Ernest Hemingway, the second oldest of six children, was born in Oak Park, Illinois, in 1899 and lived until 1961, thus representing the first half of the twentieth century. He more than represented it, he embodied it. He was a national and international hero, and his life was mythic. Though none of his novels is set in his own country—they take place in France, Spain, Italy, or in the sea between Cuba and Key West—he is a quintessentially American writer and a fiercely moral one. His father, Clarence Hemingway, was a highly principled doctor, and his mother Grace was equally high-minded. They were religious, strict—they even forbade dancing.

From his father, who loved the natural world, Hemingway learned in childhood to fish and shoot, and a love of these things shaped his life along with a third thing, writing. Almost from the first there is his distinct voice. In his journal of a camping trip he took with a friend when he was sixteen years old, he wrote of trout fishing, “Great fun fighting them in the dark in the deep swift river.” His style was later said to have been influenced by Sherwood Anderson, Gertrude Stein, Ezra Pound, journalism, and the forced economy of transatlantic cables, but he had his own poetic gift and also the intense desire to give to the reader the full and true feeling of what happened, to make the reader feel it had happened to him. He pared things down. He left out all that could be readily understood or taken for granted and the rest he delivered with savage exactness. There is a nervy tension in his writing. The words seem to stand almost in defiance of one another. The powerful early stories that were made of simple declaratives seemed somehow to break through into a new language, a genuine American language that had so far been undiscovered, and with it was a distinct view of the world.

He wrote almost always about himself, in the beginning with some detachment and a touch of modesty, as Nick Adams in the Michigan stories with his boyish young sister in love with him, as Jake Barnes with Lady Brett in love with him, as the wounded Frederic Henry with Catherine Barkley in love with him, Maria in For Whom the Bell Tolls, Renata in Across the River and Into the Trees. In addition to love, he dealt in death and the stoicism that was necessary in this life. He was a romantic but in no way soft. In the story “Indian Camp” where they have rowed across the bay and are in an Indian shanty near the road:

Nick’s father ordered some water to be put on the stove, and while it was heating he spoke to Nick.

“This lady is going to have a baby, Nick,” he said.

“I know,” said Nick.

“You don’t know,” said his father. “Listen to me. What she is going through is called being in labor. The baby wants to be born and she wants it to be born. All her muscles are trying to get the baby born. That is what is happening when she screams.”

“I see,” Nick said.

Just then the woman cried out.

“Oh, Daddy, can’t you give her something to make her stop screaming?” asked Nick.

“No. I don’t have any anaesthetic,” his father said. “But her screams are not important. I don’t hear them because they are not important.”

The husband in the upper bunk rolled over against the wall.

The birth, the agony, the Caesarean, and the aftermath are all brilliantly described in brief dialogue and a few simple phrases. But every word, every inversion or omission is important. Of such stuff were the first stories made. “My Old Man” was chosen for Edward O’Brien’s Best Short Stories of 1923. “Up in Michigan,” another story, was—for its time—so frank and disturbing that Gertrude Stein called it unpublishable.

