Civilization was once a popular subject. Will and Ariel Durant’s The Story of Civilization, published between 1935 and 1975, told the history of the arts and sciences and the major events of political history from “Our Oriental Heritage” through “The Age of Napoleon.” Sir Kenneth Clark’s Civilisation was a memorable 1969 TV documentary, in thirteen parts, which guided viewers to monuments of art, architecture, and philosophy from the Dark Ages to the “heroic materialism” of the mid-twentieth century. Clark made a book out of the show, but the appeal of the series lay in the combination of spoken words and camera shots. It took as its unit of interpretation the career rather than the isolated deed, thought, or masterpiece. As a venture of high popularization, the series set a standard that the next generation has yet to meet.

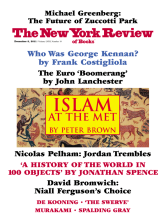

Niall Ferguson mentions Clark in his opening pages, and not without self-consciousness. Like Clark’s book, Civilization: The West and the Rest derives from the script of a documentary conceived for television; but where Clark confined himself mainly to the visual arts, Ferguson has aimed to cover a much wider field. The political, economic, military, and technological bases of civilization are his subject, including other civilizations besides that of the West. His disposition, however, toward the civilizations of China and Islam is indicated by his decision to call them “the rest.” Works of art make an early appearance but are soon given up.

Since Ferguson regrets what he calls the “de haut en bas” authority that Clark exemplified, he has taken precautions not to sound too high. He moves from artifact to structure to event, from king to president to imam, with a relentless horizontality. The book has a spiffy, jazzed-up, knowing air, which says to the reader: “You, too, can possess this kind of knowledge; you can make your own connections—the levers are in your grasp.” The tone is well adapted to the link culture of laptops and iPads, and it suits the message of the book: a dominant civilization must not hesitate to sing its own praises.

As his guide to the philosophy of history, Ferguson invokes R.G. Col- lingwood, the polymath philosopher and historian of early Britain. Collingwood in his Autobiography (1939) described the work of the historian as a reimagining of the mind of the past: “the re-enactment of a past thought.” The process could succeed only when one put a question to the partly resistant materials and had the patience to coax an answer in terms not wholly dictated by present concerns.

The further one reads in Ferguson’s book, the more incongruous this opening citation from Collingwood appears. Ferguson has not, in fact, launched his inquiry into the rise and fall of civilizations from an inward mastery of the named virtues or values of any particular civilization. Rather, his questions, and the answers that sometimes seem to hit before a question is asked, are dictated by habits, traits, and products of the very recent West, framed in an idiom strongly associated with American schools of management. The almost-personified West whose triumph he celebrates, and whose future he prognosticates, was shaped from the first, Ferguson wants us to believe, by six “killer apps”: elements comparable to the applications you download to enhance a smart phone.

The killer apps are “competition” (which, to make a proper “launch-pad” for states and economies, requires “a decentralization of both political and economic life”), “science,” “property” rights, “medicine,” “the consumer society,” and the “work ethic.” These make an absurd catalog. It is like saying that the ingredients of a statesman are an Oxford degree, principles, a beard, sociability, and ownership of a sports car. Ferguson’s killer apps of the West—both the idea and the phrase—in less than a decade will date the book as reliably as the adoption by a pop psychologist in 1966 of the word “groovy.”

If for several centuries, as Ferguson believes, the West has enjoyed an “edge” on the rest, what should we mean by the West? It is “much more than just a geographical expression”; one must think rather of “a set of norms, behaviours and institutions with borders that are blurred in the extreme.” A key word that occurs quite early is “dominance.” Ferguson locates the decision points or historical residues of dominance by writing about a landmark, crux, or monument (the author being filmed in the historically significant place). He backs his claim for its importance with statistics and charts, where relevant, and cuts to another comparable place or thing. In this presentation, pictures are all-important. Unhappily, in the book version we do not have the pictures. The added value may be that the book contains more words than the television series. Then again, a second drawback is that the words were punched in with images in mind. In a passage like the following, for example, the on-screen continuity is plainly meant to cut from the environs of the Yangzi River to the Thames:

Advertisement

The Black Death—the bubonic plague caused by the flea-borne bacterium Yersinia pestis, which reached England in 1349—had reduced London’s population to around 40,000, less than a tenth the size of Nanjing’s. Besides the plague, typhus, dysentery and smallpox were also rife.

