The following is by an Iran expert who wishes to remain anonymous.

Two years ago, Iran’s ruling ayatollahs united to save the presidency of the fraudulently reelected Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, after he was challenged by hundreds of thousands of protesters intent on removing him and building a more democratic Iran. Ahmadinejad survived and the Green Movement, as the opposition was called, was crushed. Thousands of people were arrested, and many were tortured; more than a hundred were subjected to a televised show trial; and dozens were killed in the crackdown. The clerical establishment, which has considerable sway over the government through the Supreme Leader and the various councils and other bodies that answer to him, ultimately supported the vote counts on which Ahmadinejad based his victory.

Since then, however, Ahmadinejad’s alliance with the clerics has been torn apart by a controversy over religious doctrine. The chief disputants are Ahmadinejad and his former patron, the country’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. But the man who has provoked the rupture is Esfandiyar Rahim Mashaei, President Ahmadinejad’s chief of staff and close adviser, a lay revolutionary. In defending Mashaei, Ahmadinejad has suffered repeated insults and challenges to his authority. The mullahs who make up the country’s conservative establishment hate Mashaei because he is reputed to be in contact with the Twelfth Imam—a messianic figure who, according to the dominant branch of Shiism, has been in a state of “occultation” (in effect, hiding or concealment) since the tenth century.

The ramifications of Mashaei’s alleged “gift” of having relations with the Twelfth Imam are enormous. Most Shia Muslims endorse a dynastic line of claimants to the leadership of Islam that began with Ali, the Prophet’s cousin and son-in-law, who was elected caliph in 656 and murdered five years later. There were eleven more of these hereditary imams, or guides, and all but one of them met a violent death at the hands of their enemies—the forebears of today’s Sunni community, who had rejected the dynastic principle and established their own caliphate. According to the Shia tradition, in 941 the Twelfth Imam was occulted, promising to reveal himself at an unspecified moment in the future to end vice and confusion.

The prospect of an infallible imam who might return at any moment (having miraculously retained his youth) holds obvious attractions for an embattled minority religious community, and the history of Shiism is full of controversial figures who have alleged—or let it be alleged on their behalf—that they have met the Twelfth Imam. But these claims are a challenge to Shia clerics, who regard themselves as the rightful intermediaries between God and the community. What if someone from the community claims to be in direct contact with the imam, and can transmit his wishes to society? In that case, the clergy becomes superfluous. According to one prominent conservative, Ayatollah Muhammad Taqi Mesbah-Yazdi, Mashaei has “bewitched” his friend President Ahmadinejad—and Shia mullahs do not bandy about such words metaphorically.

The example of the Baha’i religion shows the dangers that can arise from the combination of a self-proclaimed divine and a receptive populace. Baha’ism originated in the teachings of a nineteenth-century Persian savant who called himself the Bab—the “gate” leading to the Twelfth Imam. The Bab was executed in 1850, but not before setting off violent disturbances by his supporters that greatly worried the clergy—and the ruling dynasty. Until the 1979 revolution that toppled the Shah, the Baha’is were subject to intermittent repression; those who did not flee after 1979 have been persecuted and, in numerous cases, killed.

To understand how a sophisticated country whose recent protest movement seemed grounded in rationalist ideals could fall prey to such quackery, it is necessary to grasp the tragically strange position in which Iran finds itself. Heterodox theology and millennial visions thrive in places where conventional means for dissent have been closed down, and where large numbers of people feel alienated and confused. Both of these conditions apply in today’s Islamic Republic. Most observers would agree that Iranians are now more disoriented and unhappy than at any time since the 1979 revolution. That view has become an axiom, underpinning any number of the recent conversations that I have had in my hometown, Tehran. A common complaint is that “nothing is where it should be”; the natural order of things has been disturbed.

The Revolutionary Guard, for example, was once Iran’s elite military force. Now it is that and much more. The Guard crushed the protests of 2009 and 2010, its ships patrol the Persian Gulf, and its agents combat the “deviant current,” by which they mean any form of dissent that also claims Shia legitimacy. The Guard’s biggest expansion has been economic. In the absence of foreign investment, the businesses run by the Guard have achieved dominance in road-building, telecommunications, and the country’s sole export industry of note: oil and gas. The recently appointed oil minister came to the job from a huge, Guard-owned conglomerate that has $25 billion worth of contracts with his new ministry.

