The empty stage was already quietly exhilarating, a space where it might be almost as much fun to imagine a play as to see one. For its recent six-week, five-play season at the Armory on Park Avenue in Manhattan, the Royal Shakespeare Company set up a portable version of the company’s home base in Stratford: a tight little performance space seating just under a thousand people, the playing area at once ample and intensely intimate, like a circus tent set up in your living room. The thrust stage reached out into the heart of the audience clustered tightly around on three sides, with the upper tiers looming in close proximity, and two diagonal ramps cutting through the crowd from the back of the house. At least some of the problems of distance that any Shakespeare production must cope with—the physical ones—were done away with at the outset.

Even with the play more or less in your lap, is that close enough? Solitary reading has the inestimable advantage of distending duration at will so that any phrase can inhabit ear and mind as long as desired, a small planet in itself. But finally it needs live production—even if that production were nothing more than actors on a bare stage without props or costumes—to restore the urgencies and counterattacking rhythms of real time. The dream would be to experience living language broadcast live from a vanished source, unimpeded by the erosions wrought by time and circumstance.

However chimerical that desire for unmediated contact, the attempt must always be made. A hundred minor forms of trickery aid in that attempt. Actors must make glances and inflections serve for footnotes; directors must, or at least generally think they must, use design, choreography, and music to make visible unimagined subtexts (whether historical or political or folkloric) and keep the audience from going astray in syntactic mazes. But if the text is not an unbroken skein—a continuous telling—the play has been lost among the bric-à-brac.

Here the RSC has the advantage of a training that emphasizes crisply intelligible vocal delivery. This was alluded to by some New York reviewers as a sort of side benefit or incidental pleasure, but it seems foundational for any company devoted to Shakespeare. If the words are not cutting the air, each with the effect of conscious thought, they are quickly lost in the murk of garbled meanings or the drone of verse rhythms on automatic pilot. The three productions I saw—King Lear, Julius Caesar, and The Winter’s Tale—were enough to reaffirm the RSC, under the current artistic directorship of Michael Boyd, as a superior company of actors intent on keeping the texts alive at each point, their skills so evenly diffused across major and minor roles that even the smallest parts carried the major weight that Shakespeare’s narrative art demands.

The effect of the thrust stage was to make the actors—at least from the vantage point of the front rows—unusually imposing presences. Everything here was foreground, somebody’s foreground at least—such a space does not lend itself to carefully composed stage pictures, the perspective being so radically different from different angles that actors must keep moving about to give each side of the house a chance to take in the scene. In these circumstances bodies and voices were more potent theatrical effects than any of the various blinding flares or thunderous reverberations of crashing scenery.

When it came to overarching directorial schemes the results were decidedly mixed. Lucy Bailey’s Julius Caesar was full of ambitious concepts all the way from its opening dumb show, a feral wrestling match between Romulus and Remus (we had been clued in to their identities by a video display), culminating in the former slitting the latter’s throat. What followed involved much blood-spilling, ritual dancing, and digital display, some deployed artfully to multiply supernumeraries into a convincing vision of the Roman masses, some of it just there, wraparound wallpaper for the eye to land on if the speeches got dull.

Bailey’s premise was anything but frivolous: to put the blood back in a play freighted more than any other of Shakespeare’s with an inheritance of classroom bloodlessness, until at worst it can devolve into a comparative study of rhetorical technique capped by obligatory ceremonial death scenes. She sought a Rome of blood and grime, awash in currents of ecstatic shamanism and annihilating aggression, permeated by a sense of real fear.

This worked best when it belonged to the play. The death of Cinna the poet, closing out the first half, was savage and shot through with sadistic humor; more drastically, a blood-soaked Antony playfully tossing a severed head to Octavius at the beginning of the fourth act was an over-the-top punctuation of what his words already made apparent. But over the long haul the aural and visual overload was counterproductive. The incursions of mobs and armies became musical interludes, bursts of choreographic mayhem to liven things up between the Shakespearean episodes. Crucial dramatic scenes played like lulls, as if Brutus and Cassius were ineffectual onlookers at a raging spectacle beyond their control: perhaps that was the point.