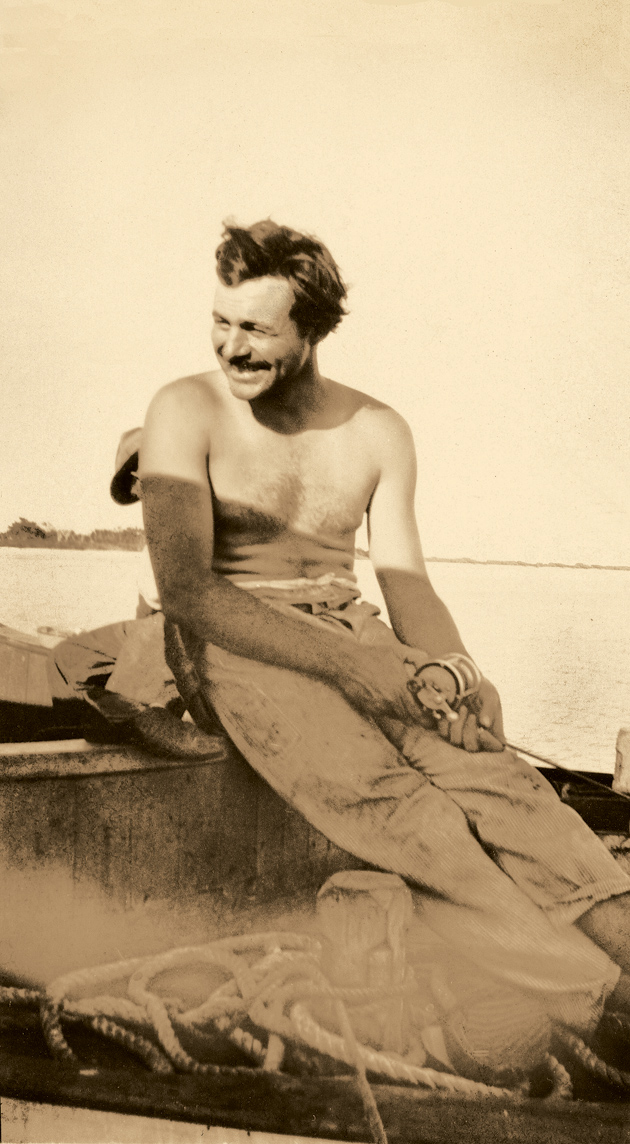

Hemingway was a handsome and popular figure in Paris in the early 1920s; there is the image of him walking down the Boulevard Montparnasse in his confident athletic way past cafés where friends call out or gesture for him to join them. He was married to Hadley, his first wife, and they had an infant son, Bumby. He was writing in notebooks, in pencil, lines of exceptional, painstaking firmness. His real reputation commenced in 1926 with The Sun Also Rises, swiftly written in eight weeks, based on his experiences going to Pamplona and his fascination with bullfighting. The characters were based on real people. Brett Ashley, in life, was Lady Duff Twysden:

Brett was damned good-looking. She wore a slipover jersey sweater and a tweed skirt, and her hair was brushed back like a boy’s. She started all that. She was built with curves like the hull of a racing yacht, and you missed none of it with that wool jersey.

It’s written with exuberance—“racing yacht” with its connotation of fast, sporting, gallant, its aura of heedless days. Words of one syllable that hit you all at once. Lady Duff Twysden liked being written about. Harold Loeb, who was Robert Cohen in the book, didn’t. He was portrayed as a Jew who wanted to belong to the crowd and never really understood that he couldn’t. The portrait bothered Loeb all his life. He had been a friend of Hemingway’s. He felt betrayed. Hemingway was generous with affection and money, but he had a mean streak. “I’m tearing those bastards apart,” he told Kitty Cannell. He was fine if he liked you but murder if he didn’t. Michael Arlen was “some little Armenian sucker after London names”; Archibald MacLeish, once his close friend and champion, was a nose-picking poet and a coward. As for Scott Fitzgerald, who was a couple of years older, successful before Hemingway, and had recommended him to Scribner’s, Hemingway said he wrote “Christmas tree novels,” was “a rummy and a liar and dishonest about money.”

Advertisement

Hemingway broke with almost all his literary friends—MacLeish, Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein, John Dos Passos, Ford Madox Ford, and Sherwood Anderson—although he remained loyal to Ezra Pound and never had the chance to break with James Joyce. Almost all of his likes and dislikes, appraisals, opinions, and advice are in his letters. It is estimated that he wrote six or seven thousand in his lifetime to a great variety of people, long letters bursting with description, affection, bitterness, complaint, and great self-regard: it’s hard not to admire the man, whatever his faults, who so boldly wrote them.*

In 1929 came A Farewell to Arms, which marked Hemingway’s complete ascension. Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby had been published four years before but had somewhat disappointing sales. Hemingway’s novel burst like a rocket. It had been serialized in Scribner’s magazine and the first printing of 31,000 copies was quickly doubled.

In the 1930s Hemingway wrote two books of nonfiction: Death in the Afternoon, explaining and glorifying bullfighting, and Green Hills of Africa, based on a long-anticipated hunting trip to British East Africa in 1933–1934. They are books in which Hemingway as the writer is very present and delivers various opinions and feelings. The books were not particularly well received. The critics, who once praised him and whom Hemingway now detested—lice, eunuchs, swine, and shits, he called them—were scornful. Green Hills of Africa had been a small book for a big man to write, one of them said. Edmund Wilson, initially Hemingway’s champion, astutely wrote:

For reasons which I cannot attempt to explain, something frightful seems to happen to Hemingway as soon as he begins to write in the first person. In his fiction, the conflicting elements of his personality, the emotional situations which obsess him, are externalized and objectified; and the result is an art which is severe, intense and deeply serious. But as soon as he talks in his own person, he seems to lose all his capacity for self-criticism and is likely to become fatuous or maudlin…. In his own character of Ernest Hemingway, the Old Master of Key West, he has a way of sounding silly. Perhaps he is beginning to be imposed on by the American publicity legend which has been created about him.

