had their political differences and conflicting political exigencies. Boehner of course wants to retain Republican control of the House—it’s not inconceivable that the Democrats could pick up the necessary twenty-four seats to recover it. Therefore, Boehner didn’t want his flock to have to cast a controversial vote anytime close to the election. On the other hand, with twenty-three Democratic senators up for reelection, McConnell has had his eye on a Republican takeover of the Senate. His party would need to pick up only four seats. Therefore, he was looking for a way to force a controversial vote closer to the election.

In early July, when Obama suddenly injected Medicare, Social Security, and Medicaid into the deficit and debt negotiations, many, perhaps most, Democrats were dismayed. They believed that the President was offering up the poor and the needy as a negotiating gambit. (His position was that if the Republicans would give on taxes, he’d give on entitlements.) A bewildered Pelosi said after that meeting, “He calls this a Grand Bargain?” And she came down firmly against any changes in those programs that would hurt beneficiaries.

Moreover, the Democrats had their own political reasons for opposing reductions in Medicare benefits. They had had great success in campaigning against Paul Ryan’s bizarre proposal, adopted by the House (despite even Boehner’s expressed misgivings), that would turn Medicare into a voucher system. According to Ryan’s plan the government would give future eligible Medicare recipients $6,000 and let them shop for private insurance. (Good luck.)

Having made Ryan’s proposal the centerpiece of the campaign, the Democrats had recently won a special election in a New York district that had been held by the Republicans since the 1950s. The Democrats believed they were onto a good thing.

The question arises, aside from Obama’s chronically allowing the Republicans to define the agenda and even the terminology (the pejorative word “Obamacare” is now even used by news broadcasters), why did he so definitively place himself on the side of the deficit reducers at a time when growth and job creation were by far the country’s most urgent needs?

It all goes back to the “shellacking” Obama took in the 2010 elections. The President’s political advisers studied the numbers and concluded that the voters wanted the government to spend less. This was an arguable interpretation. Nevertheless, the political advisers believed that elections are decided by middle-of-the-road independent voters, and this group became the target for determining the policies of the next two years.

That explains a lot about the course the President has been taking this year. The political team’s reading of these voters was that to them, a dollar spent by government to create a job is a dollar wasted. The only thing that carries weight with such swing voters, they decided—in another arguable proposition—is cutting spending. Moreover, like Democrats—and very unlike Republicans—these voters do not consider “compromise” a dirty word.

The President proposed at least two modest plans for stimulus spending, someone familiar with all these deliberations told me, “but he’s not as Keynesian as before.” This person said, “If the political advisers had told him in 2009 that the median voter didn’t like the stimulus, he’d have told them to get lost.” By 2011, in his State of the Union address in January he moved from jobs creation (such as the stimulus program) toward longer-term investment.

The speech Obama gave on April 13 marked his conversion to fiscal centrism; to being the fiscally responsible Democrat. In that speech he stated that he wanted to reduce the debt by $4 trillion—thus aligning himself with the Republicans—but also asked for revenues to partly offset that reduction. It was all about reelection politics, designed to appeal to this same group of independents. “And that’s why,” I was told by the person familiar with the White House deliberations, “he went bigger in the deficit reduction talks; bringing in Social Security is consistent with that slice of the electorate they’re trying to reach.” This person said, “There’s a bit of bass-ackwardness to this; the deficit spending you’d want to focus on right now is the jobs issue.”

This all fits with another development in the Obama White House. According to another close observer, David Plouffe, the manager of Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign, who officially joined the White House staff in January 2011, has taken over. “Everything is about the reelect,” this observer says—“where the President goes, what he does.”

Plouffe’s advice to the President defines not just Obama’s policies but also his behavior. Plouffe tells the President, according to this observer, that the target group wants him to seem the most reasonable man in the room. Plouffe is the conceptualizer, and Bill Daley, the chief of staff who shares Plouffe’s political outlook, makes things happen; Gene Sperling, the director of economic policy, and Tom Donilon, the national security adviser, are smart men but they come out of politics rather than academia or deep experience in their respective fields. Once Austan Goolsbee, chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, departs later this summer, all of the President’s original economic advisers will be gone. Partly this is because the President’s emphasis on budget cutting didn’t leave them very much to do. One White House émigré told me, “It’s not a place that welcomes ideas.”

Because of the extent to which the President had allowed the Republicans to set the terms of the debate, the attitude of numerous congressional Democrats toward him became increasingly sour, even disrespectful. After Obama introduced popular entitlement programs into the budget fight, a Democratic senator described the attitude of a number of his colleagues as:

Resigned disgust at the White House: there they go again. “Mr. Halfway” keeps getting maneuvered around as Republicans move the goalposts on him.

