At the Museum of Modern Art’s Willem de Kooning retrospective, the gift shop is selling a mug that has on it this quote from the artist: “In art one idea is as good as another.” The line is typical of the thoughts one finds in de Kooning’s published statements and recorded remarks in that it is at once funny, a little shocking, air-clearingly down to earth, and makes you see things a little differently. De Kooning’s point was that you could take an idea and suddenly see any number of heretofore unrelated artists being connected to it. But the words also suggest that it is not the artist’s theme that is the point but how it is brought off. Like many of de Kooning’s statements and sayings, the sentence delivers a human and artistic truth that tends to get lost when curators, critics, and even artists, in their public statements, talk about art.

In another light, though, de Kooning’s thought flattens differences, and the line came back to me as I tried to square the technical brilliance and almost grueling intensity of much of the work on view at the Modern with a sense of stasis and ungraspability it can leave you with. In a working lifetime that stretched from the late 1920s to almost the late 1980s, de Kooning (who died in 1997, at ninety-two) was almost programmatically elusive. He continually blurred the distinctions between abstraction and representation, and his individual pictures can be at cross-purposes as well. His best-known images, of seated women, from the early 1950s, are cauldrons of violent brushwork, but the overall tenor of the pictures is a lampoonish deflating of that brushwork. He held, as he noted in relation to Mondrian, that trying to attain a distinct style is a “horrible idea.” He wrote that when he read Kierkegaard’s line “To be purified is to will one thing,” the words “made me sick.” But then he was also a great admirer of Kierkegaard—and of Mondrian.

De Kooning’s refusal to take sides was held against him, especially in the 1950s, when abstract art was riding high in New York. Now, however, when the notion of a single vanguard style has become inconceivable to most artists in their fifties or younger, de Kooning’s relativism may make him seem more our contemporary than many of his fellow Abstract Expressionists—Barnett Newman, say—who adamantly willed “one thing.” And it may be the indeterminacy of his art that makes it, for this viewer, at least, more cerebral and psychological than emotional in its force. It presents something cool and colorless: the workings of a consciousness.

With his taste for contrary thinking, de Kooning might be tickled by this comment since color, taken literally, is, as he was certainly aware, one of his great strengths as a painter. And at the Modern’s retrospective, the first comprehensive look at the artist since his death, the wealth of color and texture, the physical energy, and the formal thinking on display happen to be astounding. In his later years, de Kooning’s art lost some of its intensity. Yet to the end of the exhibition, the largest gathering of his work ever, we are excited to be in the presence of an artist who, in his feeling for shape, space, color, brushwork, ways to draw, and how a painting’s surface is to appear, never stopped reinventing himself. The show, organized and installed with a fine straightforwardness by John Elderfield, will, I think, hit artists and nonartists in the same way: as a demonstration of resolute, heroic striving and of the ever-changeable properties of painting itself.

It mirrors a life, told in Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan’s discerning and insightful de Kooning: An American Master (2004), that had the operatic largeness, and the outsize personal difficulties, we associate with the Abstract Expressionist era. The Dutch-born painter, who came to New York as a penniless stowaway in 1926 (and remained wary of authorities for years from fear of being deported), eventually became a cult figure in the city’s then small art world. He was known as a tireless worker who was rarely satisfied with his pictures, kept redoing them, and destroyed many along the way. He didn’t feel he was ready for an exhibition until 1948, when he was forty-four.

This first show came at a time when a number of painters, including Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, were also either first showing or were making what would come to be considered their distinctive work. Their efforts were met with serious critical attention and, not long after, coverage in national news magazines, museum interest, and eventually a new breed of collector. By the early 1950s, New York’s art scene began to be pervaded by a degree of money and publicity that was new to it and could be deeply unsettling. It seemed to exacerbate Pollock’s drinking problem, and that, along with difficulties in advancing his work, probably led to his relatively early death, in 1956, when he ran his car off the road. Perhaps it was the acclaim that now waylaid de Kooning. His own binge drinking, begun at the time and described in grim detail in Stevens and Swan’s biography, could leave him passed out, with the night spent literally in the gutter.

Advertisement

The heavy drinking persisted without letup after he left New York for Springs, on Long Island, in the early 1960s. There he worked to create a new home for himself. It was essentially a vast studio, with the living quarters a bit of an add-on, and he kept redoing the place as he went along, exactly the way he painted. In the 1980s, he was hit by an Alzheimer’s-like dementia. It eventually overwhelmed him completely. From the late Eighties until his death ten years later he lived in its shadow. And it added a second dilemma in making people question the authorship of the paintings he did in the years leading up to the time when he finally stopped working.

