As an actor, he was as simple and unadorned “as a baked potato,” said Katharine Hepburn at a press conference after Spencer Tracy’s death in 1967, and she was like “a dessert, with lots of whipped cream…. He never got in his own way—I still do.”

Meat or potatoes, there was an era when Tracy was regarded as not just the most natural and honest of American screen actors, but the embodiment of unforced morality in our mainstream movies. No one kept count, but Tracy reliably presented men in whom virtue was neither pious nor self-serving. He played these guys calmly, steady in his faith but never cocky about it. Indeed, many of his heroes were battered from their struggle. But Tracy characters did their best and no one doubted their integrity.

That there is no one like him among actors now speaks to what has happened to America as well as to our movies. Perhaps “our” is no longer the proper word. There is so much less shared narrative consequence. There is even a question whether people still watch Tracy’s pictures—as opposed to the partnership of Tracy and Hepburn. The ordinary young viewer may recognize several of the titles those two did as a team, and the legend abides that they were “together” in life (some of the time). But ask the same young person to recall a Tracy picture—Captains Courageous, Boys Town, Man’s Castle, Fury, Bad Day at Black Rock—and he might come up short. So is Tracy simply part of cultural history, or is he still a force in our imagination?

The very size of James Curtis’s definitive new biography is resolute about the answer—1,001 pages on a man who was only sixty-seven when he died, and who made seventy-three pictures. It’s not just that the book is tireless and diligent in its span. No one doubts the author’s fondness for Tracy, or the circle of family and friends who tried to please or humor him. It’s also well written. Beyond that, Curtis has a mission: to rescue Tracy, and even Hepburn, from some of the suggestions that have been passed along, in print and gossip, about them.

Still, the coda to Curtis’s book comes as a surprise, since it is called “The Biographies of Katharine Hepburn,” and is intended to clean our windows. The oddity of this decision is not the authorial indignation at aspersions cast on Tracy’s sexuality, but that the book declines to close with a meditation on what Tracy did and did not accomplish. There is a lasting fascination in the way these two stars “saved” each other and seem to have been more “married” than any other Hollywood couple we can think of. Garson Kanin, who had worked with them a lot, published a memoir, Tracy and Hepburn, in 1971, the start of the legend. Hepburn claimed to be upset. If Spence had lived, she said, Kanin would never have dared! But in 1971, the public was still innocently inclined toward affection for movie stars. Nowadays, the love is very fickle, and it is prodded by malice, envy, and a need for revenge.

Spencer Bonaventure Tracy was born in Milwaukee in 1900, of Irish and Catholic stock. An early girlfriend found him spellbinding—“He could tell you black was white, and even if you thought he was wrong, pretty soon he’d have you believing him.” She added, “Of course, he was as homely as a mud fence.” More than that, the family pictures in Curtis’s book suggest that Tracy was never truly young, let alone open or uninhibited. So the charismatic young man would develop a wry, suspicious face, seldom exuberant or romantic, leaning on a great need to be straightforward.

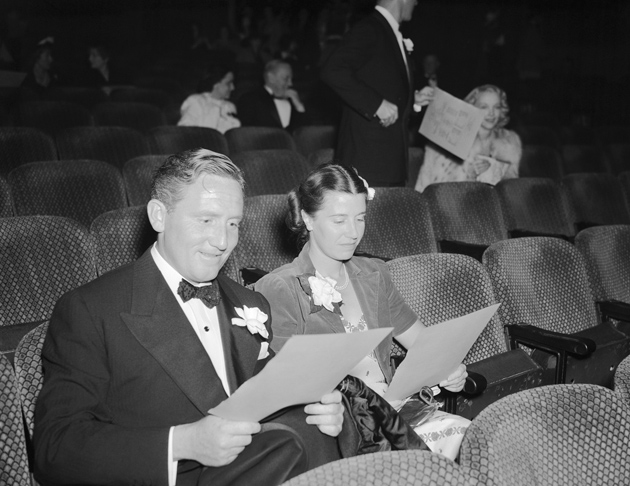

Years later, when they came together to make Woman of the Year (1942), Katharine Hepburn noticed similarities and gaps between them—Hepburn was always in her own muddle whether she could, or should, look like a beautiful movie star. “His ears stuck out,” she said. “And he had old lion’s eyes. And he had a wonderful head of hair. And a sort of ruddy skin, really like mine. I mean, he was not as freckled as I am, but he was ruddy. And…[a] nice mouth.”