Advertisement

Shakespeare’s characters seemed to be competing with another and much louder play, a play centered on the swirling inarticulate social forces that Caesar, Brutus, or Antony only imagine they can direct. Shakespeare’s playscript itself was at risk of being drowned in simulated gore, muffled by surging shouts, moans, and grumbles (not to mention amped-up thunder and the clash of steel on steel), and upstaged by the ongoing video backdrop, which sometimes—as in the spectacle of Rome in flames that persisted all through the aftermath of Caesar’s assassination—created the illusion that a screening of some savory Italian sword and sandal epic of the early Sixties was in progress at the back of the stage, if only the actors wouldn’t keep getting in the way. (I had to wonder if the image of the crumbling bust of Caesar was intended to be seen as an allusion to Saul Bass’s titles for Spartacus.)

The production’s mood favored Mark Antony, the character most in tune with the general bloodletting, played by Darrell D’Silva as an ambitious hell-raiser, brutal, boozily sentimental, and with a cynical flair for the common touch. “Friends, Romans, countrymen” was barked out effectively as a military command, but this characterization left him little to do with the “noblest Roman” encomium after Brutus’ death, delivered with no more force than a bit of pro forma spin control. His grief and rage for Caesar’s death were persuasive, and Greg Hicks’s Caesar (an exactly etched if narrow likeness) was the sort that such an Antony might admire: wiry, energetic, and arrogant, and just enough a creature of vanity and whims to allow him to be manipulated. Sam Troughton—working with a cane following a knee injury earlier in the season—was a depressive and self-contained Brutus, a still center that might harbor a death wish, in contrast to John Mackay’s unusually sympathetic Cassius, played as a neurotic humorist with a far sharper pragmatic sense. Of the rest, Hannah Young’s Portia stood out particularly, more determined patrician’s daughter than submissive wife.

The same day I saw Greg Hicks as Caesar at the matinee, he was due to play King Lear in the evening, an impressive feat in itself. I caught up with his Lear, which some critics had found insufficiently maddened, a week or so later. David Farr’s production, the night I saw it, came across as a swift and vigorous reading that very much brought out the RSC’s ensemble virtues. Here every role, not just Lear’s, was central. What came through most clearly was the insidious beauty of the storytelling, its enlistment of every device of humor and lyric and suspense in the service of unfolding catastrophes. This was not the most shatteringly apocalyptic of Lears, but it was emotionally persuasive and dramatically alive enough to forestall any perplexing over the production design.

Sets and costumes veered between the Middle Ages and the World War I era—helmeted doughboys moved props between scenes, the storm-wracked heath was situated in a bombed-out factory district (while the storm itself was a matter of flickering and crackling overhead lighting fixtures, and a shower of water suggestive of a ruined plumbing system)—and Lear was eventually consigned to the care of a Red Cross nurse, while hymns were intoned in cloisters and Edgar and Edmund fought it out with swords in the manner of Ivanhoe. No particularly pronounced historical or mythic vision seemed to be in operation; not that Lear needs any such embellishment. I cannot think of a drama less in need of additives.

Hicks is a vocally agile actor, pleasing in an arioso way when he wants to be, and capable of very penetrating portraiture, as his Leontes in The Winter’s Tale in particular demonstrated. Too evidently sharp and fit to convincingly portray feebleness either of mind or body, his Lear was more a case of toughness beating against itself, his problem not failing strength but inability to govern the strength he still had. He beat back at the “hysterica passio” of his heart as if overwhelmed by its rebellious force, not its faltering. This was a nastily sarcastic ruler—reeling off his curse on Goneril with the bravura of a long-practiced virtuoso of slanging matches—too arrogant to realize how seriously he has misstepped in dividing his realm, very much a king but too pigheaded ever to have been a very efficient one, in fact the type of a self-satisfied and not terribly intellectual provincial tyrant.

Advertisement

Whatever “better nature” he has is forged out of nothing in the storm; if Hicks’s bursts of rage did not quite attain the highest pitch of madness, the manic glee that followed was beautifully inhabited, giving the encounter with the blinded Gloucester a quality of demented pastoral right on the edge of the frankly comic. Lear does not return to his old self—there was so little to return to—but by bizarre miracle uncovers fragments of a new and still half-formed self, an awakening that collapses in the wake of Cordelia’s death.

