A Roberto Bolaño piece of some four and a half pages collected in The Return begins, “Once, after a conversation with a friend about the mercurial nature of art, Amalfitano told a story he’d heard in Barcelona.” This was written in 1997, six years before Bolaño died in 2003. Like a number of Bolaño’s characters, Amalfitano appears in more than one of the Chilean writer’s fictions; readers of 2666, his last major novel, published in English in 2009, will know him as the melancholy professor of literature in Santa Teresa (based on Ciudad Juarez) in northern Mexico, where, in a Duchampian gesture that is hard to interpret, he hangs a geometry book on the washing line in his backyard.

The story he heard in Barcelona concerns a little Sevillean known as the rookie (el sorche), who winds up fighting for the Germans against the Russians in World War II. Having received a minor wound the rookie is hospitalized, but on his discharge gets sent, by administrative error, to the barracks of an SS battalion, where he is set to work as a cleaner. In due course the Russians overrun the barracks, and the rookie, who speaks no Russian and only four words of German, is tortured for information. The Russians strap him into an SS interrogation chair and apply pincers to his tongue:

The pain made his eyes water, and he said, or rather shouted, the word coño, cunt. The pincers in his mouth distorted the expletive which came out, in his howling voice, as Kunst.

The Russian who knew German looked at him in puzzlement. The Andalusian was yelling Kunst, Kunst and crying with pain. In German, the word Kunst means art, and that was what the bilingual soldier was hearing, and he said, This son of a bitch must be an artist or something. The guys who were torturing the Andalusian removed the pincers along with a little piece of tongue and waited, momentarily hypnotized by the revelation. The word art. Art, which soothes the savage beast. And so, like soothed beasts, the Russians took a breather and waited for some kind of signal while the rookie bled from the mouth and swallowed his blood liberally mixed with saliva, and choked. The word coño transformed into the word Kunst, had saved his life. When he came out of the rectangular building, it was dusk, but the light stabbed at his eyes like midday sun.