They were often at odds, but usefully so. When they were introduced, on the MGM lot, by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, she is supposed to have said, “I might be a little tall for you, Mr. Tracy.” The legend goes that Mankiewicz responded, “Don’t worry, Kate. He’ll cut you down to size.”

That sounds like Mankiewicz (the writer-director of All About Eve), but by now it’s so much a part of “Tracy and Hepburn” that we assume the actors made up their lines. Tracy preferred a few takes after a lot of brooding; Hepburn was all for rehearsal and discussion. She was outspoken, he was reserved, and teasing was their common trait. But teasing is important in life, and the secret to their films was their needling rivalry. She was the big talker, always ready to rewrite the script, while Tracy did as he was told. One way or another, Hepburn served as unofficial producer on several films. Tracy never once said to the studios that made so much of him, “Let’s do that!” He was keenly watchful, yet he didn’t care to direct the way audiences might see a thing.

Advertisement

Tracy is not exactly the personality you would imagine going into acting—I think a part of his appeal lay in matching the widespread conservative feeling that films and stardom were foolish, fanciful, and even dangerous, not the sort of thing solid Midwest citizens did. But he loved public speaking, and Tracy’s genius was promoted by sound. His rough, tender voice was his most reliable tool. Like Gary Cooper, Tracy liked to shorten lines, and he preferred to read them according to a hidden purpose. In his own language, he reacted and strove not to do too much. He wanted to make a word feel as powerful as a glance. After the stormy signaling of silent pictures, the huge bonus of talking pictures was in allowing actors to be quiet. The inner life was opened up, so now we can all do our close-ups meant to signify “thought.”

But the inside of Spencer Tracy was not a tranquil place. Perhaps that’s why he felt it so deeply. The very apt jacket of Curtis’s book is Irving Penn’s portrait of Tracy jammed in a white corner, his legs crossed, a fist guarding his mouth, his gaze daring the camera to take the picture.

In 1923, on a train going to White Plains, Tracy saw an actress a few years his senior named Louise Treadwell. Curtis starts his book with this scene, as if to say the marriage that followed was crucial. If so, it may have been a burden and a duty in which Tracy believed he failed. Louise gave up her career at first to look after him (later on Hepburn would serve as nurse and booster to his ups and downs), but he was often unreachable. Curtis’s book, making use of Tracy’s own journals, shows how earnestly he pursued his career. But was he ever persuaded by it? Tracy could be a fearsome binge drinker who often holed up in hotels. He used prostitutes and sometimes got caught up in violence. By current standards, he seems an obvious depressive.

He and Louise had a son, John, who they realized was born deaf. Curtis wants to stress this was not because of Tracy having a venereal disease. John was the victim of a recessive gene disorder passed on by both parents. But this was learned only after the actor’s death, and there’s no reason to doubt that Tracy wondered whether his own sexual habits had struck at the son; his wife devoted herself to the John Tracy Clinic for the deaf and lived largely apart from her husband. Look at the Penn photograph, look at some of the best Tracy films, and it’s hard to think of a movie star closer to worry and guilt yet so anxious to convey stability.

Curtis has ugly and fearsome portraits of Tracy overwhelmed by drink, and we realize how often the good man he aspired to be failed him. The biography has a meticulous yet understanding account of how the actor’s indecision, dishonesty, and lack of courage undermined his return to the stage in 1945—in Robert E. Sherwood’s The Rugged Path—and justifies the playwright’s rueful verdict when that show folded. When asked to make efforts to save the show, Tracy was no help at all. Sherwood told his principal backers, “I bitterly regret the initial mistake that I made when I put my faith, and the fruits of long labors, in one who had proved, over and over again, that he possesses the morals and scruples and integrity and human decency of a louse.” Curtis doesn’t argue.