Yet in crucial ways, de Kooning was quite different from his fellow Abstract Expressionists. Even while his psychic and physical health was endangered from the mid-Fifties on—and he went, sometimes messily, from one romance to another (and was all the time married to the painter Elaine de Kooning, and had a daughter, Lisa, with Joan Ward)—he never lost sight of his profession for long. Perhaps because he got his start as a commercial artist, often doing store windows and lettering jobs, first as a young man in Rotterdam and then after he came to New York, he didn’t see art in anything like the transcendent terms that Pollock, Rothko, or Newman did. He didn’t, like them, operate as if he needed to make pictures that had no ties to earlier ones or that announced that art was beginning anew.

De Kooning wanted to make a radically new kind of art, but he was in love as well with the museum. The working method he eventually devised echoed two of the principal approaches of modern art: Cubism, where an image is broken into many separate parts, all seemingly right on the surface of the work, and collage, where a picture can be a collection of disparate elements. His images were arrived at, however, intuitively. He often seems to have started with some idea of a standing or seated figure, or with shapes derived from the body, and then to have been guided by his feeling for craft—for where his brush wanted to go—and by what his instincts were telling him.

His goal wasn’t a self-psychoanalysis. But his pictures are on some level examples of free association. They might wind up showing a fleet of shapes streaking in a direction, or they might show an interlocking of shapes where some clearly suggest teeth, say, or a thigh or a window—or they might be more figurative than abstract, and give us women as ogres, queens, babes, or screaming meemies. A perfectionist who didn’t know from day to day where he was going, his approach kept him in a state of continually readjusting shapes, trying them in new places, wiping them out, and beginning again. Yet the finished works look as if they had either just come together the second before or are still in the process of finding themselves.

Whether a majority of de Kooning’s pictures appear to be essentially abstract, or whether there are more that seem figurative, is hard to say. But the works that give us more to chew on are often those where the figure is visible in some way, and in them de Kooning has a distinct, tangible subject. His theme, shared with a number of what might be called second-generation modernists—artists such as Alberto Giacometti, Philip Guston, Louise Bourgeois, and Francis Bacon, who like de Kooning were born in the early part of the twentieth century and grew up with the achievements of the great pioneers of modern art ringing in their ears—is about coming to live in an altered terrain. It is about understanding and accepting the challenge and necessity of, specifically, abstract art while feeling at the same time that tradition, or the past, or representational imagery, or, in Bourgeois’s case, one’s own life story, cannot be dispensed with.

The results were so many pressurized, almost crazed kinds of representation, with the human figure emerging in Giacometti’s sculpture as a weathered miniature and in Bacon’s pictures as a blur in a sleekly bare showroom. For Bourgeois the figure was ultimately a stuffed and sewn dummy in a vitrine, while for de Kooning’s fellow Abstract Expressionist Guston, whose changeover from painting abstractly to representationally was an ordeal that took place over years, the figure turned out to be a race of cartoon Klansmen and lumbering characters who look like Mr. Potato Head.

Advertisement

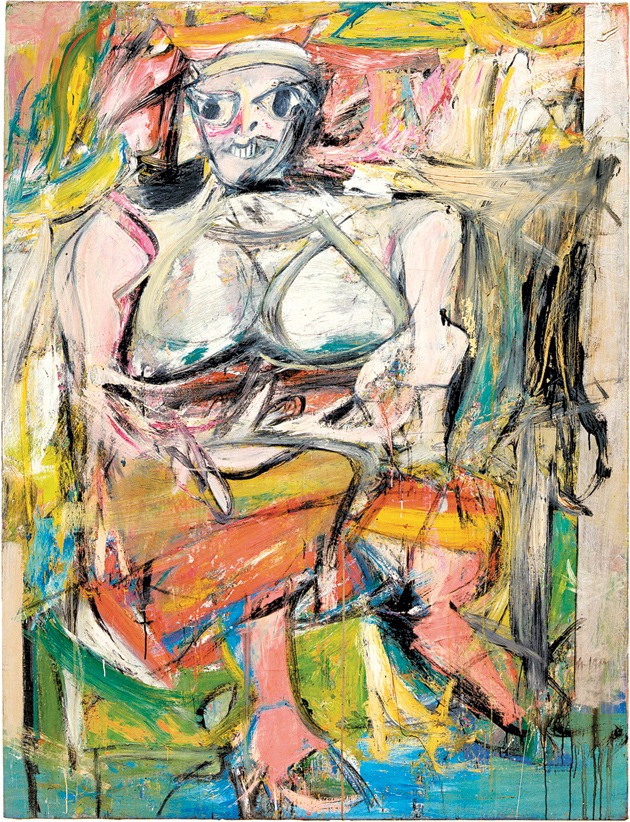

De Kooning’s version of this crazed entity, and his most momentous and well-known creation, are his Woman paintings of the early 1950s—images of monster gals with bulging insect eyes, huge grinning mouths, and ample breasts. Equally ferocious and inane, these figures, seen in the exhibition in a handful of paintings and numerous works on paper—and most impressively in Woman I (1950–1952), perhaps his most complex and forceful single work—remain after more than half a century amazing imaginative leaps on the part of the artist. They appear about halfway into the exhibition, and a viewer can feel that they bring to a boil the many different kinds of pictures that come before them.