The embers of sexuality still clung about this Lear, suggested in part by the three strong performances of the daughters. Kelly Hunter’s terminally needy Goneril gave enough signs of emotional damage to elicit something like sympathy for at least part of the way, her wrenching sobs at Lear’s curse suggesting that this was hardly the first time she had suffered such abuse from her father. Regan, sometimes played as Goneril’s knowing coconspirator, here was caught up in her own private world of role-playing sexuality, a theatrical universe with a cast of one. Both, one could feel, were truly Lear’s daughters, the pure products of his tutelage and example, while Cordelia stood out abrasively as the disaffected rebel in the family. Samantha Young’s Cordelia was hard-nosed and skeptical enough to raise the question of how much she really did love her father as more than a stoically accepted obligation: more than Goneril or Regan, to be sure, but that would hardly be saying much.

Geoffrey Freshwater as Gloucester and Charles Aitken as Edgar were exceptionally good, both characters continuing to evolve in complicated ways from scene to scene, and the hard-to-play (because always a little hard to believe) episode in which Edgar pretends to lead his father to his death on the cliffs of Dover was for once both moving and plausible: a ritual enacted between a father and son unable to communicate other than by circuitous symbolic means.

Tunji Kasim’s Edmund was rooted in an intriguing notion that didn’t fully blossom. This was no deep-dyed Machiavellian but a cocky kid just embarking on an ocean of evil, inwardly exhilarated but keeping his cool, and half-amazed at his own daring. Set against Clarence Smith’s brisk and heartless Cornwall, the very model of an effective warlord, Edmund looked like a wannabe who might not last all that long among the real gangsters. Kasim projected the slippery charm of a budding con man, but at moments there was a sense that he was letting himself off the hook a bit too easily, perhaps with a view toward making Edmund’s halfhearted dying turnaround more plausible than usual.

Sophie Russell’s Fool was a crucial presence, something like a voice of sweet reason, the intellect that Lear lost or discarded or perhaps never had, and loved by him as no one else quite is—not even Cordelia, since Cordelia is family and family with Lear is painful wherever it crops up. The Fool by contrast is an unfettered companion, emblem of an imaginary freedom. The shock that Russell registered at the eruption of folly on all sides was in its quiet way close to being the emotional center of the production.