According to a report in The Hill newspaper in late June, the tough-minded, experienced, and blunt Democratic Representative Henry Waxman of California told Obama in a White House meeting that he’d asked several Republicans about their meeting with him the day before, and, “To a person, they said the President’s going to cave.” Then the congressman said to the President of the United States, “And if you’re going to cave, tell us right now.” The President was reported to have been displeased, and responded, “I’m the President of the United States; my words carry weight.”

Much discussion went on about whether the result of the negotiations would be a “big” deal, reducing the debt by $4 trillion, with $1 trillion coming from revenues and some sort of savings from entitlement programs, as the President and Boehner had privately discussed—although Boehner’s dream of a bipartisan deal was dashed by Cantor on behalf of numerous other House Republicans—or a “small” deal, cutting the debt by about $2 trillion. It was easy to lose sight of the fact that the President was using a lot of his time and energy (he looked very tired) on the wrong subject. And that was even before the arduous, almost daily meetings with the two parties’ leaders.

With the negotiations stalled and time running out, McConnell, worried that the President had manuevered his party into a position where if there were a default the Republicans would be blamed, introduced his own proposal to break the impasse. The very shrewd McConnell warned his Senate colleagues that if they did not take this way out of the impasse, the party’s “brand would be badly damaged.” McConnell’s proposal handed over to the President the authority to raise the debt ceiling, which his own party had been trying so hard to exploit and never dreamed it would surrender to the President.

Under McConnell’s plan, the President would raise the debt ceiling three times for a total of $2.4 trillion before the November election. Each time, Congress would vote on a resolution of disapproval. The proposals Obama could offer would consist of spending cuts only, in keeping with the Republicans’ position that there would be no savings from the tax code. Thus McConnell had maneuvered the Democrats into having to cast three votes on the debt limit. He said that a major goal of his plan was to “reassure the markets that default is not an option.”

McConnell persuaded Harry Reid, the Democratic Senate leader, to cosponsor his proposal, incorporating Reid’s idea of setting up a bipartisan commission of members of the House and Senate who would draw up new budget proposals that would then go to both houses and be considered under a special procedure that would allow no filibuster and no amendments.

The new proposal also contained $1.5 trillion in budget cuts that had been agreed to by a bipartisan group of Senators presided over by Vice President Biden. These were the only cuts that the two parties could agree on, guaranteeing that the cuts would be much more painful for the Democrats.

With two weeks remaining before the day of default, McConnell and Reid were negotiating the fine points of their proposal, and Boehner had made a quiet overture for Nancy Pelosi’s support. (Pelosi had told people that she would demand future protection for Medicare and Social Security.) Some House Republicans expressed opposition to the Senate leadership’s plan. At the same time some conservative members were urging that Congress allow a default, saying that they didn’t believe the results would be as dire as the administration was warning. And then, suddenly, on July 19 the so-called Gang of Six, a bipartisan group of senators led by Democrat Kent Conrad, rode into town with a plan about the size of the one Obama and Boehner had been considering.

The plan envisaged cutting $3.7 trillion from the debt, but the details were vague, and it seemed very unlikely that such a complex plan—offered in the form of a four-page outline—with legislation involving several committees, could be drafted and passed by the Senate and the House within two weeks. The group had been holding back its plan at the White House’s request, but became impatient and fearful that Obama would cave again. The President said he liked the new plan though he had to know there was plenty in it for others to object to. It called for, to begin with, both tax revenues and deep cuts in entitlement programs. Substantial tension was growing in Washington, but to some extent it seemed a phony tension. McConnell and Boehner had vowed there would be no default. Now it was up to them and others to work out what to do instead.

The Republicans displayed a recklessness that should have disqualified them from being taken seriously. Any deal that was reached would contain substantial cuts in the coming fiscal year—too soon, as Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke and the head of the Congressional Budget Office Doug Elmendorf have recently warned.

The antitax dogma of the Republican Party is strongly rooted in mythology. The theory that tax cuts create jobs has been discredited by the results of George Bush’s tax policies. The Republicans cling to the myth that “small business” owners are the “job creators,” and so they oppose proposals to eliminate the Bush rate cuts for even those earning over $250,000. But relatively few small business owners earn $250,000—in fact, fewer than 3 percent of the 20 million people who file business income on their personal tax forms (the 1040s) earn that much.