This is not to say that de Kooning’s earlier work forms merely a preamble. Taking in those paintings and drawings, beginning with rarely seen still lifes from the late 1920s, is the most absorbing part of the exhibition. In the many works on view from these years, de Kooning hardly ever seems to repeat himself. His first really mature paintings, dating from the 1940s, are of single figures in often bare spaces. They are delicate, high-strung works where the pencil-thin delineation of the figures and their clothes is made to hold its own against expanses of heady pinks, yellows, lavenders, orangey-reds, bright and luxuriant blue-greens—colors that still seem both fevered and ornamental. Suggesting what might be called decorator colors (and colors we associate more readily with the jazzy designer tones of the 1950s), their appearance gives the first flash of the de Kooning who liked to do what serious, “fine” artists were not supposed to do.

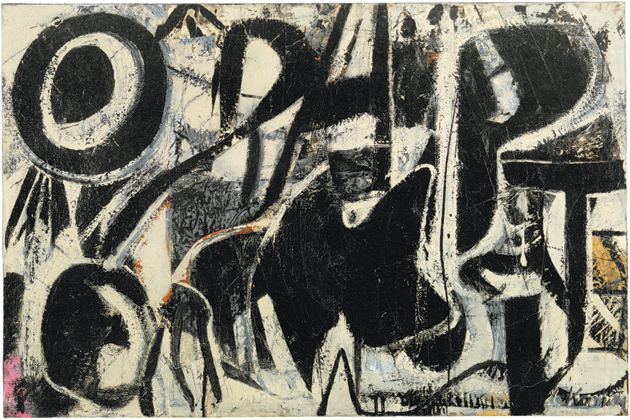

Yet the stylized, protuberant eyes de Kooning gives the figures detract. Too reminiscent of the haunted eyes found in Depression-era graphics, they make these people look like neurotic puppets. His subsequent black-and-white abstractions of the late Forties and early Fifties, on the other hand, lack some human element. These paintings, which show shapes tumbling around like clothes in a washing machine, and the huge, grandly conceived 1950 Excavation, where a world of shard-like white shapes are locked together, have been treated as masterpieces from almost the moment they appeared, and they could be called perfectly realized works. In them, rounded and jagged shapes—and, in the superb 1947 Orestes, stylized letters from the alphabet—come together with uncanny rhythmic ease. With their beckoningly gritty and gleaming surfaces, they are works the eye wants to sink into.

But they also feel a bit antique, as if they were essentially charged and sumptuous late additions to Cubism. So it makes sense that at the same time he was doing them de Kooning was also seeing how far he could take his images of figures. Handling the face, however, remained an issue. He wanted the faces to be of a piece with the propulsive shapes forming the rest of the pictures, but the ones he drew, in literally matching those spiky forms, are corny and melodramatic.

In the Woman paintings from 1950 on, de Kooning found a solution. His route was to make the face slightly more satiric and absurd, and the idea gave his art a new kind of tension. In Woman I, the figure’s snarly, masklike head can feel like the natural climax of the thrashing brushwork evident everywhere else. But her grinning nightmare face is also like an impetuous and naughty, even vandalizing, afterthought, as if the artist were mocking himself, or saying that Abstract Expressionism itself could stand a deflating bit of graffiti drawn onto it.

So while the painting may attest to de Kooning’s mixed feelings about women, and may justify having been called misogynistic over the years, it has been tied together, as it were, with a needed and wonderful pinch of airy preposterousness. It presents an Expressionism, but one without the bitterness or doom so crucial to earlier European Expressionists such as Rouault or Beckmann. Like Guston’s images of his potato-head characters, who also have large, cartoonish eyes—in his 1973 Painting, Smoking, Eating, one of these characters is in bed, ruminating on paint cans, shoes, and French fries—de Kooning’s voracious ladies invite laughter. I laughed out loud when I discovered that in Woman with Bicycle our heroine has an identical second mouth, complete with gleaming teeth and lipsticked lips, set down around her neck.