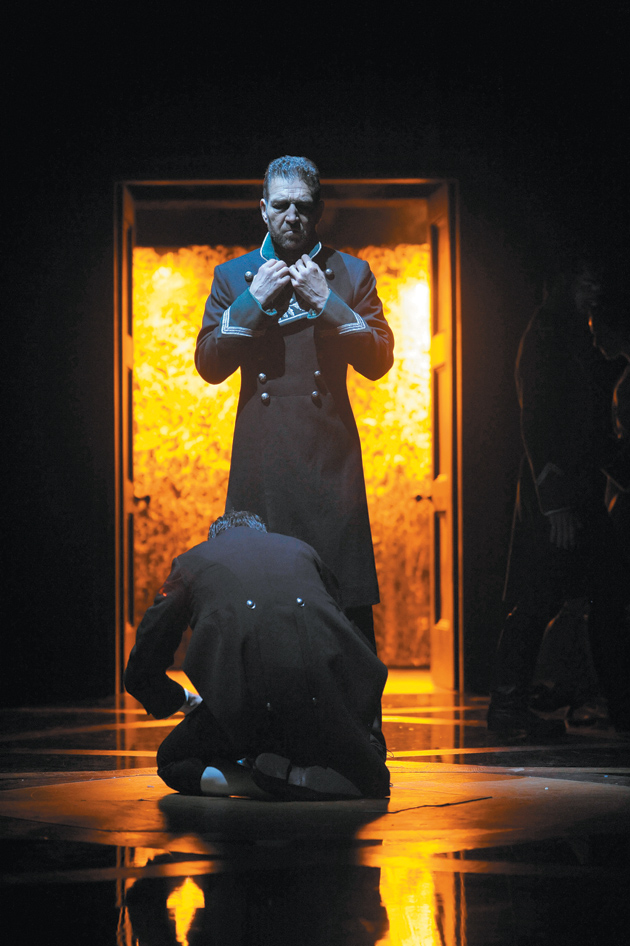

Of the productions I saw, The Winter’s Tale was the most satisfying, not least for Greg Hicks’s Leontes, a remarkably precise enactment of power gone sick, turned inward against itself and thus by extension against everyone else. The difficulties of the part are there from the outset. His fit of mad jealousy comes upon him at the start of the long opening banquet scene in which he and his queen, Hermione, entertain his long-lost childhood friend Polixenes of Bohemia, who is preparing to return home. When Hermione follows her husband’s bidding and cajoles his friend to stay on, Leontes conceives the thought that Polixenes may be Hermione’s lover, and jealousy descends on him and utterly possesses him within seconds—or rather we hear it descend, in the corkscrewing turns of some of the most arduous soliloquies in Shakespeare. Ezra Pound once summed up his understanding of Confucian philosophy in a single phrase: “Avoid twisty thoughts.” Leontes is a man with thoughts so twisty that they have looped around him and drawn him into himself without hope of extrication, so that Shakespeare must invent a new grammar to catch their whiplash bends and sudden cavernous gaps.

He is a negative force field, the embodiment of an infected mind, so taken over by his thoughts that they rule him, and through him reach out to destroy everyone in sight—his wife, his son (however unintentionally), his newborn daughter—and beyond that all the traitors and fools who get in the way of those thoughts, which by the end of act three is pretty much everyone at the court of Sicilia. The court was here a book-lined nineteenth-century suite—it might have been an interior for an Ibsen or Strindberg play—a space already hermetic. Within that space, lighting was used to isolate Leontes from the rest of the banqueters, but it was Hicks who made that isolation absolute with every inflection of his playing.

From his first entrance he radiated an impacted discomfort just barely able to conceal itself, shrinking from the sloppy embrace of his old comrade Polixenes as if wanting to disappear altogether, an inward recoiling made visible, corresponding to the snakelike coilings of his thoughts. As played by Darrell D’Silva, Polixenes was a bluff country squire, generous and choleric in equal measure, and verging at moments on fatuity. His openness and lack of cant would help explain the dynamic of his childhood friendship with an intellectually sharp and emotionally convoluted Leontes very much his complementary opposite.

The director David Farr came close to implying, through choreographed body language, that there might be a real basis for Leontes’s jealousy, leading to some distracting byplay between the suspected couple in the finale, with Polixenes conveying mimed regrets amid the general reconciliation. The point should have been clearer. However plausible an attraction between the two—certainly Hermione would be apt to find Polixenes a welcome relief from the relentlessly inner-directed Leontes—it is surely crucial to the play that she be understood to be innocent of her husband’s accusations.

The psychological warfare of Leontes against himself and all around him is, after all, an intellectual malady, a failure of the capacity to interpret the world. Haggard with sleeplessness—“Nor night nor day no rest”—Greg Hicks reached out for a book from the bookcase, staring at its pages blankly as if hoping that someone else’s words might relieve him from his own galloping thoughts. This was a despair conscious of itself, observing its progress with fascination, yet powerless to intervene: beyond smiles except the most transparently faked, beyond caresses or affectionate handshakes, wiping his wife’s kiss off his brow as if it would poison him, shipwrecked on the barren shores of mind.

Throughout the first three acts (perhaps the most breathlessly sustained piece of exposition in Shakespeare) there is not even a momentary relaxation of the tension that consists of nothing more than Leontes himself. He is the catastrophe against which everyone else must struggle, and be transformed in the process. Noma Dumezweni was harshly eloquent as Hermione’s confidante Paulina, the heart and soul of opposition to Leontes’s madness; and Kelly Hunter matched her powerful Goneril with a Hermione who registered with convulsive force the rapid transition from expansive self-confidence to sudden bewilderment following the horrified realization that her world has been destroyed.

Hermione’s indignation in the trial scene—in which she is accused of being pregnant with Polixenes’s child—came to a peak with the line: “You speak a language that I understand not.” Here it felt like the central line of the play, since Leontes has long since lost the use of language as a means for communicating between people. The complicated swirls of thought with which the play begins now give way to a language of compressed force, as when Leontes cries: “Your actions are my dreams!”