Poor sanitation, Ferguson concludes, made London “a death-trap.” Two pages later comes a paragraph on Breughel’s Triumph of Death. The images may make all this vivid as the words do not.

A contrary-to-fact premise with which Ferguson occasionally teases us is that China could have dominated the West. Sanitation was on its side, and the place was full of inventions: “Chinese innovations include chemical insecticide, the fishing reel, matches, the magnetic compass, playing cards, the toothbrush and the wheelbarrow.” Great little things, and yet: “By comparison with the patchwork quilt of Europe, East Asia was—in political terms, at least—a vast monochrome blanket.” This was because it lacked the first killer app, “competition”: an active virtue that the West came to understand in the age of exploration. Early on, Ferguson sums up his conclusion in favor of the West: “As Confucius himself said: ‘A common man marvels at uncommon things. A wise man marvels at the commonplace.’ But there was too much that was commonplace in the way Ming China worked, and too little that was new.”

Evidence of Western ascendancy is made to issue from data of the most various kinds. For example: “The average height of English convicts in the eighteenth century was 5 feet 7 inches,” while “the average height of Japanese soldiers in the same period was just 5 feet 2½ inches.” So, “when East met West by that time, they could no longer look one another straight in the eye.”

This is a curious deduction from an unexpected comparison. Another sort of commentator might infer that the Japanese soldier, keeping guard on the English convict, would be compelled to learn a new dexterity in the martial arts: to swing his rifle butt upward, in a chopping motion, which would lead to the refinement of jujitsu—an art that cross-fertilized the Western mind after World War II. Ferguson ignores the eccentric invitations that lie in his path, and cannot be trusted to realize how an asset like height might be turned against the advantage of its owner.

The triad of goods familiar to Americans—life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness—appeared in Locke’s Second Treatise on Government as life, liberty, and property. Ferguson prefers the no-nonsense Lockean version, and says of the American Revolution: “At root, it was all about property.” At root, all about. This sort of locution pervades the book. Again: “In the end, of course, the anomaly of slavery in a supposedly free society could be resolved only by war.” Of course? The end might have been a long way off had Stephen Douglas won the election of 1860. At-root motivations and of-course developments and in-the-end inevitabilities suggest the grip of teleology: the turn of mind that tells us things had to come out the way they did because they were always leading to us, and how can we imagine “progress” toward something different from ourselves?

For all his jumps, Ferguson sticks to a largely familiar subject matter framed by conventional judgments. The American Revolution stands for true progress, and the French Revolution for counterfeit progress. The latter, he believes, put into practice the political philosophy of Rousseau: it went astray by a literal adoption of the doctrine of the general will. This discovery Ferguson credits to Edmund Burke, but the truth is that Burke wrote very little about Rousseau, and never commented on the doctrine of the general will. He criticized the cult of Rousseau among the revolutionists for nontheoretical reasons: because it was a cult, a mask for collective egotism.

In Reflections on the Revolution in France, Burke charged that the wildness of Jacobinism had a British rather than a French source. It came from the post-1688 development of the radicalism of natural rights. Though he does not cite the name, Burke certainly does mean Locke, among others. What was wrong with Locke, or with supposing that the Glorious Revolution really was a revolution? Burke thought British liberty a tradition that England and perhaps America were able to digest; but “the old Parisian ferocity” was too little practiced in the arts of self-restraint to be trusted with so volatile a mixture. This emphasis, if acknowledged, would spoil the simplicity of Ferguson’s reading—the good individualist Locke versus the bad collectivist Rousseau. But history comes out of just such accidents as violate our cherished allegories.