This was written in 1935.

They were beginning to pic him, to get him to lower his head. The letters of outrage he wrote were childish and violent. He believed in himself and his art. When he began it was fresh and startling. Over time the writing became heavier, almost a parody of itself, but while living in Key West in the 1930s he wrote two of his finest stories, “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” and “The Snows of Kilimanjaro.” And in 1940 his big novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls, based on his experiences as a correspondent in the Spanish civil war, redeemed his reputation and restored him to eminence.

Paul Hendrickson’s rich and enthralling Hemingway’s Boat, which covers the last twenty-seven years of Hemingway’s life, from 1934 to 1961, is not, as is made clear at the beginning, a conventional biography. It is factual but at the same time intensely personal, driven by great admiration but also filled with sentiment, speculation, and what might be called human interest. Hendrickson can write an appreciation of a photograph of Hemingway, his wife Pauline, and a boat hand named Samuelson sitting at a café table in Havana as if it were an altarpiece, and can give Havana itself—its bars, cafés, the Ambos Mundos Hotel, the ease of its life and dedication to its vices—a bygone radiance, a vanished city before its puritan cleansing by Castro.

Advertisement

On returning to America from his African safari in 1934, Hemingway fulfilled a long-held desire to buy a sea-going fishing boat, and at a boatyard in Brooklyn he ordered the thirty-eight-foot cabin cruiser that he christened Pilar, his favorite Spanish name and also the secret name for his second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer, from early in their romance. In May 1934 his boat was delivered.

In Hendrickson’s book there is a great deal about this boat, by whom it was built, what it cost, its many particulars, all supporting the central part it played in the next two decades of Hemingway’s life. He needed physical activity as a relief from the intense effort that went into his writing, and he had always loved fishing. This was fishing for marlin, the great blue marlin, gigantic fish, four or five, even six hundred pounds, “their girth massive,” “their bills like swords.” When hooked they would literally walk on water. They appeared every summer off Bimini and then came down along the Cuban coast, traveling in the Gulf Stream, the great sea-river, deep blue to black, six or more miles wide. The battles with them, sometimes hours long, were savage, almost prehistoric, with the heart-stopping thrill of the strike and line screaming from the big reel. “Yi! Yi! A marlin!” Hemingway cries to his wife, “He’s after you, Mummy! He’ll take it!”

The deep, primal fears, the great fish fighting ferociously against the steel hook in its mouth, hour after hour, sounding, bursting from the water, struggling to be free and being slowly exhausted, the fisherman pumping and reeling in until the fish is gaffed alongside or even in the boat. In his first two years Hemingway caught ninety-one of them. One had jumped three times toward the boat and then thirty-three times against the current. That fish or another, gotten on board alive, had jumped twenty times or more in the cockpit.

In articles for Esquire, Hemingway wrote of all this with tremendous power. He was a heavyweight. Broad-shouldered, mustached, with an outlaw’s white smile, he dominated the marlin. He broke them. In Bimini once he returned to the dock

close to midnight in a jubilant drunk to find his 514-pound giant bluefin tuna that he’d fought for seven hours…and pound[ed] his fists over and over into the strung-up raw meat in moonlight the way prize-fighters in the gym slam at the heavy bag.

He had boxed almost all his life—Morley Callaghan, Mike Strater, and Harold Loeb in Paris. He even taught Ezra Pound to box. In Bimini he’d issued an island-wide challenge, a hundred dollars to anyone who could go three rounds with him. No one, it’s said, managed to.

He enjoyed taking people out on the Pilar to fish or to show them the excitement of it, Dos Passos and MacLeish before he broke with them, and Arnold Gingrich, who was the editor of Esquire and who married a sporty blond woman, Jane Mason, who’d been Hemingway’s mistress and was the model for Mrs. Macomber. The boat was used as well for cruising along the Cuban coast—the island is eight hundred miles long—to secluded bays where they would have lunch, swim, siesta, and sometimes stay for a few days.