Advertisement

The combination of an oppressive regime and crippling sanctions, meanwhile, has isolated the country and produced a strong sense that Iranians are on the margins of the world. The international sanctions imposed under US leadership, along with various acts of sabotage and the assassination of Iranian physicists (three to date, one of whom was shot in front of his house in Tehran by a passing motorcyclist in July), have slowed Iran’s nuclear development—though the country continues to expand its inventory of ballistic missiles, some of which would be capable of carrying a nuclear payload.

After nearly a decade of diplomatic activity, and much speculation about the possibility of an Israeli attack on Iran’s facilities, the aim of the Iranian program remains obscure. Last February, President Obama’s director of national intelligence told Congress, “We continue to assess [whether] Iran is keeping open the option to develop nuclear weapons…. We do not know, however, if Iran will eventually decide to build nuclear weapons.”* In its most recent report on Iran—published on September 2, 2011—the International Atomic Energy Agency wrote that it is “increasingly concerned about the possible existence in Iran of past or current undisclosed nuclear related activities involving military related organization, including activities related to the development of a nuclear payload for a missile.”

To make matters worse, outside Iran’s borders, in several Arab countries, there are signs of movement, dynamism, and hope. The authorities boast that the freedom-seeking Arabs have been inspired by Iran’s 1979 revolution—with the exception of Syria, Iran’s key regional ally, whose protest movement is depicted in the state press and television as a creation of the Western powers.

In this confused state of affairs the President’s pal Esfandiyar Rahim Mashaei has acquired fame and notoriety. Confident, impressive-looking at the age of fifty-one, Mashaei has been close to Ahmadinejad since the late 1980s, when both served as young officials in the northwestern province of Kurdistan. The friendship prospered as Ahmadinejad rose to power as mayor of Tehran. When Ahmadinejad won the presidency in 2005, Mashaei became head of Iran’s Cultural Heritage Organization, and in 2008 Mashaei’s daughter married the President’s son. But Ayatollah Khamenei and his conservative supporters have long suspected Mashaei of holding unorthodox beliefs and of encouraging the President in his reportedly anticlerical views. So when it became clear that Ahmadinejad, who must stand down in 2013, was grooming Mashaei to be his successor, the Supreme Leader intervened.

Shortly after the rigged election in 2009, Ahmadinejad named Mashaei to be his vice-president, but Khamanei revoked the appointment, and since then, though Ahmadinejad has retained him as chief of staff, Mashaei has been the object of much vilification. Prominent conservatives have linked him to the “deviant current” that threatens to overwhelm the country. More than a dozen of Mashaei’s associates—including government officials—have been arrested, and have been described by one Khamenei supporter as “financially and ideologically corrupt.” Ahmadinejad has been subjected to immense pressure to abandon his adviser, but he has not succumbed. Mashaei remains chief of staff, and in September he accompanied the President on his annual trip to attend a meeting of the United Nations General Assembly in New York. The President’s loyalty has prompted further speculation about the hold that Mashaei has over him.

Mashaei is certainly a fascinating figure. He combines an irreverent disregard for revolutionary shibboleths with a reputation as a seer. He has spoken in conciliatory terms of the people of Israel (as opposed to the state they live in), asserting that Iranians are “friends of all people in the world—even Israelis.” He uses nationalist slogans that challenge the Muslim internationalism that is part of the official ideology, and he has been criticized for controlling parts of the government. In 2010 he paid a controversial visit to Jordan’s King Abdullah II—who has spoken of Iran with hostility—at Ahmadinejad’s behest.

Mashaei presents a more moderate demeanor than his boss, who in 2005 suggested that Israel should be wiped out, but Ahmadinejad seems to like having someone in his entourage who sets himself against the moth-eaten orthodoxies of the old guard, which emphasize the wisdom of Khameini and the authority of the clergy. The reason is that even among Ahmadinejad’s constituency of poor, pious Iranians, these orthodoxies no longer seem like the summit of wisdom and good sense.