Advertisement

Finally, when Ferguson writes about “Rousseau’s pact between the noble savage and the General Will,” he can only mislead. There is no character called the “noble savage” in the writings of Rousseau; there is, rather, an image of man in a presocial state, which Rousseau invents to clarify his ideas of law and convention in the Discourse on Inequality; but the Discourse is a different book, which advances a separate argument from the Social Contract with its doctrine of the general will. The distortion here goes beyond the compression that is necessary in a work of popularization. It is a falsification of intellectual history.

No scholar looking in from outside would guess that the foregoing materials are all brought forward in a chapter on “Medicine.” The rest of the contents of that chapter give a fair suggestion of the capriciousness that the killer-app divisions have forced on this book. “Medicine” alone takes us past the eighteenth-century revolutions, through the Napoleonic Wars, to the French Empire with a passing remark on Indochina (since Ho Chi Minh was a follower of the French Revolution). Still tracking what he calls medicine, Ferguson recounts the numbers that perished by tropical diseases in French West Africa, and comes to a temporary point of rest at the German prison camp on Shark Island.

A section on the imperialist scramble for Africa leads, eventually, to a contrast between the numbers of West Africans who fought with France in World War I and the Indian soldiers who fought with the British. The mortality rate of British soldiers was twice that of British Indians. Of the French colonial soldiers, “one in five of those who joined up” died for France, says Ferguson, whereas “the comparable figure among French soldiers was less than 17 percent.” Reading this, one nods and sighs, but hang on: less than 17 percent is another way of saying sixteen-point-something, which means that roughly one in six French soldiers died in World War I. How stark a contrast does that make with the “one in five” French colonials who died?

The chapter on medicine runs fifty-five pages. It stands at the heart of the book, and it ends with these words: “By 1945, it was time for the West to lay down its arms and pick up its shopping bags—to take off its uniform and put on its blue jeans.” We are thus prepared for the chapter on consumption: “What is it about our [Western] clothes that other people seem unable to resist?” And it is here that the main lines of an overarching narrative can be felt to emerge. Ancient Chinese civilization and medieval Muslim civilization were ahead of the West but, lacking command of the killer apps, they were set back almost permanently. Yet luxury, inattention, and a fatal indifference to the depth of our own resources have marred the vitality of the West. China will win, if it does win, by having successfully copied the North Atlantic commercial democracies; also, because plenty of Protestant missionaries went there to plant seeds of competition, science, and work.

The third “rival” among the civilizations, Islam, in Ferguson’s view is not an active and energetic civilization at all, but a “cult of submission” whose only imaginable influence is destructive. A consolation for the West may be drawn from the fact that we have been through all this before. The Japanese were emulators of Western consumption at the start of the twentieth century, just as the Chinese seem to be at the start of the twenty-first. “Unsure,” says Ferguson, about the secret of Western power, “the Japanese decided to take no chances. They copied everything.” Constitutions, economies, military drills, school systems, and most revealing of all: “The Japanese even started eating beef.” The humor of the book sits uncertainly on the page; but this detail may go well with a hearty delivery and pictures of beef.

Still, in whatever medium, Ferguson is limited by his choice of the gimmick of killer apps. Having resolved to speak about much of the twentieth-century as a history of “consumption,” with a subplot on the export of textiles from West to East, he cannot resist the temptation to treat the rise of fascism as a matter chiefly of clothes:

With the exception of Mussolini, who wore a three-piece suit with a winged collar and spats, most of those who participated in the publicity stunt that was the March on Rome were in makeshift uniforms composed of black shirts, jodhpurs and knee-high leather riding boots.

Six pages later, the textile and political themes must somehow be brought together, in World War II, so we get a paragraph beginning with the wide-eyed sentence: “Everyone, it seemed, was in uniform.” (Montage over military music: khakis, blackshirts, navy whites, a line of paratroopers ready to jump.) Near the close of the chapter, Ferguson avows his belief that the atomic bomb was “one of the greatest creations of Western civilization”; for, whatever one might say about Hiroshima and Nagasaki, “the Bomb’s net effect was to reduce the scale and destructiveness of war, beginning by averting the need for a bloody amphibious invasion of Japan.”