There are other ways Tracy might have gone. After work in provincial theater in the 1920s, and having a big stage success as a prisoner on death row in The Last Mile, he was in movies by 1930, and working hard. In 1933, for First National and Warners, he made 20,000 Years in Sing Sing. It’s a fast, entertaining prison picture (directed by Michael Curtiz, who would do Casablanca ten years later) about Tommy Connors, a smart young gangster who goes to the chair eventually to save his girlfriend. It has first-class scenes with the prison warden, full of Tracy’s scathing but fond irony, and it has Bette Davis as the girl. “For the run of the picture,” Davis would write, “we had this wonderful vitality and love for each other.” And it shows. Soon enough, Davis would become so much an icon and so strong that only mild actors could play with her. But 20,000 Years is charged with an energy that Tracy shows no wish to restrain. He and Davis never got to make another film together. Katharine Hepburn had arrived in Hollywood at much the same time.

Advertisement

Tracy had several affairs in the 1930s, and thought seriously of marrying Loretta Young, his costar in Frank Borzage’s lovely Depression romance, Man’s Castle, though they were among the most devout Catholics in town. (Tracy nearly rejected the lead role in The Last Mile because his convict had to attack a priest.) Later on, he had a serious fling with Ingrid Bergman, aroused perhaps by the sado-masochistic eroticism they discovered in Victor Fleming’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Ten years after that, there was a passionate relationship with Gene Tierney, no hint of which shows in the dreary film they made, Plymouth Adventure.

Any actor in the 1930s had to play love scenes, and Tracy did his bit with Luise Rainer in Big City and Joan Crawford in Mannequin. But it’s striking how far his screen persona stayed away from romance, or had no pressing need for it. He has a girlfriend (Sylvia Sidney) in Fritz Lang’s American debut, Fury (1936), but it’s a film about a man scorched and warped by injustice and fixed on revenge—it is really the first film in which Tracy’s moral sternness comes across. He played a priest in several big hits—San Francisco, Boys Town, and Men of Boys Town. He was essentially Clark Gable’s buddy in Test Pilot and Boom Town. He was an outdoor adventurer in Northwest Passage and Stanley and Livingstone, and in Captains Courageous (from Kipling, and Tracy’s first Oscar) his real costar was the boy, Freddie Bartholomew, while he played a humble Portuguese fisherman, with an accent and darkened skin. Captains Courageous was beloved in its day (1937), yet it plays rarely now, as if its unabashed self-sacrifice could no longer keep us from impatience.

By 1940, Tracy was a major star who often seemed older than his real age. He had a tendency to put on weight, and a slowness or gravitas had become habit. In an age of Tyrone Power, Errol Flynn, and Robert Taylor, Tracy was headed away from glamour and charm. Hepburn was even more of a problem. Only a few years earlier, she had been labeled “box-office poison” in the Hollywood Reporter after “flops” like Bringing Up Baby that are now recognized as masterpieces. There was talk that Hepburn was gay. Above all, there was talk from Hepburn herself. She could never bridle her own intelligence and opinions, though the business believed that her eloquence and classy voice felt threatening to both men and women in the heartland audience.

Woman of the Year was the turning point, and it should be noted that the script and its writing (by Ring Lardner Jr. and Michael Kanin) was helped along by Hepburn just as, with Howard Hughes’s backing, she had set up the Philip Barry play The Philadelphia Story for herself. But the original plan for this film was for the woman to surpass the man. This was the way George Stevens directed it, after Hepburn had maneuvered to get Tracy playing opposite her.

When MGM screened this version, even Hepburn agreed it didn’t work. She admitted this to her unexpected buddy, studio boss Louis B. Mayer (another teasing relationship), and accepted a new ending. As George Stevens saw it, they went back to the model of The Philadelphia Story, in which there was

a woman so superb…so everything, that she antagonized every woman in the audience, because this is superwoman. Philip Barry wrote the play in which she got her comeuppance, and the audience loved a comeuppance, loved her for taking it, and this was the start of Kate’s second career.

So Woman of the Year is striking and unprecedented in its feminism, until it’s not—when the superior woman agrees to become a housewife in distress. But the film flourished; it launched a team and proved a clever resolution to the limits facing two screen stars. I don’t mean to say that Hepburn contrived the whole thing, though knowing what was best for others was not foreign to her nature. There’s no doubt about the love between them, or some sex, yet I don’t see them as Burton and Taylor. Of course they were in bed together, but perhaps Spence fell asleep listening to Kate talk. It’s no sign of malice or diminution for Tracy, but the teaming let Hepburn soar while it placed Tracy in his own grumpy isolation.