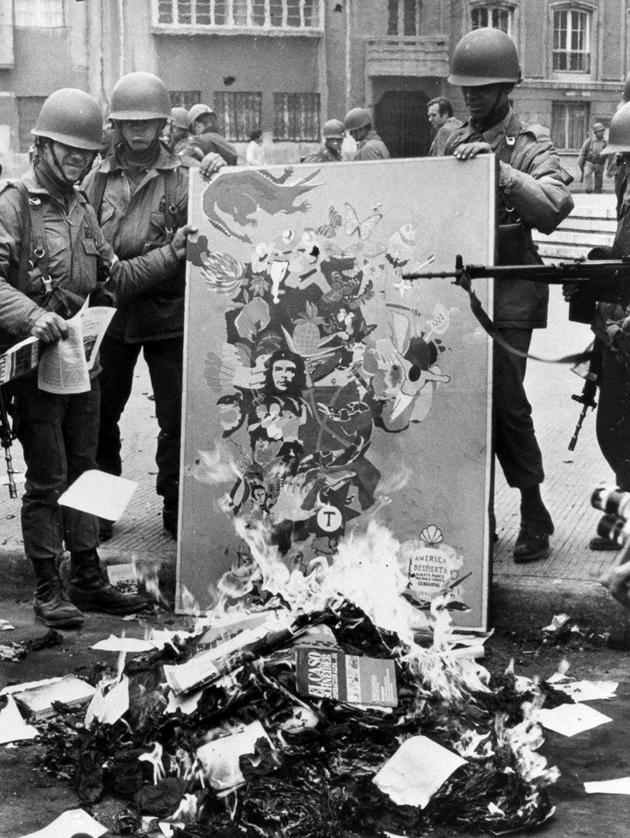

Since the pronouncements of such writers as Theodor Adorno and Walter Benjamin (“There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism”), making links between art and violence has become as routine and clichéd as a parlor game. There is nothing routine or clichéd, however, or at all theoretical, in Bolaño’s treatment of what has become a truism. The narrator of By Night in Chile, a Catholic priest on his deathbed who was once summoned to teach Pinochet about Marxism, recalls how he would attend parties in Santiago at the house of a not untalented novelist called María Canales, who was at the time married to an American who everyone assumed was a corporate salesman or executive. It later emerges that political prisoners are being tortured in the basement of María and her husband’s house, even as her literary guests carouse and mingle. In the course of one of these soirées a theorist of avant-garde theater—a typical Bolaño plaisanterie—gets lost; he stumbles down various staircases and corridors and then into a room in which he can just make out a blindfolded man tied to a metal bed:

He knew the man was alive because he could hear him breathing, although he wasn’t in good shape, for in spite of the dim light he saw the wounds, the raw patches, like eczema, but it wasn’t eczema, the battered parts of his anatomy, the swollen parts, as if more than one bone had been broken, but he was breathing, he certainly didn’t look like he was about to die, and then the theorist of avant-garde theatre shut the door delicately, without making a noise, and started to make his way back to the sitting-room, carefully switching off as he went each of the lights he had previously switched on.

Unlike this theorist of avant-garde theater, Bolaño sought from the outset of his career to open, and to keep open, his eyes, and his poetry and his prose, to savagery, both as subject matter and as an intrinsic aspect of his conception of what it meant to be an artist. The “savage detectives” of his prize-winning novel of that name are a febrile group of young poets burning the candle at both ends in Mexico City in the mid-Seventies, all of whom end up straying very far indeed from poetry workshops and the groves of academe. The iconoclastic Arthur Rimbaud is their inspiration and ideal, and the founder of the group, Bolaño’s fantasy alter ego Arturo Belano, eventually disappears in Rimbaldian fashion into the African wilderness.

Advertisement

As far as savagery of subject matter goes, I can think of no more grueling, more relentless, more mind-numbing attempt to register the violence from which the theorist of avant-garde theater averts his eyes than “The Part About the Crimes,” the mainly documentary section of 2666 that itemizes, over nearly three hundred pages, the discovery of a seemingly endless succession of raped and mutilated girls’ and women’s bodies in Santa Teresa and the surrounding vicinity in Mexico over a few years in the late Nineties.

Since the publication in English of The Savage Detectives in 2007 and of 2666 the following year, Bolaño has received global acclaim that is in marked contrast to the indifference of the literary world to the poetic effusions of the Rimbaldian tyros whose exploits are so exuberantly and movingly chronicled in the first of his two epics. For Bolaño, being a poet was more an attitude toward life than a question of putting words on a page, and indeed it turns out that Cesárea Tinajero, a stridentist poet of the Twenties with whom Arturo Belano and his poetic detective partner Ulises Lima are obsessed, left behind an oeuvre consisting only of a baffling series of six diagrams and no words at all. We get not one single example of the work of Belano or Lima (based on Bolaño’s friend the poet Mario Santiago, who was killed in a road accident just before the novel was published in 1998) or Juan García Madero, a young “visceral realist” whose diary makes up the opening and closing sections of the novel. “I’ve been cordially invited to join the visceral realists,” runs his opening entry: “I accepted, of course. There was no initiation ceremony. It was better that way.” The following day he confesses: “I’m not really sure what visceral realism is.”

Infrarealism was the name of the movement Bolaño founded in Mexico City in 1976, and it seems to have been an amalgam of Dadaist disruptiveness and Beat revelry, an attempt to recruit a tribe of anarchic troubadours ready to overthrow all forms of bourgeois respectability. They made a nuisance of themselves during readings by Octavio Paz—their chosen representative of “official” Mexican poetry—and advocated a life liberated from all institutions, out there on the open road among “the sharpshooters, the lonesome cowboys,” as Bolaño put it in a manifesto that he read out in the very bookshop from which he had stolen so many of the books that had inspired the artistic revolution he was declaring.