The last sentence comes from justifications of the dropping of the bomb offered by Truman and Churchill. Among those who disagreed, in August 1945 or later, were Generals Eisenhower and MacArthur, and Admirals Nimitz and Leahy. General Curtis LeMay, who commanded the American firebombing of Tokyo and other Japanese cities, estimated that even without the atom bomb the war would have ended in September 1945. Why does Ferguson turn the self-justification of a nation at war into a fact about the history of civilization? Somewhere close to the heart of his purpose is the felt need to confer on the triumph of the West an air of inevitability, and also a clear conscience.

A long, ambitious, partly speculative chapter on “work” examines the thesis of Max Weber in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Was there a strong correlation between Protestant asceticism and what we now call the “work ethic”? Ferguson, for reasons that are obscure, treats Weber and his argument with a shade of contempt. Yet he agrees with Weber, lodging only one major reservation: that the thesis underrated the civilizing influence of Christianity itself. The chapter closes with miscellaneous reflections and charts about the comparative rates of churchgoing in Europe and America. The sources of American “dominance,” thinks Ferguson, have something to do with regularity of Christian observance. Chesterton, Waugh, and C.S. Lewis are quoted here; they were on to something about God and the Americans get it, while Europe, idle and dissolute, is now a vanquished supremacy.

But merely to recite the conclusion is not to convey the flavor of an extraordinary extended passage. One paragraph on “work” begins with the coat-trailing question “Who killed Christianity in Europe, if not John Lennon?” and ends with another question: “Was the murderer of Europe’s Protestant work ethic none other than Sigmund Freud?” The train of association that places John Lennon in the first sentence may elude even a close reader of Ferguson; the meaning of the reference to Freud becomes clearer in the paragraphs that follow. Ferguson has in mind The Future of an Illusion, where Freud analyzed all religion as a form of neurotic dependency that condemns mankind to perpetual immaturity.

Is it true that Freud “set out to refute Weber”? The reader may suppose that Freud had read with care and argued against Weber’s theory; but Weber’s theory is never mentioned in The Future of an Illusion; indeed, there is not one entry under Weber in the index to the twenty-four volumes of the Standard Edition of Freud’s writings. The false hint planted by the phrase “set out to refute” turns out to be only Ferguson’s way of dramatizing a belief that grips him: Weber made allowance for the good that might come from nonrational motives, while Freud, in his treatment of religion, failed to do so.

There follows a celebration of American dominance and churchgoing. Here, finally, the book spins out of control. How many churches are in Springfield, Missouri? Well, it is “the town they call the ‘Queen of the Ozarks’ and the birthplace of the inter-war highway between Chicago and California, immortalized in Bobby Troup’s 1946 song, ‘(Get Your Kicks on) Route 66.'” Picture this:

There are 122 Baptist churches, thirty-six Methodist chapels, twenty-five Churches of Christ and fifteen Churches of God—in all, some 400 Christian places of worship. Now it’s not your kicks you get on Route 66; it’s your crucifix.

The argument here—that the vitality of a civilization may be measured by the number of well-attended churches—is not new; though nothing in the preceding 273 pages has quite prepared for this rhapsody. But there is something odd about the smart-aleck riff at the end. “Now it’s not your kicks you get on Route 66; it’s your crucifix.” That verbal jiggle-and-stomp would not be conceivable by a person with an ounce of real piety. If Ferguson has any idea what actually happens in the wide range of churches he mentions, there is no sign of it in these comments. One is led to conclude that he is a detached and vicarious proselytizer. He is praising religion from a place outside religion. And he aims to encourage Christian belief only in the broadest sense: a sense so broad that it includes Jews (though not Muslims or Hindus). Christian belief is a good thing, more vital to civilization than we ever realized, but it is good for them.