Paul Hendrickson, who won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Sons of Mississippi—a book about the white sheriffs who, in 1962, tried to stop James Meredith from enrolling at the University of Mississippi—is a deeply informed and inspired guide. He often appears in the first person, addressing the reader and exhorting him or her to speculate, imagine, or feel. He has researched exhaustively, been to the places Hemingway frequented, and talked to whoever was part of or had a connection to the Hemingway days. He interviewed all three of Hemingway’s sons in 1987 for a piece about them in The Washington Post. His diligence and spirit are remarkable. It is like traveling with an irrepressible talker who may go off on tangents but never loses the power to amaze. The book not only traces the history of the boat with all its associations but also the longer arc of Hemingway’s life—his childhood, youth, companions, manhood, and achievement—in its full rise, fall, and finally rise again. Not a bell, as Hendrickson writes, but a sine curve.

There exists a general feeling that Hemingway was better earlier; his books were better, he was better as a man. By the time he was fifty, his son Gregory—with whom he had a difficult relationship—said he was “a snob and a phony.” The hotels, the Ambos Mundos and the Compleat Angler, seemed to become the Gritti Palace, Ritz, and Sherry-Netherland, and there was much association with rich or fashionable people. He had worked hard all his life. He had been to three wars, he had always showed up. “When you have loved three things all your life,” he wrote, “from the earliest you can remember; to fish, to shoot and, later, to read; and when all your life the necessity to write has been your master, you learn to remember.” And in a famous letter to his former wife, now Hadley Mowrer, he wrote:

Now I’ve written good enough books so that I don’t have to worry about that I would be happy to fish and shoot and let somebody else lug the ball for a while. We carried it plenty and if you don’t know how to enjoy life, if it should be the only one life we have, you are a disgrace and don’t deserve to have it. I happen to have worked hard all my life and made a fortune at a time when whatever you make is confiscated by the govt. That’s bad luck. But the good luck is to have had all the wonderful things and times we had. Imagine if we had been born at a time when we could never have had Paris when we were young. Do you remember the races out at Enghien and the first time we went to Pamplona by ourselves and that wonderful boat the Leopoldina and Cortina d’Ampezzo and the Black Forest?… Good bye Miss Katherine Kat. I love you very much.

It is Hemingway at his most gentle, elegiac, and self-pitying. Eight years after writing it he published Across the River and Into the Trees, an autobiographic novel about an aging colonel wildly in love with a young Italian woman in Venice that took his egotism to new heights and was ridiculed mercilessly, made worse by the notorious interview he gave to Lillian Ross that provided an equally devastating portrait. But he followed this with one of his most popular and enduring works, The Old Man and the Sea, about an epic marlin and an aged fisherman’s courage, written in Hemingway’s heroic style, uplifting, open to being mocked.

In 1954 he was given the Nobel Prize. Gabriel García Márquez, still a journalist, caught sight of Hemingway and his wife in Paris one day in 1957 walking along the Boulevard Saint-Michel. Hemingway was wearing old jeans and a lumberjack’s shirt. He had long been one of García Márquez’s great heroes, for his myth as well as his writing. The Old Man and the Sea had hit García Márquez “like a stick of dynamite”; he was too timid to approach Hemingway but also too excited not to do something. From the opposite side of the street he called out, “Maestro!” Hemingway raised a hand as he called back “in a slightly puerile voice,” “Adios, amigo!”

His health was deteriorating. There was recurring depression as well as the effects of serious injuries from two successive airplane crashes in Africa in 1954 that resulted in concussion, a fractured skull, a ruptured liver, and a dislocated arm and shoulder. Over the years he’d had many diseases, broken bones, and a number of wounds. There were also diabetes, hypertension, migraine headaches, and the cumulative cost of decades of hard drinking. He had night terrors and thoughts of suicide. His father had committed suicide—shot himself—in 1928. Writing was becoming increasingly difficult, and he had always put into it everything he had. His style became in some respects a kind of imitation of itself, a close imitation although, as Walter Benjamin noted, only the original of anything has authentic power.