Hicks realized that the line was the articulation of Leontes’s essential confusion of inward and outward, a confusion that has driven the play through Hermione’s trial and imprisonment and that will impel it forward right up to the announcement of the exculpatory oracle followed immediately by news of his son’s death: the instant in which, like a pricked balloon, the play we have been watching collapses to make way for another play. Hermione herself dies, having collapsed in grief. What has departed forever is the Leontes who dominates those acts so thoroughly. He has run himself into ultimate exhaustion, leaving little more than a remnant of a character, hardly capable of the slightest effort of will until the moment—much later on—when he will come to aid of his daughter Perdita and her lover Florizel, Polixenes’s only son.

There is, of course, the other play, the pastoral comedy of act four, and yet another play beyond that, the long restoration episode of the final act. The play was divided here by the dramatic collapse of the first part’s bookshelves, whose wreckage becomes at first the desolate seacoast of Bohemia and then with only slight adjustment the rustic province where Perdita has blossomed into maidenhood. The symbolic significance of the palace’s neatly ranged books becoming, as torn and scattered pages and bindings, the rural world of Perdita’s upbringing somewhat escaped me, unless the leaves of the torn books were meant as a metaphor for the leaves of the Bohemian summer.

It was an elegant idea to restrict things to two sets that were essentially one set in two different states—rigidly cohesive and exuberantly scattered—so as to underscore the grand binary division of the play with its suggestion of so many other oppositions: winter and summer, tragedy and comedy, age and youth, royalty and peasantry, sickness and health. The play’s two halves are dominated respectively by Leontes and Autolycus, the sad king and the merry thief and vagabond who helps Perdita and Florizel escape. A ruler by misruling himself brings everything into ruin; a lord of misrule, very much despite himself, becomes the instrument for making all well again. Leontes, however much he may have merited eternal suffering, is finally readmitted to the circle of human warmth; Autolycus, in a nice touch, was here the only one left out in the cold, ruefully accepting his lot as the snow of another winter fell on him.

Where the first half was fine-tuned in its tensions, the second was permitted to collapse into a shaggier affair, with the satyrs’ dance of the “hairy men” (clad here in the tattered leaves of books and brandishing priapic appendages that would likely be the stuff of Leontes’s nightmares) positioned as high point rather than interlude. The stage was at times so cluttered that Perdita and Florizel got somewhat lost in the shuffle; one wanted them a bit more in the center of things from time to time. Brian Doherty brought energetic authority to his Autolycus and there was real hilarity in the scene in which, dressed in Florizel’s abandoned robes, he poses as a courtier to gull an Old Shepherd and his son out of their gold, while accidentally laying the groundwork for the revelation of Perdita’s royal parentage. In The Winter’s Tale the mechanisms of farce and the mechanisms of magical restoration are intricately intertwined.

Samantha Young’s Perdita was more rough-hewn than princess-like in her demeanor, very much the hardheaded peasant. What Young nicely caught was a young woman just grasping her own superiority of intellect and clarity of vision compared to those around her, yet still spontaneous enough to acknowledge faults and shortcomings without fear of losing advantage. Her resounding performance, with those of Noma Dumezweni and Kelly Hunter, brought home how much this is a woman’s play, to the extent that Shakespeare ever wrote one.

The kings fail, each in turn giving way to jealousy and anger (first as tragedy, then as comedy) and thereby losing their sense of what is real. The victims, Hermione and Perdita, must be restored to place and power; and Paulina, the voice of fearless protest, will become the beneficent wonder-worker bringing about the last act’s restoration miracle. The miracle is that of theater, bringing the dead to life despite every law of probability, until Leontes refuses to let Paulina bring the curtain down on the statue of his queen (who soon comes to life), preferring the “madness” of that impossible spectacle to the all too sane acceptance of hopeless loss that “settled senses” yield: “No settled senses of the world can match/The pleasure of that madness. Let’t alone.”

This Issue

September 29, 2011

School ‘Reform’: A Failing Grade

Coming Attractions

After September 11: The Failure