Mexico occupies an odd position in Bolaño’s fictional universe. His family moved there from Chile when he was fifteen, and there are many exhilarating, even paradisal aspects to his recreation in The Savage Detectives of the bohemian literary scene that he became a part of in late adolescence and early manhood. In an essay on Herman Melville and Mark Twain collected in Between Parentheses he talks of the “magic of friendship” that links Huck and Jim in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, a book he elsewhere suggested was his primary literary inspiration for The Savage Detectives.

The friendship between Huck and Jim, he writes, is that of “two totally marginal beings who have only each other and who look after each other without gentle words or tenderness [here he seems to be forgetting Jim’s “honey” and “honeychile” endearments to Huck], as outlaws or those outside the bounds of respectability look after each other.” The intensity of the friendship between Belano and Lima has something of this unspoken, outlaw quality, and the road trip part of the book, its final section, in which Belano, Lima, Madero, and the prostitute Lupe head up to Sonora, both in flight from Lupe’s psychopathic pimp and in quest of the ex-stridentist Césarea Tinajero, has much of the idyllic sense of release and excitement of Huck and Jim’s journey by raft down the Mississippi.

Yet Sonora is also the region in which the serial murders of 2666 are committed, and it features in that novel as an abyss-like hell on earth, the ghastly vanishing point from which all of the book’s many diverse narratives take their bearing. Santa Teresa emerges, to adapt the book’s epigraph from Baudelaire’s “The Voyage,” as the “oasis of horror” to which all paths from the blinding desert lead. Even the elusive but widely admired Central European novelist Benno von Archimboldi, born Hans Reiter, and a veteran, like the rookie, of the savagery of the German/Russian front line, must finally set off for Sonora in order to visit his wayward, sinister nephew who is incarcerated there, and who may—or may not—have played some part in the district’s unending toll of rapes and murders.

Advertisement

Before The Savage Detectives made Bolaño, a few years before his death in 2003 of liver failure, into Chile’s brightest literary star, he returned only once to his country of birth. That was in 1973. Allende was still in power, but only just; General Pinochet launched his coup on September 11 that year, and although Bolaño’s role in resistance activities seems to have been minimal, his Mexican accent aroused the suspicion of officials at a checkpoint, and he was arrested and thrown into jail.

The story of his brief imprisonment is most memorably told in “Detectives,” which is collected in The Return; it presents two cops reminiscing during a car journey about a guy they held prisoner in the wake of the coup—“Arturo I think he was called….” “Yeah, Arturo. He left Chile when he was fifteen and came back when he was twenty.” Arturo Belano, it turns out, had been an old classmate of theirs, “crazy Arturo,” and Bolaño presents his alter ego’s experiences while imprisoned as having played a decisive role in his metamorphosis into the true heir of his half-namesake, Arthur Rimbaud. On his way to the bathroom Belano stopped to look at himself in a mirror, the cop explains to his partner, and “he didn’t recognize himself”:

“That’s all?”

“That’s all; he didn’t recognize himself…. He was in the line, on the way to the bathroom, and as he passed the mirror, he turned suddenly, looked at his face and saw someone else….”

Je est un autre. “Detectives” doesn’t go on to recount the release by the guards of their old classmate, which is apparently what happened to Bolaño after an eight-day incarceration, but focuses instead on his transformation from victim into seer, from coño into Kunst. “Detectives” operates, like so many of Bolaño’s stories and novels, by creating a porous and intriguing interface between autobiography and fiction. The relationship between je and autre is kept constantly in play, like that between Bolaño and Belano.

It turned out, further, that many of the literary bohemians featured in The Savage Detectives were based on real people, which means the book can be read not only as a Twainian buddy novel, but as a Proustian roman à clef, an elegy for a particular circle of artistically-minded friends slowly but inevitably succumbing to the twists and attritions of time. This blending of the documentary and the fantastic is central to the effect of Bolaño’s fiction; his stories, whether freestanding like those collected in Last Evenings on Earth, The Return, and The Insufferable Gaucho, or incorporated into the vast commodious fabrics of The Savage Detectives and 2666, nearly all have a cinéma verité quality, are delivered as fragments of life that are at once resonant and baffling, fascinating and open-ended, beyond clear interpretation or final resolution. Was the rookie’s story true or not? We’ll never know, but it comes over, in its brute randomness and particularity, as an individual’s actual history rather than as a well-crafted fable. The special power of Bolaño’s fiction comes from his ability to persuade us that he is telling it like it is.