The slapstick creations of de Kooning and Guston are not generally thought of together, and they were made many years apart. But pictures such as Woman I and Painting, Smoking, Eating, where comic-strip shortcuts seem to spring up out of rich painterly approaches, make one feel that Abstract Expressionism, in the efforts of these two artists, can be looked at a little differently. One can believe that part of its contribution is to have added a distinct note, at once frantic, earthy, and vaudevillian, to the history of representational painting.

De Kooning never again put so many aspects of himself into his work as he did in the Woman pictures. No other pictures give so strong a taste of his slyness, irreverence, and bite—the part of him capable of saying “In art one idea is as good as another.” Yet it is remarkable how, in his fifties, he was able to take off in so many new directions. Thrusting brushwork in itself, alternately scratchy, creamy, and feathery, seems to be the subject of largely abstract paintings from the Fifties such as Police Gazette and Gotham News. Exactly what such paintings are about is a mystery to me; but there is a gripping sense of purpose to the choppy flow of shapes and colors. More accessible are the equally abstract works, such as Merritt Parkway and Door to the River, which followed in the late Fifties and early Sixties. Looking at these nearly seven-foot-high canvases, with their few zones of resplendent blues, tans, and greens slashed here and there with single huge brushstrokes, we think we look at the triumphant marks of some gigantic Zorro of the brush.

In many if not most commentaries on the artist, de Kooning’s work after the Woman pictures is often described biographically, almost naturalistically. Where his earlier efforts are seen and felt as being about his changing ideas about expression and form, and don’t involve us much with the man himself, the later pictures seem to call out most as images about his biography—where he lived, where he went. For viewers over the years, the very substance of these works, I suspect, derives in part from their terrific titles (which de Kooning didn’t always pick himself but which he obviously more than merely countenanced).

The titles Police Gazette and Gotham News, which accompany images of restless, churning painterly energy, conjure up a dynamic and romantically dangerous New York, while the titles Merritt Parkway, Suburb in Havana, Montauk Highway, Ruth’s Zowie, and Door to the River, which accompany more expansive, even imperial, images, together suggest city life being left behind on a drive to Connecticut or on a hop down to Batista-era Cuba, some of it perhaps in the company of Ruth (who was Ruth Kligman, a girlfriend at the time), with an end point being a view beyond the city altogether. The string of titles alone suggests the burgeoning of de Kooning’s existence and even of the New York art world.

De Kooning’s art from the 1960s on, perhaps mirroring his new, more isolated life in the country, became increasingly sweet-tempered and mild—and also, in the many works where the figure is clearly visible, more overtly comic and sexual. In paintings, masterfully scrawly charcoal drawings, and a small number of charming bronze sculptures, we see a kind of figure that is the antithesis of the militant creatures he drew right up through the time of Woman I. Boneless and goosey, his new figures seem capable at most of waddling. In paintings full of pinks, rose-reds, and whitened yellows, women stand before us or look like they have been pinned to a wall, their long dangling legs ending in high heels. More often they are on their backs, their legs spread open, and we look right down on them.

In these pictures de Kooning’s approach is often so splotchy, vaporous, or runny, or sometimes his units of color are so anarchically arrayed, that we wonder at times how he was able to move around any of the components that form the given painting. There hardly seems to be any structure there at all. Yet in time we see a bit of a grinning face, a hand, or even—as in some of the pictures in a lovely show of this work held this past spring at the Pace Gallery—an ankle and loafers. Then suddenly the image seems to focus. Although it is not necessarily what the artist was after, our enjoyment comes in good part from finding something recognizable and seeing how far we can go with it.

The figure was de Kooning’s starting point in his pictures from the mid-Seventies, too, but it is increasingly hard to see. The art of roughly the last decade of his working life makes us think instead of landscapes or images of grasses in water, or simply circulating movement in itself. His approach became progressively leaner and more emptied out. In the end, his canvases show merely looping red, blue, and yellow lines set against white backgrounds. It is these paintings, for which de Kooning was in some instances helped by studio assistants, that have raised questions about how cognizant the artist, then perhaps already suffering from dementia, was of what was happening in the studio. Yet the pictures feel organically related to everything that preceded them. They resemble the late efforts of many artists in being essentially pared-down demonstrations of the artist’s sense of form.

The paintings made in 1975 and in 1977, though, go deeper than that. In works where sometimes languorous and sometimes industriously patchy lines and shapes move in and around each other, and his paint surfaces are as sloshily wet-looking as he had ever made them, de Kooning could almost be portraying the relativism that underlay his art. One of the pictures is entitled …Whose Name Was Writ in Water, the words coming from the inscription Keats wrote for his tombstone. Keats may have been thinking about his not being remembered after his death. For de Kooning the words suggest more a self-portrait, as water, at least in the way it is about a state of endless shiftingness, might have been his ultimate subject.