Still, toward the end, in 1958, he finished the beautiful remembrance of his youth in Paris, A Moveable Feast, written with a simplicity and modesty that seemed long past. As with much of Hemingway, it fills one with envy and an enlarged sense of life. His Paris is a city you long to have known. Two of his novels never put in final form by him have been published posthumously, The Garden of Eden and Islands in the Stream. Like all his books, they sold well. In 2010 Scribner’s sold more than 350,000 copies of Hemingway’s works in North America alone. By far the most popular is The Old Man and the Sea.

There are lengthy though discerning portraits of minor characters in Hendrickson’s book. They are of interest mainly because they are neglected witnesses. The longer one, affectionately done, is of Walter Houk, who served in the US embassy in Havana at the end of the 1940s and whose girlfriend Nita worked for Hemingway as his secretary. She introduced Houk to Hemingway and they became friends. The Houks were married at Finca Vigía, Hemingway’s house; he gave the bride away. Houk’s memories are firsthand, meals with the Hemingways, swims in their pool, voyages on the Pilar. A kind of rosy nostalgia seems to be taking over when suddenly, in the final riveting act, there enters a grotesque, almost demonic figure, tortured, mesmerizing, a doctor with the prodigious wreckage of three wives, seven or eight children, alcohol, drugs, and adultery trailing behind him, a transvestite who finally has a sex change operation and ends up dying in jail: the always troubled, gifted youngest son, Gregory Hemingway.

He is last seen sitting on the curb in Key Biscayne one morning after having been arrested the night before trying to get through a security gate. He’s in a hospital gown but otherwise naked with some clothes and black high heels bunched in one hand. He had streaked, almost whitish hair that morning, painted toenails, and as the police approached was trying to put on a flowered thong. Five days later he died of a heart attack while being held in a Women’s Detention Center. He was listed as Gloria Hemingway. This was in 2001; he was sixty-nine years old.

The last, very moving section of Hemingway’s Boat is devoted to Gregory, Gigi as he was always called, rhyming with “biggy,” the wayward son who as a boy was caught trying on his stepmother’s white stockings. “He was a boy born to be quite wicked who was being very good…,” Hemingway wrote in his fictional version, Islands in the Stream. “But he was a bad boy and the others knew it and he knew it.” Hendrickson says, “I’ll whoof this straight out: a lifelong shamed son was only acting out what a father felt….” And these were possibly the transsexual fantasies in The Garden of Eden along with all the women in Hemingway with hair cut short like a boy’s.

When Gigi’s oldest child, Lorian, saw him for the first time in years, he took her out in a chartered boat to show her big-game fishing, but then embarrassingly lost the big marlin he’d hooked. He hadn’t slacked, and the line had snapped. He’d made a botch of it. He seemed broken. She reached out and touched his forhead in sympathy. “Sorry, Greg,” she said. “You’re a pretty girl,” he said. “A very pretty girl. Call me ‘Father,’ would you?” She noticed the nail polish on two of his cracked and dirty nails.

Hemingway’s declining health and psychological problems were more serious at the end of the 1950s. He had shock treatments at the Mayo Clinic and believed the FBI was following him. (In fact FBI agents had compiled a large file on him.) He was delusional and slurring his speech. It was kept from the public. He was unable to write as much as a single sentence. In chilling detail Hendrickson gives the almost step-by-step account of his final hour when he rose early one morning in Ketchum, Idaho, put on his slippers, and went quietly past the master bedroom where his wife was sleeping. The suicide could be seen as an act of weakness, even moral weakness, a sudden revelation of it in a man whose image was of boldness and courage, but Hendrickson’s book is testimony that it was not a failure of courage but a last display of it.

Hemingway’s Boat is a book written with the virtuosity of a novelist, hagiographic in the right way, sympathetic, assiduous, and imaginative. It does not rival the biographies but rather stands brilliantly beside them—the sea, Key West, Cuba, all the places, the life he had and gloried in. His commanding personality comes to life again in these pages, his great charm and warmth as well as his egotism and aggression.

“Forgive him anything,” as George Seldes’s wife said in the early days, “he writes like an angel.”

This Issue

October 13, 2011

After September 11: Our State of Exception

Does the Euro Have a Future?

-

*

A new edition of the letters is now in progress. See The Letters of Ernest Hemingway: Volume 1, 1907–1922, edited by Sandra Spanier and Robert W. Trogdon (Cambridge University Press, 2011). ↩