Bolaño, like Belano, left Mexico for Europe in 1977 (one hopes he didn’t kill anyone first). In the preface he wrote in 2002 for the belated publication of Antwerp, his first work of fiction—if that’s the right word—completed in Barcelona in 1980, he recalled the state of mind that produced this sequence of fifty-six bitter, drained vignettes that are remarkable only for the occasional detail, and for their stern refusal of both narrative continuity and, more surprisingly, Rimbaldian elation:

My sickness, back then, was pride, rage, and violence. Those things (rage, violence) are exhausting and I spent my days uselessly tired. I worked at night. During the day I wrote and read. I never slept. To keep awake, I drank coffee and smoked. Naturally, I met interesting people, some of them the product of my own hallucinations. I think it was my last year in Barcelona. The scorn I felt for so-called official literature was great, though only a little greater than my scorn for marginal literature. But I believed in literature….

That belief was to sustain him through some tough times, including, possibly, heroin addiction (a methadone cure is eloquently evoked in what appears to be a memoir entitled “Beach”—1988, collected in Between Parentheses—but his widow has suggested that this piece should be treated more as fiction than nonfiction), much aimless drifting (see the piece “Vagabond in France and Belgium” in Last Evenings on Earth), and a succession of menial jobs: dishwasher, waiter, longshoreman, garbage collector, seasonal laborer, receptionist, and night watchman at a campground.

This last features most often in his fiction; one of the three narrators of The Skating Rink of 1993, a not particularly successful tale of obsession and murder, has just this job, as of course does Belano in the middle section of The Savage Detectives. The English student Mary Watson recalls trying to make love with him in his cabin there, but it’s too small for them to lie down, on their knees is too uncomfortable, and on a chair proves impossible. “Finally we ended up laughing,” she records, “not having fucked.” The encounter is thus in contrast to most of those Belano has with women, which tend to elicit what must be the most frequently used phrase in his fiction: “We made love until dawn.”

The preface to Antwerp concludes:

Tacked up over my bed was a piece of paper on which I’d asked a friend from Poland to write, in Polish, Total Anarchy. I didn’t think I was going to live past thirty-five. I was happy. Then came 1981, and before I knew it, everything had changed.

This might refer to his meeting Carolina López, whom he married the following year, but the change took a decade or so to be registered in his writing. “Prose from Autumn in Gerona,” the opening section of Tres, is another sequence of prose pieces; they are dated 1981 and are not markedly different in style or conception or tone from the gnomic fragments of Antwerp. They refer on a number of occasions to the image of a kaleidoscope, and like Antwerp convey a mood rather than tell a story.

Bolaño seems always to have thought of himself as primarily a poet, even after he’d turned into a best-selling novelist. The three sequences collected in Tres, and the selection of his poetry also translated by Laura Healy and published as The Romantic Dogs in 2008, suggest a not always convincing determination to fuse a streetwise, often Beat-inflected idiom with a more avant-garde longing to fragment and disorient, to treat poetry like a linguistic kaleidoscope that will always produce entrancing patterns if shaken vigorously enough.

There is a temptation to see Bolaño’s poetry as a kind of aesthetic “prospecting” that eventually resulted in his discovery of the rich, golden seam of his prose. This may be unfair, although he appears, in the Eighties, to have had no more success than Belano or Lima in making his name with his poetry. He certainly realized that it was unlikely to produce literal gold, and on the birth of his son in 1990, and the discovery that his health was precarious, he decided to see if he might support his family by writing fiction—a lot of it. There are now some twelve novels, novellas, and collections of short stories translated into English, and there are apparently more to come.