Finally, the antitax position of many conservatives would seem to be illogical, since they also hate deficits: but their real aim is to reduce or eliminate federal programs. They call efforts to redistribute wealth “socialism,” but have no problem redistributing from the poor and middle class to the wealthy through taxes, as set forth in Paul Ryan’s budget plan, which the House approved on April 15. Under the Ryan plan, the taxes of the richest one percent of Americans would be cut in half, while taxes would be raised on most of the middle class. People earning over $1 million would be taxed at a lower effective rate than the middle class.

Consistent with the philosophy of Ryan’s idol Ayn Rand, this scheme would by 2050 eliminate virtually all federal programs other than defense and Social Security, much of which would be privatized, while his voucher program would replace Medicare. The Ryan plan was so radical that even Republican candidates have been distancing themselves from it though the party higher-ups had declared it a “litmus test” for Republicans seeking office.

Still, liberal-leaning budget analysts agree that the budget is on an “unsustainable” path, with debt constantly rising as a share of the Gross Domestic Product. As of now, the debt is close to 70 percent of GDP. James Horney of the highly respected Center on Budget and Policy Priorities says that that’s a workable percentage, but that steps should be taken to stabilize it by the end of this decade. That would require, Horney says, a substantial amount of deficit reduction—no easy task—including increases in revenues.

This does not mean, Horney adds, that we need to balance the budget to reach that goal. If there are needs to be met by borrowing—especially now, to boost economic growth and employment—we should borrow. The borrowing today should go to extend unemployment benefits (scheduled to expire in December), create infrastructure programs that will provide jobs (for which there are a number of ideas floating around), as well as provide more fiscal relief to the states. (In the recent dismal unemployment figures, public employees were particularly hard hit—partly because they were a target of Republican governors.)

But even more significant is the question of how our leaders, in particular the President, ended up with such misguided policies—emphasizing budget- cutting over growth. The Republicans exploited the need to avoid an economic collapse that could result from not raising the debt limit by demanding that programs that Congress had agreed to should now be unagreed to.

The President began the year with the unfortunate slogan “Win the Future”—which emphatically meant growth and investment. He ended up in Republican territory, at least rhetorically accepting the highly flawed conception equating the federal government with a household: he and Goolsbee repeated the sampler-stitched maxim “We must live within our means,” ignoring that at times the government simply must borrow in order to meet the people’s needs, as is the case now, with high unemployment. It’s no time for austerity. Instead, the government is borrowing in order to give tax cuts to the wealthy and pay for at least two wars.

A final deal became exigent for the major players: naturally, Obama didn’t want to preside over a calamity; and just as urgently, the Republican leaders didn’t want to be pinned with the blame for bringing about the calamity—which poll after poll suggested they would be. Thus it was assumed that a deal would be reached not because the Republicans had a sudden surge of responsibility but because they feared the political consequences of not appearing to be responsible.

Anyway, they had lured the President so far onto their territory that any deal would represent a substantial victory for them—the President’s rhetoric notwithstanding. It was all about theater and politics. But Obama—and the country—would still have to live with the consequences of the policy.

Both the President and the House Republicans, the major parties to the negotiations, are running longer-term political risks. The Tea Party, which has dominated the entire eighty-five-member freshman class, or one third of the Republican House caucus, has pulled the House Republican Party so far to the right that it risks coming across to the public as too obdurate, as putting its own ideology and own partisan interests ahead of the nation’s needs. (And given the possible effects of a default by the United States, perhaps other nations as well.) The “old boys”—the “establishment” Republicans, represented by Boehner—were willing to compromise, while Cantor, as majority leader, had to pay attention to the rambunctious Tea Party group. Each was useful to the other.

In the end, the President had made the Republicans look bad, but what did he get for it? He ended up agreeing to new restrictions that will hamstring his policies for as long as he serves in office. His own actions will have led to new laws that forbid him to borrow money for any government policy—unless, at some time, he goes out and campaigns hard for raising taxes in any form. His actions so far shed light on how likely that is.

This country’s economy is beset with a number of new difficulties, among them that recovery from the last recession remains more elusive than was generally expected, while the US is confronting a variety of international economic instabilities, especially the large debts and possible default of several countries in the eurozone, bringing on unpopular austerity measures. Recent experience with what should have been a simple matter of raising the debt ceiling, normally done with no difficulty, is reason for deep unease about our political system’s ability to deal with such challenges.

—July 19, 2011

This Issue

August 18, 2011

Fooled by Science

How Google Dominates Us

-

*

See my “Bush’s Weird Tax Cut,” The New York Review, August 9, 2001. ↩