Altogether the pair made nine films, from Woman of the Year to Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967). They are not all good: Desk Set, Without Love, and The Sea of Grass (directed by Elia Kazan) have not lasted, and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner has its heart in the wrong place—where the head should be. But Keeper of the Flame, Adam’s Rib, and Pat and Mike (all directed by George Cukor) are still pleasures. Adam’s Rib (1949) is the most characteristic: it has a married couple who become competing lawyers, with a screenplay by Garson Kanin and Ruth Gordon—important figures in the Tracy-Hepburn circle—and it has a tour de force performance by Judy Holliday. But Keeper of the Flame (1943) may be the biggest surprise: it’s the drama of the widow of a right-wing powerbroker, with Tracy as the journalist investigating the man’s misdeeds. Hepburn was never so beautiful, or Tracy so gentle, but the film (written by Donald Ogden Stewart) is a rare wartime reflection on the chance of fascism in America.

Apart from these films, Tracy’s career faltered if he was not cast as a normal, fond, but mortal father figure: he was ideal as Dad to Elizabeth Taylor in Father of the Bride and Father’s Little Dividend, and he had a similar bond with Jean Simmons in The Actress, loosely based on Ruth Gordon growing up. But he was far from an action actor, so it proved an unhappy decision to be involved with a pretentious metaphor for manliness, the film of Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea (1958). Tracy feels so horribly far from Hemingway’s bogus archetype: a plump, sunburned, boozy tourist trying to sit in an early blue-screen, back-projected epic that was beyond filming, or rereading. Still, he was so revered that the overbudget effort obscured the result: he was nominated once again—there would be nine Academy Award nominations in all.

The glory of Tracy’s last years (for some of us) is not in the Stanley Kramer films he made (Inherit the Wind, Judgment at Nuremberg, It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner) but in Bad Day at Black Rock (1955). Tracy had to be talked into that film, and he is not the most likely to play the one-armed investigator of a certain age who handles Ernest Borgnine and Lee Marvin in their loutish primes, and then Robert Ryan. But the story is exceptional, and Tracy understands its dignity without need of solemn speeches. The desert setting is beautiful, pitiless, and toxic—it’s biblical. The small incident swells naturally in significance and it relies on Tracy’s dry stoicism, old already in his mid-fifties and committed to a difficult duty.

Curtis understands much about Tracy, but his book doesn’t heed Tracy’s instinct to cut rich material and say the minimum. Still, I marvel at the research (based on family support, especially from the daughter, Susie, and benefiting from early work done by Selden West). Curtis is angry with writers who assume that Tracy could have been bisexual, and he insists that in six years he has found nothing to challenge the heterosexual probity (and recklessness) of this unhappy man. Does it matter now? Bisexuality in Hollywood has not been uncommon; unhappiness in actors may be their spur. It’s clear that Tracy’s grim assurance onscreen was his best peace in life.

His sexual adventures are of less importance than the following kind of observation from Curtis. It’s a way of writing that justifies the labor of the book, that penetrates the wounded decency of Tracy, and may send us back to the screen. It concerns the moment in Woman of the Year when Hepburn’s character gets Tracy to drive her to the airport. “Why am I here?” he asks her, and Curtis answers:

And when she catches her breath and says, “I thought you might want to kiss me good-bye,” Tracy calmly takes it in, processes it, then turns himself away from the camera, ostensibly to glance down the terminal corridor, but also to make sure the most significant kiss of his entire career takes place completely out of sight of the audience. The camera moves in, Hepburn in profile as he draws her towards him, her lips apart, the moment of contact perfectly obscured by the brim of his cocked hat. It is brief but heartfelt, passionate and completely unencumbered by concerns of lighting, position, focus. It’s the back of his head, her chin, the muffled soundtrack, their eyes laser-locked on each other as he releases her. It’s as real as any kiss in the history of the medium, the look of astonishment on her face, the deadly serious look on his, screen acting at its finest…if it was acting.