Writers, and poets in particular, do, however, bulk large in Bolaño’s fictonal world. The haunting, unnerving Distant Star of 1996 opens at a poetry workshop in Concepción, Chile, just before Allende was unseated by Pinochet. The workshop is attended not only by the gorgeous Garmendia sisters, but an enigmatic dandy who calls himself Alberto Ruiz-Tagle, but is in fact one Carlos Wieder. Shortly after the coup Wieder visits the Garmendia sisters at their aunt’s house on the outskirts of town; they spend the evening discussing the work of such writers as Nicanor Parra and Enrique Lihn (two of Bolaño’s favorite Chilean poets), Sylvia Plath and Elizabeth Bishop. Wieder is invited to stay the night; after the Garmendia sisters fall asleep, he enters the bedroom of their aunt and slashes her throat; the girls themselves are bundled into a car by his henchmen. Veronica’s body is never found, but Angelica’s is later discovered in a mass grave, “as if to prove that Carlos Wieder is a man and not a god.”

Wieder’s own verse appears not only in books and magazines but in the sky as well. He is a pilot—that archetypal hero of far-right regimes—as well as a poet, and he skywrites his terse, uncompromising lyrics—“Death is love,” “Death is cleansing,” “Death is my heart“—while soaring alone in his plane above the city. In a further fusion of art and political violence, he invites select guests to a private exhibition he has organized in the spare bedroom of his flat; it turns out to consist of photographs of the bodies of those he has murdered.

Wieder is one of a gallery of characters who, like Bolaño, believe in literature, yet not, as Bolaño does, as a redemptive escape from the self or as fostering tolerance or understanding of others, but rather as a vehicle for ideological mania. Bolaño’s 1996 collection Nazi Literature in the Americas

1 presents the imagined biographies of dozens of them, from Luz Mendiluce Thompson (b. Berlin, 1928–d. Buenos Aires, 1976), whose most treasured possession is a photo of herself being dandled by Hitler, to an evangelical American preacher, Rory Long (b. Pittsburgh, 1952–d. Laguna Beach, 2017). Long was brought up on Charles Olson and Ezra Pound by his professor father, but discovers true “open” poetry only in the Bible; accordingly he founds the immensely successful Charismatic Church of Californian Christians, on the side writing poems celebrating the longevity of such figures as Leni Riefenstahl and Rudolf Hess. Long will not himself prove as long-lived as his heroes, for we learn that a young African-American called Baldwin Rocha will blow his head off in 2017.2

While there is much institutional and state-sponsored violence in Bolaño’s work, he is also drawn to depicting pure motiveless malignity. The notorious “Murdering Whores,” collected in The Return, might be put in the scales as a counterweight to the hundreds and hundreds of women murdered by men scattered across the Sonora landscape in 2666. It is a monologue told by a woman who has sought out and seduced a Barcelona football fan, then bound him to a chair and gagged him. She is about to murder him with a knife. “It’s nothing personal,” she explains; “You never raped me. You never raped anyone I know. It’s even possible you never raped anyone at all.”

Like “Another Russian Story,” the one concerning the rookie, “Murdering Whores” is as much about art as about torture. The speaker imagines the way her victim would narrate the evening were he to escape her clutches—“Guys you’re never going to believe what happened to me, I nearly got killed, some fucking whore from the suburbs…”; but that story will never be told. The one he will die listening to, unwillingly participating in, is her sinister fairy tale about a princess, a princess without pity, who lured her charming zealous prince, a prince who even gave her an orgasm, into her castle, from which he never escaped.