The kicks and crucifix have been forgotten just a page later, in a comforting haze of commercial uplift. And commerce does matter to Ferguson. The good thing about “competition between sects in a free religious market,” he says, is that it “encourages innovations designed to make the experience of worship and Church membership more fulfilling.” The appeal to the free religious market radiates a spirit of unity. He is describing the cement that binds the altars and the stock markets of the West.

Why then does the book close on a note of lament? “Not only are the churches of Europe empty,” but, says Ferguson, we have lost confidence in the value of our civilizing inheritance:

We also seem to doubt the value of much of what developed in Europe after the Reformation. Capitalist competition has been disgraced by the recent financial crisis and the rampant greed of the bankers. Science is studied by too few of our children at school and university. Private property rights are repeatedly violated by governments that seem to have an insatiable appetite for taxing our incomes and our wealth and wasting a large portion of the proceeds. Empire has become a dirty word, despite the benefits conferred on the world by the European imperialists. All we risk being left with are a vacuous consumer society and a culture of relativism.

Two pages later, Ferguson ushers in the furies who will dine on our self-neglect: al-Qaeda and the Muslim Brotherhood.

Civilization: The West and the Rest is a rich, undercooked, and finally inedible gumbo. Almost any name is apt to be found floating in it somewhere—Mozart, Polybius, Lincoln, Atatürk, Breughel, Thomas Cole, Adam Smith (Smith a little more than the others). And yet, after several hours spent with Ferguson and his killer apps, one may be uncertain what his definition of civilization is. To judge by the contents of the book and its intermittent approaches to argument, the answer runs somewhat as follows. Civilization is a system of financial profit, founded on self-discipline, some of whose opulence goes to support the arts. Its desired effect is to render human life more comfortable and more complicated, but not too soft. This end civilization achieves by affording political and economic support to the exertions of individual genius. It sustains itself by a regime of liberal and scientific education, whose highest achievements are modern medicine, advanced weaponry, and communications technology. The final reward of a consummated civilization is to have persuaded a billion or more persons, on more than one continent, to see it as it sees itself and to have pushed to the side and uprooted less competitive ways of life.

Niall Ferguson is a patriot of the West. He aspires to be a calmer and a more reflective writer than he is. That has to be the meaning of his (evidently sincere) invocation of R.G. Collingwood in the opening pages. He cherishes a desire to become a historian of the virtues of the West, and he has some of the necessary equipment: he is a quick study, endlessly resourceful with lists, numbers, and juxtapositions. But he lacks patience. He wants to arrive at a formula, a master clue, a quotable phrase, and to get there fast.

In the present book, he has also partly concealed a passion that played a large role in guiding him to the study of history: admiration for the achievements of British imperialism. He was less reluctant to mention this motive in some of his previous writings. In an essay in The New York Times Magazine on April 27, 2003, on the heels of the American conquest of Baghdad, he declared himself “a fully paid-up member of the neoimperialist gang,” and said of the antecedents of the Iraq war:

The reality is that the British were significantly more successful at establishing market economies, the rule of law and the transition to representative government than the majority of postcolonial governments have been.

Perhaps because he is writing for an international audience, or because of the less vibrant condition of the American empire in Asia today, he confines his shows of sentiment in Civilization to a few digressions and muttered asides.

A partial exception is the thirty-page conclusion, appended to his final chapter on the killer apps. Here Ferguson attempts to judge the contest of the current imperial “rivals,” and he finds comfort in the thought that a deep and immitigable “clash of civilizations” has not yet occurred. Of the main contenders—the West, China, and Islam—he lays odds on China while striking the attitude of a disappointed lover of the West.

What is missing in this coda, and missing throughout the book, is an awareness of a sense of “civilization” that mattered to John Ruskin, the teacher of Collingwood. It meant to Ruskin a pattern of duties and manners whose performance was scarcely conscious. It fostered habits of gentleness and obedience, as well as command, without a thought of profit or reward. It imparted a reverence for the good as a thing apart from cash value. This perspective is bound to be lost if one thinks of civilizations by race, region, and religion. It is doubly lost if one goes over the strategies of winning teams in the past in order to prognosticate the scramble for continents in the future.