The Islamic Republic is used to suppressing secularists (such as the Green Movement), Communists, and monarchists; Mashaei’s combination of millenarianism and presumed anti-clericalism, which is regarded as a covert assault on the Islamic Republic, is harder to demonize. For one thing, most people are tired of time-serving clerics getting all the plum jobs. The image of the venal mullah is well- entrenched. Second, the regime has itself encouraged mass devotion to the Twelfth Imam, lavishing attention in the mass media on his mysterious ways and building a vast devotional complex at Jamkaran, a shrine complex an hour and a half’s drive from Tehran, where he is expected to make his triumphant reentry to earthly affairs. Millions of pilgrims each year visit Jamkaran and other sites associated with the Twelfth Imam. Their evident desire is to hasten his return. As a well-known modern poem puts it:

Advertisement

There is news, news is on the way;

Gladdened is the heart that is aware of it;

Perhaps he will come this Friday—perhaps;

Perhaps he will pull away the cloth that hides his face.

An important assumption underpins this state-sponsored devotion: if anyone in the Islamic Republic enjoys the particular favor of the Twelfth Imam, it is the Supreme Leader. But Ahmadinejad and his cronies seem to be challenging Khamenei’s prerogative. Earlier in his presidency, Ahmadinejad was reported to have said, “I am not the Supreme Leader’s president. I am the president of the [Twelfth Imam].” (The President neither confirmed nor denied these allegations.) A recent documentary film called The Return Is Imminent, which was distributed widely in the form of a free DVD, identified Ahmadinejad’s leadership of a great army as one of the conditions for the imam’s reappearance. (This led to the arrest by the judiciary of several people associated with the film, including another presidential aide.) According to a current rumor, Mashaei has occasionally been seen with his eyes closed, communing with the Twelfth Imam. The secular middle classes scoff, but many others are impressed.

Above all, the conservatives fear attempts by members of the “deviant current” to use their ostensible piety as a cover to challenge yet another revolutionary orthodoxy. This is what the pro-Ahmadinejad newspaper Iran is accused of having done on August 13, in a supplement devoted to women’s issues. The target of Iran’s criticism was the mandatory Islamic covering for women, the hijab.

The Supreme Leader has repeatedly declared the chador, a long garment (usually black) that pious Iranian women wear, to be the best form of hijab—better, for instance, than alternatives such as a coat and headscarf. For many women, however, including some supporters of the Green Movement, the chador is a graceless covering that symbolizes their submission to unjust and discriminatory laws. So Khamenei’s supporters were furious when Iran deprecated the black chador in the pages of its supplement, denounced “extreme” views on the hijab, i.e., insisting on the chador, and made fun of the “guidance” patrols whose members arrest immodestly dressed women in the streets.

The conservative reaction was virulent. The judiciary, controlled by Khamenei, issued a writ against the newspaper and one ayatollah deplored its “promotion of chaos.” The head of the cultural institute that runs Iran predicted that he and his colleagues would be convicted of apostasy and sentenced to death “for a sin we did not commit.” Although Mashaei has no official role at Iran, he was quickly associated with the views endorsed in the supplement and a preacher promised to reward anyone who killed him. Mashaei is now implicated in a fraud and embezzlement scandal, which led to the recent resignation and disap- pearance of the head of the country’s biggest bank, while some parliamentarians are maneuvering to try to impeach the president. Khamenei, as the Supreme Leader, would certainly prefer the less incendiary option of seeing out Ahmadinejad’s last two years in office and guiding him into retirement. But power struggles in Iran do not always end so innocuously.

—October 12, 2011

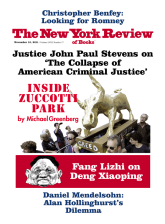

This Issue

November 10, 2011

Our ‘Broken System’ of Criminal Justice

The Real Deng

In Zuccotti Park

-

*

In June, six European ex-ambassadors to Iran, including the former envoys of Britain and France, publicly doubted the entire rationale behind the sanctions regime. In a remarkable article published in The Guardian, they questioned the assumption that Iran constituted a threat to peace and suggested that the West’s “unrealistic” insistence that Iran abandon uranium-enrichment had “contributed greatly to the present standoff.” It is worth noting that Britain and France have so far been the United States’s staunchest allies on the Iranian nuclear question within the United Nations Security Council. See Richard Dalton, “Iran Is Not in Breach of International Law,” The Guardian, June 8, 2011. ↩