The two new collections of his short fiction, The Insufferable Gaucho and The Return, often suggest the enormous amount Bolaño learned from Borges, to whom he frequently paid tribute as the greatest of all South American writers. Despite their antithetical public personae—the patient, cerebral, infinitely cunning librarian, the errant, outspoken, insufferable literary gaucho—both Borges and Bolaño seem to demonstrate how artists, or at least certain kinds of artist, must think the unthinkable. In the speech he gave in Caracas (collected in Between Parentheses) on being awarded the 1999 Rómulo Gallegos Prize for The Savage Detectives, he tried to articulate this necessary quality: he called it

the ability to peer into the darkness, to leap into the void, to know that literature is basically a dangerous undertaking. The ability to sprint along the edge of the precipice: to one side the bottomless abyss and to the other the faces you love, the smiling faces you love, and books and friends and food. And the ability to accept what you find, even though it may be heavier than the stones over the graves of all dead writers. Literature, as an Andalusian folk singer would put it, is danger.

Bolaño’s fiction does not, however, depend on fiendish construction or the exploration of disturbing metaphysical conundrums in the manner of Borges. Where Borges is insistently literary and pared to the bone, Bolaño is compendious and expansive, as rich in detail as Dickens or Balzac. I think a clue to his development of the capacious structures he evolved in The Savage Detectives and the extraordinary, overwhelming 2666 can be found in the third of the sequences collected in Tres, “A Stroll through Literature,” which opens:

I dreamt that Georges Perec was three years old and visiting my house. I was hugging him, kissing him, saying what a sweet boy he was.

Perec returns in the final entry, the fifty-seventh, of this sequence:

I dreamt that Georges Perec was three years old and crying inconsolably. I tried to calm him down. I took him in my arms, bought him candy, coloring books. Then we went to the boardwalk in New York and while he played on the slide I said to myself: I’m good for nothing, but I’ll be good at taking care of you, no one will hurt you, no one will try to kill you. Then it started to rain and we calmly went back home. But where was our home?

In his Life: A User’s Manual of 1978, Perec showed how the contemporary novel might emulate the epic sweep of Ulysses, the nested stories of The Arabian Nights. Though never as ludic as Perec, Bolaño found, through the idea of multiple interviews in the middle section of The Savage Detectives, and through the twin foci or magnets of the Sonora Desert and the writer Benno Von Archimboldi in 2666, a means of licensing a similar kind of narrative proliferation. His early work rather rigorously eschewed the art of storytelling, but it turned out to be an aspect of writing that Bolaño was amazingly good at. While he obviously felt that in writing Antwerp he took a long look into the abyss, the book that resulted discloses little of what he actually saw there. 2666 also peers into the abyss; and the stories that emerge in the course of Bolanõ’s vast, rambling, hypnotic magnum opus are among the most enthralling, and unsettling, of modern times.

-

1

English translation by Chris Andrews published by New Directions, 2008. ↩

-

2

The afterlife of the Nazi era is also explored in The Third Reich, a novel drafted in 1989 and found among Bolaño’s papers after his death. (El Tercer Reich was issued in Spanish in 2010; an English translation by Natasha Wimmer will be published in December of this year.) The title in fact refers to a board game, and the novel is narrated through diary entries by the German champion of military board games, one Udo Berger.

It is not, however, hard to see why Bolaño opted to keep this early stab at fiction in his desk drawer, for although it contains some atmospheric set pieces, as a whole the novel fits rather too easily into the well-worn genre of the first-person narrator slowly suffering a crack-up. The ancillary characters—in particular El Quemado, a beach bum who operates a pedal boat franchise and is horribly disfigured by burns, and the enigmatic Frau Else, who runs the hotel on the Costa Brava where the novel is set during Berger’s holiday there with his girlfriend Ingeborg—are rather more interesting than the nerdy central protagonist.

Berger’s battle for world domination with El Quemado, whom he inducts into the mysteries of Third Reich only to find himself suffering defeat after defeat at the hands of his peculiar protégé, is strictly for aficionados of the board game (I must say I wouldn’t have pegged Bolaño as a member of that particular tribe). A macabre denouement is threatened, but in the end the story rather fizzles out. What I would guess the budding novelist learned from writing the book—and from The Ice Rink, composed around the same time, too—was that the novel of obsession, which had proved for a writer such as Nabokov so extraordinarily liberating, was for him more like a straitjacket. ↩